Dealing with the subject of racial inequality in twenty-first-century Britain and the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade in Bristol pervades all aspects of our art curatorial and wider museum work. From exhibition and displays to research and cataloguing, and, importantly, community engagement, working with and listening to our audiences.

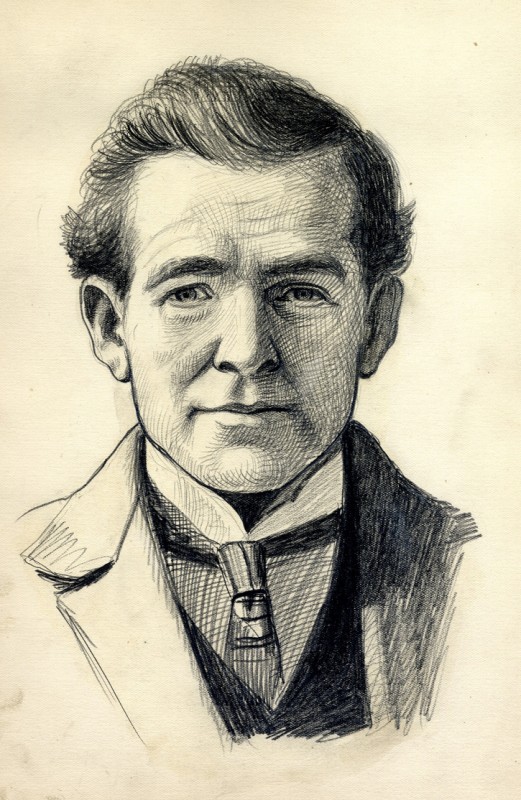

Edward Colston (1636–1721)

c.1726

John Michael Rysbrack (1694–1770)

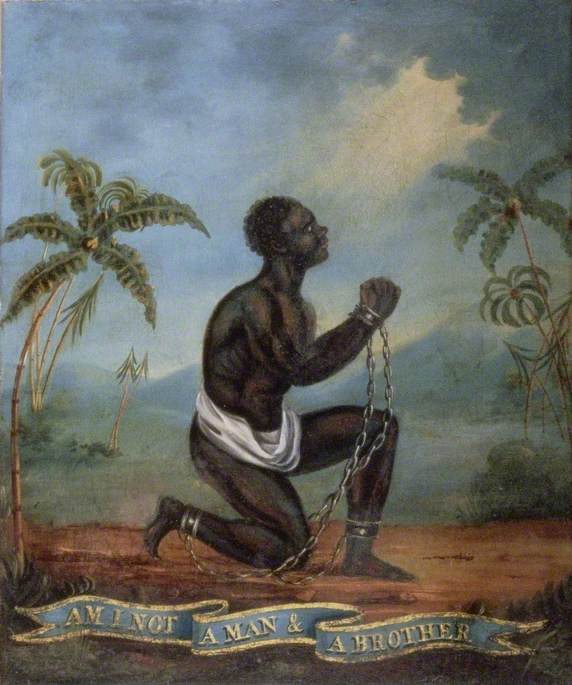

In 2017 we published the first print Guide to the Art Collection in 40 years. We knew we had to include Rysbrack's portrait of Edward Colston in order to represent Bristol's involvement with the transatlantic slave trade and also to account for the enduring and controversial presence of Colston in the city, in the names of streets, schools and buildings – and on the plinth in the centre. Here's an excerpt from the guide:

Many port cities in Britain, including Bristol, profited from the transatlantic slave trade. Edward Colston is probably the best known of the Bristol merchants who benefited, in equal parts due to his role in the Royal African Slave Company and his philanthropy to Bristol. His wide-ranging business interests included trading in wine and cloth from Europe... but it was as an official of the London-based Royal African Company (which from 1672 until 1698 held the British monopoly on the slave trade under Royal licence) that he was directly involved in the trade, organising the sale and transport of enslaved Africans to the Caribbean.

Many of our seemingly most familiar stories such as the Bristol School of Artists (active from c.1810 to the 1840s) and the famous topographical collection of George Weare Braikenridge (1775–1856) need to be looked at afresh, to achieve a more differentiated view of this crucial period in Bristol's history.

