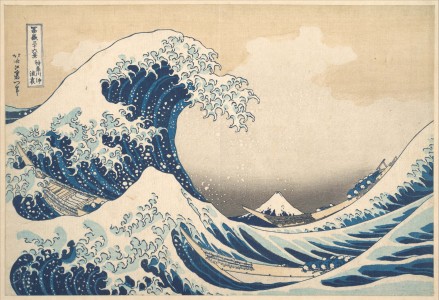

In 1919, Katharine Cameron (1874–1965) held an exhibition of her etchings at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC where she was praised by The American Magazine of Art for being among those rare printmakers who were able to render both the form and the spirit of Japanese art. This comparison illustrates the continuing impact that ukiyo-e prints (a particular genre of Japanese printmaking that flourished from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries) had on Scottish printmakers well into the twentieth century.

It also implies an influence that went well beyond the formal properties of printmaking to one which conveyed the essence of Japanese art. Embracing both the techniques and subject matter of ukiyo-e prints appears to be specific to women artists of the early twentieth century in Scotland. In contrast, male artists of the period adopted the technique and compositional devices of these prints while taking little notice of the content.

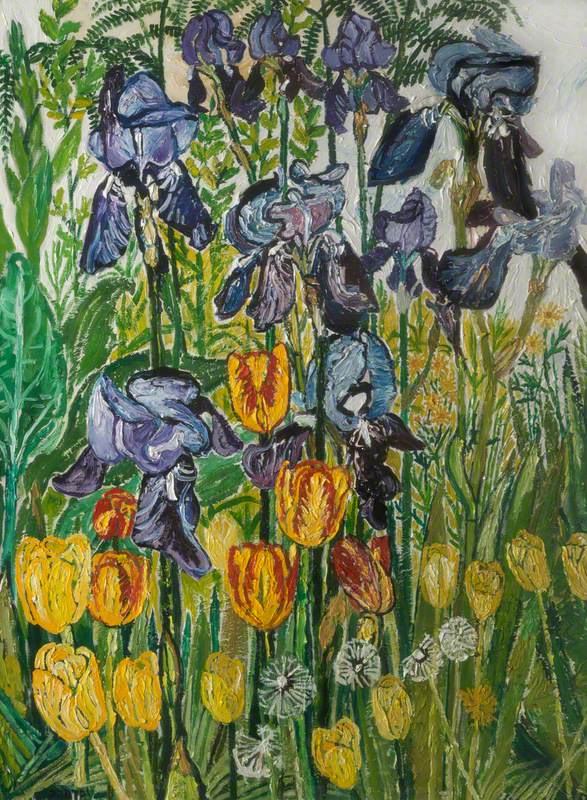

Peonies and Butterfly

c.1827–1839, woodblock print by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Japanese prints began circulating in avant-garde art circles in Paris in 1856 when the printer Auguste Delâtre shared 15 volumes of Random Sketches by Hokusai with Felix Braquemond who, in turn, showed them to James McNeil Whistler. Whistler moved from Paris to London in 1859, bringing with him a growing collection of Japanese art. Three years later, the London International Exhibition featured the Japanese art collection of Sir Rutherford Alcock, the first consul general to Japan from Britain. By the 1860s, Japanese prints and art were well known in Britain and quickly became influential in defining the modernist aesthetic.

