Seamus Heaney was one of the best-known and most well-loved poets of the contemporary era. Born in County Antrim in 1939, in 1995 he received the Nobel Prize for Literature. It was during the 1960s that Heaney met artists Colin Middleton and T. P. Flanagan and these friendships provided him with opportunities to explore the visual arts in his poetry. Reading Heaney's work alongside paintings by these significant Northern Irish painters opens up new ways of looking at their work, and reveals the aesthetic sympathies they shared.

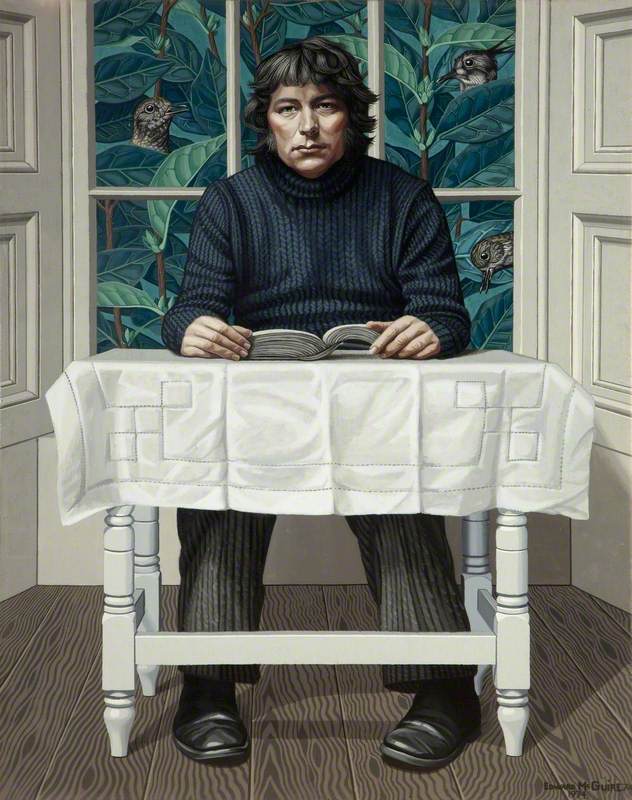

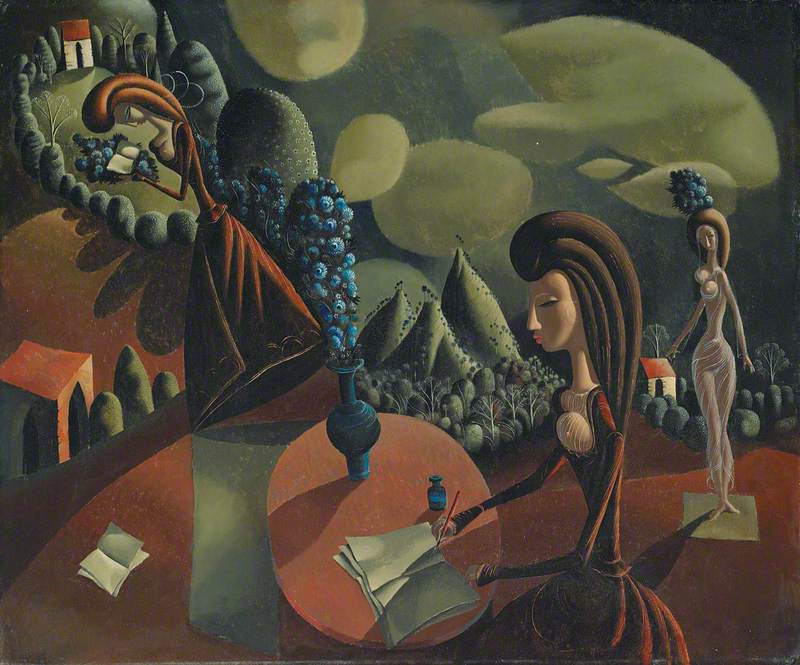

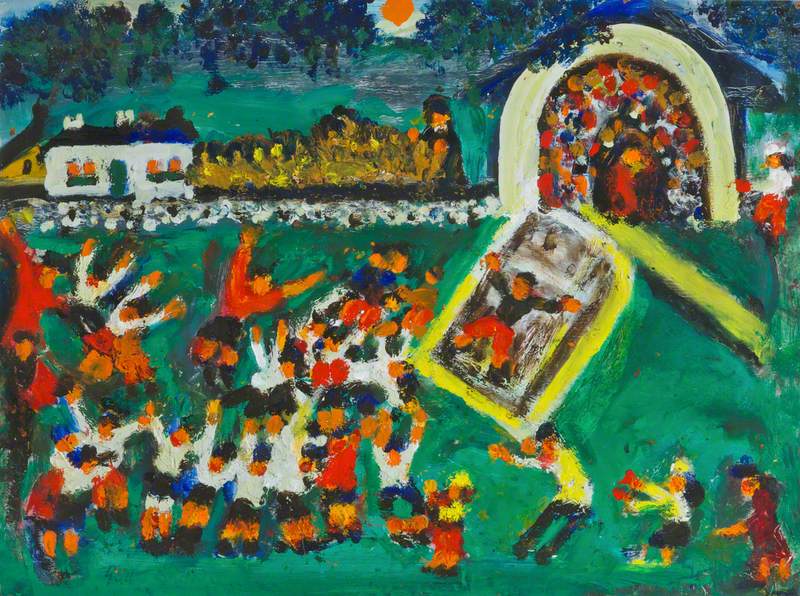

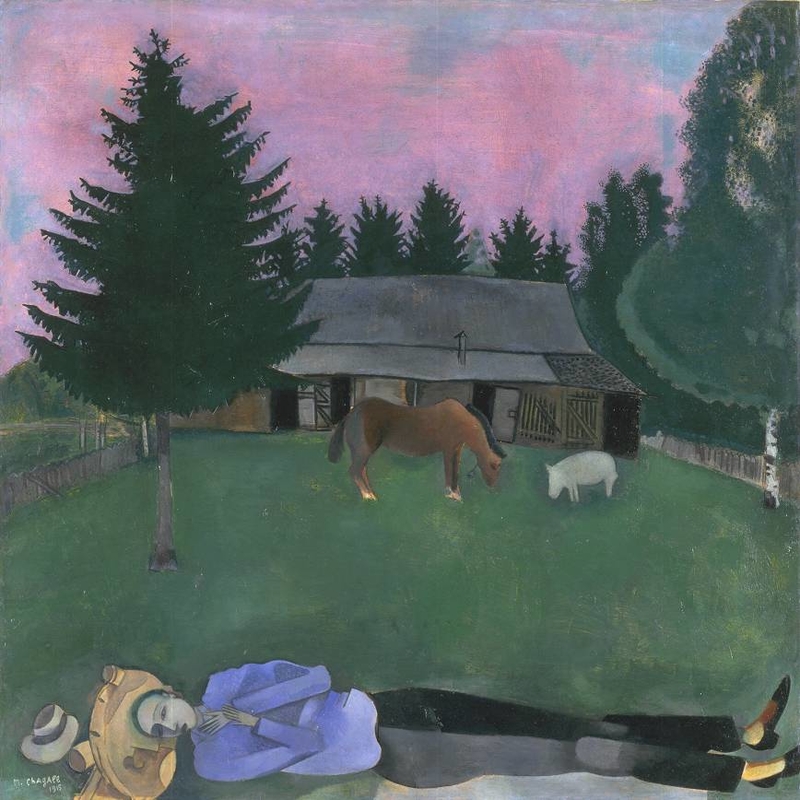

Colin Middleton, born in Belfast, worked in his father's linen damask design company while attending art college part-time. His accomplished draughtsmanship, owed to this professional background, is evident in his work. Middleton was a prolific painter, and while he experimented with a wide range of styles across his career, his work is often known for its surrealism.