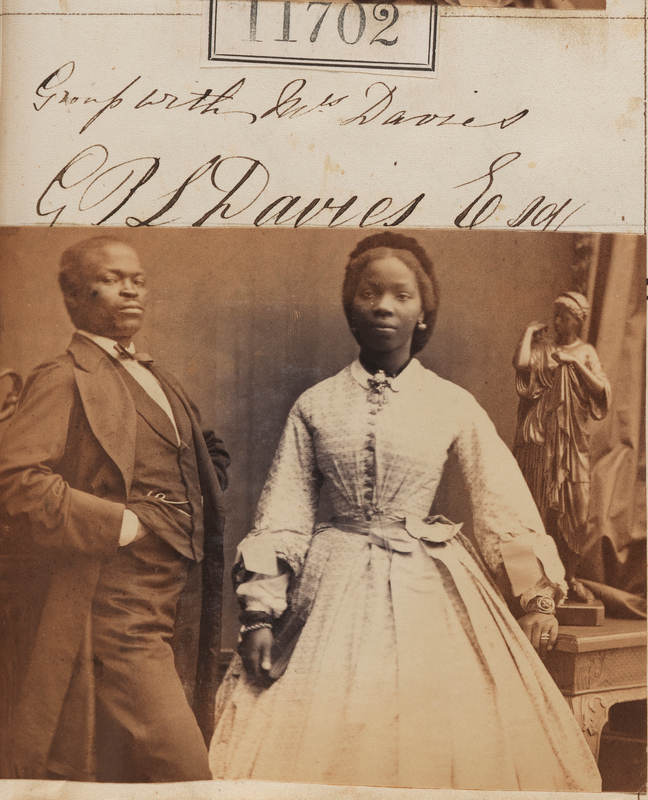

For example, while Bristol School artists such as Samuel Colman and Francis Danby show abolitionist sentiment in their paintings, the local patron Braikenridge was only able to commission his famous views of Bristol because of the money he had earned as a West Indies merchant and on the back of compensation payments. In 1837 his company Braikenridge & Honnywill received more than £2,911 8s 6d, for 157 enslaved persons in Jamaica whom they had been forced to release on emancipation.

New curatorial research on the historical background of the Bristol School is ongoing (and open-ended) and we are sharing new information, such as the financial context to Braikenridge's commissions in the publication that will accompany our exhibition of Bristol School works at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux in the summer of 2021.

Moreover we will rewrite all our interpretation and will revise our display at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery when the pictures return from France in order to tackle these uncomfortable truths. Here, community involvement will be key in reviewing and responding to new findings and in determining the focus and tone of the new displays.

We are conscious of the lack of ethnic and social diversity of our European art galleries. Collecting additional historic artworks to address racial imbalance is always 'reactive' and dependent on what the art market brings to light. So we were excited to acquire Henry Hoppner Meyer's 1827 abolitionist painting The Young Catechist in 2019.

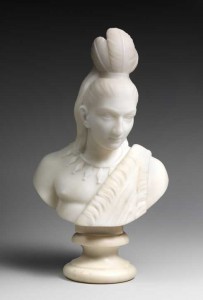

We are also looking at the existing collection in a new light. One of the museum's earliest acquisitions was H. P. Briggs' full-length portrait of the Indian reformer Rammohun Roy. We plan to redisplay it in our Grand Tour gallery, facing Thomas Lawrence's portrait of the Duke of Portland.

