In 1949, the Scottish painter Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004) visited the Grindelwald glaciers in Switzerland with some friends. As they picked their way across the frozen sea of ice and rock, she was overwhelmed by the experience:

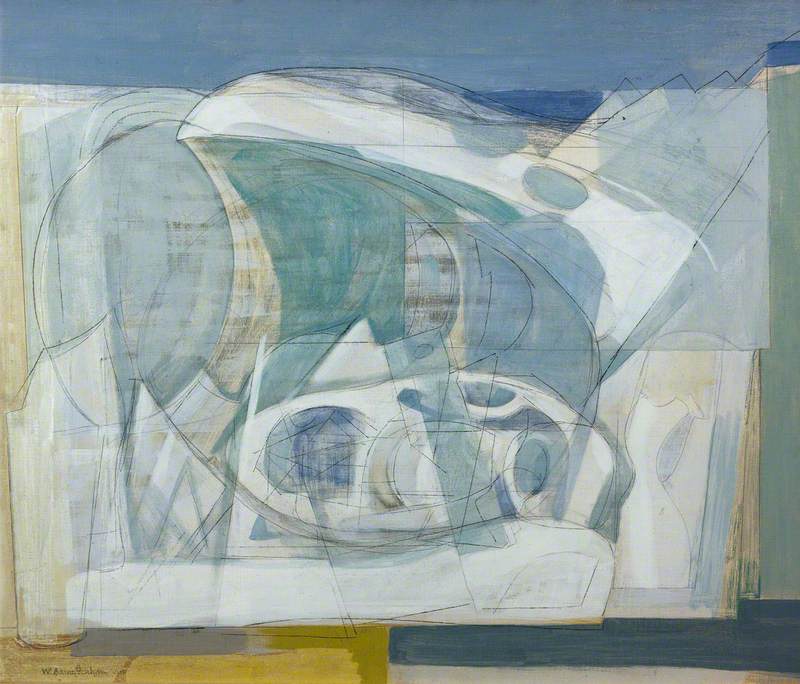

'[The] massive strength and size of the glaciers, the fantastic shapes, the contrast of solidity and transparency, the many reflected colours in strong light, the warmth of the sun melting and changing the forms, in a few days a thinness could become a hole … a piece could disintegrate and fall off, breaking the silence with a sharp crack and its echoes. It seemed to Breathe!'

