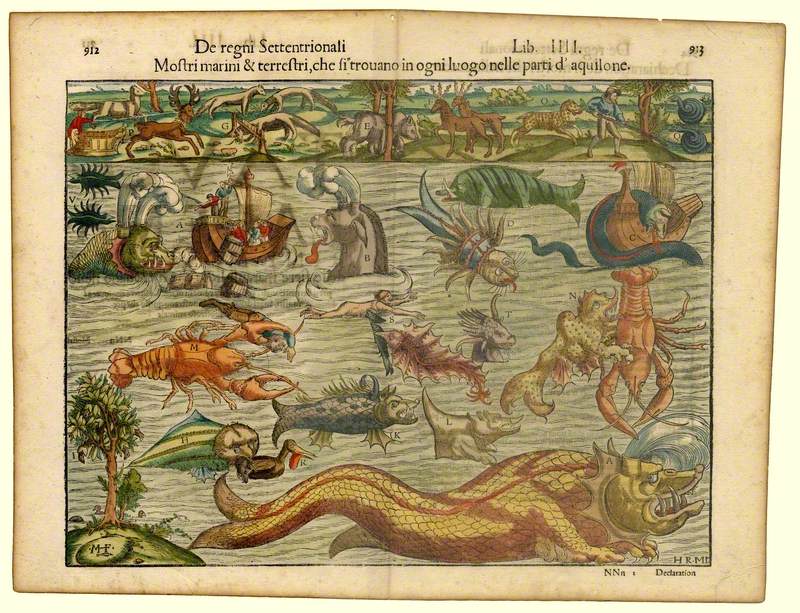

'I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas'

– T. S. Eliot in 'The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock'

'These new images belong to the iconography of despair or of defiance; and the more innocent the artist, the more effectively he transmits the collective guilt. Here are images of flight, of ragged claws "scuttling across the floors of silent seas", of excoriated flesh, frustrated sex, the geometry of fear.'

– Herbert Read

In 1952 the careers of Lynn Chadwick, Reg Butler, Kenneth Armitage and Bernard Meadows were launched on the world stage at the 26th Venice Biennale. 'New Aspects of British Sculpture' in the British pavilion was an international sensation. With Elisabeth Frink, the work of these artists forms the core of the 'Being Human' exhibition at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery (until spring 2021).

The art historian and critic Herbert Read's phrase 'the geometry of fear' resonated with the sense of pain, guilt, aggression and helplessness in their work. The sculptures of this generation of survivors from the Second World War were a departure from the smooth monumental masses of Moore and Hepworth. They were cut, assembled, welded in metal. They were rough, sharp, spiky and twisted. Everything about their design was the opposite of tactile: they were on the defensive.

Today art historians argue that Read overemphasised his point. Some artists disliked how the phrase attached to their work. The imagery was criticised by younger sculptors such as Philip King, who said, 'It was somehow terribly like scratching your own wounds, an international style with everyone showing the same neurosis.'

But the pavilion put British sculpture on the map. Alfred Barr, the director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, purchased several pieces for the museum, proclaiming, 'It seemed to many foreigners the most distinguished showing of the Biennale.' And he wasn't the only one – Peggy Guggenheim and Elsa Schiaparelli were also buying.

The Second World War stole five or six years from the lives of the Geometry of Fear artists and their generation. Several began the war as pacifists, joining up later. The discovery of the death camps was shattering and while optimism manifested in the post-war settlement of government support for welfare and culture, it was partially shadowed by the threat of nuclear war.

Lynn Chadwick resisted over-interpretation: he wasn't keen on Read's term. But he agreed that his work was inherently psychological. He said, 'it seems to me that art must be the manifestation of some vital force coming from the dark, caught by the imagination and translated by the artist's skill... when we philosophise upon this force we lose sight of it. The intellect alone is too clumsy to grasp it.'