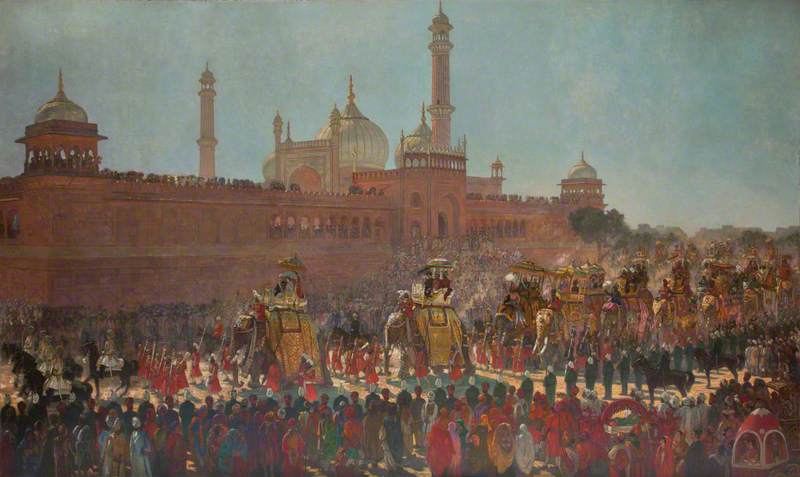

In 2012 the British Empire and Commonwealth Collection was transferred to the museum. This included the huge painting of the State Entry into Delhi by Roderick MacKenzie, painted to mark the coronation of Edward VII and the Delhi Durbar held to declare him Emperor of India on 1903.

The State Entry into Delhi

1907

Roderick Dempster MacKenzie (1865–1941)

We realised this painting, made at the height of the Raj and from the perspective of the colonisers, required new interpretation for the twenty-first century. In 2014 we held an international seminar, funded by the Paul Mellon Centre and invited specialists as well as community representatives, to take this forward. The painting was also selected by a group of young people to interpret as part of The Uncomfortable Truths podcasts about museum objects launched in autumn 2019.