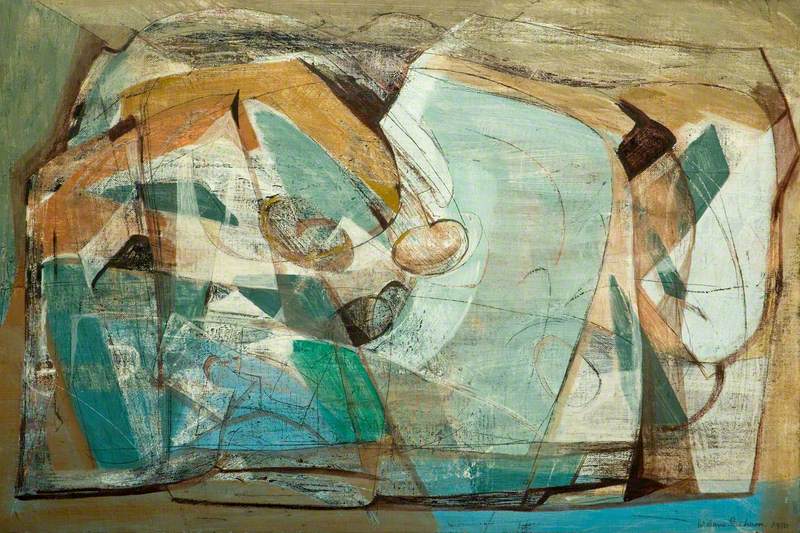

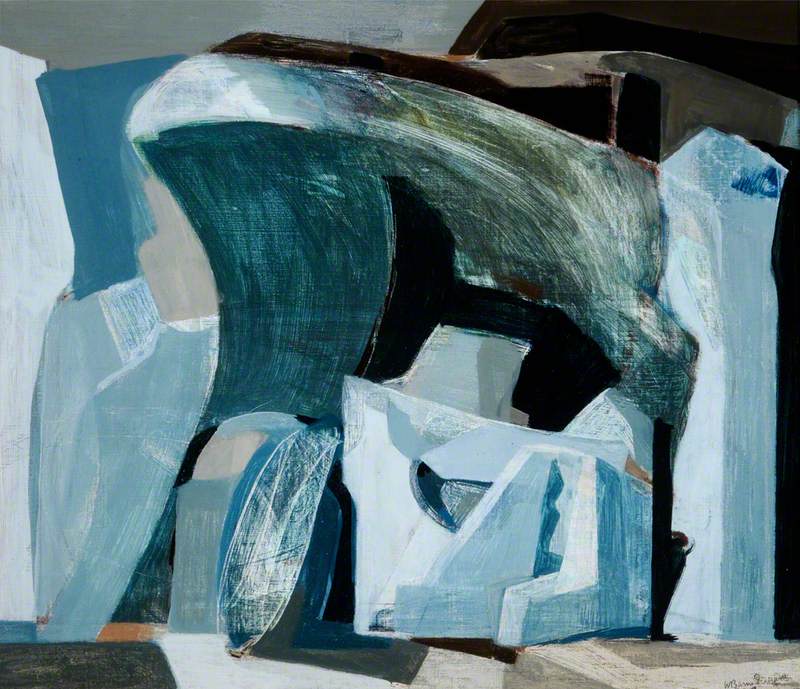

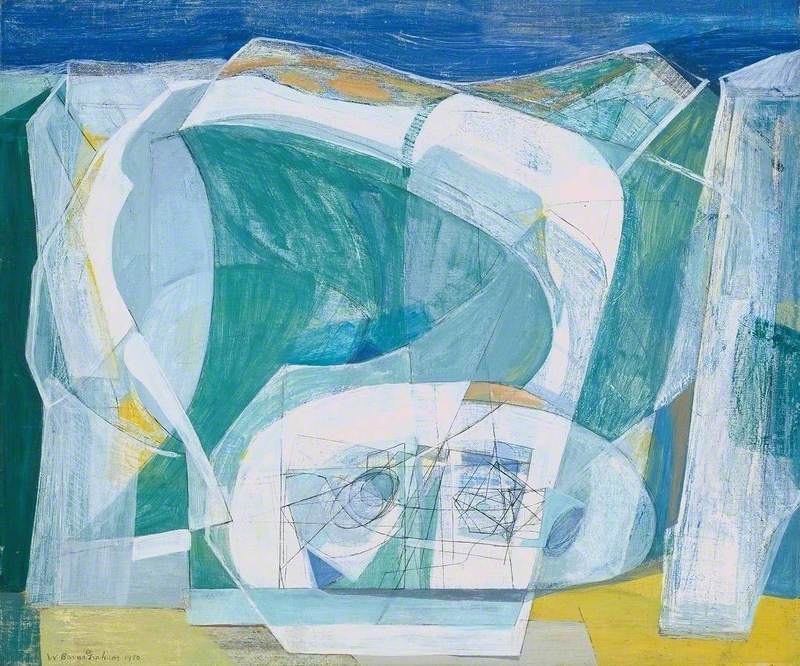

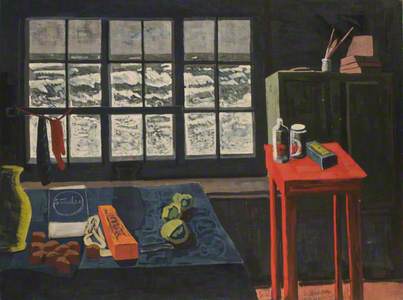

Back in her studio in the Cornish town of St Ives, she produced a series of paintings inspired by what she had seen. These semi-abstract works feature dramatic combinations of sweeping curves and sharp edges: chilly blues, earthy browns, rocky greys, smooth, translucent surfaces and rough-textured ground.

As the artist explained in a letter to the Tate Gallery in 1965, she was attempting 'to combine in a work all angles at once, from above, through, and all around, as a bird flies, a total experience.'

