Despite the often-bright sun of the past few months, the darkness of uncertainty and loneliness, and the claustrophobia of isolation are never too far away. Who better, then, to document this cheerful mood than some of the most upbeat of the Scandinavian artists?

From Vilhelm Hammershøi's empty rooms to the stormy seascapes of Peder Balke, here are six Scandinavian* painters who captured the essence of what it means to be truly, artistically, miserable.

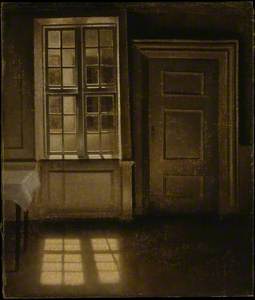

Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916)

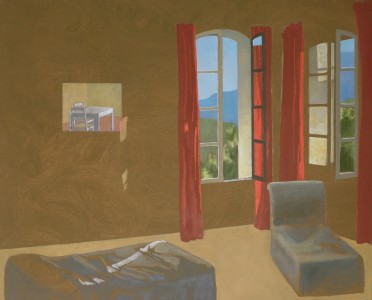

Frequently compared to Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) and inspired by seventeenth-century Dutch realism and James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), Vilhelm Hammershøi's paintings have a quiet, clean beauty that is rendered in muted but glowing colours. The majority depict his two apartments in Copenhagen, with an intensity that many of us will now recognise after over three months indoors. The motif of the window is repeated throughout his pieces, lending a sense of transience and mutability.

Hammershøi painted all over Europe, but found his aesthetic peak in London, where the atmospheric smog was a great inspiration. His nadir was Paris, where his work became too detailed.

Famously, the celebrated writer Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) saw Hammershøi's portrait of his fiancée and travelled to Copenhagen to write a book about the artist, before finding him too dull to put into words.

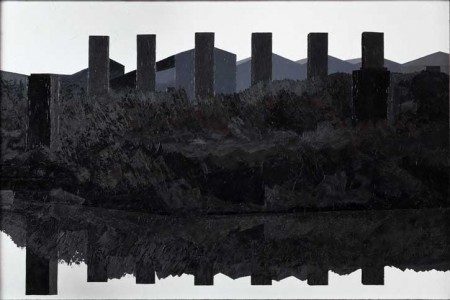

Peder Balke (1804–1887)

In contrast to the peace of Hammershøi's works, Peder Balke's landscapes are overhung by looming storm clouds, with rolling waves in the foreground. He depicted the great contrast in nature between light and dark, and between the elements. There is a sense of the impending threat of the natural world, but also the strength of light issuing from behind the clouds.

Balke's paintings are of the far north of his native Norway, the North Cape in particular. His early education was funded by farmers in his area, for whom he painted in return. Balke was also committed to social justice, turning to this when his career failed. He purchased farmland in order to provide a suburb for workers to live in, lending money himself for them to build.

In his works, one can see the inspiration of Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), a friend of his teacher Johan Christian Clausen Dahl (1788–1857). His depiction of Norway was in line with contemporaneous attempts to capture what was unique and precious about a painter's native country.

Laurits Andersen Ring (1854–1933)

In contrast to Munch's interior struggles, Laurits Andersen Ring looked outwards, at the hardship of life – particularly rural life – in his native Denmark. Ring's connection to the countryside is epitomised by his last name, which he took from his native village. He was a social revolutionary, who was prepared to level arms against his government in his youth, as a member of the 'Rifle movement' of students.

Ring's pieces often show the subject at the edge of something, in a doorway or at a railway crossing, for example. This state of transience has been variously theorised as the representation of the thin membrane separating life and death, or between tradition and modernity.

Road in the Village of Baldersbrønde (Winter Day)

1912

Laurits Andersen Ring (1854–1933)

His pieces are grounded in the social realism that comes from the depiction of the austerity and difficulty of contemporaneous rural life, but are often tempered by Symbolist motifs, small keys to deeper meaning within the painting. These create a further tension between interior and exterior.

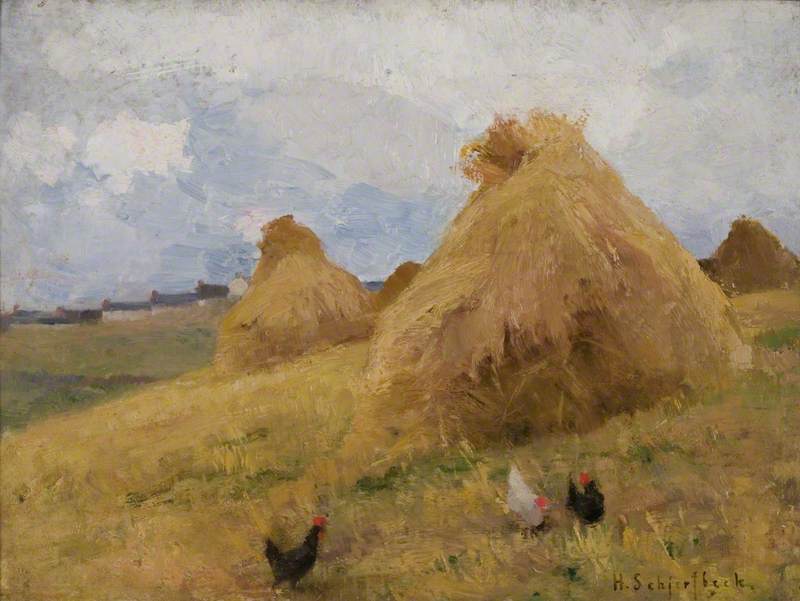

Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946)

