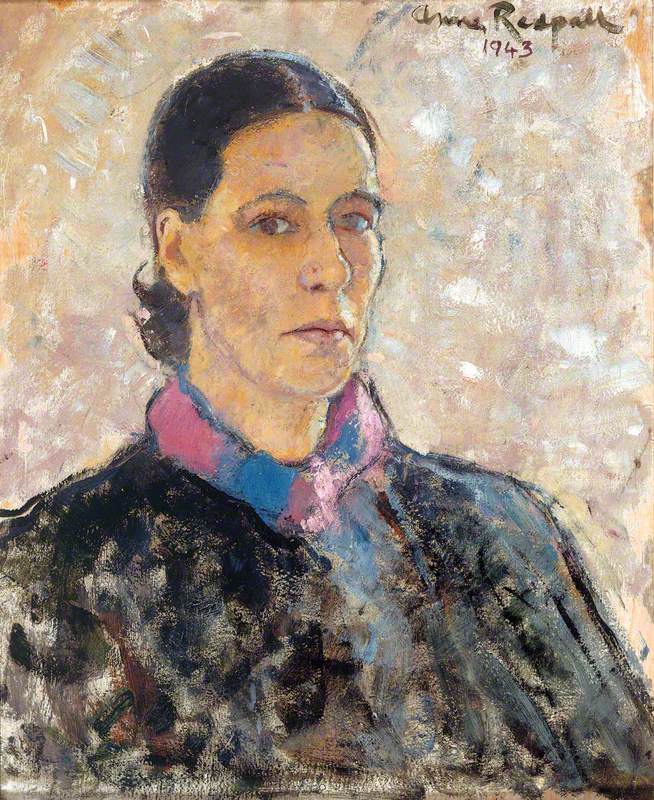

Stacks of plastic buckets, piles of old rope and industrial wastelands don't seem very promising as starting points for painting. But for artist Prunella Clough (1919–1999) the objects, buildings, and even the empty spaces that most of us walk past without a second glance, were rich sources of inspiration.

Colour photograph of a stall called 'The Tool Shed' selling plastic buckets and spades

1990s, photograph by Prunella Clough (1919–1999)

