Roger Cecil might be the exemplar of an artist who, in that well-used phrase, is a ‘well-kept secret’.

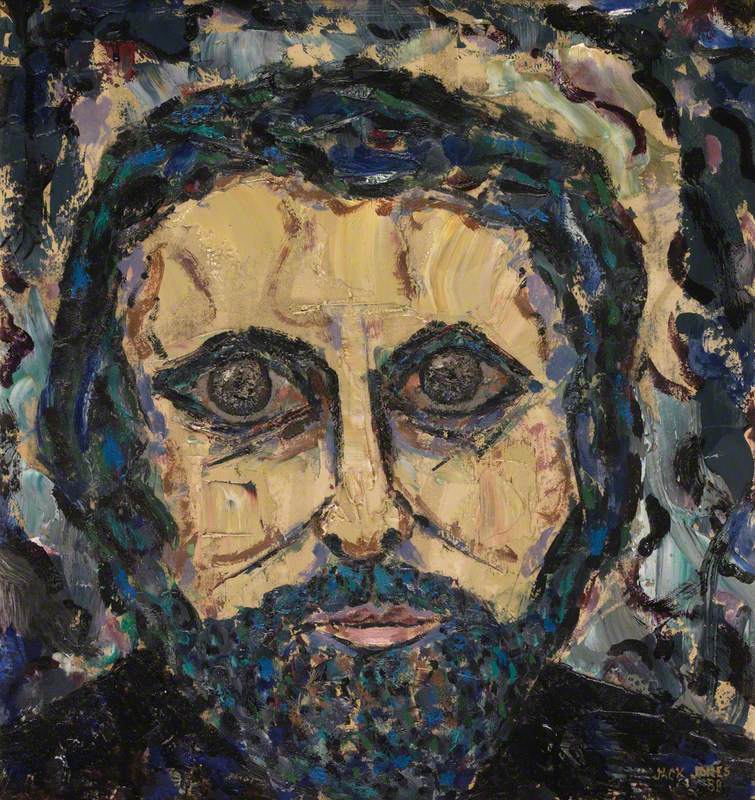

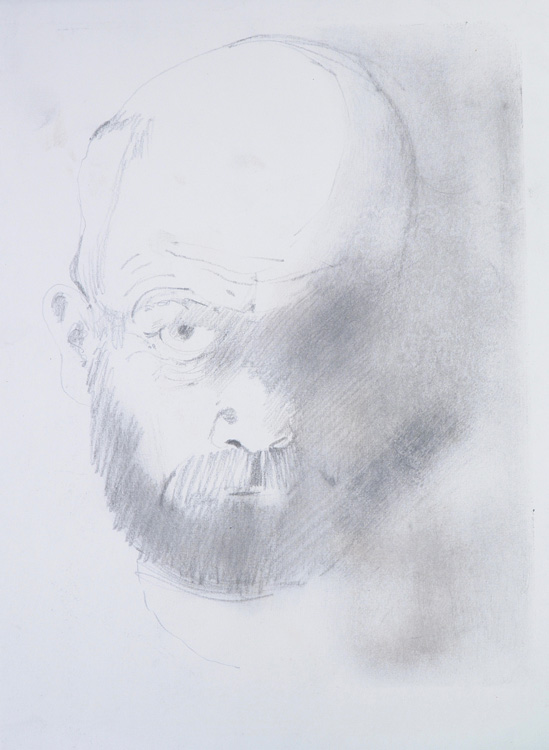

Self Portrait

c.1990, pencil on paper, 25 x 19cm by Roger Cecil (1942–2015)