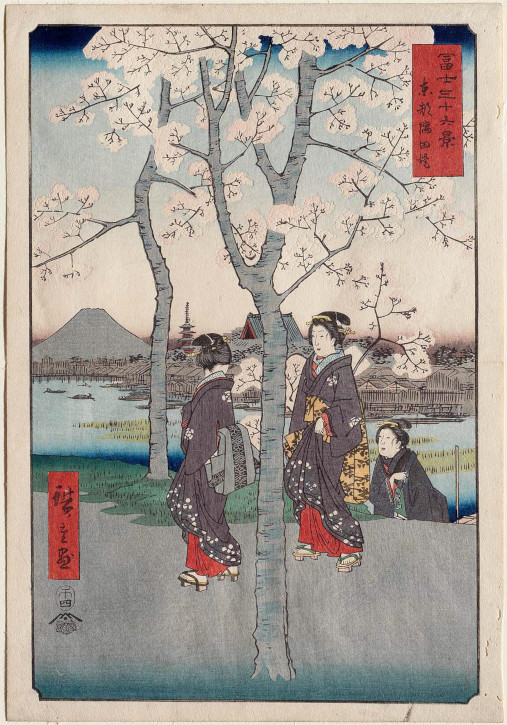

The Sumida River Embankment in Edo (Tôto Sumida-zutsumi)

1858, woodblock print by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858)

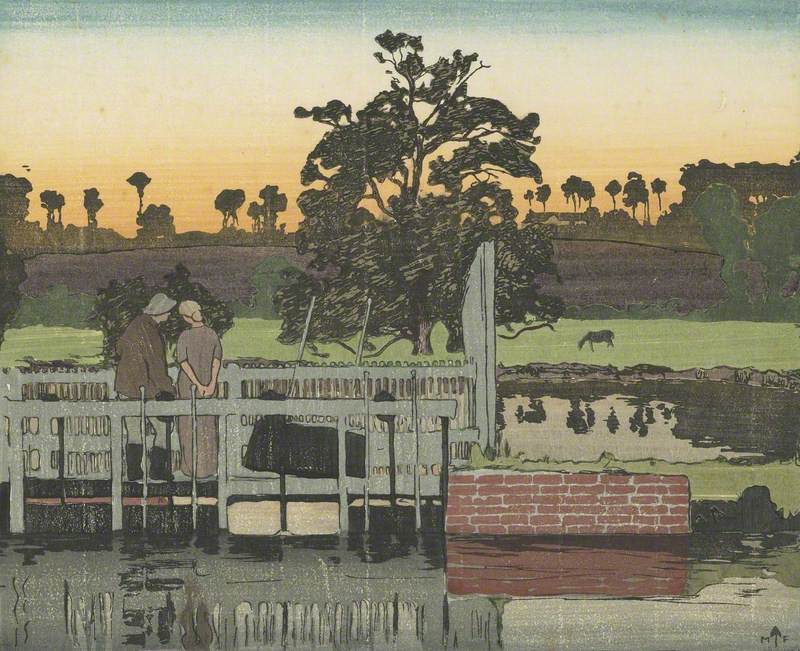

Frank Morley Fletcher (1866–1949), the director of the Edinburgh College of Art from 1907 to 1923, first discovered Japanese prints as a student in Paris in the 1880s. He became intrigued by the process of creating woodblocks in the traditional manner and studied a pamphlet printed by the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC entitled Japanese Wood-cutting and Wood-cut Printing.

Morley Fletcher not only perfected the technique of woodblock printing, but he also incorporated printmaking into the curriculum of the Edinburgh College of Art, influencing a generation of artists including his fellow instructor, Mabel Royds (1874–1941). In 1916, he published Wood-block Printing: A Description of the Craft of Woodcutting and Colour Printing, which just three years later was declared the authoritative textbook on the subject by Malcolm Salaman in London magazine The Studio. Morley Fletcher was credited with laying the groundwork for the success of woodblock printing in Britain.

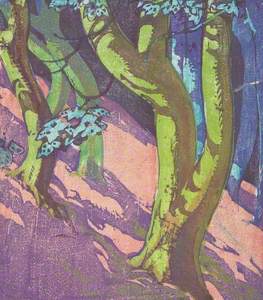

Morley Fletcher adopted the multi-block printing technique and format of ukiyo-e prints in his colour woodcuts. He also took on numerous compositional devices from them, including flattening the picture space by creating a sharp juxtaposition between foreground and background elements, accentuating pattern through repetition, using large areas of flat graduated colour and cropping landscape elements. Morley Fletcher perfected the technique of ukiyo-e printmaking, yet according to his friend and fellow artist, Joseph Pennell, 'he had not in any way tried to imitate the Japanese subjects or made copies of them, but he has carried out the feeling of the English – country... in his color prints.' For Morley Fletcher, then, Japanese prints were more about the technique and formal elements, less the content and the subject matter.