Early inspiration: Lowestoft and Aldeburgh

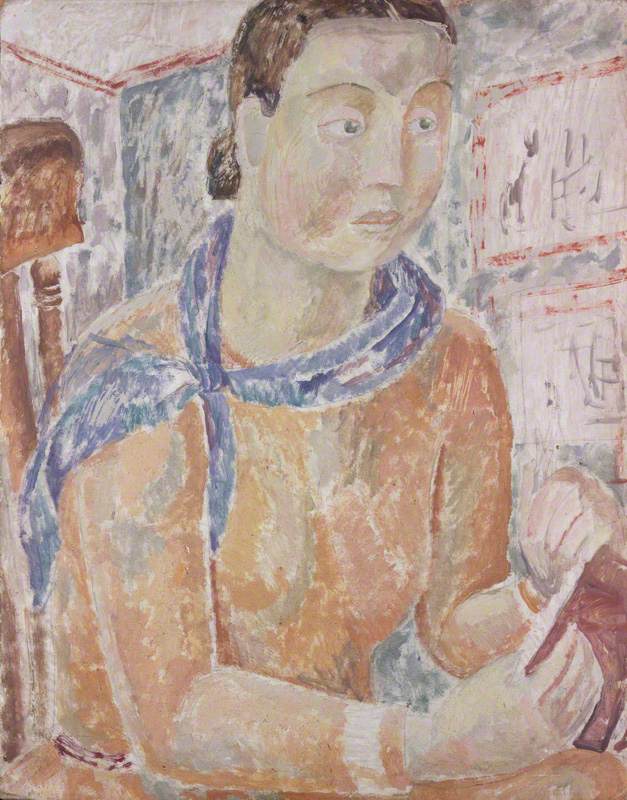

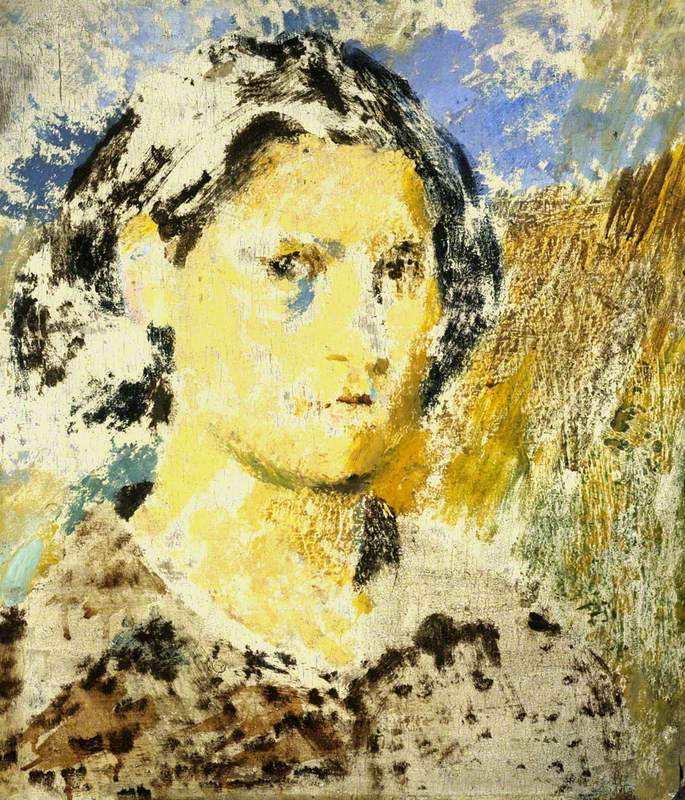

Clough was born in 1919 in Knightsbridge, London to a wealthy family with aristocratic connections (though she insisted to her friends that they were 'very minor' aristocrats). She enrolled at Chelsea School of Art in 1937 and studied there until the outbreak of the Second World War.

Despite Clough's privileged upbringing (or perhaps because of it), she sought out the ordinary every day. Her family holidayed regularly in Southwold in Suffolk in the 1940s, and she was drawn to the bustle of the nearby ports of Aldeburgh and Lowestoft. She painted fishermen, dockworkers and lorry drivers surrounded by fishing sheds, boats, nets, floats and boxes of fish.

