He’s still regarded as Scotland’s national poet more than two centuries after his death, and his birthday is celebrated every January at Burns Nights across the world – filled with haggis, pipes, poetry, songs and a generous helping of whisky.

But when a plan was hatched in 1812 to build a colossal national monument to Robert Burns and install it in the centre of Edinburgh, the money to fund it was not raised in

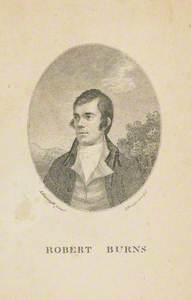

Robert Burns

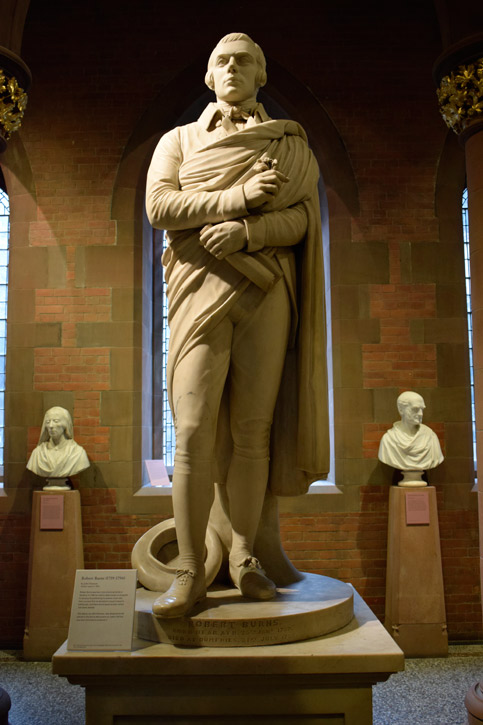

c.1826–c.1828, statue in white marble by John Flaxman (1755–1826) and Thomas Denman

The resulting work became the iconic sculptural portrait of the poet, but it was moved from place to place around the Scottish capital during the nineteenth century because of concerns that are still significant for public art today – conservation, pollution, financing and public accessibility.

In Bombay, it was John Forbes Mitchell of Thainstan who first came up with the idea to raise funds for a national monument to celebrate the Bard, who had died at Dumfries in 1796. Forbes Mitchell was a Scotsman, Burns enthusiast and merchant of the East India Company who was living and working in India, and in 1812 began a subscription scheme to fund a huge bronze statue in Edinburgh.

