In 1916, an unassuming nightclub by the name of Cabaret Voltaire opened in the heart of Zurich's old town. An artistic oasis in war-torn Europe, the club came to embody a new age of freewheeling creativity. Described as a 'total pandemonium', it was here where the nonsensical movement known as Dada emerged. The spirit of Dada gave rise to the unconventional work of Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889–1943), the subject of a major retrospective currently at Tate Modern.

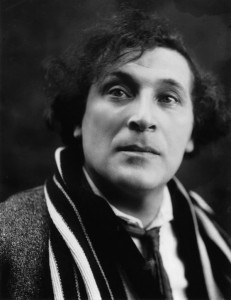

Sophie Taeuber with her Dada head

1920, gelatin silver print on card by Nicolai Aluf

An 'anti-art' and 'anti-bourgeois' movement, Dada was a reaction to – and rebellion against – the devastating impact of the First World War. The incomprehensible and illogical nature of Dada mirrored the absurdity of war, which encompassed the bohemian artists who had found refuge in neutral Switzerland. As Hugo Ball, the founder of the club, wrote 'Switzerland is a birdcage, surrounded by roaring lions.'

Starting with her involvement in Zurich Dada, the retrospective at Tate Modern traces the versatile practice of Taeuber-Arp leading up to her tragic and untimely death by accidental carbon monoxide poisoning in 1943. Organised in collaboration with Kunstmuseum Basel and MoMA, New York, the show assembles her wide-ranging body of work: abstract painting, costume design, embroidery, furniture, sculpture, illustration, photography, dance and performance.

An eclectic assortment of mediums, the one constant of her career – across many geographical locations and decades – was a sense of dynamism, accompanied by vibrant colour arrangements and geometric forms.