The style of her paintings encompassed the lessons of the St Ives school. But they also set the scene for the rest of her long career: she still had more than half a century of innovation ahead of her.

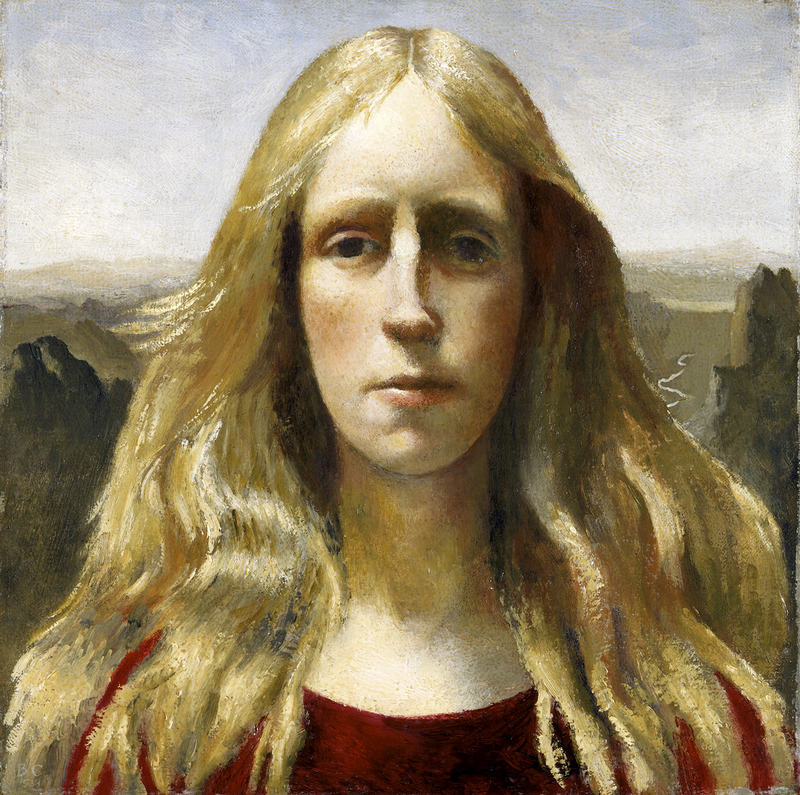

Barns-Graham was born in St Andrews, Scotland, in 1912. Known for having a colourful sense of the world, she (quite literally) had synaesthesia, a condition that caused her to associate colours with everyone she met.

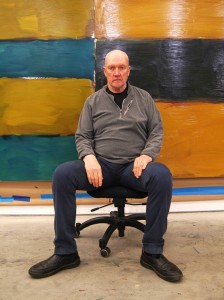

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004) at No. 1 Porthmeor Studio, St Ives

1947, photograph by unknown photographer

Although she wanted to be an artist from an early age, she faced opposition from her father. With the support of her aunt, she enrolled at the Edinburgh College of Art in 1931.

Illness slowed her progress (she suffered from respiratory problems her whole life), but she excelled nonetheless at the College. There, she focused on traditional, tried-and-tested techniques, especially drawing.