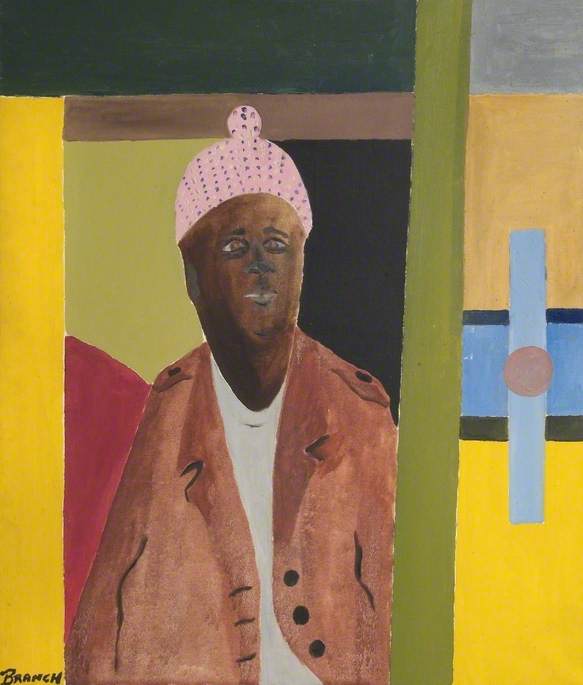

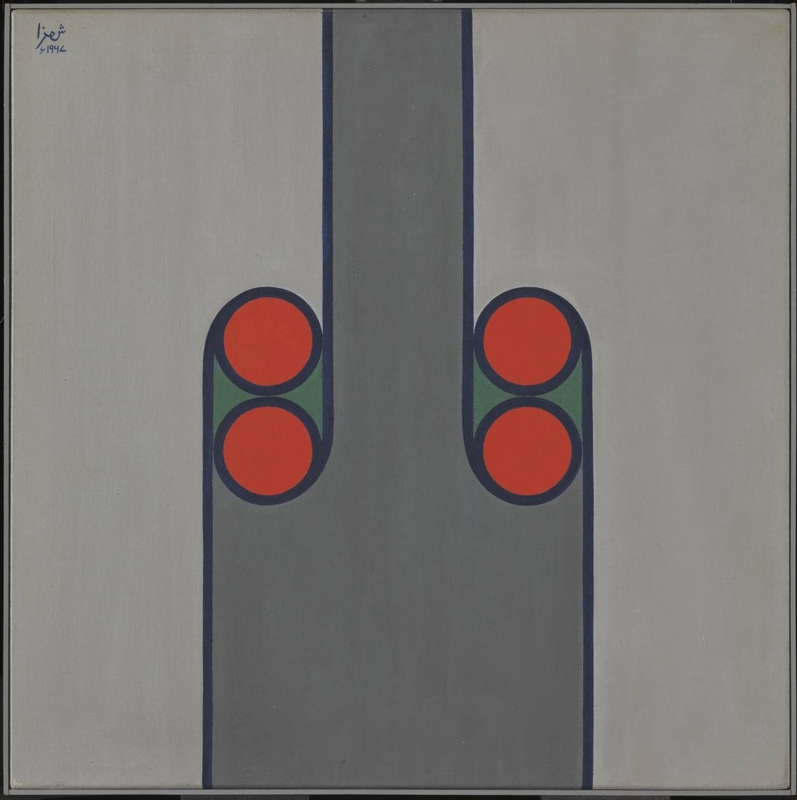

Our Art Funded programme of contemporary art collecting between 2007 and 2012 offered a major opportunity for us to examine the museum's historical collections through contemporary art from the locations represented: Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

Still from 'A Season Outside'

1997, video (30 minutes) by Amar Kanwar (b.1964). 'A Season Outside' is Kanwar's personal meditation on the nature of the Partition of India in 1947. Presented by the Art Fund, under Art Fund International, K6375

Forty-one new works were acquired, mostly offering a postcolonial perspective, such as A Season Outside, part of a trilogy of moving image works by Amar Kanwar that meditate on the Partition of India and its violent aftermath.

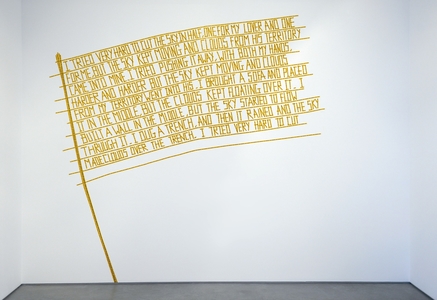

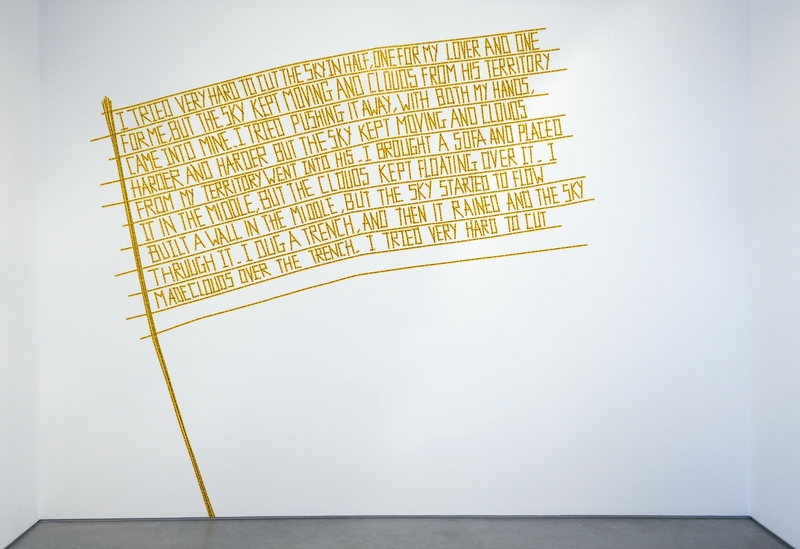

There is no border here

(edition 3 of 5) 2006

Shilpa Gupta (b.1976)

Shilpa Gupta's wall drawing made of hazard tape emblazoned with the legend 'No Borders' continues with this theme.

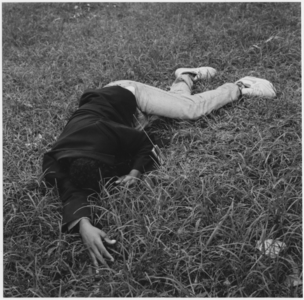

Dormeurs [The Sleepers] Tangier, Fig. 2

2006

Yto Barrada (b.1971) ![Dormeurs [The Sleepers] Tangier, Fig. 2](https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/w800h800/collection/BST/BMAGG/BST_BMAGG_K6306-001.jpg)

Sleepers, by Yto Barrada, photographed African migrants who had burnt their passports before travelling across the Sahara into mainland Europe and Lydda Airport by Emily Jacir, reimagines the Empire Line airway route into Palestine and the Middle East.

