In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

For the past two decades, Carolina Caycedo has investigated the environment as a human right. The Colombian artist, who was born in the UK but now lives and works in Los Angeles, has developed publicly engaged projects with local communities and environmental activists across the globe, in Bogotá, Quezon City, Toronto, Madrid, São Paulo, Lisbon, New York, Paris and London among many others.

Performance view, Carolina Caycedo in 'Atarraya', Phoenix, 2018

Her latest solo show, 'Carolina Caycedo: Land of Friends' at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead (until 29th January 2023) features seminal works from the artist's oeuvre, highlighting her varied practice and video installation pieces such as Spaniards Named Her Magdalena, But Natives Call Her Yuma (2013). Weaving together research from her visits to international dam sites – from Germany's Black Forest to the Rio Magdalena region in Colombia – such works conflate scientific research, human stories and the artist's personal reflections.

Her spiritual approach to creating environmentally engaged art illuminates the social power structures and mechanisms of control exerted by multinational corporations, which threaten precious water reserves, ecosystems and human communities. To coincide with her show at BALTIC and her participation in the Serpentine group show 'Back to Earth', Art UK speaks to the artist about her broader practice, the problematics of greenwashing in contemporary art, and her relationship with the UK.

Patron Mono

2022, installation by Carolina Caycedo (b.1978)

Lydia Figes, Art UK: In your video Spaniards Named Her Magdalena, but Natives Call Her Yuma you reflect on your early experiences with water, including one from childhood. Could you take us back to that moment and how it formed your interest in water as an artist?

Carolina Caycedo: 'I've always been close to water. I used to swim and I did this competitively until I was 14. As a family, we would spend our weekends doing trips to rivers. We'd cook soup by the river, swim and fish there. The experience of swimming in a river is very different to swimming in a pool.

As a child, I would struggle to cross the river when the current was strong. There was a particular incident when I was about eight or nine, and my grandfather could see that I was struggling. He jumped into the river to show me how to swim with the current. He let it drag him a little bit, swimming with the current rather than against it. This metaphor is an important one in life generally. It applies to our relationship with natural entities – water, wind, the forests. We need to go swim and grow along them – not against them. The latter is a colonial and extractivist way of relating to natural entities.

Spaniards Named Her Magdalena, But Natives Call Her Yuma

2022, installation by Carolina Caycedo (b.1978)

Lydia: YUMA, or the Land of Friends (2014) developed out of interest in the damaging impact of dams, especially on indigenous communities. Can you explain the formation of this work and the evolution of the Be Damned project more largely?

Carolina: Be Damned is a constellation of works, it's a big web of concepts and forms that has developed over time. It started in 2012, with a case study of the Magdalena river in western Colombia.

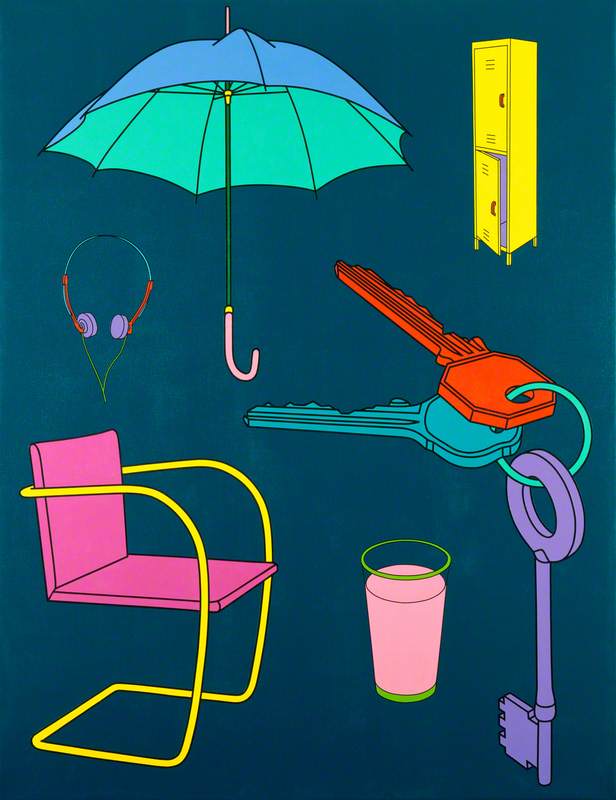

YUMA, or the Land of Friends uses satellite imagery and aerial photography to subvert the colonial gaze over land or water – territories that have been extracted by humans. It offers a multilayered view of a territory to complicate the colonial gaze. It subverts that view of power – the satellite view used by extractivist companies to gaze over the advancement of their construction projects.

YUMA, or the Land of Friends

2022, installation by Carolina Caycedo (b.1978)

The work is a photo collage subverting the militaristic view of the satellite. It aims to suggest that even if these satellite images are high resolution, they remove particularities about the cultural diversity that exists in that territory – you can't see the species of trees in the forest, or types of fish in the river.

Lydia: You have described your process as 'spiritual fieldwork'. Could you describe how this approach manifests in your work?

Carolina: 'Spiritual fieldwork' is basically about commitment. It's a commitment to the rigour and methodologies of doing fieldwork, collecting information, data, objects, images. Listening to testimonies, going through archives. There's a rigour in the methodology. It requires being in the field to understand, to feel. When you start thinking and feeling at the same time that activates a spiritual dimension. It allows me to offer a commitment to those communities.