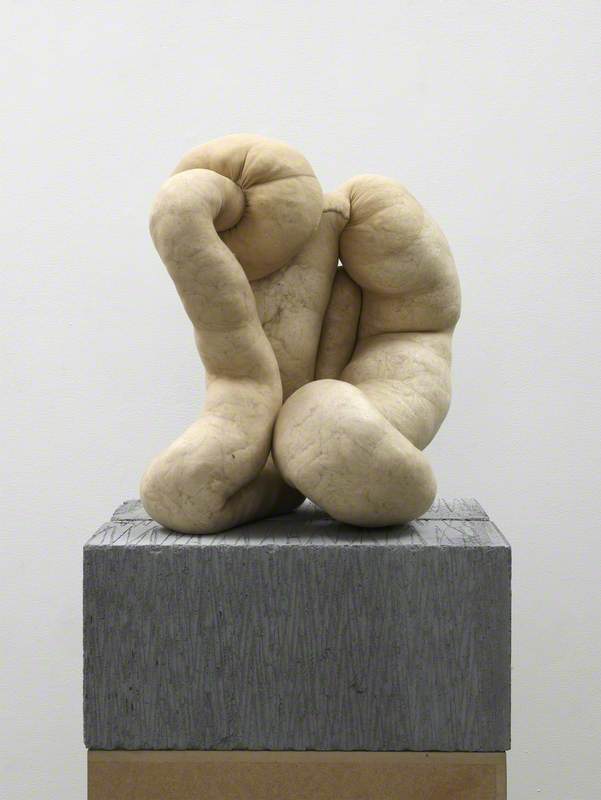

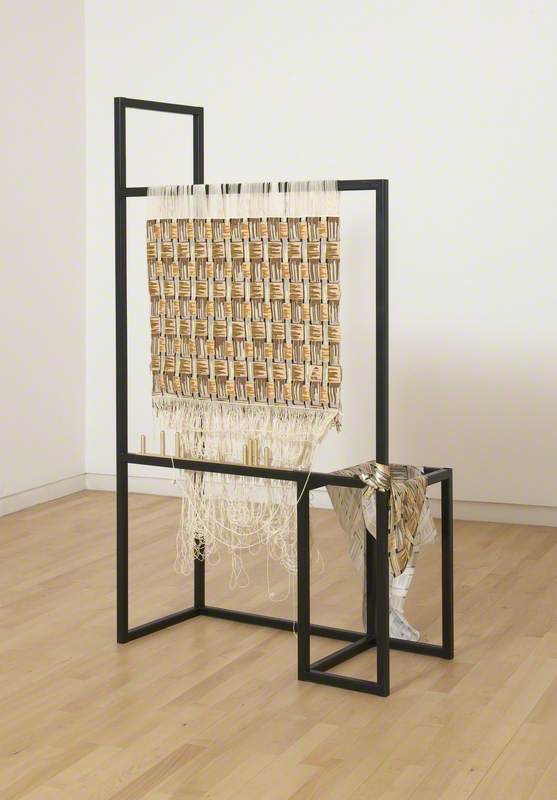

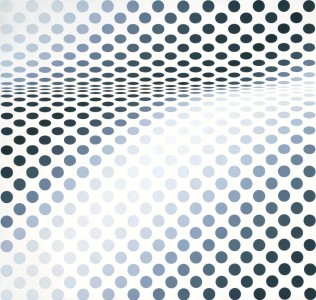

Embroidery

c.1920, wool on canvas by Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889–1943)

Born to a middle-class Prussian family, Sophie Henriette Gertrude Taeuber was the daughter of Emil Taeuber, a pharmacist who died when she was a child. To support the family her mother, Sophie Taeuber-Krüi, opened a bed and breakfast in Trogen, Switzerland. An embroiderer, Sophie introduced her daughter to the world of arts and crafts.

Between 1908 and 1910, Taeuber-Arp studied textile design at the School of Applied Arts in Saint Gallen, Switzerland, before heading to Munich to study textile design, weaving and beadwork. In 1912, she transferred to the School of Applied Arts in Hamburg, but was refused entry to Hans Heller's interior design class – 'I was disappointed that the instructor from whom I was so eager to learn furniture design would not have any women in his class.'