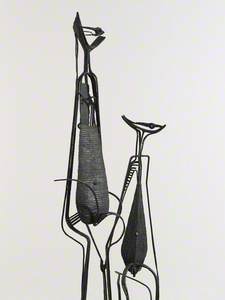

Idiomorphic Beast won him the sculpture prize at Venice in 1956, four years after 'New Aspects of British Sculpture'. This unique fusion of welded iron rods is an alien form. Chadwick didn't attend art school and worked intuitively, taking his motifs from nature. The tented webs of breast-like forms of the Beast indicate the sexual awkwardness or abjection that Read hinted at. Chadwick shared this with Reg Butler, calling his figures, 'sculptural metaphors for the essence of animality.'

There was controversy about the younger Chadwick beating the renowned Giacometti, but Alan Bowness described him as a revelation: 'The Biennale award marks the emergence of Lynn Chadwick as a figure of international artistic importance.'

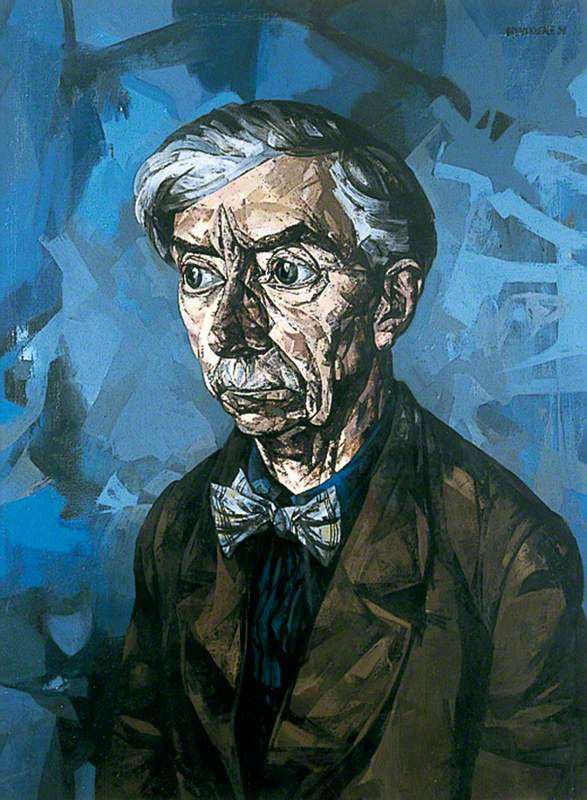

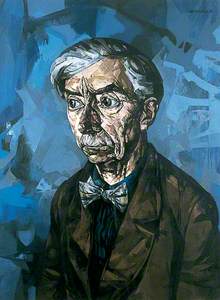

Reg Butler grew up in the workhouse his parents managed. Close to a maternity ward, an asylum and old people's home, he encountered 'birth, life, difficulties and death' from childhood. This Victorian setting inspired narratives in his art, which he interpreted through a Freudian framework. The human body was his most enduring subject.

But there is a manifest ambivalence in his treatment. Girl balances barefoot on a rung, clearly a posture of discomfort.

The art critic John Berger described Girl as a sculpture of two halves – 'tender and sensuous almost to the point of sentimentality' (the flower-like face, looking up and away) and below (the naked pudendum) 'brutal to the point of disgust'.