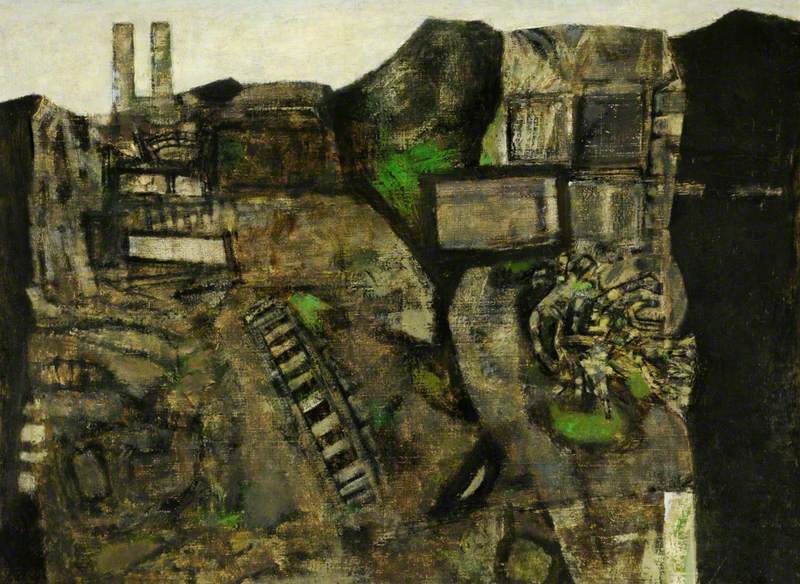

Industrial places and workers

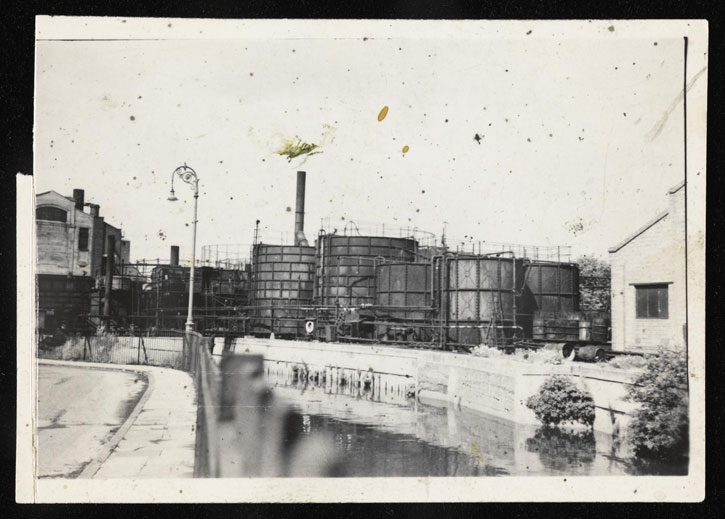

In the 1950s Clough turned her attention to industrial buildings and workers and the often-overlooked edges of cities where factories dwindle to wasteland.

Notes and sketches map her visits to the Midlands, the North of England and London – where she explored Wapping, Rotherhithe, Battersea power station, Fulham gas works, and cooling towers at Canning Town.

Although her focus at this time was on the industrial workers, the composition and atmosphere of her paintings are very much defined by the shapes, structures and textures of the buildings and objects that frame the figures. The art critic John Berger, a close friend, encouraged her interest in capturing the realism of these industrial scenes.

Black-and-white photograph of a canal and gas works

1950s, photograph by Prunella Clough (1919–1999)

Berger once wrote: 'She looks out on an industrial city – its greased axles, its riveted plates, its plane boars, its cables, ladders and tarpaulins, its rust, its crude protective paints, the condensation of its atmosphere – allows the very fabric of it to press in upon her imagination, and then tries to find, in terms of paint, the equivalent of its imprint.'