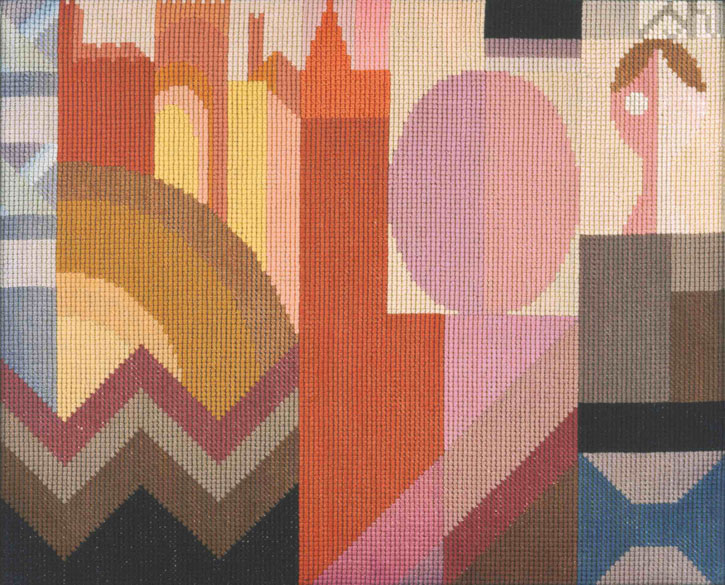

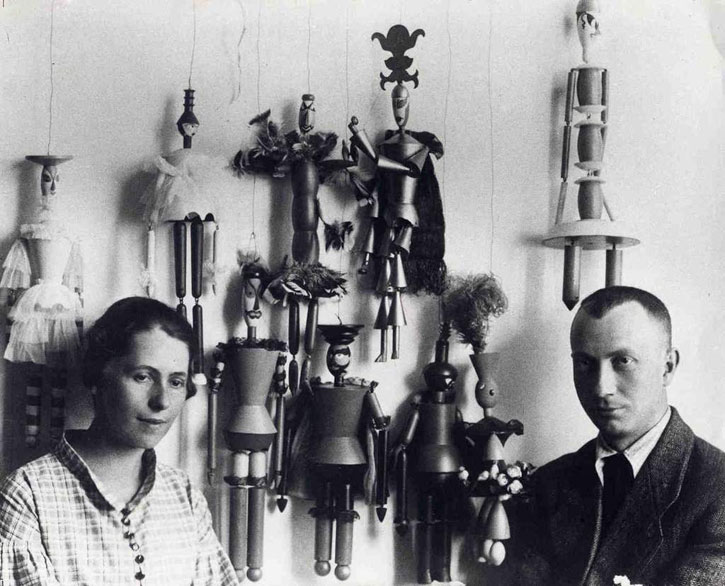

Sophie Taeuber-Arp and her sister Erika Taeuber

1921–1922 & 1916, photograph by unknown artist

At the outbreak of war, Taeuber-Arp returned to Zurich, where her paintings and sculpture reflected the radical abstraction inspired by the recent development of Cubism. She also trained with the pioneer of modern dance, Rudolf von Laban. A photograph from 1916 reveals Taeuber-Arp dancing at Cabaret Voltaire, wearing a striking Cubo-Dadaist-inspired costume reminiscent of mechanical, robotic forms.

At an exhibition in 1915 she met her future husband, the artist and poet Jean 'Hans' Arp who had escaped to neutral Switzerland to avoid conscription. Arp had briefly worked with Wassily Kandinsky and Der Bleue Reiter, and had mixed with avant-garde figures such as Pablo Picasso and Robert and Sonia Delaunay, the latter of whom became a close friend of Taeuber-Arp's. Hans also performed at Cabaret Voltaire, offering live poetry readings.

While their romantic relationship developed, Sophie and Hans collaborated artistically, finding a common creative ground that turned away from representational forms and artistic convention. The couple were married in 1922 and adhering to Swiss custom, Sophie's name changed to 'Arp-Taeuber', though by the 1930s her professional name switched to 'Taeuber-Arp'.

Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Ascona, 1925

Like many other women artists married to well-known male artists, Taeuber-Arp's legacy suffered, in the sense that her career was eclipsed by her husband's. Especially after her death, Taeuber-Arp faded into obscurity while Arp's fame swelled; he exhibited at major retrospectives internationally and received the Grand Prize for sculpture at the Venice Biennale in 1954.

During Taeuber-Arp's lifetime she exhibited work in group shows, but never held a solo exhibition. Yet evidence suggests that the couple avoided rivalry, with Hans often pushing to have Sophie included in exhibitions that only he had been invited to participate in.

According to Renée Riese Hubert, the couple 'implicitly looked upon the other simultaneously as a disciple and a guide, even when the two worked on the same project. They related to one another alternatively as a producer and as critic, as performer and as spectator…'

Keeping within the utopian aims of Dada, which sought to eradicate the notion of the venerated individual artist, the couple worked towards a communal work of art. While Taeuber-Arp did achieve great success during her lifetime, ultimately it was Hans, who enjoyed greater freedom and success.

Installation shot of Sophie Taeuber-Arp at Tate Modern, 2021

Five years after Taeuber-Arp's death, Hans created her catalogue raisonée and later organised the first retrospective of her work at the Kunstmuseum Bern in 1954. Yet as the MoMA exhibition catalogue explains, while Hans' catalogue was 'a well-intentioned attempt to consolidate her reputation', it ultimately excluded much of her multifaceted applied arts practice. For this reason, the Tate show acts as a corrective moment in art history: it shines a light on her design and craft production that was previously dismissed as 'minor' art.

It was also Taeuber-Arp's commitment to applied arts and design that prevented her from being regarded as a protagonist in any particular modern movement, many of which upheld abstract painting above all other mediums. She actively used writing to promote the applied arts, publishing the text 'Remarks on the Instruction of Ornamental Design' in 1922, and later co-wrote Guidelines for Drawing Instruction in the Textile Professions in 1927.