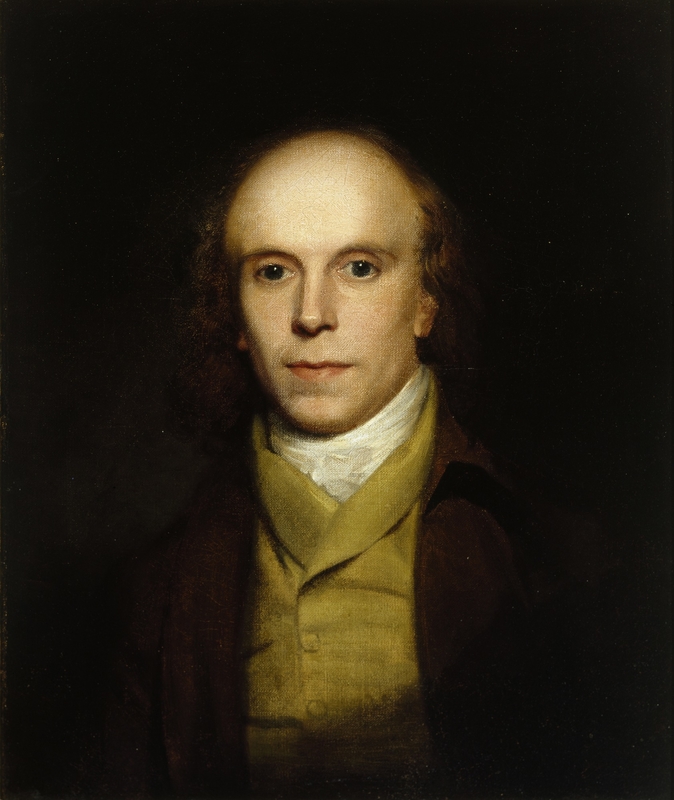

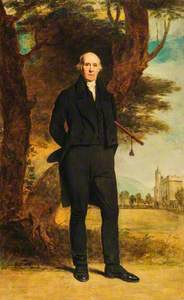

John (1755–1830), 4th Duke of Atholl, KT

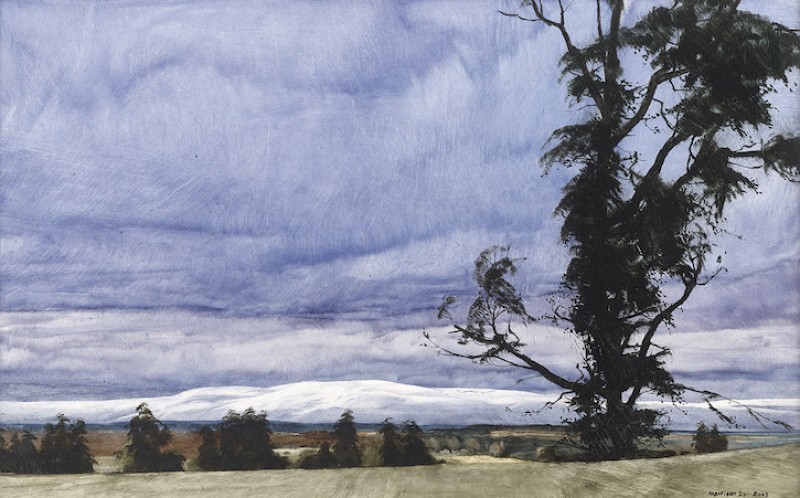

1901

Thomas Richard Hinks Beaumont (1857–1940)

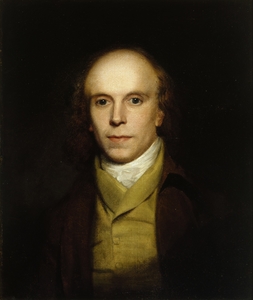

By 1819 more than £1,500 had been donated, and Forbes Mitchell travelled to London to discuss his plan with a group of aristocratic Burns enthusiasts. The meeting was supported by some highly influential figures – held in the Freemasons’ Tavern, it was chaired by the Duke of Atholl under the patronage of the Prince Regent, and those present formed a monument committee.

The plan was approved, but it was decided that a life-size marble sculpture would be a more suitable memorial, to be housed in one of the Scottish capital’s fine buildings – preferably the university library. In 1824 the committee commissioned John Flaxman, the most famous British sculptor of his day, and by then nearly 70 years old, to do the work for an agreed fee of £1,400, though he had offered to do it for nothing.