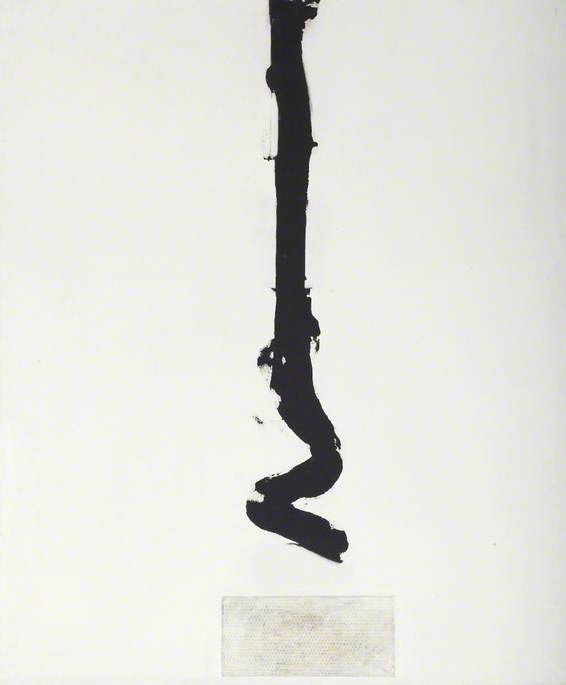

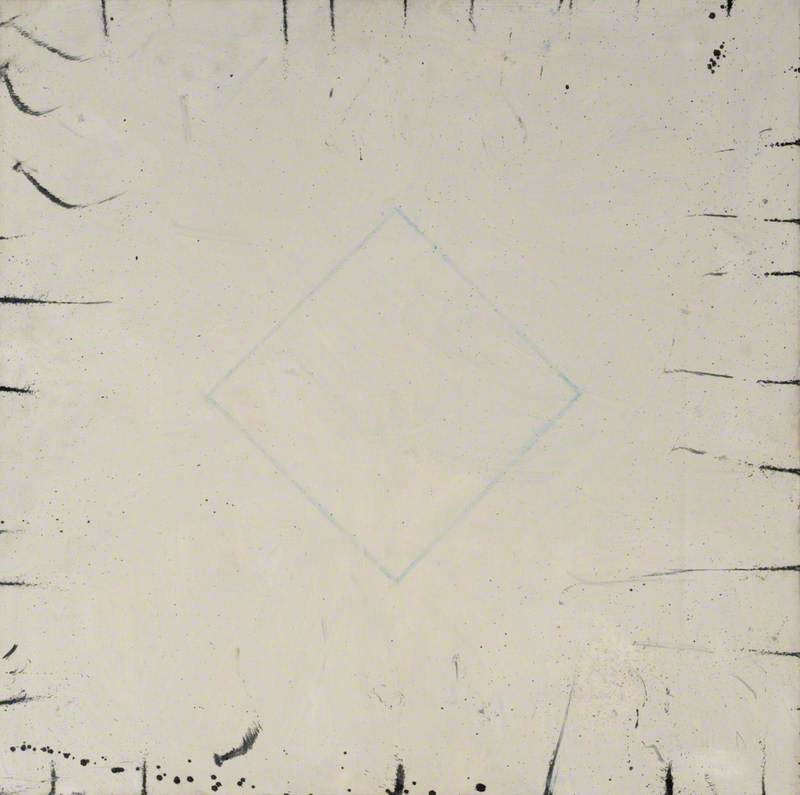

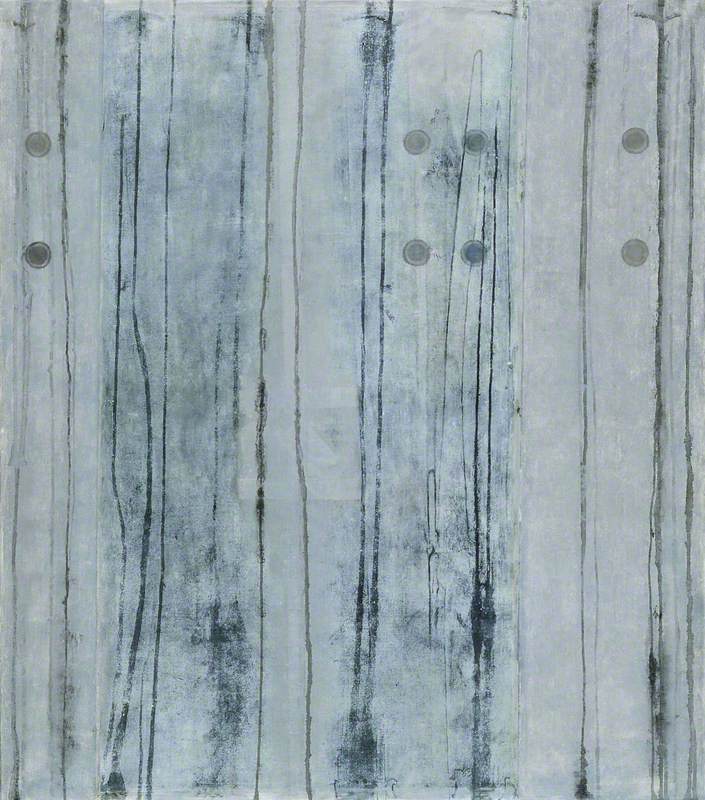

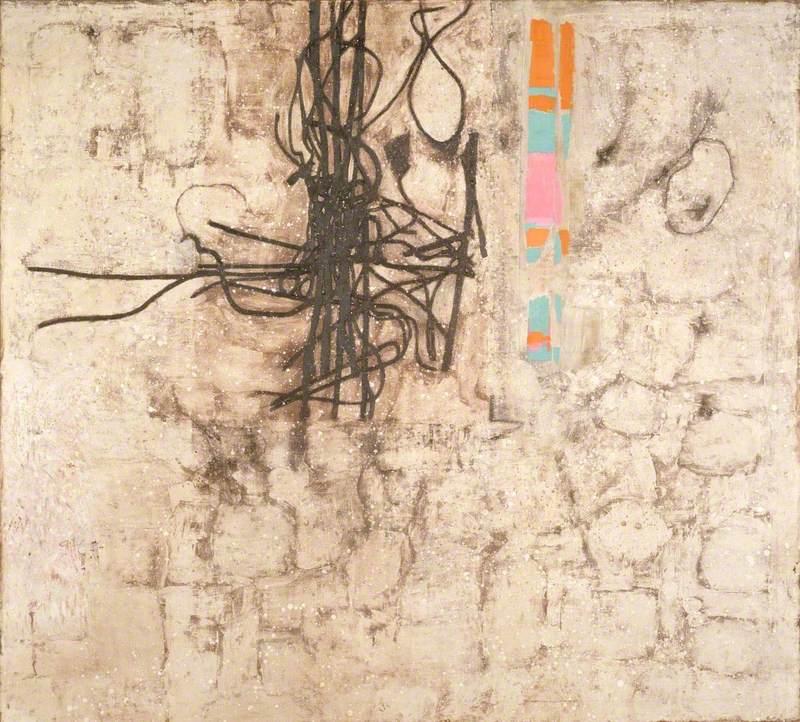

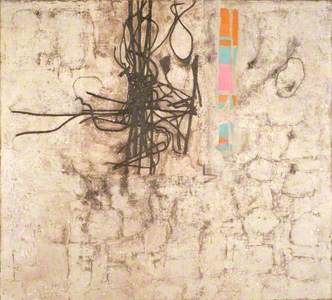

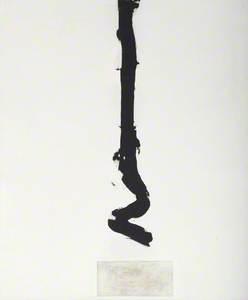

Abstracting the real

In the late 1950s and 1960s, Clough's approach to painting became more abstract. The figures gradually disappeared, and her compositions began