Installation shot of 'Sophie Taeuber-Arp' at Tate Modern, 2021

In 1918 she developed five marionettes for the puppet play King Stag at the Swiss Marionette Theater, which explored the theme of psychoanalysis. The tongue-in-cheek names of two of her marionettes reflect her humour, one figure is called 'Dr Oedipus Complex', another 'Freudanalytics'. Anticipating the interests of the Surrealists in the 1920s and 1930s, psychoanalysis greatly interested Taeuber-Arp, whose sister had received analysis by Carl Jung and co-founded the Zurich Psychological Club.

King Stag closed prematurely due to complaints from the audience and the arrival of the Spanish flu. Although the Zurich audience was sceptical of her daring, modernist vision, the marionettes were revered when published in Dada's Der Zeltweg. In 1922, Vanity Fair wrote that Taeuber-Arp's 'revolutionary' puppets had 'caused a real sensation'.

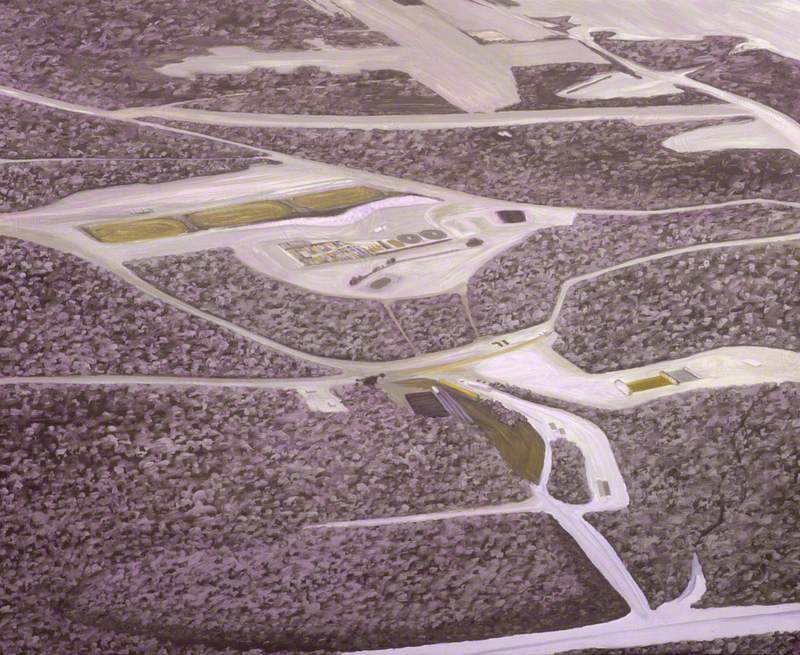

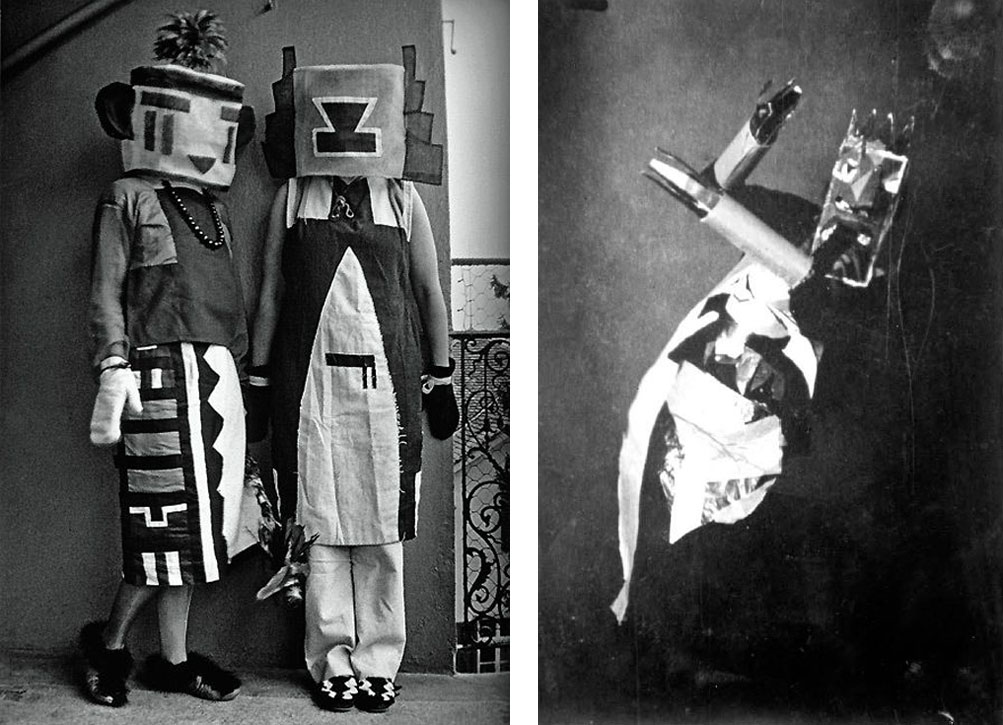

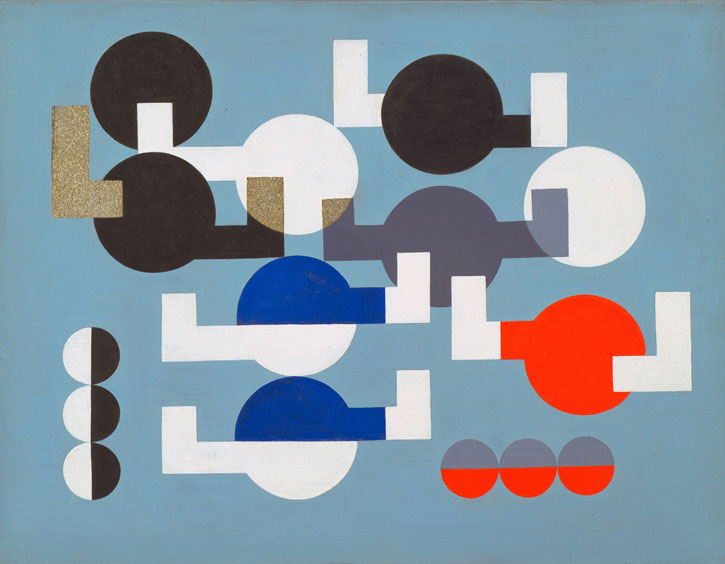

Composition of Circles and Overlapping Angles

1930, oil on canvas by Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889–1943)

The influence of Taeuber-Arp's training in expressionist dance remained intrinsic to her abstract aesthetic. Referring to Hugo Ball's description of her dance that 'every gesture is ordered in a hundred parts, sharp, light, pointed', Arp later reflected that: 'what Hugo Ball wrote about Sophie Taeuber's dance could be repeated with respect to the marionettes she produced at this time.' In the catalogue raisonnée of 1948, Hugo Weber described her as the 'artist of the circle… whose paintings brought corporeality and choreography together.'

In the late 1920s, the couple moved to France after being granted French citizenship, and in 1929, Taeuber-Arp gave up her teaching position in Zurich. She received a number of lucrative commissions, including a major project for the Strasbourg entertainment complex known as the Aubette, for which she was invited to redesign the walls and ceilings of the tearoom and bar. The payment for this commission allowed the couple to design their live-in studio in Clamart, in the outskirts of Paris, which had been designed by Taeuber-Arp herself.