Heaney dedicated two poems to Middleton, who had also been a poet in his own right. The first, In Small Townlands, was published in Heaney's debut collection Death of a Naturalist (1966). This poem was written after Heaney purchased a painting from Middleton. It describes Middleton in the active moment of painting, rather than describing the work as a finished piece. This sense of activity is conveyed by the poem's intense, even violent imagery – Middleton's 'hogshair wedge / Will split the granite from the clay'. In the poem, he will 'incinerate [the earth] till it's black / And brilliant as a funeral pyre'. However, this destruction is positive. In literally breaking down the landscape's forms, Middleton engages in an act of creation and transformation: 'A new world cools out of his head'.

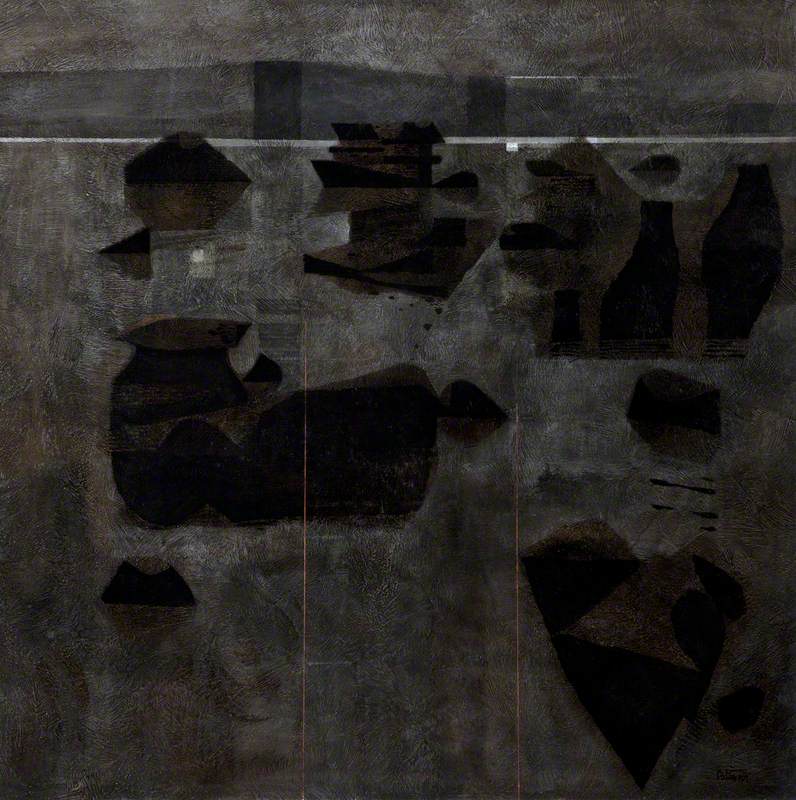

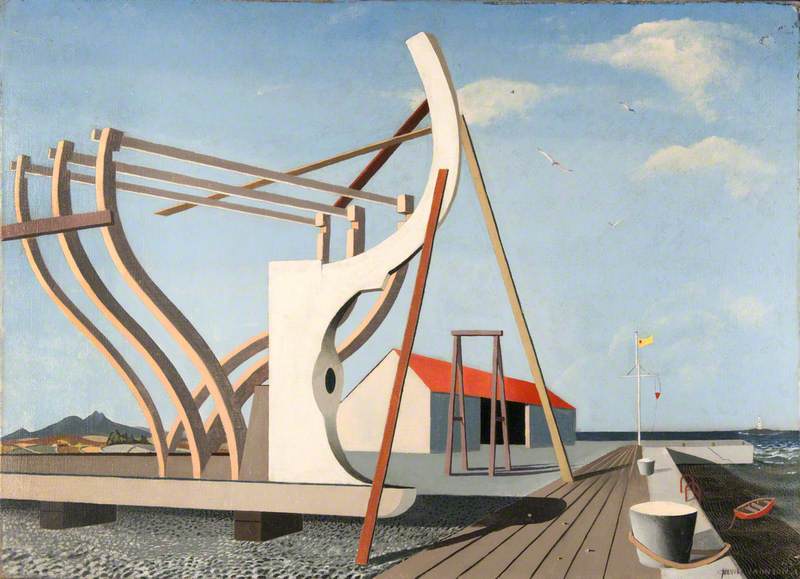

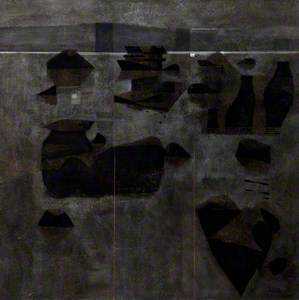

Heaney's approach is harmonious with Middleton's work during the 1960s. Sea Wall (1966) demonstrates Middleton's ability to deconstruct a landscape and reconstruct it with geometric shapes, a style grounded upon his early design experience.

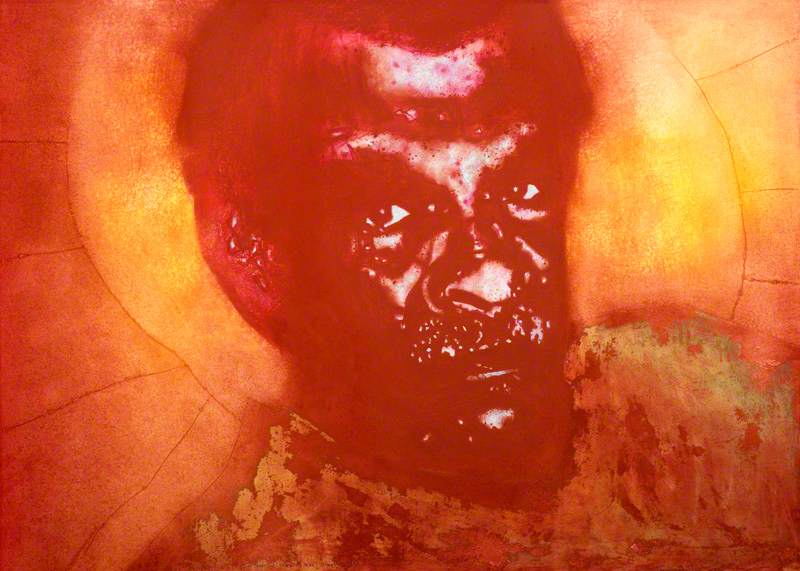

Middleton died of leukaemia in 1983. Heaney's poem Loughanure was written in his memory and published thirty years later. This poem appeared in Heaney's final collection Human Chain (2010), only three years before the poet's death.

Loughanure reflects both on the death of his friend and on artistic legacy more broadly. As an elegy, it asks unanswerable questions about the legacy left behind by an artist: 'So this is what an afterlife can come to? / A cloud-boil of grey weather on the wall'. These questions are especially relevant in a poem about an artist whose stylistic experiments were often misunderstood by critics during his lifetime.

It opens with Middleton 'gazing at' the painting that inspired In Small Townlands, facing the work of his younger self. In looking back to this painting following Middleton's death, Heaney forms a link between his first collection and what would be his last. This allows Loughanure to consider Middleton's development across his career alongside Heaney's own.

The imagery of Loughanure draws on Plato, Dante, the myth of Orpheus, Christian eschatology and Irish mythology but ends with 'Clarnico Murray's hard iced caramels / A penny an ounce over Sharkey's counter'. These contrasts between the grand and the everyday bring to mind Middleton's surrealist works, in which he employed both archetypes and personal symbols.