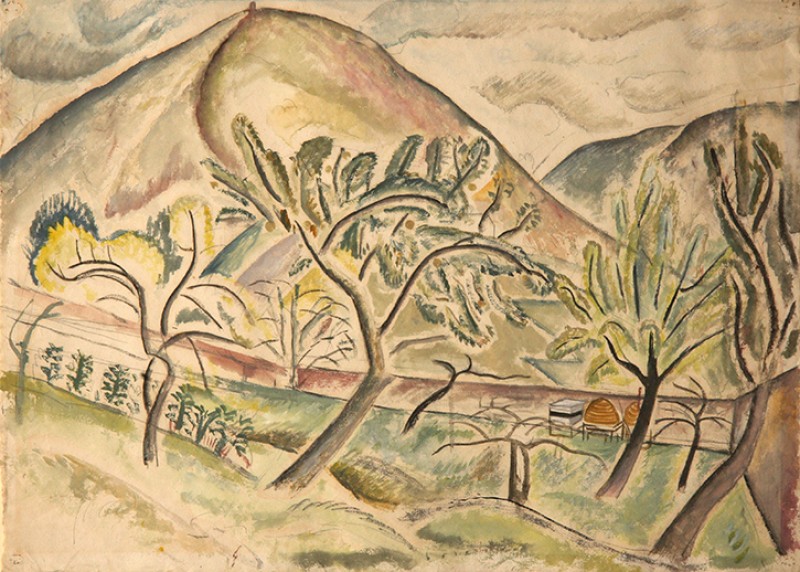

Looking at a painting like Summer Mist (2001), it’s not hard to see a serious talent at work.

David Buckman of the Dictionary of Artists in Britain since 1945 said, ‘In nine years of gathering material for a dictionary containing over 10,000 names, he remains the most impressive discovery.’ He was one of the

I first heard about Roger Cecil over 20 years ago. Artist friends who had got to know him told me he was something very special, a ‘great’ artist. I bought a little painting, which I loved, but he was elusive, never turning up at exhibition openings or other arts events. I was given his phone number and told the special code for getting him to answer – ring twice, ring off and then ring again – though I never quite found the reason for intruding on him.

After Roger died in 2015, I wrote his obituary for The Guardian and I saw a small memorial exhibition of works he had given to his friends over the years. It was a startlingly impressive show. Some months later I was invited to write a critical biography, now published by Sansom & Company as Roger Cecil: A Secret Artist, and to curate with his estate a substantial exhibition at MOMA Machynlleth, the public gallery with the largest collection of his works.

In some respects, Roger Cecil was far from secret. Many visitors came to visit him and talk about painting, for he was excellent company. Several galleries showed his work and usually sold it almost instantly to sharp-eyed collectors. Though it was commonly thought that he was poorly represented in public collections, I have discovered that nearly 20 of his paintings found their way to them.

Roger Cecil

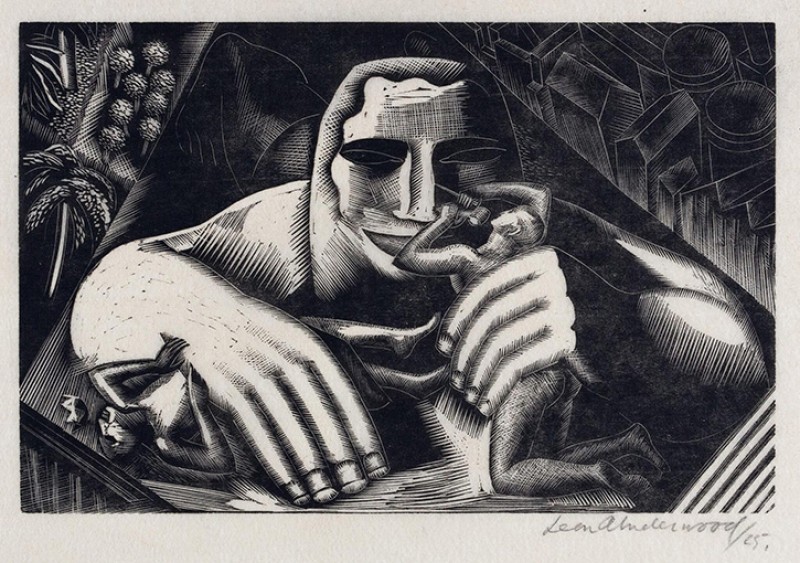

He was born into a mining family at Abertillery, deep in the South Wales coalfield, in 1942. Although he struggled at school, like many undiagnosed dyslexics, he wanted to be an artist from the age of 10 and he went to Newport College of Art when he was 15. Five years later he achieved the highest marks in the country in the National Diploma in Design. He won a prestigious scholarship to the Royal College of Art in 1963, but he walked out. He said he feared each student would become ‘a bit of everybody’ and he went home to Abertillery, ‘so I could do painting my way, and the way I felt it.’