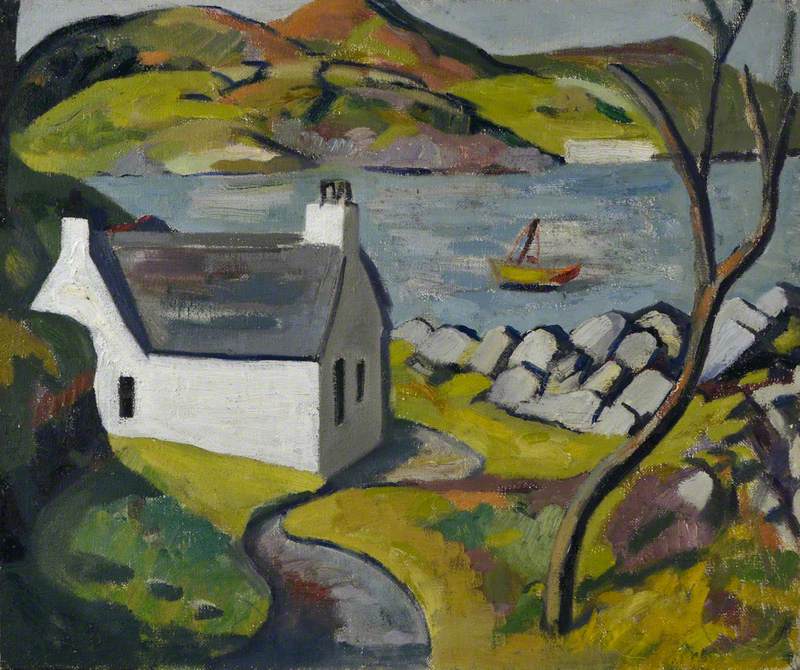

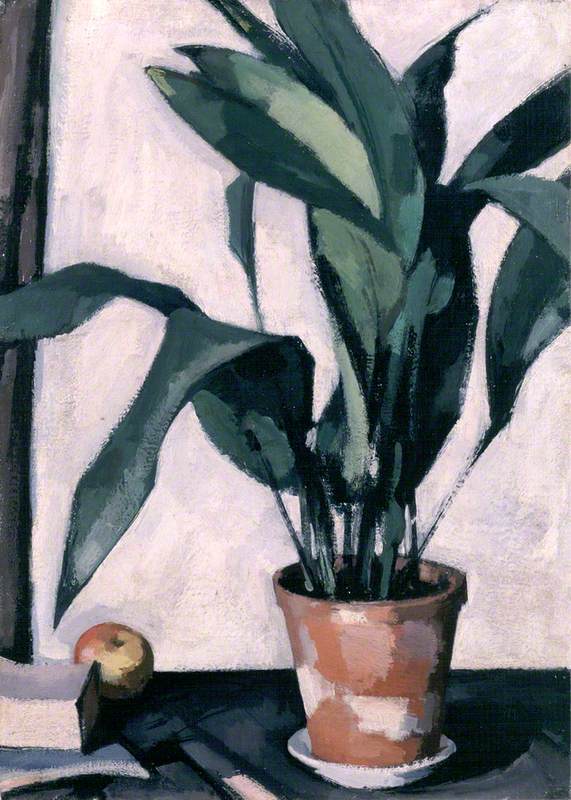

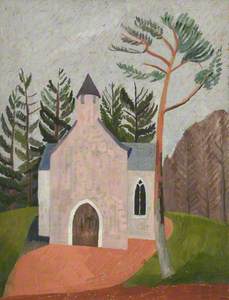

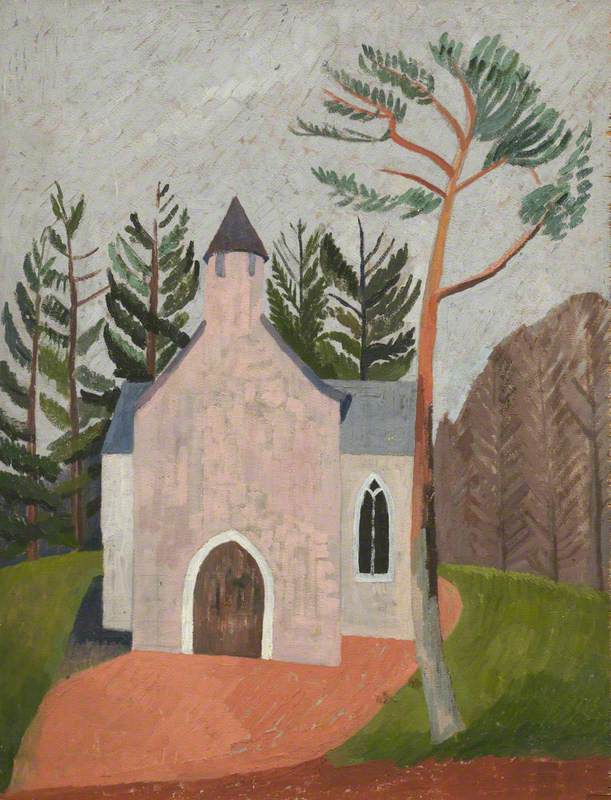

While studying, Barns-Graham discovered a taste for abstraction. The Episcopal Church, Aviemore made in 1938 (a year after she graduated), displays some of the modern traits that she would tease out over time. The details and colours have been simplified and painted in a tightly knit network of brushstrokes to produce a flat, tapestry-like effect.