The patriarchal fieldwork speaks about an objective perspective over the object of study. For me, it is the contrary. My intention is to get closer in all senses to the land, water, the communities of that territory.

Lydia: Your installations feel like immersive worlds or alternative habitats, and you have described art as like 'casting a spell'. Is the aim to provide the viewer with a transformative experience that will change their human-centric perspective on nature?

Carolina: Casting a spell has to do with tapping into as many senses as I can. Art has a lot of power to do this and to stir empathy. The idea is to tap into senses to generate empathy, and ultimately provide statistics and data in a way that is not cold, empirical and boring. It should spark an interest and challenge the way we relate to nature, which is currently permeated through a colonial perspective.

Spaniards Named Her Magdalena, But Natives Call Her Yuma

2022, installation by Carolina Caycedo (b.1978)

Lydia: Your practice resonates with the legacies of eco-feminism, in the sense that your work draws connections between caregiving and empathy with environmental and feminist activism. Would you define yourself under the term eco-feminism?

Carolina: I definitely draw from feminist practices and am inspired by them, especially the 'politics of care.' This idea of transformation and transition is an integral part of the processes we see in the natural world, in that sense, women and woman-identifying people have been my mentors and teachers. I see these people on the frontlines of indigenous and environmental struggles all the time. I consider myself an eco-feminist, yes. But I tend to move away from using categories because they can take away agency from us, I use categories such as 'activist' with care. I like to insist on my identity as an artist, with the skills of creating, constructing and deconstructing images and concepts. That's the field from which I operate and struggle.

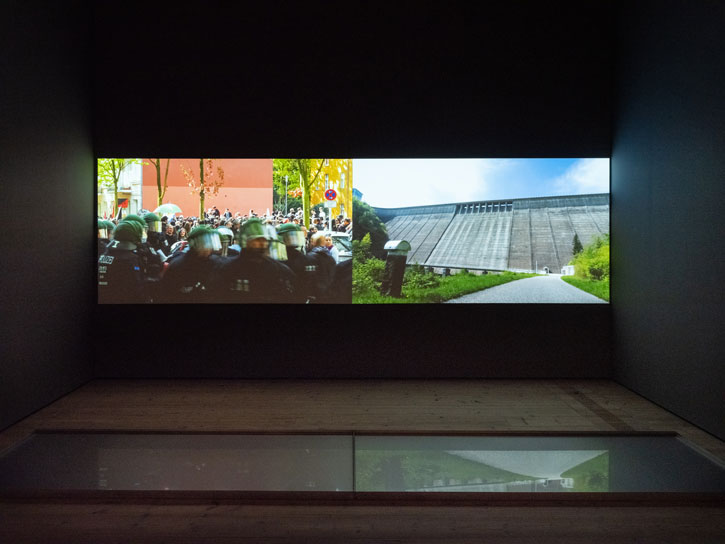

Installation view of 'Carolina Caycedo: Land of Friends'

Lydia: In past interviews you have expressed scepticism with terms such as 'sustainability', preferring words such as 'sustenance'. Do you feel that the art world co-opts environmental buzzwords and thus green washes content?

Carolina: This idea of co-optation is something I'm discussing a lot at the moment, especially with local communities and in Colombia. 'Transition' has become a bit of a buzzword in the art world. You often hear things like 'transition into sustainability', or 'transitions to green energy'. It has become a fashionable subject matter and there is a lot of funding for environmental-themed exhibitions right now.

Installation view of 'Carolina Caycedo: Land of Friends' at BALTIC

But beyond that, the truth is that environmental collapse is a real concern across disciplines. There are a number of cultural practitioners who are working deeply with these subjects matters, who are thinking about how art can support the agendas of people on the frontlines of these environmental movements. I trust creative initiatives that work closely with real communities and organisations that are advancing the movement.

Something I am questioning more in my practice, is the question of how are we going to compensate for all of the carbon footprints that the production of art leaves? Behind exhibition making, there are emissions directly created from transportation, production of works, the sourcing of materials. How can we start to think about cutting those emissions or think about compensating for the damage we leave in an ethical way?

Carolina Caycedo, How to Obtain a British Passport, 2003 on Vimeo.

Lydia: As an artist who was born in the UK to Colombian parents, what would you say your relationship is like now with the UK? Could you explain the idea behind your 2003 video work How to Obtain a British Passport?

Carolina: The UK is part of my personal history. I was born there and lived there until I was six before returning as an adult to go to art school. I made strong relationships with other cultural practitioners in London, relationships that continue to enrich my practice today. It's a very important part of who I am as a person and artist. It gives me a lot of pride and joy to have a solo presentation at BALTIC, and to represent this transnational identity, which is how I perceive the UK today. Politically speaking, Britain seems to be closing in on itself, though it wouldn't be the same without the history of migration. But culturally, the scene in the UK feels very open and vibrant.

My piece How to Obtain a British Passport (2003) was a commentary on that – it was questioning who deserves citizenship or not. It's also a comment on the absurdity of certain laws that prevent basic rights for migrants. This work treats the subject with humour and irony, but is highlighting the plight and difficulty of migrants today. It's an old work, and I see it now as a naïve work, but looking back at it 20 years later it feels more relevant today.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

'Carolina Caycedo: Land of Friends' is on at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead until 29th January 2023