The poem tells the story of how Middleton would 'spread his legs, bend low, then look between them' so that something mysterious in his view could 'be unveiled'. This upside-down pose would allow the artist to see a landscape differently by rendering it unfamiliar. Loughanure reminds the reader of the impossibility of capturing a place, whether in a poem or a painting, in an objective, impersonal way. These landscapes are shaped by the unique perspective of the artist who paints them.

Similarly, Heaney does not let the reader forget that the landscapes he describes are channelled through his own perspective. Across the poem, Heaney describes failures of language and memory. Heaney laments his youthful inability to understand dinnsheanchas, meaning 'lore of place' in early Irish literature exploring the etymology of place names. In the poem, Loughanure is translated into 'Lake of the Yew Tree' and de-anglicised as Loch an Iubhair.

Heaney highlights the complexities of describing a place, as naming bears personal, historical and political weight. In an interview with Michael Longley, Middleton said that he (along with Flanagan) was 'addicted to places'. Middleton's idiosyncratic approach to perspective can be seen in paintings like Rocks at Sallow Point, in which distance is flattened, with vertical lines emphasising this effect.

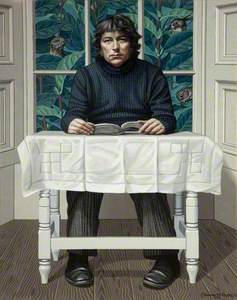

T. P. Flanagan was born in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh and studied at the Belfast College of Art. He met Heaney while they were both lecturing, Heaney at Trench House and Flanagan at its sister college St. Mary's.

Before meeting Heaney, Flanagan had (like Middleton) written poetry himself. This suggests a shared appreciation for language and a degree of creative sympathy between these painters and Heaney. Flanagan was, in Heaney's own words, 'romantic even bohemian' with a 'sensibility that inclines to the lyric and the opulent'.

Heaney recalled Flanagan working in a caravan with Basil Blackshaw, and even adopting the same bizarre pose he describes in Loughanure. He 'had once looked at the world – as instructed by Middleton – upside down, backside in the air, head between the legs'. These words portray a painter who, in Heaney's view, was unafraid to take on an unusual perspective.