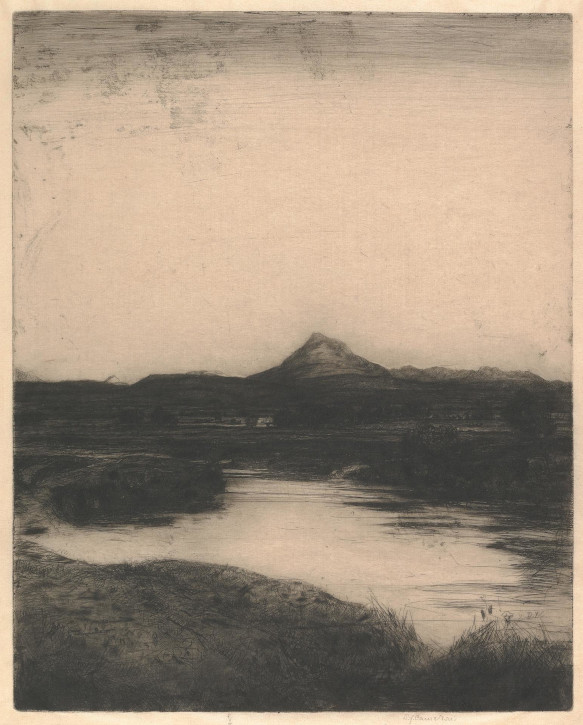

Ben Ledi

1911, etching & drypoint by David Young Cameron (1865–1945)