to focus on the shapes and textures of buildings and objects.

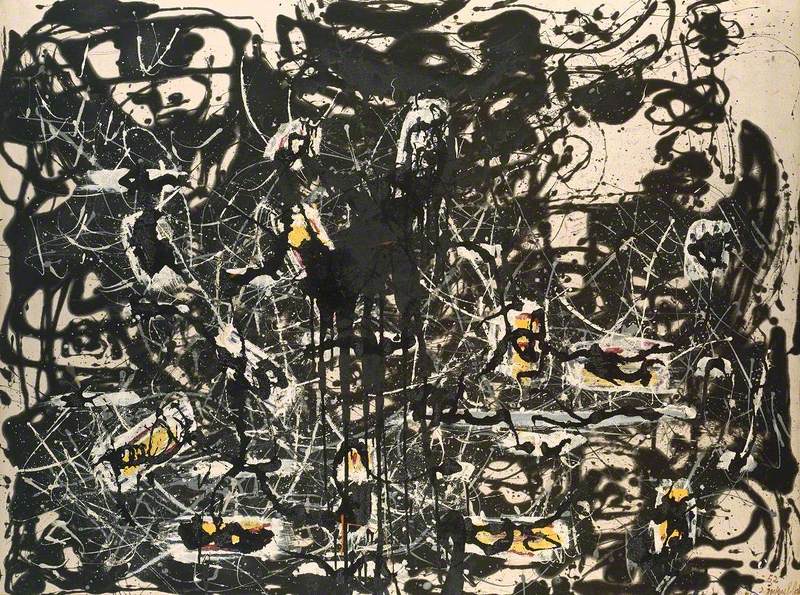

Developments in European and American abstract painting fascinated and exhilarated Clough. She was inspired by the textured paintings of Spanish artist Antoni Tàpies, and described the abstract landscapes of French painter Nicolas de Staël, which she saw in exhibitions in London, as 'succulent and exciting'.

