Reframing the Wild explores the relationships between humans, animals, and art, drawing on various art objects to demonstrate how humans have shaped understandings of the natural world through art. From the eighteenth century, imperialism, industrialisation and scientific developments transformed, challenged, and threatened relationships between humans and animals. This exhibition aims to provoke viewers to consider the ways in which wildlife exists only as defined by humans.

Reframing the Wild took place at Wolverhampton Art Gallery in 2019, curated by Dr Kate Nichols, Fellow of the University of Birmingham's Department of Art History, and Dr Samuel Shaw, Teaching Fellow in Nineteenth Century Art at the University of Leicester.

What is wildlife?

Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was first published in 1859 and radically changed the perceptions that many people had regarding human-animal relationships. The idea that humans were closely related to, or even were, animals, was taken seriously for the first time. However, the notion that humans and animals form separate categories persists, as does the idea that some animals remain essentially ‘wild’ or ‘exotic’, while others are essentially ‘tame’ or ‘domesticated’.

And yet what does it mean to be truly ‘wild’ in the world today? Is wildness something that can be accommodated into our daily lives, as zoos promise to do, and if so at what cost? In this section we explore these questions through a range of artwork.

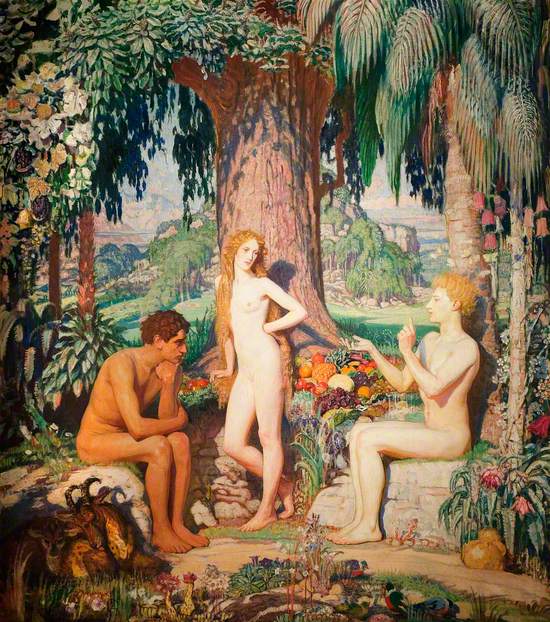

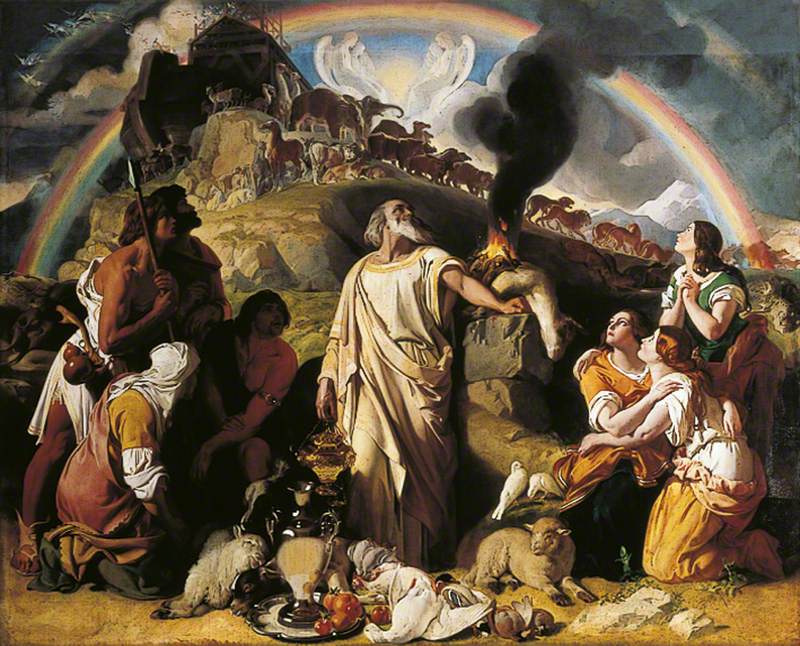

The Creation

In the Jewish and Christian narrative of the Creation, humans are clearly separated from other animals: a distinction that has formed the basis of human-animal relations in western society for many centuries.