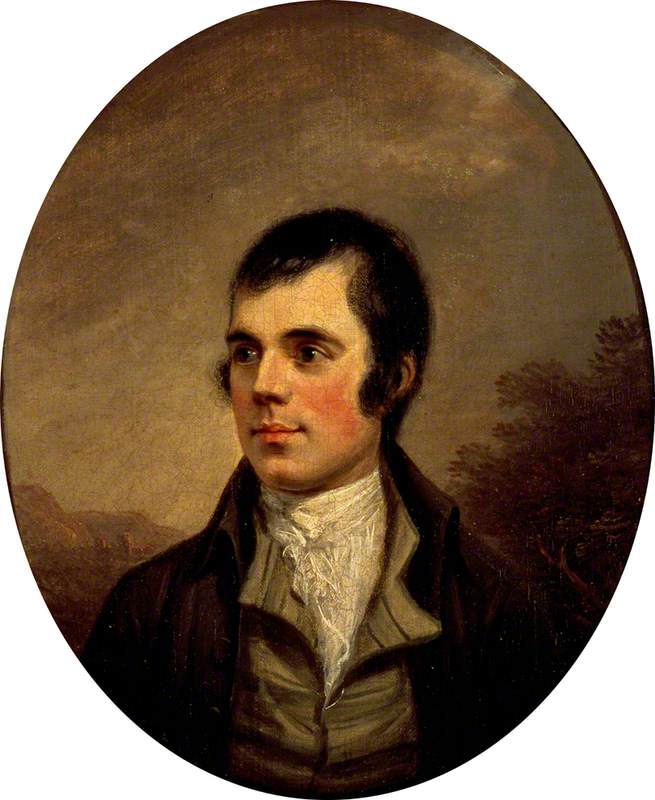

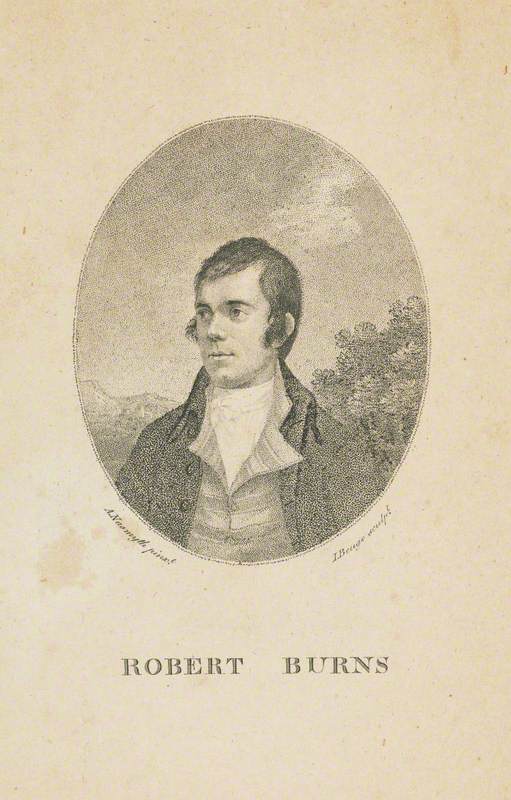

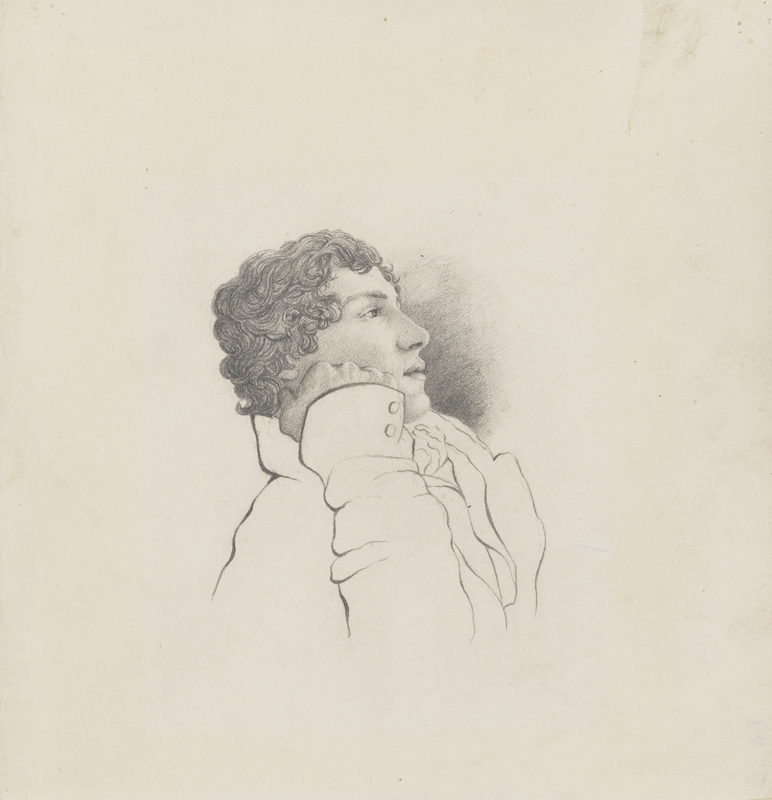

In order to create a good likeness, Flaxman was sent the oil portrait of Burns painted by Alexander Nasmyth in 1787, as well as an etching by John Beugo. Nasmyth had been a good friend of Burns, and the poet’s son had confirmed the painting looked a lot like him (it is now on display in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery). It shows the poet aged just 28, was painted from

Jean Armour (1765–1834), Mrs Robert Burns

1822

John Alexander Gilfillan (1793–1864)

George Thomson (1757–1851), Collector of Scottish Songs

Henry Raeburn (1756–1823) (after)

The painting was procured from Burns’ wife, Jean Armour, by George Thomson, Burns’ friend and publisher, who sat on the monument committee. Thomson later wrote:

'For enabling him [Flaxman] to transmit the features of the poet to posterity as faithfully as possible, I obtained from Mrs Burns, and sent him the portrait in oil painted from life very successfully by Mr Alexander Nasmyth, Edinburgh, being the only portrait for which he ever sat to any reputable artist, as far as I know: and, along with it, I sent the small engraving done from it by Beugo for the first Edinburgh edition of his [Burns’] poems; for Mr Beugo told me that he was frequently visited by Burns while at work on the plate, and thus had opportunities of examining his manly expressive countenance when lighted up by conversation: and though I recommended the painting to Mr Flaxman as his safest guide to likeness, I did not think it right to withhold the engraving, nor to omit