Still from 'Lydda Airport'

2009, video installation with urethane and epoxy model by Emily Jacir (b.1970). Presented by the Art Fund under Art Fund International, K6468.

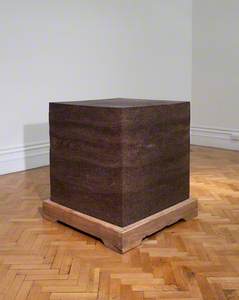

Perhaps the most renowned acquisition, A Ton of Tea by Ai Weiwei, considers the theme of global trade.

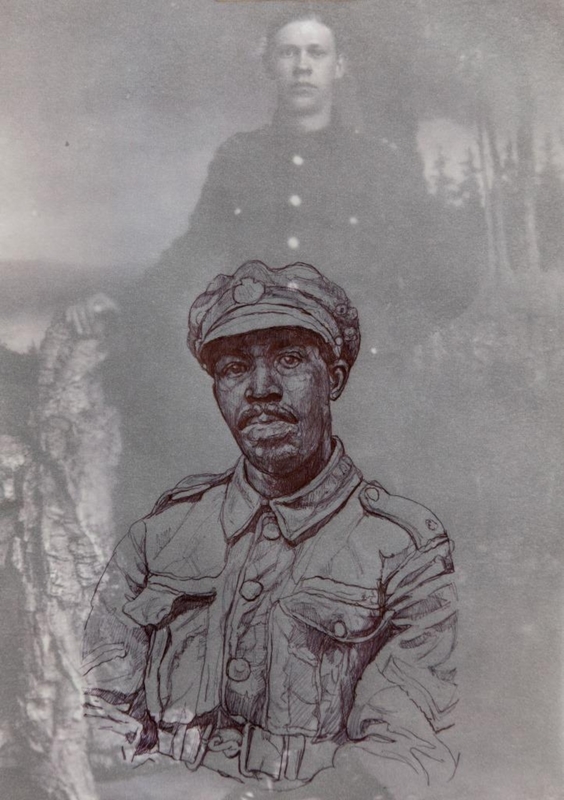

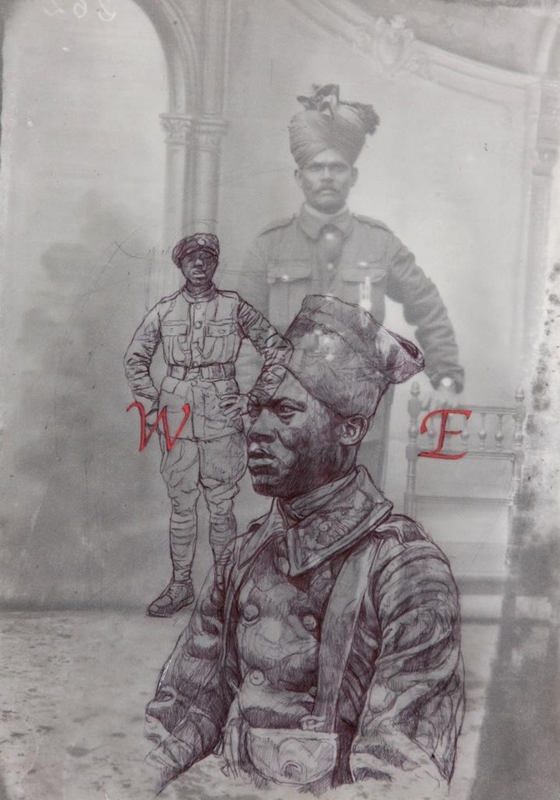

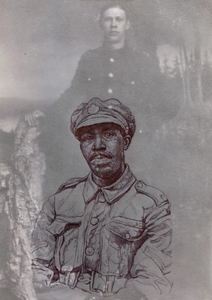

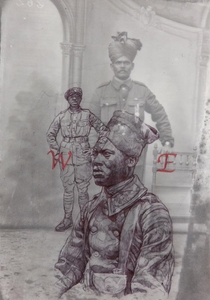

Art, contemporary and historic, can offer interpretations beyond the dominant narrative. Artists often work below the radar. Most recently we have acquired works by John Akomfrah and Barbara Walker that examine the involvement of soldiers from the Commonwealth in the First World War. Mimesis: African Soldier was commissioned by 14–18 NOW and has been jointly acquired with a gift from the Art Fund and 14–18 NOW with Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow.