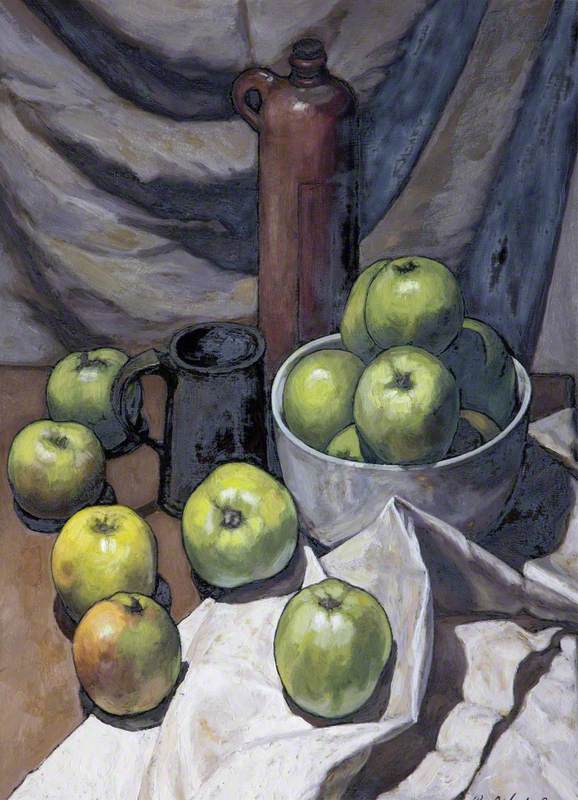

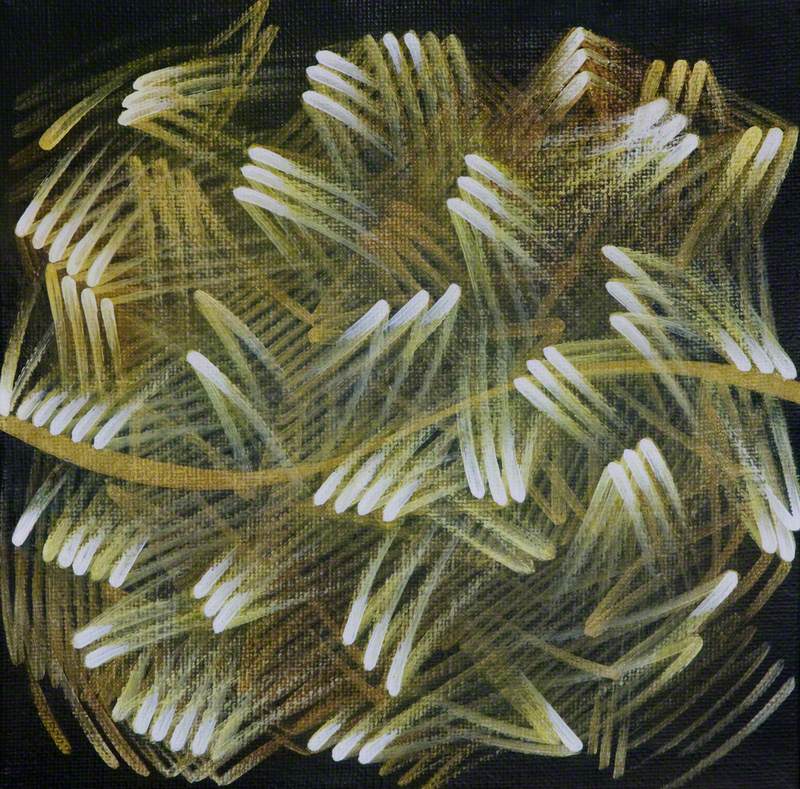

Heaney and Flanagan stayed together with their families in Gortahork and found inspiration in the same landscape, resulting in a creative exchange. Heaney wrote Bogland during this period, and dedicated it to Flanagan. The usual ekphrastic direction is reversed here, with Flanagan's painting Boglands (for Seamus Heaney) (1967) offered as a response to Heaney's poem.

Boglands (for Seamus Heaney) – held in a private collection – is an unusual example of a painter responding to a poet. In this work, Flanagan has picked up the poem's striking images: the concentration of the brush's movement into shapes like a 'cyclops's eye', the interplay of light and shadow evoking Heaney's image of 'salty and white' bog butter dug up from the 'kind, black butter' of the earth. Flanagan's work during this period, like Gortahork (2) painted the same year, displays a similar treatment of the Donegal landscape.

In dedicating Bogland to Flanagan, Heaney makes his poem's painterly aspirations clear. His description of the landscape as '[m]elting', full of 'waterlogged trunks / Of great firs, soft as pulp' mirrors the thick, unblended brushstrokes of Flanagan's style at this time. The act of painting remains noticeable, creating a sense that the piece has been finished recently and might not yet have even dried.

Heaney's telling of the excavation of a bog echoes the visual effect of Flanagan's landscape paintings with their visible brushstrokes and contrasts between piercing light and intense darkness. Flanagan's application of paint is like the layers of bog Heaney describes, his paintings capturing the 'bottomless' 'wet centre' of the Donegal landscape. In his own words, Heaney felt that Flanagan taught him 'to see blackness in brightness'. He continues, '...and every time I look at the sinuous dark line he made of that stream through sand, the excitement of his insight returns'.

For Heaney, Middleton and Flanagan, the representation of place is crucial. The Irish landscape inspired all three throughout their careers, and despite the differences in their mediums they were engaged in similar artistic conversations with their surroundings.

Eva Isherwood-Wallace, writer and researcher

This article was supported by the Esme Mitchell Trust