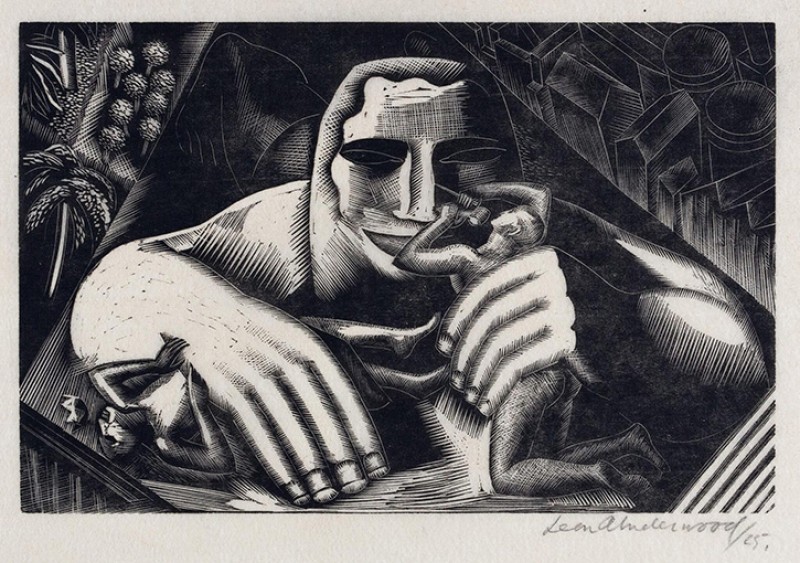

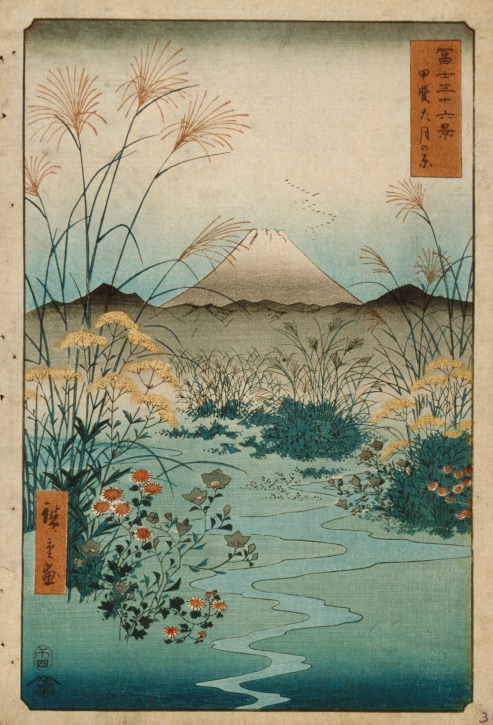

The same appears to be true with etching revival artists of the period, including the most renowned of the group, David Young Cameron (1865–1945). In Ben Ledi, the composition draws much from Japanese compositional devices including the high horizon line, the sparsely engraved and flattened foreground space, and the sharp juxtaposition between the floral element in the foreground and the abstracted trees in the background. Cameron, like Morley Fletcher, was a collector of Japanese prints; included in the donation of his collection to the Perth Museum and Art Gallery at the time of his death was a print by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) from his series of views of Mount Fuji. It is worth noting that Cameron made multiple views of sights near his home in Kippen, Stirlingshire (including Ben Ledi), something that Hokusai had also done in Japan.

The Ōtsuki Plain in Kai Province (Kai Ōtsuki no kei)

1858, woodblock print by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858)

Given the direct influence Japanese prints had on Cameron's work, it is interesting to note that in his own writings and in reviews of his prolific printmaking career this influence was not mentioned. Cameron wrote essays on the old masters – including Rembrandt and Michelangelo – and critics often cited the influence of Rembrandt and Charles Méryon on his prints. Frank Rinder, in his 1908 catalogue on Cameron's etchings, summed up the consensus among critics when writing that Cameron 'would not, indeed, be the artist he is unless Rembrandt had, so to say, become native in his memory. The genius of Méryon continues, I think somewhat to obsess Cameron.'

Cameron and his critics establish him in the canon of western art while failing to acknowledge his indebtedness to Japanese prints. Clearly, this is a western-centric perspective, yet it also appears to be one of gender when his work is compared to that of his sister, Katharine.

Katharine and David Young Cameron were raised by a mother who was an amateur watercolourist, and both studied at the Glasgow School of Art, although David Young was the elder by nine years. Katherine became much more enmeshed with the Glasgow School artists, becoming part of a group of women artists who named themselves 'The Immortals'. Janet Aitken, Jessie Keppie, Margaret and Frances Macdonald and Agnes Raeburn were all part of this group.

As such, Katharine was perhaps more conversant with the avant-garde trends of the 1890s – including Dutch symbolism, the Celtic revival and Aubrey Beardsley – in addition to Japanese art. She was also among the first students under the direction of Francis Newbury, who added numerous design classes that had been traditionally associated with crafts to the curriculum of the Glasgow School of Art. It was this association with crafts, the Arts and Crafts movement and Japonisme (the western craze for Japanese art and design) that seemingly encouraged Katharine and other women artists to embrace the essence of Japanese art and not merely the formal elements.