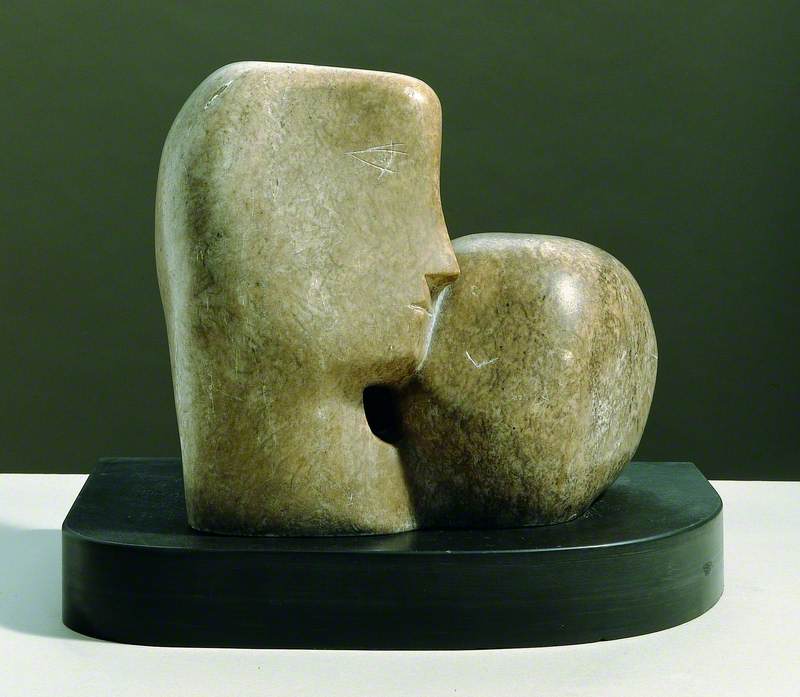

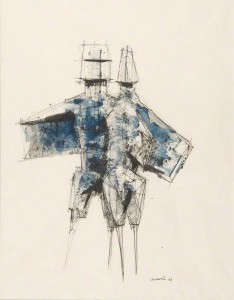

In comparison, Kenneth Armitage's sculptures express human vulnerability. Moon Figure is unique and predates the Biennale. It offers a key to the visual language Armitage was developing. It was originally carved in wood, and then in Portland stone.

As he said, 'I was interested in the simple inverted big shapes and the rest for arms; and the flatness which has continued in my work indefinitely.'

All of the Geometry of Fear artists shared the Modernist admiration for world and ancient cultures. With its wide shield-shaped face and folded arms Moon Figure borrows from the Cycladic figures Armitage studied at the British Museum. The open face contrasts with Butler's 'iron waifs' and Chadwick's 'vicious teeth and claws'.

Bernard Meadows created sets for Sartre's play The Flies.

His early crab and bird works are aggressive, as if to repel or repulse the viewer.

As Penelope Curtis described it, 'our situation in the world is between threat and defence', and Meadows's sculptures veer between the 'physical manifestations of the predator, the vulnerable, the protective.'

Help (Opus 81) is an abstract meditation on alienation and despair. The brutality of the spherical form being crushed between two hard blocks comprises vulnerability and aggression. There is an existential numbness in this detached depiction of violence.