This colourful rendering of the Garden of Eden depicts Adam and Eve in conversation with the Archangel Raphael, surrounded by fruit, birds and – at the bottom left – a pair of goats. The snake, on which the next stage of the story turns, is not yet in sight.

George Spencer Watson (1869–1934)

Oil on canvas

H 162 x W 142 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

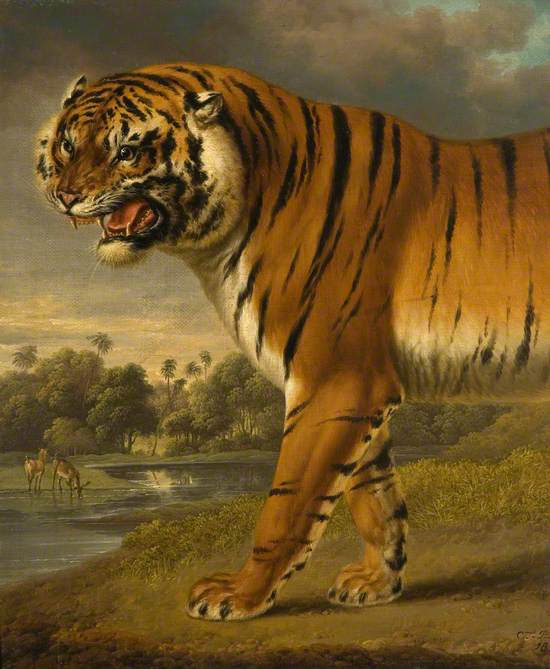

A Tiger

Towne painted this apparently wild creature from either a captive animal in a menagerie, or from a taxidermied (stuffed) specimen. Today we think of tigers as beautiful, but in the 1800s they were considered to be uniquely blood-thirsty. This reputation made them especially prized hunting trophies. In the context of British colonial involvement in South Asia, their supposed viciousness was also associated with what Europeans viewed as the ‘wildness’ of the Indian subcontinent.

Charles Towne (1781–1854)

Oil on panel

H 33.5 x W 22 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

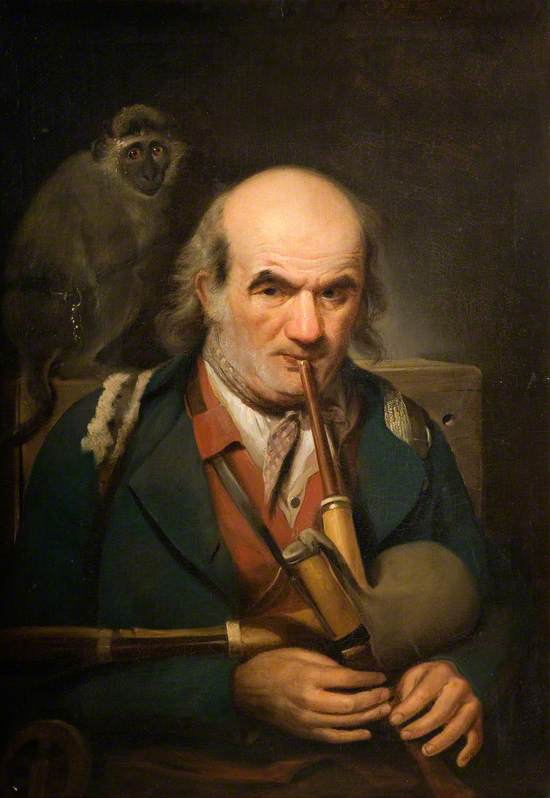

Italian Dancing-Dog Master

Travelling menageries, collections of captive animals kept for display, and entertainers provided the main means for people to encounter ‘wild’ animals in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain.

This musician is accompanied by a small, chained monkey – possibly a vervet, still used in circuses – who sits near his shoulder, inviting comparison between the two faces. Animals also feature via the man’s bagpipes, which would have been made from the skins of goats or lambs. The stocks of a bagpipe were traditionally inserted where the limbs and head of the animal would have been.