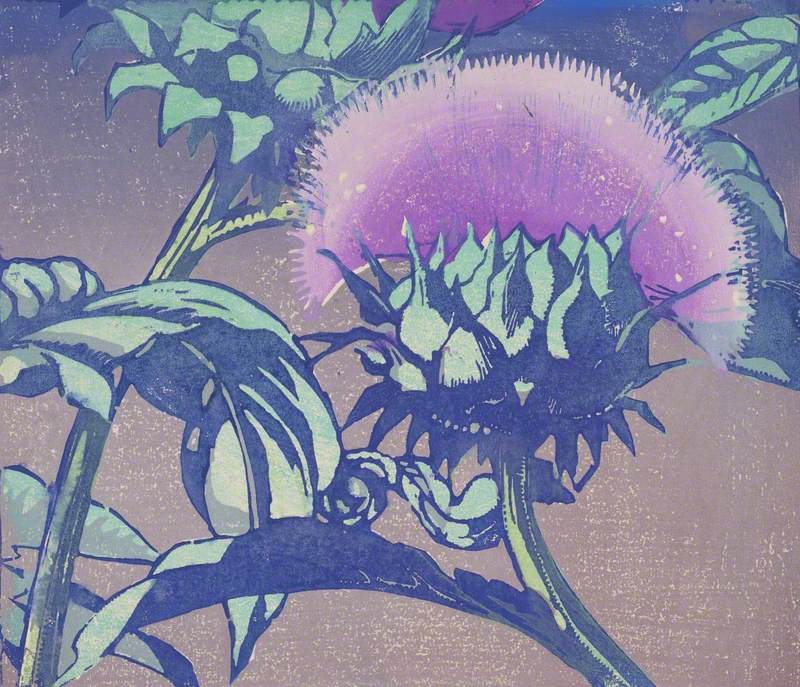

In stark contrast to her brother, contemporary critics repeatedly commented on Katharine Cameron's assimilation of Japanese art. The Glasgow Herald of 22nd September 1897 stated, 'Miss Cameron has modelled herself – wisely as it proves – on the Japanese method of arranging flowers for painting, of selecting and throwing her branch or spray of flowers across the paper.' The Evening Citizen of 8th December 1900 praised her 'flower studies of a Japanese character' and The Artist of February 1901 stated, that the 'minute accuracy' of her bees is only seen in the work of Japanese artists.

Critics were also careful to distinguish Katharine's works from those of her brother. The critic for The American Magazine of Art of 1919 wrote, 'Miss Cameron is the sister of the famous Scotch etcher, D. Y. Cameron, but no trace of the influence of her brother's style is found in her art. In most instances she chooses a single flower, or a single plant always as seen growing. Her treatment is naturalistic and at the same time exceedingly decorative.' Such reviews confirm that Katherine Cameron intentionally modelled her work on ukiyo-e prints unlike her brother, who borrowed from Japanese art yet asserted his allegiance to the western artistic canon.