In 1959, an exhibition of American Abstract Expressionist painting at Tate, made British painting with its emphasis on social realism, seem suddenly old fashioned. Artists such as John Bratby and Derrick Greaves, referred to as 'Kitchen Sink' painters because of their focus on domestic scenes, dominated British painting at that time.

After seeing the American exhibition at Tate, which included work by Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, Clough remarked: 'The Americans happened to England and if you were alive and sentient you shared in it.'

Despite moving towards abstraction, however, Clough never lost sight of the real world. Even in her late paintings and prints, which on first view look completely abstract, there are traces of everyday sources.

Sources and starting points

How did Clough develop her extraordinary visual language and transform the mundane and ordinary into richly worked abstract paintings?

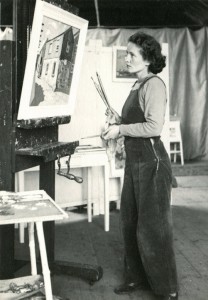

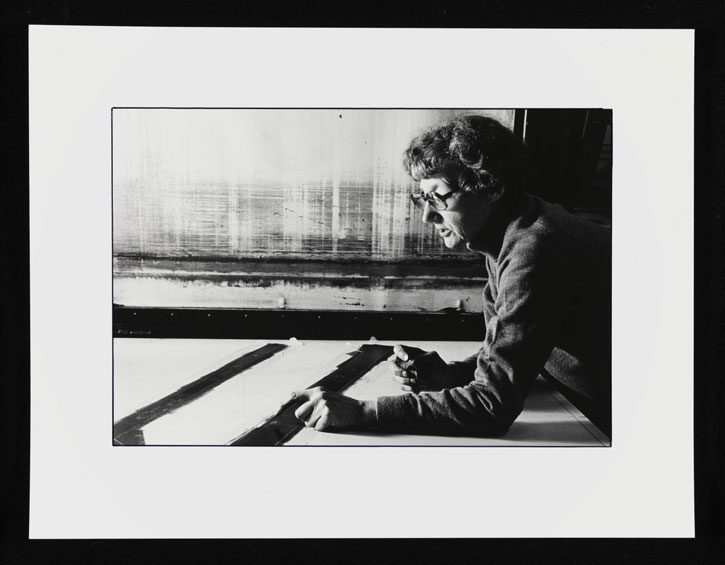

A collection of her notebooks, photographs and the 'tools' she used for painting in Tate's archive provide us with a revealing glimpse into her techniques and processes.

Black-and-white photograph of Prunella Clough in her studio

1982, photograph by Geoffrey Dann

She carried her camera everywhere and snapped things that she found interesting. She first started to do this in the 1950s. Small black-and-white photographs show industrial yards and buildings; rusted and patched corrugated fences; and other seemingly mundane details that caught her eye. (Some of these photographs have paint splatters and smudges, suggesting that they were very much to hand as she worked.)

Black-and-white photograph of corrugated iron hoardings

1950s, photograph by Prunella Clough (1919–1999)

Later colour photographs reflect her continued passion for capturing everyday details. Repeated themes emerge: stacks of brightly coloured buckets, plastic chairs, muddled coils of rope, wire and netting, lights and shadows, textures and surfaces.

Colour photograph of the shadow of a bicycle on the pavement

1990s, photograph by Prunella Clough (1919–1999)

But Clough didn't simply make paintings directly from these photographs. They act as a sort of reference library of shapes, textures and colours that she rummaged through for inspiration.

She was interested in the abstract qualities of everyday things and her photographs often show unexpected views of objects. She hones in on details or frames things in such a way that they are surprisingly cut off. By using crops and unexpected views, Clough interrupts our perception of ordinary objects and buildings, making us notice their shapes, patterns and textures.

Another important source of ideas for Clough was her notebooks. Photographs can record how places, people and things look, but she also wanted to record how she felt when she saw them.