Robert Burns

c.1826–c.1828, statue in white marble by John Flaxman (1755–1826) and Thomas Denman

Flaxman worked on the sculpture depicting the poet in a standing pose, reciting his poem To a Mountain Daisy. He reported on his progress to George Thomson in 1826: 'The marble is very good tho’ not absolutely spotless. I am very glad it is to be placed in the Library of the University not only because the situation is noble but because it is

In December that year, before the work could be completed, Flaxman died, and along with many of the artist’s other unfinished works, the sculpture was completed by his brother-in-law and pupil, Thomas Denham.

By the time the work was finished, the funds raised had increased to more than £3,000, so with the remainder of the money the committee decided to construct a monumental 'temple' to house the sculpture, and instructed the Greek-revivalist architect Thomas Hamilton, who had designed the Burns Monument in Alloway.

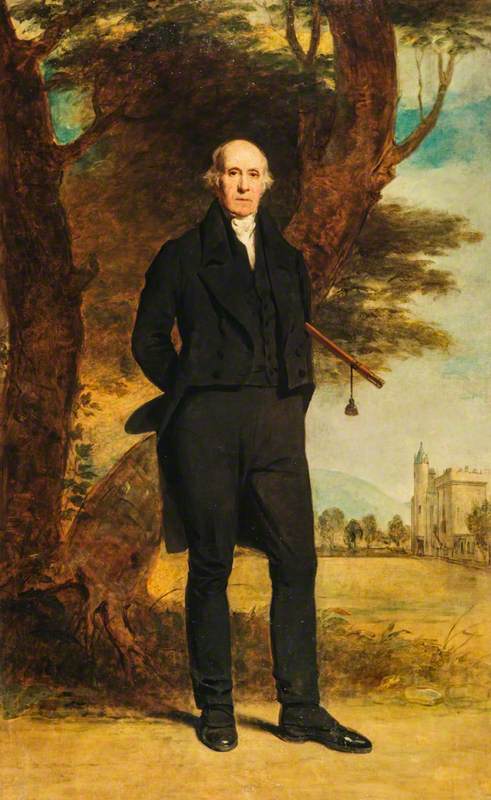

Henry Thomas (1779–1854), Lord Cockburn, Judge and Author

c.1835

John Watson Gordon (1788–1864)

The foundation stone was laid in 1831, but right from the start there were concerns about its location at the bottom of Calton Hill – it was close to foundries, breweries and gas works, and by 1836 George Thomson and notable Edinburgh figures including Lord Henry Cockburn, the judge and architectural conservationist, were suggesting it should be moved – partly because somebody had to be paid to look after it, so the public had to pay to see it.