The Episcopal Church, Aviemore

1938

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004)

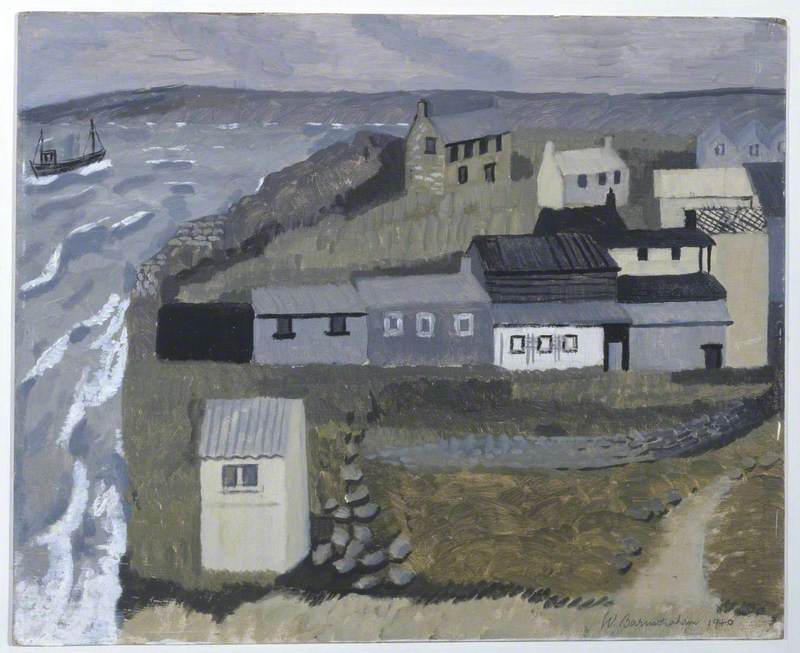

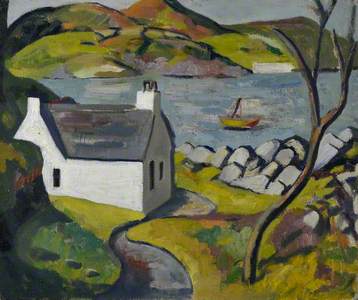

In 1940, Barns-Graham relocated to St Ives, where she would keep a studio for the rest of her life.

By that time, the small fishing village had become an established artistic centre, which welcomed her into a close, albeit quarrelsome, creative community. Other artists residing there included the modernists Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Naum Gabo, as well as several younger artists with avant-garde tastes moving to St Ives after the war.

Like Barns-Graham, many of them were interested in representing the rugged and changeable Cornish landscape using modern techniques.

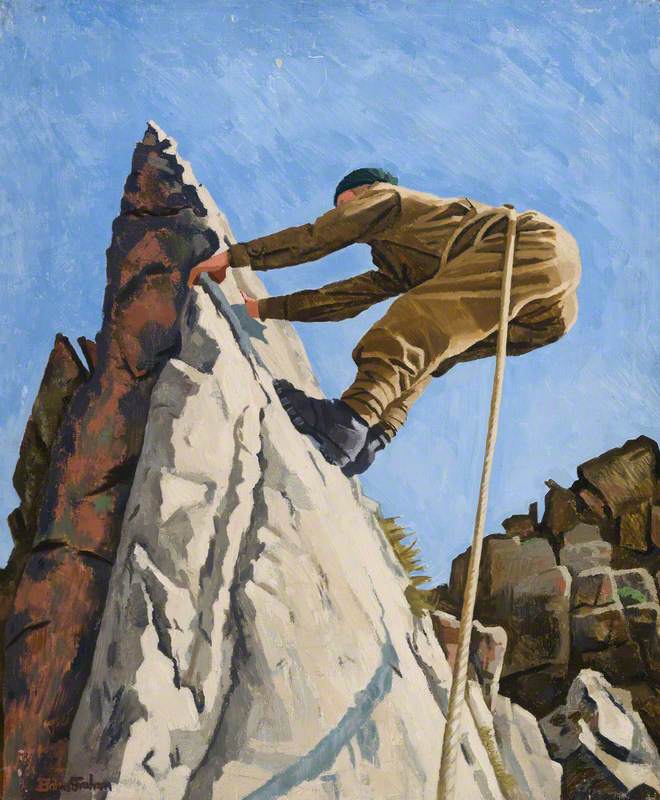

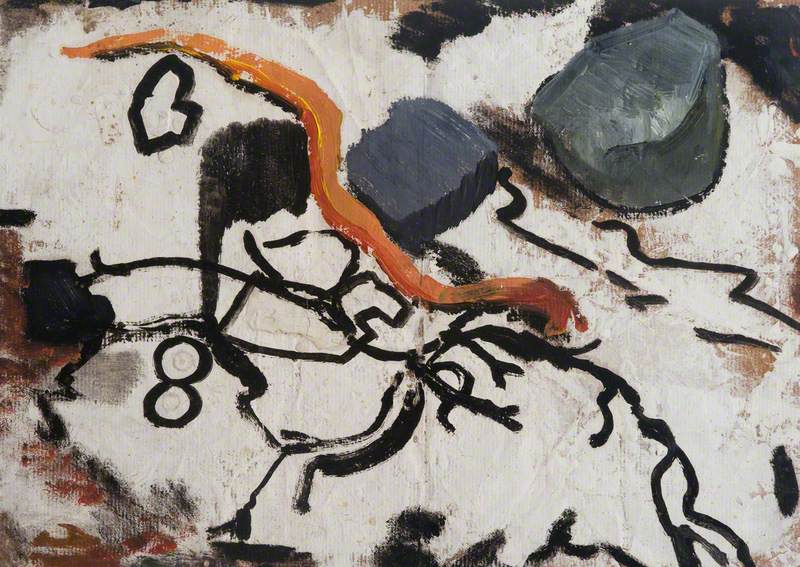

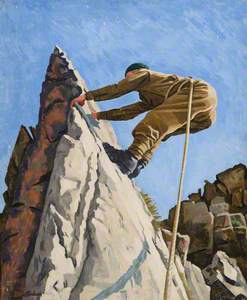

Barns-Graham experimented widely during this period. Her work ranged from straightforward representation, see in the wartime painting Commando on Commando Ridge, 1943, to playful abstraction, as seen in Froth and Seaweed, 1945. In the latter painting, she delights in the accidental patterns formed by washed-up debris.

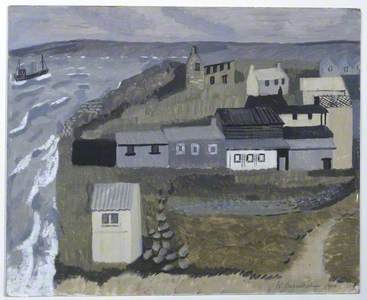

Sleeping Town, 1948, shows how she used modernist methods to convey both the physical structure and emotional tenor of the town she had come to love. There are plenty of identifiable elements, from the boats to the church tower. However, each is distilled to essentials and painted in moody, evocative colours.

The more she painted, the bolder Barns-Graham became in pursuing abstraction. 'It took me some time to have the courage to do the abstract', she reflected later. 'I did do them in 1940, but I hid them.'

By the time she went to Switzerland, she was ready to leap to abstraction. The glacial forms were so unfamiliar, so elemental in their structure and behaviour that they couldn't help but appear somewhat abstract.

From this point onwards, Barns-Graham focused on capturing the general essence of the subject – something she described later as 'nature in motion, working on and changing itself.'

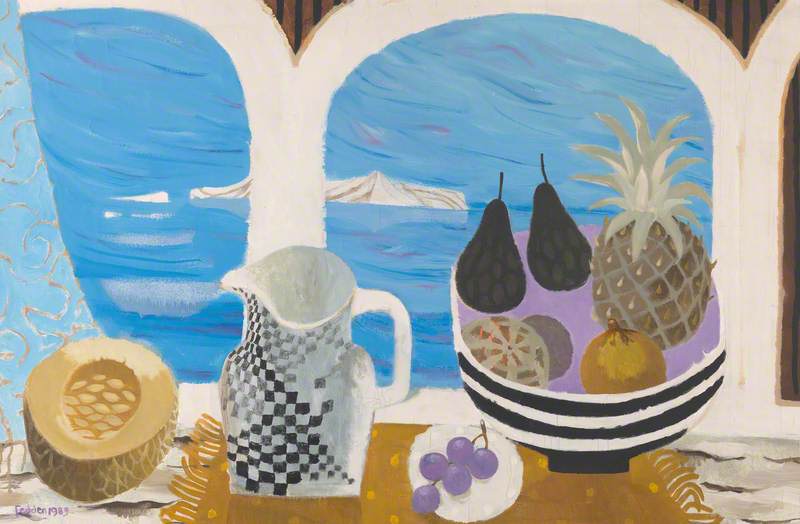

In subsequent decades, Barns-Graham steered her art further away from traditional painting. In the 1950s, she 'loosened up' her style on a trip to the Balearic Islands, translating her experiences of the baking-hot landscape into fiery, freely painted compositions such as Spanish Coast, No. 3 (1958–1959).

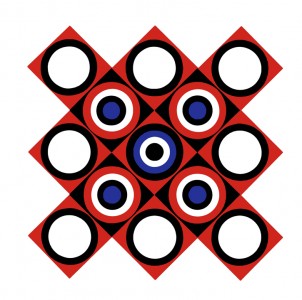

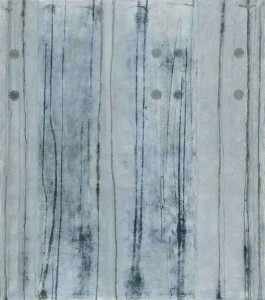

In the 1960s, she shifted her attention again, building composition after composition by spreading cut-out card squares over her studio floor, nudging a few out of order, and painting the results. The simple method had a simple question at its heart: what happens to the order of things when you disrupt a part of the whole? This kind of questioning sustained her work for years. In an interview in 1966, she declared she had been 'painting squares for six years now. I can't stop...They have endless possibilities.'

At first glance, the paintings in this series called 'Things of a Kind in Order and Disorder' have little to do with the natural world. But they represent the elemental forces at the heart of all things. '[T]he square as a form', she once explained, '...typifies the miraculous and seemingly limitless inventiveness of nature, with its underlying structure or order and the fundamental need of any attempted disorder to return ultimately to ordered wholeness.' Barns-Graham had spent decades watching nature 'working on and changing itself,' in different scenarios but always with the same essential rules. Now she was translating that into art. Over time her squares gave way to circles, lines, and other shapes, but the basic idea held.

Of course, Barns-Graham's artistic trajectory was never simple. Her work was as shaped by her emotions, memories, and the joy of painting as by natural laws. In some works, like Pentecost (1971–1976), she channelled religious faith into her meditative artistic process, while her 'Scorpio' paintings from the 1990s are exuberant experiments. Despite her career-long commitment to abstraction, she regularly returned to painting traditional scenes. For example, the gardens in Balmungo – the St Andrews home she inherited from her aunt in 1960.

Barns-Graham repeated the glacier theme at various points in her career, reinvigorating the old palette of blues, greys, and browns in new and inventive ways. She always returned to herself, building on her experiences and observations, while introducing new elements and letting her art evolve accordingly.

When she died in 2004, she left a huge body of work behind and a significant legacy, having helped shape the direction of British modernism in St Ives and beyond.

Her work remains underappreciated. Hopefully, that too will change over time.

Maggie Gray, art historian and writer

Further reading

Lynne Green, W. Barns-Graham: A Studio Life, second edition, Lund Humphries, 2001

Discover a selection of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham prints and gifts on the Art UK Shop