Lists or clusters of words capture the atmosphere of a place or a scene. On her visit to Rotherhithe in January 1953, she noted:

'Yards. Old obj. covered scrap. barrels

oily wet

Red-grey / mid pink

Violet sign, dark nr. door rough [?] cerulean

barrel

wavy [?] dilapidated edges / or pale concrete

pre-cast walls

multiple verticals, cylinders up

Roads, curved, marks / light toned'

There is a strange poetry to these pithy journalistic descriptions. As former Tate Archivist Sue Breakell suggests:

'She [Clough] is almost creating word sketches… but she is not describing a whole scene, just the elements that she is noticing – so it's quite abstracted… She is trying to create an atmosphere to take away with her rather than a description… the memory of the experience of seeing something'.

Tools and technique

As well as source images and notes, Clough also developed a collection of tools and materials. She used sandpaper, wire wool, rollers and wire mesh to scrape, gouge, scratch and obliterate.

She also experimented with media, sometimes mixing materials such as sand and stone dust into her paint. Her archive includes stencils, which she dabbed and rolled paint through. Some of these are 'found' objects such as metal grills or draining racks, others she made by cutting shapes into bits of card.

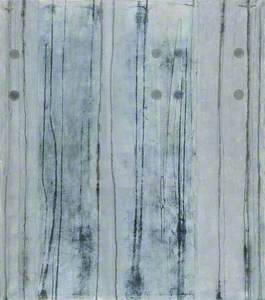

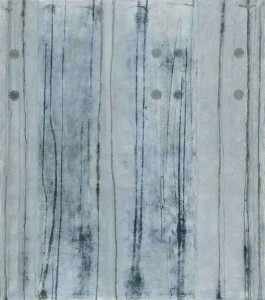

Landscapes of the mind

In 1949, Clough had told Picture Post magazine 'each painting is an exploration of an unknown country'. She saw her later abstract paintings, with their richly layered surfaces, as landscapes.

During the Second World War, Clough was conscripted by the War Office as a draughtsman and cartographer. It is tempting to see the influence of this early map-making experience in her use of simple lines and shapes to approximate landscapes.

Often these lines and shapes are painted over as she worked, leaving only traces of their presence. Perhaps, as art historian Frances Spalding has suggested, these paintings are not visible landscapes but instead are landscapes of the mind: 'like the passage of thoughts: layered and interwoven, arbitrary and interconnected.'