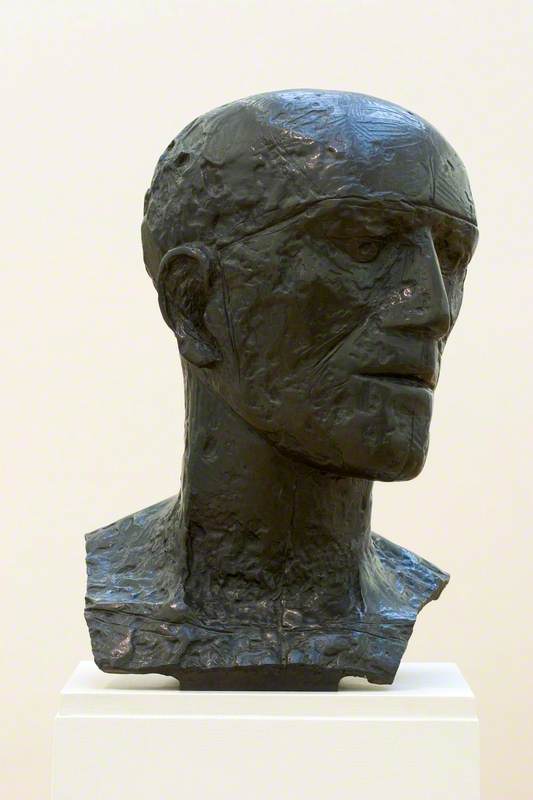

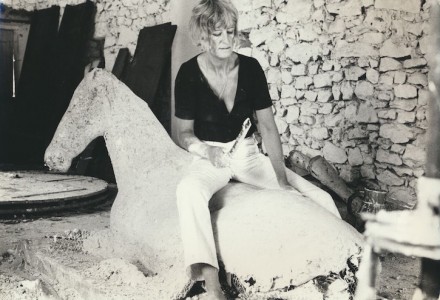

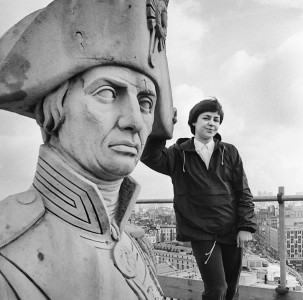

Elisabeth Frink was a student when the term Geometry of Fear was coined. She had had a solo show, exhibited with the London Group and at the ICA and internationally, and Tate had acquired her work. She was just 22.

In the 1960s she created her famous 'Goggle Heads', loosely based on General Oufkir, of French colonial Morocco, who was rumoured to have 'disappeared' his political enemy Mehdi Ben Barka. Oufkir's sunglasses became the motif for Frink's fascistic figures. The predators seem to be the logical end to Frink's portrayals of vigorously masculine men. The opposite of these portraits of masculine violence were the 'Tribute Heads', such as Prisoner.

Since the war, Frink had been interested in the plight of the victims of regimes, 'who are not allowed freedom of thought, who are being persecuted for their politics or their religion, or being deprived of the dignity of daily living and working.'

These are the victims of the 'Goggle Heads'. Prisoner was a gift to Bristol Museum from someone who had been a prisoner of war and knew exactly what Frink was describing.

Frink's career exemplifies what happened to the Geometry of Fear artists: they experienced fantastic success in a very short space of time. Then they were eclipsed by the so-called New Generation sculptors led by Anthony Caro. Or perhaps by the more optimistic mood of the 1960s?

Nevertheless, they remained successful – Frink was the first woman invited to be president of the RA (she turned it down). All had commissions for public sculpture around the country. So to some extent, they became the establishment.

Today we can reappraise their achievements. The unflinching gaze levelled at the darker interiority of humanity created a visual language for their time.

Artists have returned to the mood of the Geometry of Fear in mediums from installation to video, and back to figurative sculpture, whether it's the so-called Morbid Manner of the Young British Artists (Tracey Emin, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Marcus Harvey), or the human everyman (Antony Gormley).

But in the end, the Geometry of Fear artists created a very specific vision of the post-war mood in Britain.

Julia Carver, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery

Further reading

Alan Bowness, Lynn Chadwick, Methuen, 1962

Alan Bowness and Penelope Curtis, Bernard Meadows, Sculpture and Drawings, Henry Moore Foundation, Lund Humphreys, 1995

Kenneth Armitage interview National Sound Archive Artists' Lives, John McEwan and Tamsyn Woollcombe

Richard Calvocoressi, et al., Reg Butler, Tate, 1983

Andrew Causey, Sculpture since 1945, Oxford History of Art, 1998

Penelope Curtis, Sculpture 1900–1945, Oxford History of Art, 1999

Ann Elliott, ed., Kenneth Armitage, Sculptor: A Centenary Celebration, Sanson & Company, 2016

Albert E. Elsen, Pioneers of Modern Sculpture, Hayward Gallery, Arts Council, 1973

Dennis Farr, Lynn Chadwick, Tate, 2004

Sandy Nairne and Nicholas Serota, eds., British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1981

Herbert Read, Modern Sculpture: A Concise History, Thames and Hudson, 1964, reprinted 2001

Calvin Winner, ed., Elisabeth Frink: Humans and Other Animals, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, 2018