Edward Bird (1772–1819)

Oil on canvas

H 91.5 x W 63.5 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Everyday wildlife

Most of the animals that appear in our collection are not ‘exotic’ but ‘everyday’. In the nineteenth century animals were a major feature of daily life, either as part of the workforce or as pets. Industrialisation increased the number of animals working in cities and the countryside. The practice of keeping animals for companionship and amusement also spread beyond the aristocracy. The Victorian pet craze was a way of taming the wildness of nature, making animals safe and domestic.

Animals also entered our culture in other ways, playing symbolic roles in shifting ideas of family life, or reflecting ideals of masculinity and femininity. This section features representations of animals in agricultural, domestic and industrial contexts.

St Valentine's Morning

A luxuriously dressed young woman admires herself in the mirror as she reads a Valentine’s letter. She is accompanied by a lap dog, who is eating a discarded note. Woman and dog are allied here, and their similarly lustrous, curly hair emphasises their connection. The dog might even be seen as the victorious suitor!

John Callcott Horsley (1817–1903)

Oil on canvas

H 59.5 x W 71.5 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Love me, Love my Dog

Pets blur the human-animal divide. Unlike working animals, they live in our homes and are often regarded as family members. Pets and children were frequently associated with each other in Victorian culture and regularly appear together in artworks.

Dogs were often seen as the ideal child: obedient, malleable and, importantly, forever young. Here, child and dog appear as an inseparable double-act.

Charles Baxter (1809–1879)

Oil on board

H 26 x W 22 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

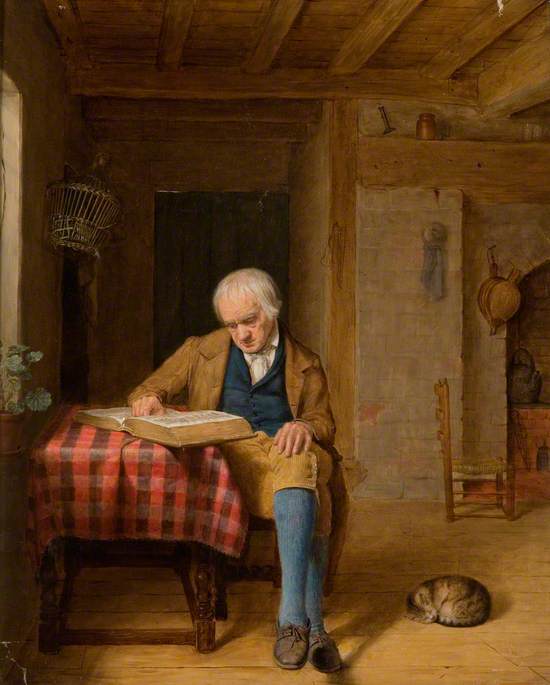

Sunday Afternoon

Sitting at a table in a sparsely decorated room, an elderly man quietly reads the Bible in the company of his sleeping cat.

This humble scene suggests how the nineteenth-century idea of the pet could reinterpret animals which were often seen as vicious and brutal. The cat appears as a peaceful – perhaps even spiritual – domestic companion.

Edward Thompson Davis (1833–1867)

Oil on canvas

H 72.5 x W 42 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

The Pet Bird

This painting questions the distinction between humans and animals. Who exactly is the Pet Bird of the title here: the woman leaning out of an enclosed dark interior, or the bird who appears to have just landed on her hand?

In Victorian literature and art, women were often compared to pets in general (domestic and apparently helpless), but especially to songbirds (musical, caged, decorative).

Daniel Maclise (1806–1870)

Oil on canvas

H 92 x W 70.6 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Waiting

Though most of us think of dogs as pets – ‘man’s best friend’ – their close association with humans comes out of their role as workers. Dogs have traditionally mediated between humans and other animals: helping herd sheep, leading the hunt, or controlling vermin.

Unsurprisingly, dogs appear in more paintings than any other animal. George Armfield forged an entire career painting them.

George Armfield (1810–1893)

Oil on canvas

H 51 x W 61 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

A Prize Bull

Nineteenth-century paintings of prize bulls – often portraits of famous individuals, or rare breeds – are common, though Edmund Bristow’s representation is unusual in managing to create a palpable sense of drama.

Storm clouds gather behind the bull, almost as if the huge animal has the ability to summon bad weather. This marks the painting as part of the Romantic movement, which saw nature as a raw, sometimes uncontrollable, force.