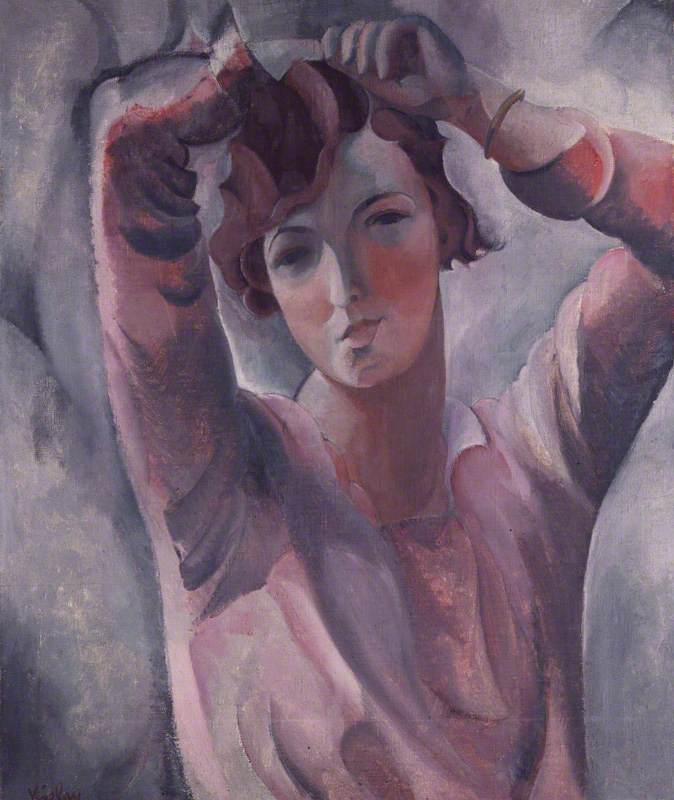

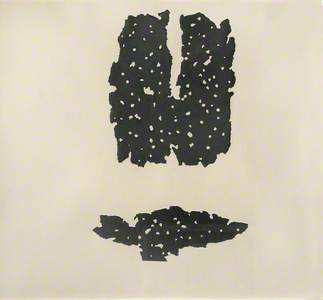

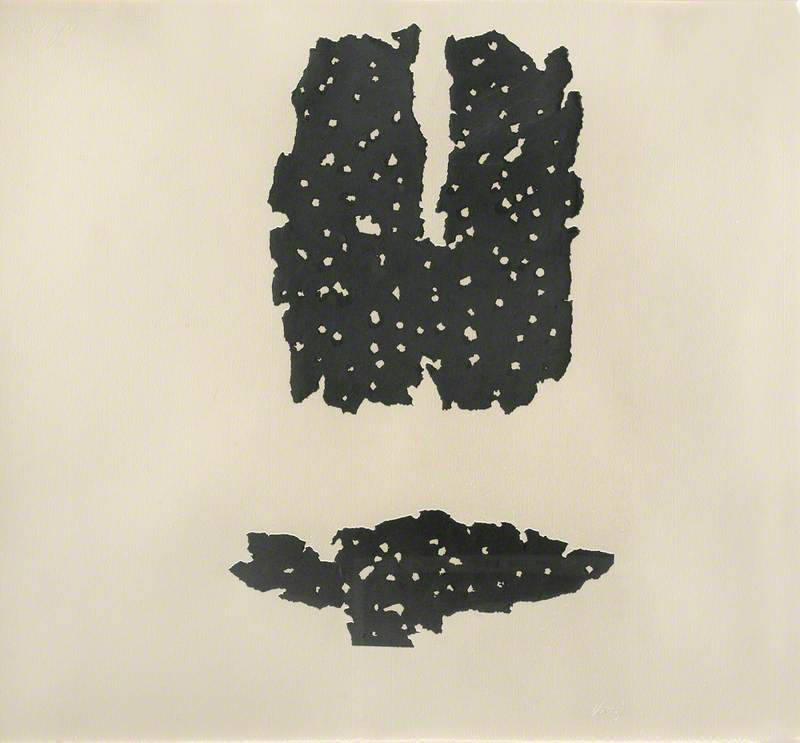

Study for 'Perforated Fragment'

1985

Prunella Clough (1919–1999)

What is Prunella Clough's legacy?

Clough was an important artist in the post-war years and her paintings were exhibited regularly in commercial galleries and public exhibitions during the 1950s, including in a highly acclaimed retrospective exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1960.

But since then she has never really had the recognition she deserved, and it is only relatively recently that there has been a renewed interest in her work. Perhaps her lack of wider recognition is due to the fact that she worked alone, (despite having lots of friends, she was a very private person), and developed a unique approach that was not part of a wider artistic movement.

It could be that her work is hard to define – it hovers between abstraction and figuration and is also surprisingly diverse.

Art historian Gerard Hastings has suggested that she was side-lined because she painted subjects traditionally associated with men: the workplace, industrial scenes, buildings and structures. Whatever the reasons for her relative obscurity, Prunella Clough changed the way we look at and think about the ordinary every day.

'If you see a Prunella Clough you know you are looking at a Prunella Clough, but when you then go out onto the street, you can still see them. It’s as if they come out of the gallery and into your life, into your looking.'

Maggie Hills, Project Officer at Art UK

Further reading

John Berger, 'Machine-Life Painting' in New Statesman, 18 April 1953, quoted in Frances Spalding, Prunella Clough: Regions Unmapped, 2012

Sue Breakell and Gerard Hastings, 'Look Again: The Visual Language of Prunella Clough', Tate

Frances Spalding, Prunella Clough: Regions Unmapped, Lund Humphries Ltd., 2012