Finnish artist Helene Schjerfbeck, despite being well known domestically, has only recently been celebrated in Britain, with a large retrospective at the Royal Academy in 2019. Her painting style changed through her life, but it is her portraits which stand out, with their unique treatment of colour and shape. Like Munch, she was affected by childhood illness, as she broke her hip falling downstairs aged four. Her limp was reportedly the reason that her engagement to a mysterious 'Englishman' was broken off, as his parents thought her hip was tubercular.

The Convalescent

1888, oil on canvas by Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946)

Schjerfbeck travelled across Europe, painting her surroundings, and her self portraits. When she painted others, it was always people that she knew. The simplicity of her later style belies the complex portrayal of her subjects, capturing a rich inner life.

Perhaps less gloomy is the only work of hers in a UK public collection, Chickens amongst Cornstooks, painted in St Ives in around 1888.

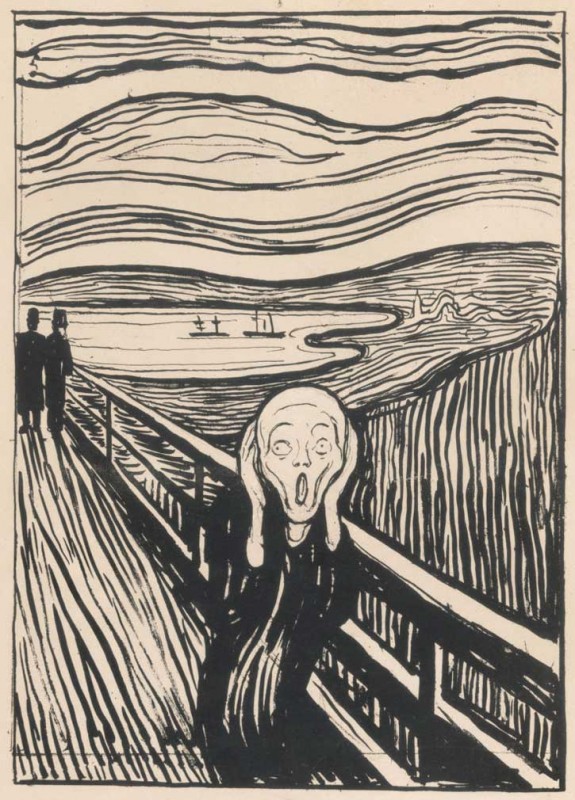

Edvard Munch (1863–1944)

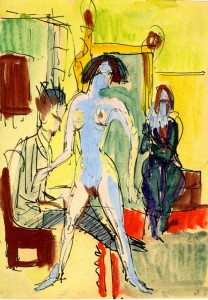

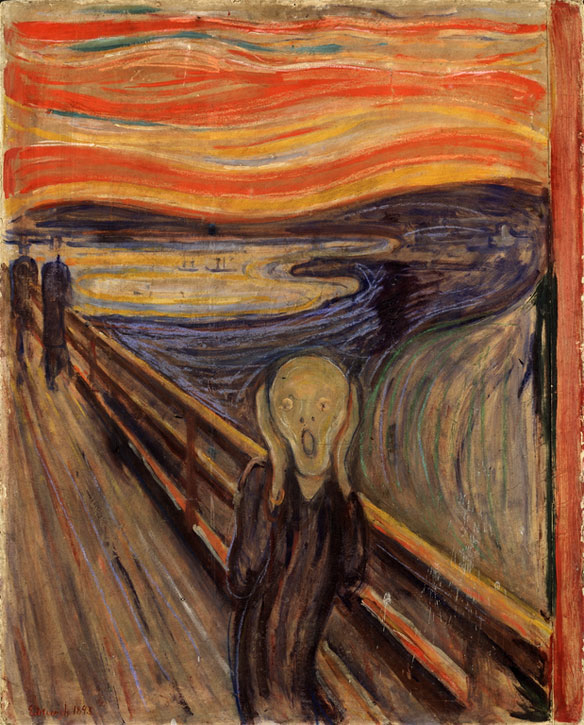

Probably the most well-known of these artists, in particular for the very memorable picture The Scream, Edvard Munch translated his troubled inner state into Expressionistic paint.

The Scream

1893, oil, tempera & pastel on cardboard by Edvard Munch (1863–1944)

As a child, Munch was sickly and often confined to bed. However, he was able to use art as an expression of the world from which he was cut off. Later, despite studying in Norway's best art school, he preferred to paint en plein air – perhaps realising the value of being able to work outside after a long isolation indoors. However, in a move away from Realism, Munch's work was always tied to the interiority of Symbolism, which sought to depict ideas or emotions, a mental state rather than a concrete reality.