Edmund Bristow (1787–1876)

Oil on canvas

H 61.5 x W 77 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

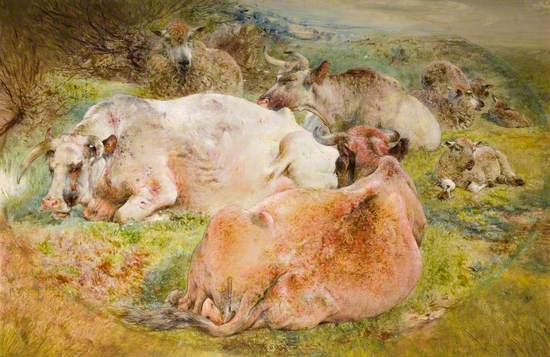

Cattle and Sheep

William Huggins was a very well-respected animal painter, whose repertoire included lions and tigers as well as cows and sheep. He is known to have visited menageries and zoos regularly, as well as keeping animals at home.

Huggins once described himself as ‘a just and compassionate man who would neither tread on a worm, nor cringe to an Emperor’. His paintings are remarkable for the detailed attention paid to the animal’s skin, as well as the high horizons, which create the sense of an animal’s eye-view.

William Huggins (1820–1884)

Oil on board

H 34 x W 49.5 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

A Girl with Two Calves

The realities of farm-work in Victorian Britain were rarely as delightful as this sunny painting suggests. Wages were low, living conditions were poor and many children started work at the age of six. In the last few decades of the nineteenth-century, when this painting was made, the situation was worsened by the agricultural depression. Farms with only a small number of animals faced a particular struggle for survival.

Walter Hunt (1861–1941)

Oil on canvas

H 114.5 x W 77 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Girl with Two Cows

In comparison to Walter Hunt’s A Girl with Two Calves, Giffard Lenfesty’s representation of a female farmworker aims for a greater degree of realism, and may have been based on a scene he witnessed first-hand. He pushes the action into the background of his painting, and poses the woman in a way that suggests she is not especially enjoying her role. In Victorian animal paintings, we are used to seeing animals pictured from the side, or the front. Lenfesty surprises us, perhaps, by offering us the cow’s rear-end.

Giffard Hocart Lenfestey (1872–1943)

Oil on canvas

H 61 x W 76 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Feeding the Chicks

Like the Hunt brothers, John Linnell frequently painted pastoral scenes featuring young children and animals. In this painting, a direct connection is made between the mother hen and her chicks, and the human woman and her children. The difference is that the hen is trapped in a wicker cage.

The theme of the caged bird – representing repressed freedom – was a very popular one in Victorian art.

John Linnell (1792–1882)

Oil on canvas

H 26 x W 32.5 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Four Sheep

Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803–1902)

Oil on panel

H 45 x W 35 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Landscape with Cattle and Fowl

Thomas Cooper was known by fellow artists as ‘Cow Cooper’. There are almost two hundred of Cooper’s cow and sheep paintings in public ownership in the UK, many of which contain the same groups of animals represented in slightly different settings. There are rarely any people or buildings in his pictures. His visions of docile farm animals situated in rural landscapes refer back to an idealised image of pre-industrial England.

Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803–1902)

Oil on canvas

H 42.5 x W 53.5 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Waiting to be Fed

Edgar Hunt (1876–1953)

Oil on canvas

H 61 x W 45.5 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

The Donkey

The brothers Walter and Edgar Hunt were part of a Warwickshire-based family of animal painters who profited from the Victorian fashion for sentimental farmyard pictures. Their vision of rural life was a highly idealised one, often using animals to reinforce conservative ideas about male and female behaviour, or to allude to the Bible. The donkey in Walter’s portrait, for example, is surely intended to remind us of the donkey that was present at the birth of Christ, or which carried him into Jerusalem.

Walter Hunt (1861–1941)

Oil on canvas

H 30.5 x W 40.5 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Not wild, not alive

Animal products form the very basis of art, from insects crushed to make pigments, ivory used in sculpture, badger, stoat, squirrel, bear, camel and horse hair in paint brushes, to egg used to bind paint. The physical properties of these materials are fundamental to an artwork’s appearance. So, are all works of art animal artworks, even those that do not depict animals? Should we acknowledge animals as contributors to the art world? Are all visual representations of wildlife compromised by the fact that they are made of animal products?