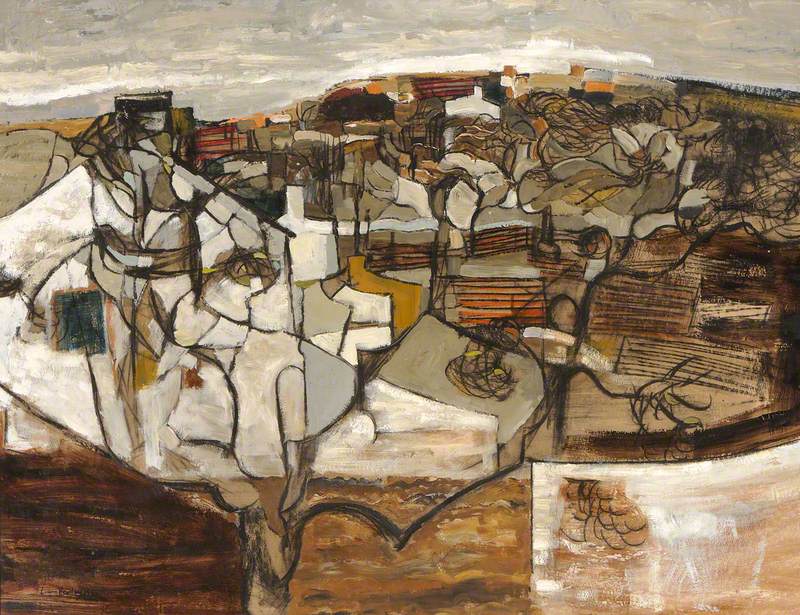

He used what materials he could afford: hardboard, household paints, plaster, grate-blacking. He quickly found his style: mostly abstract images grounded in landscapes and the human body and informed increasingly by mysticism. When his parents died he knocked together the main rooms of the house to make a bigger studio.

Though he avoided any overwhelming influence, he was widely read in European, African and Native American art and he digested ideas from many sources. The masterpieces he produced in his middle years were richly mysterious, recalling artists such as Antoni Tàpies, Alberto Burri and Jean Dubuffet, with whose work they could be exhibited in confidence. They sang with harmonies of greys, pinks, whites, deep brown and coal black, often erotically combining landforms with the human body. They were complex in texture – rough, dry, polished, pitted – and he worked the surfaces with decorating brushes, floats, chisels, sandpaper and tools of his own making. The marks were like the scars in his abused industrial landscape but they also brought to mind shamanic objects and hinted at concealed meanings. In Winter Night with Angharad (c.2003–2005), figures are merged with the landscape so that each can hardly be separated from the other. The board is covered in plaster that has been painted and polished. The pale shapes are excavated half a millimetre below the

The abstract form of Untitled I (c.1997) captures the qualities of his home valley. It seems to evoke the coal measures that underlie the landscape, the red of corrugated iron and the scars of quarries, tips and railways. He has given close attention to textures – burnishing some areas and leaving others matt, wrinkling the paint, scratching lines and punching marks.

What should a book and exhibition say about an artist who kept so much of his thinking to himself? Could poking into the artist’s mind be an intrusion or even a betrayal? Luckily, Roger said something on this topic in a BBC interview in 1964. Asked about how people might read his paintings he said, ‘I see it. That’s the trouble, it’s so personal,’ and went on to suggest a piece of text on the wall next to each picture to interpret it.

Most viewers need time to explore his paintings. He let forms and surfaces take on a life of their own. After seeing the Royal Academy’s Africa exhibition in 1995, he became fascinated with African art and the shaman, who he saw as paralleling the artist. A painting like Shaman Secret (c.1997) can be enjoyed as a purely abstract composition but it is full of motifs to wonder at. He wrote in 1997: ‘The artist/shaman is the one who manifests secrets to be decoded or interpreted by the viewer.’

The beauty would be enough but the mystery and magnetism of these fascinating, elegant, beguiling surfaces

In the work of many artists what you see is what you get. Looking longer, though repaid, seldom transforms anything. In the case of Roger Cecil, though, the seams beneath yield hidden riches.

Peter Wakelin, writer and curator

Roger Cecil: A Secret Artist (2017) by Peter Wakelin is available from Sansom & Company

‘Roger Cecil: Inside the Studio’ was at MOMA Machynlleth from 8 April to 24 June 2017