Munch's life was marked by loss and illness. His painting, The Sick Child, drew on the death of his sister, who died when he was 14. He also struggled with romantic relationships, always feeling that art was more important. These experiences, together with his alcoholism, helped to create the tortured atmosphere of much of his work, particularly the pieces that he made in Berlin at the turn of the twentieth century. His style changed over the years, but never lost the wild intensity that saw him paint his most famous pieces.

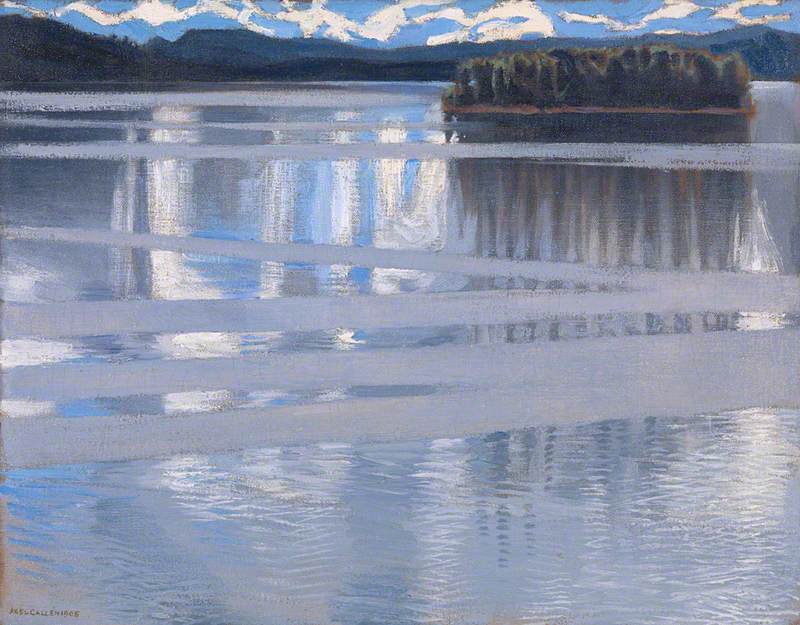

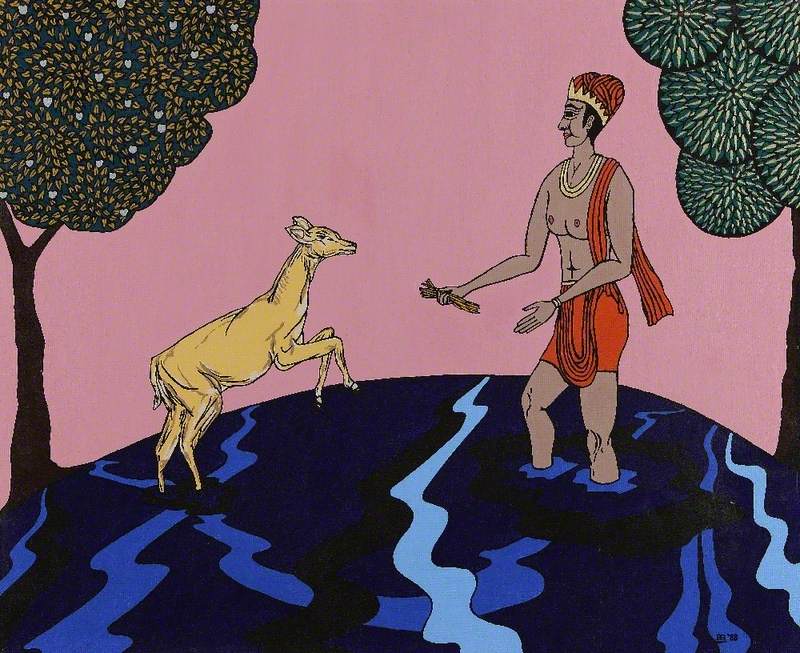

Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865–1931)

Returning to the countryside, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, like Ring, changed his name in order to demonstrate his connection to the land. In Gallen-Kallela's case, his name change was a popular contemporary expression of the rejection of his Swedish name (Gallén) and the adoption of a name that expressed his Finnish heritage.

Kullervo Herding his Wild Flocks

1917, watercolour by Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865–1931)

Gallen-Kallela's ties to his land were even deeper – he illustrated Kalevala (Land of Heroes), the Finnish epic, which was key to the development of Finnish national identity and eventual secession of Finland from Russia in 1917. He even fought in the Finnish Civil War in the following year. Like many of these artists, however, he worked across Europe, even installing his works alongside those of Munch in Berlin, adopting some of the Symbolist style thereafter. Travelling further afield, Gallen-Kallela painted in Kenya and the Americas.

Although his works are somewhat more cheerful than many in this list, they capture the empty vastness of Finland's north, of light on snow.

India Lewis, writer and co-founder of @radicalwomenshistory

* Note: we are using Scandinavian in the common English usage to include the Nordic country of Finland as well as Norway, Sweden and Denmark