In this section are artworks selected to highlight the violent transformation of animals into commodities, and to consider the contribution animals make to art.

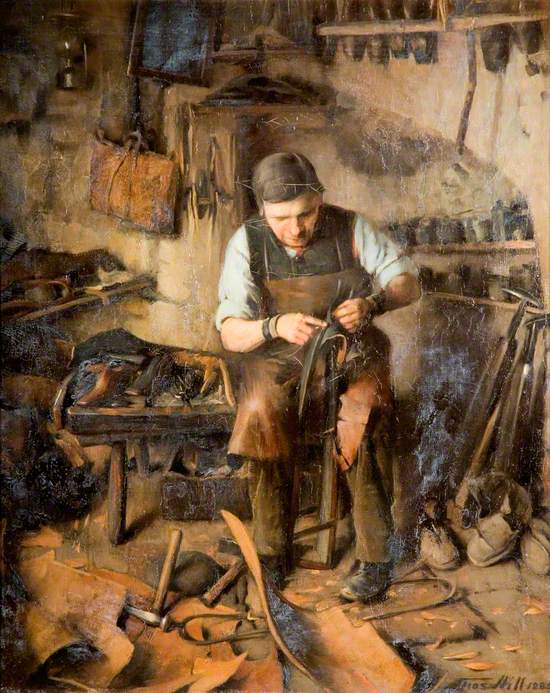

The Village Cobbler (Codsall)

Leather products dominate this overwhelmingly brown-coloured painting. It makes an interesting comparison with contemporary idealistic images of cows freely roaming hillsides, some of which can be seen in the ‘Everyday Wildlife’ section above. A Victorian viewer might have been more alert than we are to the animal origins of such products. Tanneries, where leather was made, were located close to slaughterhouses, and herds of cows being driven to slaughterhouses were a regular feature of the nineteenth-century town.

Thomas Hill (active 1878–1913)

Oil on canvas

H 49.3 x W 39.4 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

The Silken Gown

It is easy to overlook representations of animal products in artworks. Yet the entire drama of this image, based on a Scottish ballad, revolves around the luxurious silk gown at its centre, a marked contrast with its drab surroundings. Thousands of silkworms, in tandem with intensive human labour, are required to produce the raw material for such a garment. Should we consider the contribution made by combined insect and human labour to such artworks?

Thomas Faed (1825–1900)

Oil on canvas

H 76 x W 63.5 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

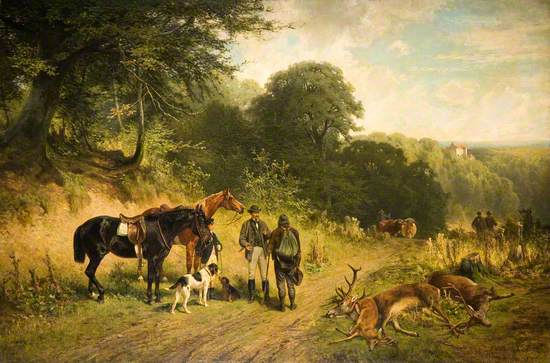

A Good Day

Working-class blood sports such as cock-fighting, dog-fighting and bear-baiting were banned in England by the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1835. Aristocratic blood sports, especially fox and deer hunting, however, were as popular as ever and widely celebrated in visual culture.

This canvas by German-born Friedrich Johann Voltz probably depicts a hunt in his native Bavaria, reminding us of the popularity of hunting throughout Europe. A ‘good day’ for the hunters and working animal is obviously not such a good one for the unfortunate deer.

Friedrich Voltz (1817–1886)

Oil on canvas

H 80.5 x W 124 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Still Life with Dead Duck

Still life paintings have often featured dead animals. They were particularly common in Northern Europe from the seventeenth-century onwards. Rembrandt famously painted the carcass of a slaughtered ox, and they find modern counterparts in the work of artists such as Joseph Beuys, Helen Chadwick, and Damien Hirst.

Despite the underlying violence of images such as this one, dominated by a dead mallard, they are often curiously bloodless affairs.