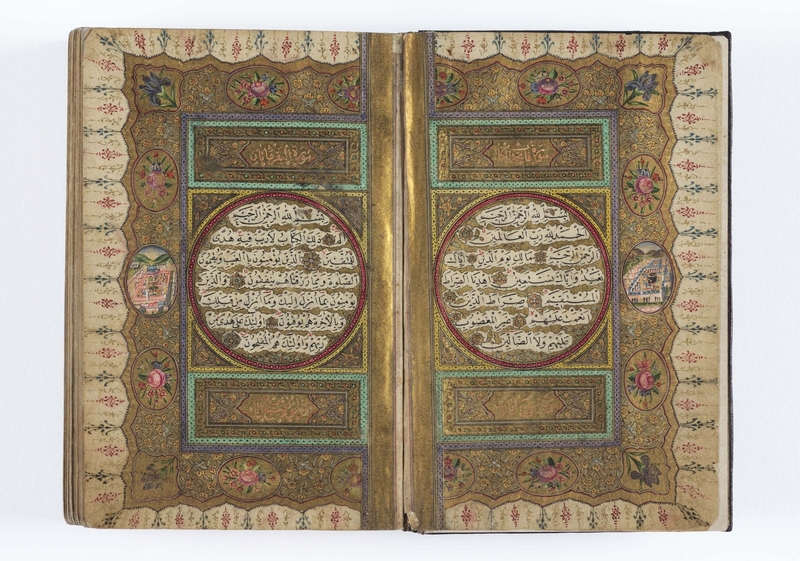

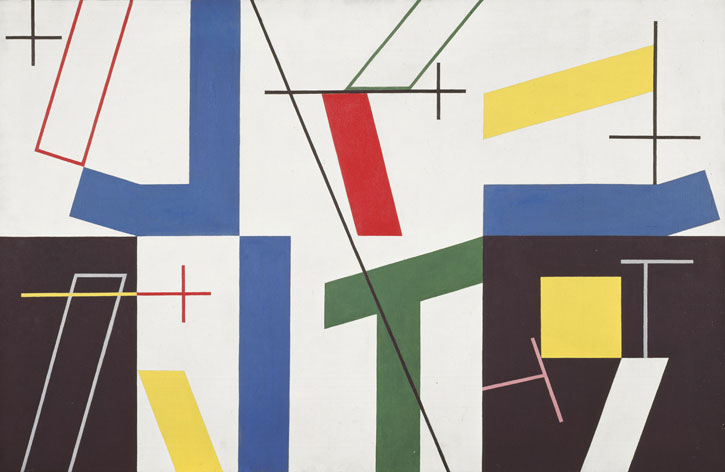

Six Spaces with Four Small Crosses

1932, oil paint & graphite on canvas by Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889–1943)

Throughout the 1920s, due to the increased exhibition of her textile and design work – including jewellery, stained-glass, cushions, furniture and interior design – Taeuber-Arp was seen as a designer rather than as a fine artist. But throughout this time she continued to paint, experimenting with photography, dance and edited an art journal. Her works on paper and paintings continued to reflect her engagement with abstraction and the aims of the Constructivists, as seen in paintings such as Six Spaces with Four Small Crosses (1932).

By June 1940, as the German army advanced into Paris, Sophie and Hans fled Clamart, moving to various locations across France before returning to Switzerland in 1942. Not long before, Taeuber-Arp had produced one of her most charming works on paper Geometric and Undulating (1941), which is included in the Tate show.

In 1943, at the age of 54, Taeuber-Arp died of an accidental carbon-monoxide leak. She had missed the last tram home the night before and slept in a summer house with a faulty stove.

In the decades following her death, her crafts-based practice faded from view, though Arp's catalogue raisonée preserved the memory of her paintings (around 600 oil paintings came to light after her death).

Today, we are able to appreciate the full extent of Taeuber-Arp's desire for an authentic vision, which blurred the boundaries between art and life. In 1922 she said: 'Only when we go into ourselves and attempt to be entirely true to ourselves will we succeed in making things of value, living things, and in this way, help to develop a new style that is fitting for us.'

We are left wondering what could have been achieved had both she, and her works, continued living with rhythmic vitality.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK