In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

Christine Borland has always been more stimulated by absence than presence. Her work develops from collaborations with scientific, medical and community institutions and individuals, as well as museums – from examining their archives and collections to nurturing relationships with their experts. These journeys lead to intriguing revelations about practices and narratives that aren't always apparent to the casual observer.

Christine Borland spinning as part of her Flax project

Her most recent work, Flax Turns Foundation Cloth, has been a three-year process that involved investigating the heritage of the once thriving, now disappeared, eighteenth-century linen industry in Huntly, Aberdeenshire.

Using original techniques, she has planted, grown and processed flax to spin and weave into fabric, questioning the recovery of these heritage practices for our understanding of sustainable growing and making traditions for the future. The project also included 'In Relation to Linum', an exhibition at Inverleith House, part of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE), in 2021.

Borland, who was nominated for the 1997 Turner Prize, is a part-time Professor of Fine Art at Northumbria University. She was born in Darvel, Ayrshire, and lives and works in Kilcreggan on the west coast of Scotland.

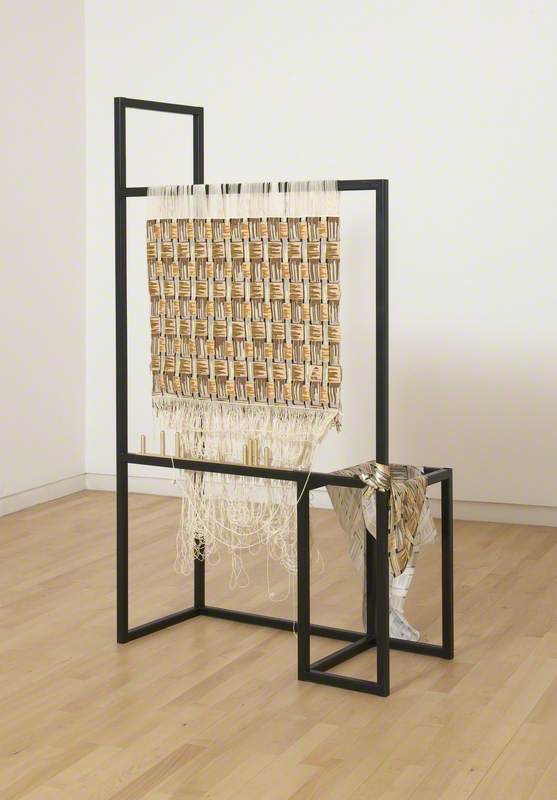

Installation view of 'In Relation to Linum' by Christine Borland at RBGE, 2021

Ashley Davies, Art UK: Can we start with a description of Flax Turns Foundation Cloth, how the idea germinated and your intentions for the whole project?

Christine Borland: Deveron Projects invited me to design a research residency which would lead to a project in the town, so the genesis of the idea was in wanderings around Huntly.

I grew up in a textile town and so much, from the way the River Deveron was dammed to the rows of workers' cottages, felt familiar, yet there was no trace of the skills, workforce and essential role of the linen industry in the town's development.

The project evolved to look at how we retrace lost practices and processes, build relationships around them and project them forward into being meaningful in the future.

Christine Borland sowing for 'In Relation to Linum' at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 2021

I planted flax seeds in my own garden and in Deveron's. The first phase, in 2019, was about the sowing, growing, harvesting and processing of flax. It included the breaking, scutching and heckling, which takes it to the state of pre-spun fibre.

I did all this alongside interested participants in Huntly who were growing with me in their gardens and helping out with the processing. The Highland Folk Museum in Newtonmore kindly lent me some replica equipment for this.

What should have been the next stage – the spinning – changed into something else because a pandemic wasn't the right time for socially engaged practices. During 2020, after a callout on Instagram, it turned instead into an intimate but socially distanced project with participants all over the country growing seed from the previous harvest. In 2021 we restarted the project in Huntly, spinning all of this material.

Christine Borland posting seeds to growers in 2020

Rosie, one of the volunteer growers on the project

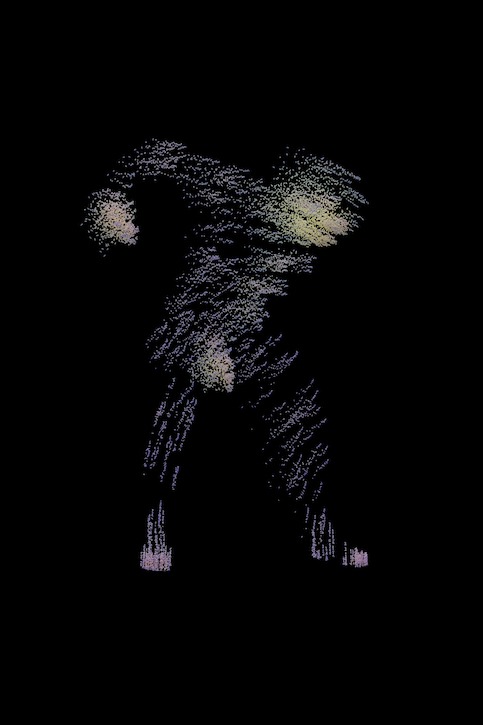

I've focused on looking at the body in relation to all these different processes and practices, questioning how this embodied knowledge is stored, passed on and how it may exist in the future. I worked in a motion-capture studio, wearing a 'mo-cap' suit to record and archive all these movements incorporating the sowing and growing, spinning and weaving stages.

My daughter, Grace Borland Sinclair, who's doing a PhD charting a history of Scottish feminist speculative fiction, has written a response to these practices as if experiencing them from a far future, when we may know nothing about plant husbandry and fibre production.

At home together over the pandemic, we enacted the kind of shared seasonal rituals which would have sustained both society and environment before the modern scientific and industrial era displaced women as growers, healers and makers of cloth.

The Sower's Daughter, Dig

2021, motion-captured 3D visualisation by Christine Borland (b.1965). CGI by John Butler

Ashley: The flax project seems to be a deliberately slow process. Can you tell me about some of your other works that took this long to take root and flower?

Christine: With any project, I could probably take as long as you give me! The research is an iterative, cumulative process and I'm very lucky that experts I met early on in my career continue to be there to ask questions of, alongside new people I meet with every project.

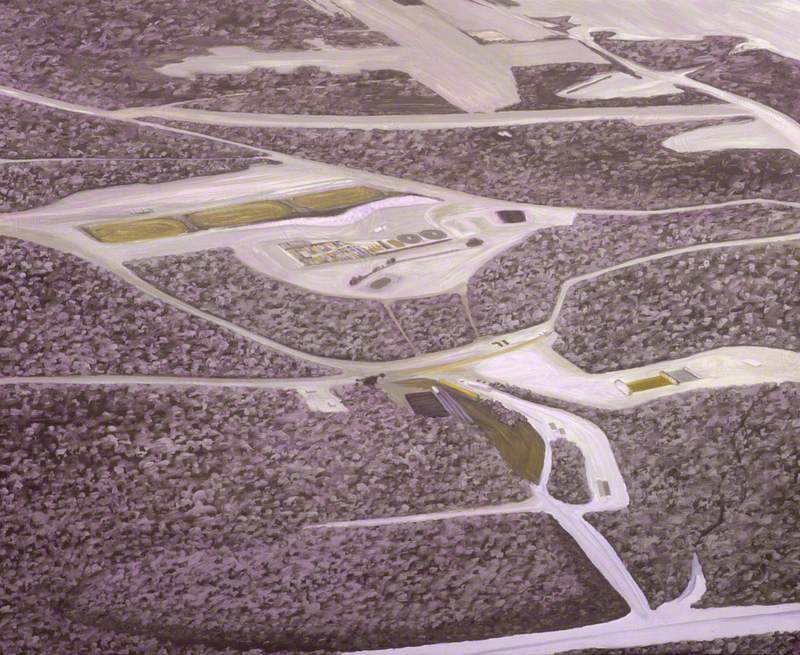

One work with a particularly slow timeframe is To The Power of Twelve at Mount Stuart, 2018. I made a relatively modest scale photographic exhibition there at the beginning of the 2000s, which touched on the incredible history of the house as a Naval hospital in the First World War.

Almost 20 years later, based around the centenary of the First World War, I went back to work in-depth on a major project staged throughout the house. The initial research had really stayed with me and matured in the intervening time, making the works so much richer, I think.

Ashley: Tell me about the impact and influence the Glasgow School of Art's Department of Environmental Art had on your early practice.

Christine: It really taught me the value of building communities of practice, valuing the support of peers and the interconnectedness of art and life. A lot of it was learning how to develop lasting relationships based on fun: through eating, talking, playing, dancing together, all of which I still regularly employ!

The department's mantra, borrowed from the Artist Placement Group, was 'context is half the work'; we were always thinking about where the work would be developed and sited, who would experience it and how. Even with work in a white cube gallery, space is only activated when filled with people, their ideas and experiences.

Ashley: Your practice involves painstaking research and collaboration with experts and academics across a number of disciplines. Given that so many areas are connected, how easy is it to remain focused on the work in hand, or do you allow yourself to be absorbed by related strands of information that could take you down other fertile avenues?

Christine: Whether it's formalised or informal, I always incorporate a period of research that's about asking open-ended questions, building relationships with people, following wrong turns and making U-turns. It's an exciting time of ranging around that I absolutely love in new projects.

Equally, I enjoy coming back to deep veins of thinking when I need more quiet reflective time to play with materials in a studio-type environment (which could be a lab, museum archive or my garden) to connect intuitively with the new research and ideas.

Ashley: Where did your interest in medical subjects come from, and can you talk us through some of your works that were stimulated by this area?

Christine: I was brought up in the countryside. My parents, who both worked in lace factories, had a deep knowledge of nature which they passed on just through caring for me – going walking, fishing, swimming and teaching me the names of plants and creatures. I was always getting plastered with different types of leaves for sores or stings and making collections of pressed flowers and dead insects.

I trace my interest in the medical side of things back to the early GSA days. I was terrible at compulsory life drawing but very interested in how the body is represented and preserved.

We were taken to Glasgow University's Hunterian anatomy collection and I immediately knew that I wanted to engage more sculpturally with the body in all its complexities and ethical questions in that kind of context.

I spent a formative period doing my MFA in Belfast in the late 1980s, experiencing life among traces of violence. When I came back to Scotland, I processed all that by talking to and working with ballistics experts on shooting ranges, and looking at forensics practices that reconstruct from small fragments.

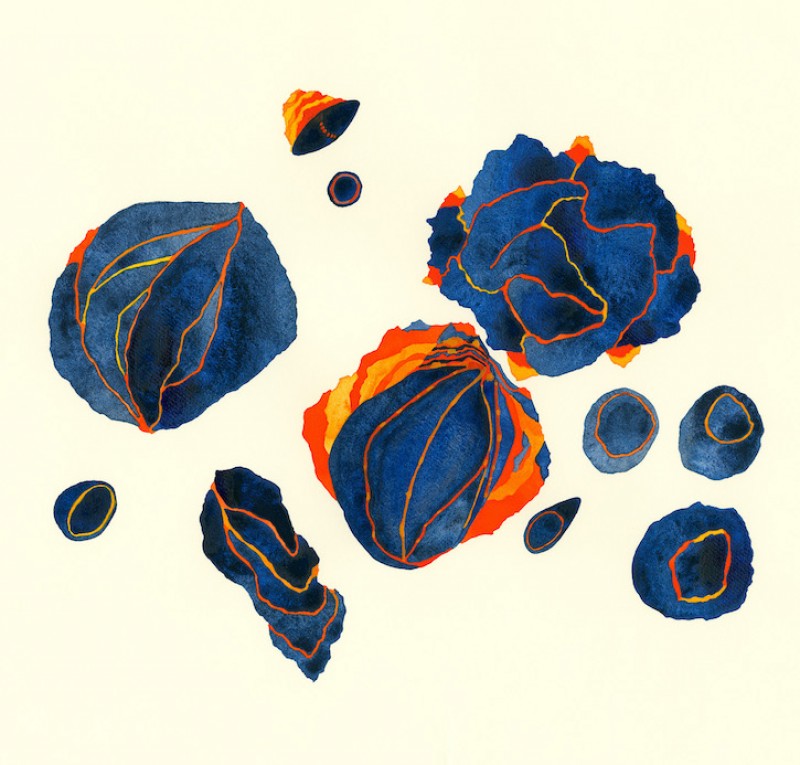

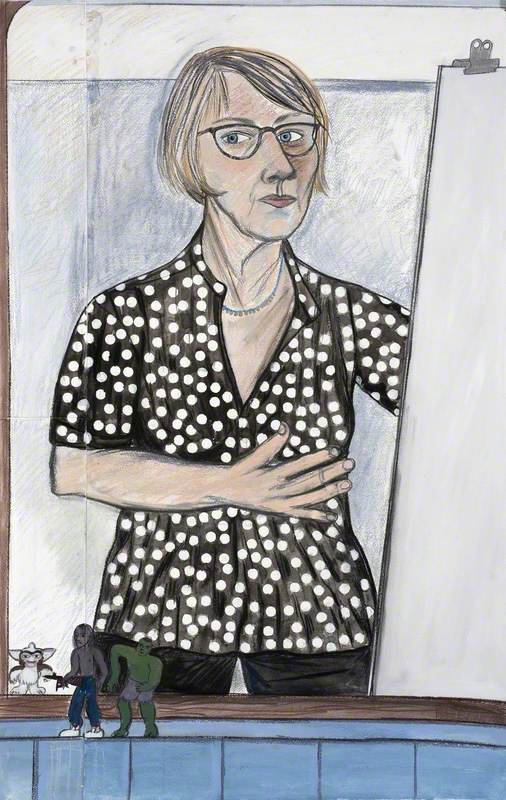

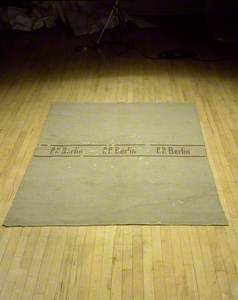

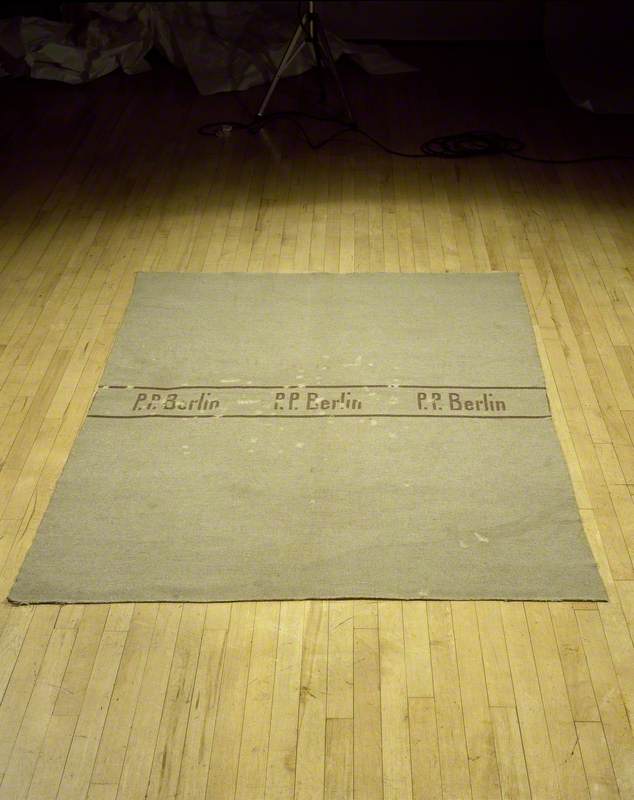

Some of my early works incorporated both shooting as a medium and attempts at repair, like Blanket Used on Police Firing Range, Berlin: Repaired, 1993, and another early work, The Velocity of Drops (my first exhibition at Mount Stuart), was drawn from forensic processes examining blood splatters and droplets left at scenes of crimes, replicated in dropped melons; The Velocity of Drops series, 1993 to the present.

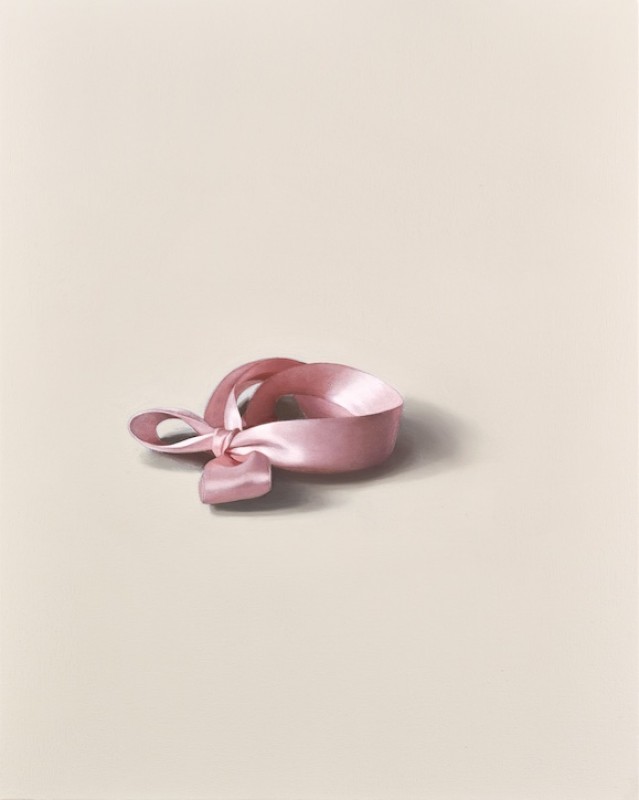

Blanket Used on Police Firing Range, Berlin: Repaired

1993

Christine Borland (b.1965)

Ashley: Have your intentions ever been misinterpreted or misunderstood?

Christine: Miscommunication is par for the course when you do research that involves negotiating and asking difficult questions of people you may have just met. I try to build in as much time as I can for that because it's fundamental to making the work, I'm often beholden to people in their workplaces being willing to share their precious time and expertise.

Sometimes misunderstandings lead to something really interesting and exciting developments I can't have anticipated. Miscommunications are part of the process.

Ashley: Can you tell us about what you're planning to do next?

Christine: There are stories and practices that have been lost all over the world relating to plant-based materials and the associated passing on of traditional knowledge. These, often matrilineal, chains of knowledge have usually been broken through extractive practices related to colonialism. I would love to learn more about these histories, how they are being recovered and how they relate to what I've learned through Flax Turns Foundation Cloth.

I've also been thinking about some of the burial traditions and forensics practices that I've looked at through my career and their relationship to the intimacies of linen and other kinds of burial cloths in relation to the body.

Ashley Davies, freelance journalist