Barbara Walker's drawings, I Was There IV and V were acquired through the Contemporary Art Society acquisition scheme for museums, with the support of our Friends organisation.

Both works use archive material to respond to the centenary of the First World War: Akomfrah in a powerful three-screen moving image work, Walker in intimately drawn images laid onto (but not obscuring) photographs of unnamed soldiers.

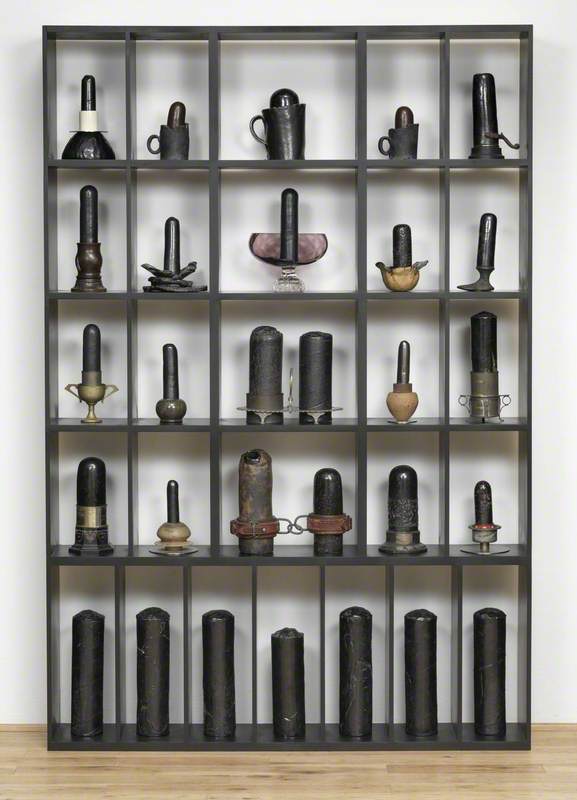

Another work commissioned by 14–18 NOW is Yinka Shonibare's End of Empire.

End of Empire

sculpture installation by Yinka Shonibare (b.1962)

Two dapper figures with globe heads wearing brightly printed suits astride a steam-punk seesaw, a symbol of Victorian industrialism. The fabrics are 'Dutch wax' textiles, an Indonesian batik printing technique pioneered by the Dutch in textile mills and imported by them and the British to West and Central Africa in the nineteenth century. The fabrics were claimed as their own by Ghanaians and Nigerians. The globes represent the two 'sides' in the First World War: the British-French allies versus the Austro-Hungarians and Germans. They are coloured with textile design indicating the African lands formerly colonised by the Europeans.

The seesaw swings slowly, constantly rebalancing, echoing the slow negotiation towards seeming freedom for the colonised, the titular end of empire. End of Empire makes a striking visual connection between the wars of the West, globalisation and empire. We have acquired it jointly with Wolverhampton Art Gallery with a gift from the Art Fund and 14–18 NOW.

With its global reach and its take on the closing of Empire, we plan to present it in our historic Grand Tour gallery where it will form an intervention among eighteenth-century portraits and the acquisitions made on the Grand Tour – and the mariner artist Nicholas Pocock's Battle of the Saints, which depicts the sea battle over Britain's colonial possessions in the Caribbean.

The Close of the Battle of the Saints

c.1782

Nicholas Pocock (1740–1821)

With the portrait of Rammohun Roy redisplayed in this gallery, we hope to use the collection to tell these wider stories.

Rajah Rammohun Roy (1772–1833)

c.1832

Henry Perronet Briggs (1791/1793–1844)

All this is just a start and our conversation with our audiences will take us much further – whether this is about renaming historic works or representing community responses in the gallery. We are excited to be part of this.

Julia Carver, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art and Dr Jenny Gaschke, Curator of Fine Art up to 1900, Bristol Museum & Art Gallery