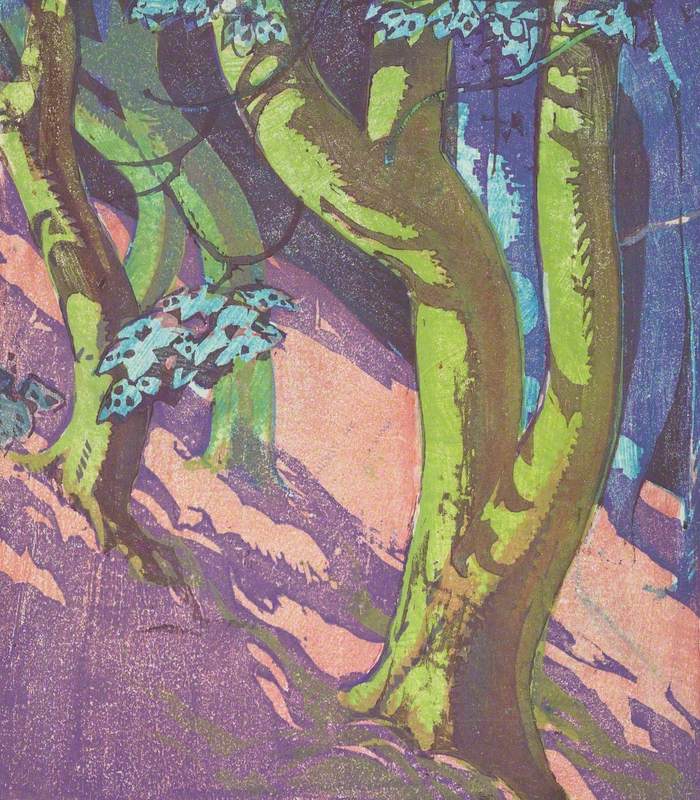

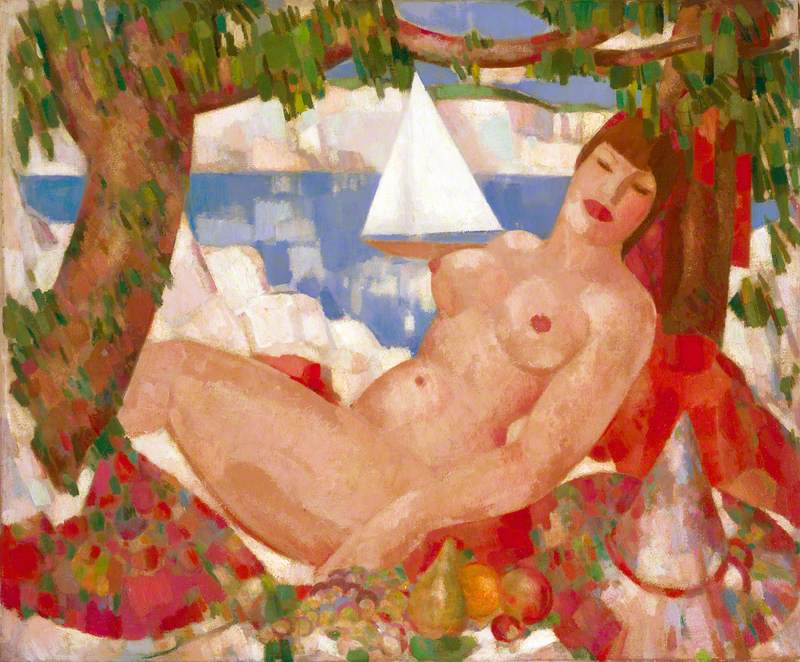

The same argument can be made for Mabel Royds, whose woodcuts have a stronger affinity to Japanese prints than those of her mentor Frank Morley Fletcher. Influenced by these prints, Royds created a forceful modernist sensibility by intensifying the use of repetitive patterns and heightening her colours. Unlike Morley Fletcher, Royds did not try to capture the British countryside in her prints, instead focussing as much on composition and design as the actual subject matter.

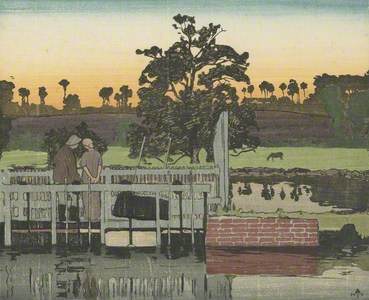

Plum Garden at Kameido (Kameido umeyashiki)

1857, woodblock print by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858)

Both Mabel Royds and Katharine Cameron were influenced by Japanese art in ways that the more traditional David Young Cameron and the less experimental Frank Morley Fletcher were not. They were among the early generation of women who were able to seek an art education, and although both enrolled in progressive institutions, they faced formidable barriers. They also both gravitated to the so-called graphic arts that were traditionally associated with women.

Additionally, Katharine Cameron enrolled in the Glasgow School of Art at a time when its director was actively adding classes on design and decorative arts. A critic in The Art Journal of 1896 asserted that women were doing 'the most excellent work in arts and crafts… It would be wiser if many who are trying to win positions as painters and sculptors were to direct their abilities into the less ambitious groove of applied art.'

It was not just their educations and the success of women in the Arts and Crafts movement that inspired Katharine Cameron and Mabel Royds to be open to a wider range of Japanese aesthetic choices than their male counterparts. Women printmakers were not tied to and were not part of the historic canon of western printmakers beginning with Rembrandt and Durer, and therefore they were less obliged to perpetuate that canon. This was in contrast to David Young Cameron – who looked to these artists – and Morley Fletcher who was tied to the British landscape.

Finally, Katharine Cameron and Mabel Royds felt confident that their works of floral subjects, traditionally associated with women, were especially suited to capturing a modernist aesthetic of abstracted naturalism, heavily rooted in Japanese prints.

Lindsay Leard-Coolidge, art historian