William Davis (1812–1873)

Oil on canvas

H 76 x W 61.5 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

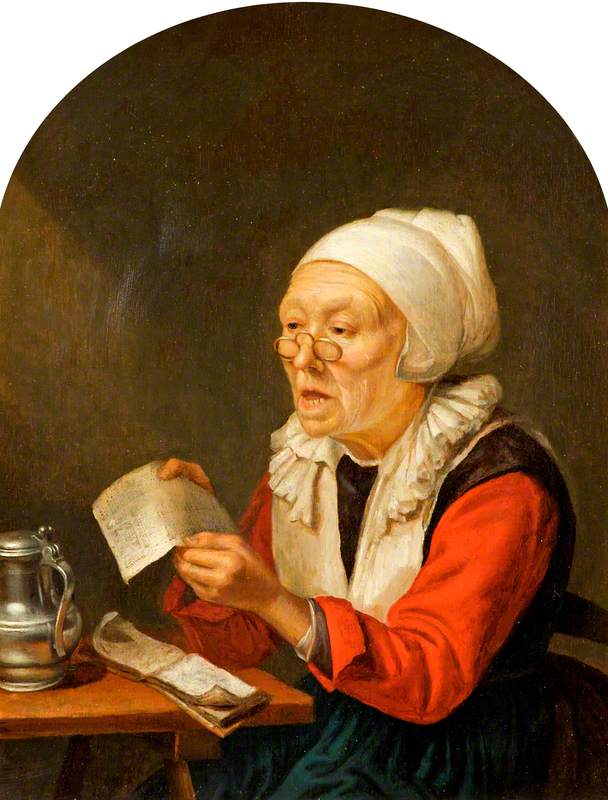

Grace before Meal

Like many seventeenth-century Dutch genre paintings, this work focusses on the everyday life of the working classes. The meat that the elderly woman is giving thanks for may not be something she regularly enjoys, and the ritual of saying grace may serve to remind her that meat should be considered a divine gift rather a human right. This idea is reflected in the work’s alternative title: Grace before Meat.

Our complex attitudes to meat in the West are underlined by the fact that the other animal present in this painting – a small white dog – would never be considered as a potential dinner.

Gerrit Dou (1613–1675) (after)

Oil on panel

H 24.8 x W 20.3 cm

Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Animal materials

Most artworks contain some animal products. Many ornamental objects and tools in our collection not only represent animals but are made primarily from animal body parts. The animal materials from which they are made contribute towards their appearance. Ivory, for example, is dense, easily carved, and lends itself to detailed engraving.

This section additionally highlights the importance of working animals in industrial trades. In coal mines across the country, including in the West Midlands, pit ponies hauled tonnes of coal along underground railways. They were first introduced in an attempt to replace women and children under-ten working in the mines and became a vital part of the industry. The last working pit pony retired in 1999.

.

Leading the Barge Pony

Leading the Barge Pony | Edwin Butler Bayliss | c.1900-45 | Watercolour with pastel on paper

Wolverhampton artist Edwin Butler Bayliss was well known for his early-twentieth-century images of local industry. Horses seldom feature in Bayliss’ work, but they played a fundamental role locally, especially in transporting produce.

This watercolour shows a woman leading a barge pony at the end of a day’s labour. They seem equally exhausted, with strides matching as they lean into each other in a comfortable, intimate way: their working lives closely intertwined.

Leading The Barge Pony

Explore artists in this Curation

View all 20-

William Davis (1812–1873)

William Davis (1812–1873) -

William Huggins (1820–1884)

William Huggins (1820–1884) -

Daniel Maclise (1806–1870)

Daniel Maclise (1806–1870) -

Edward Thompson Davis (1833–1867)

Edward Thompson Davis (1833–1867) -

Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803–1902)

Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803–1902) -

Thomas Hill

Thomas Hill -

George Spencer Watson (1869–1934)

George Spencer Watson (1869–1934) -

Gerrit Dou (1613–1675)

Gerrit Dou (1613–1675) -

Giffard Hocart Lenfestey (1872–1943)

Giffard Hocart Lenfestey (1872–1943) -

John Callcott Horsley (1817–1903)

John Callcott Horsley (1817–1903) - View all 20