Thomson wrote of the sculpture’s blackened appearance, and expressed his concern that Flaxman’s work would be 'despoiled of its brightness and purity'. He argued that it should be

At that time Scotland had no national gallery or portrait gallery – which would have been the obvious choice otherwise. 'The Committee therefore are fully convinced that they shall better discharge their duty and much more effectually provide for the permanent safety of this fine work of art, by having it placed in one of the most respectable public institutions in Edinburgh, since we have as yet no Pantheon or National Edifice for the reception of the Statues and Busts of eminent Scotsmen.'

Thomson’s plea was backed up by Lord Cockburn, who said that to 'shut up Burns in a Box and let people get a glimpse of him by opening a locked door and then closing it on him is an outrage on all

In 1846, the statue was handed into the care of Edinburgh Corporation, now

Robert Burns

c.1826–c.1828, statue in white marble by John Flaxman (1755–1826) and Thomas Denman

The statue stayed in the library until 1861, when it was moved to the recently opened National Gallery of Scotland, a location it was hoped was more accessible to the public. It stayed there until

In 2017 Douglas Gordon, the Turner Prize-winning artist, used the work as part of his installation for the Edinburgh Art Festival, questioning the depiction of Burns in the sculpture as a national hero. For Black Burns, Gordon used black marble to create a replica statue, which he then shattered and displayed on the floor of the gallery at the foot of Flaxman’s sculpture.

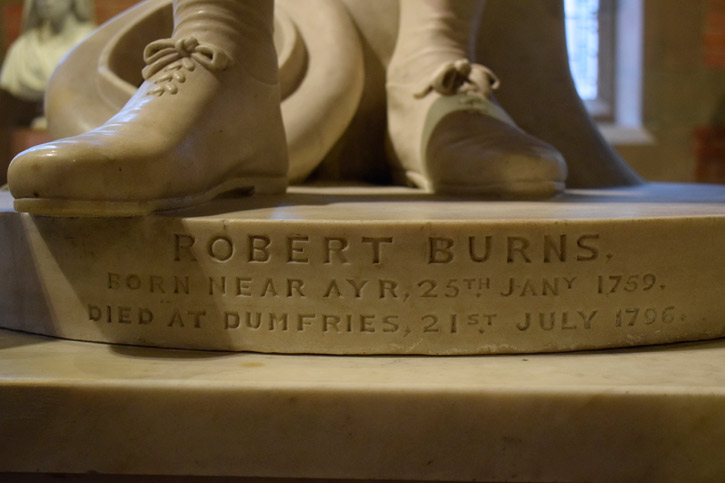

Robert Burns

(inscription), c.1826–c.1828, statue in white marble by John Flaxman (1755–1826) and Thomas Denman

The Flaxman sculpture bears the simple inscription 'Robert Burns / Born Near Ayr, 25th Jany 1759. Died at Dumfries, 21st July 1796.' When the sculpture was completed, George Thomson wrote to Sir Walter Scott to ask him to write an inscription for the work. His reply was simple: 'Give the name of the Poet. Who does not know the rest?'

Rhona Taylor, Coordinator for Art UK's Sculpture Project

Thanks to Imogen Gibbon, deputy director of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Becky Howell, archivist at the National Galleries of Scotland, and Helen Scott, curator at the City of Edinburgh Council.