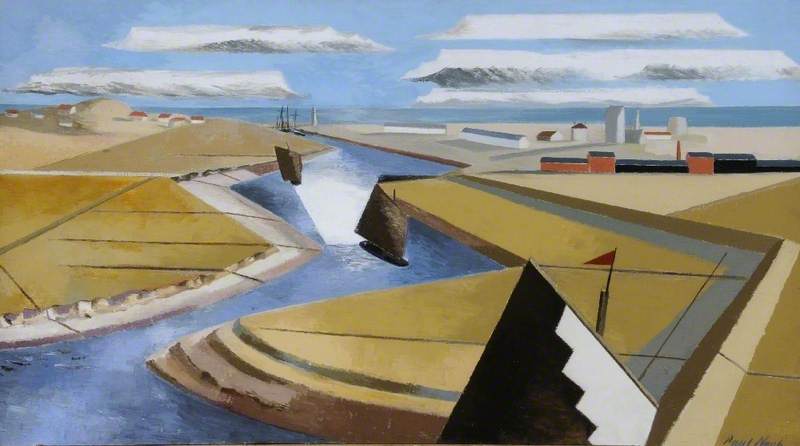

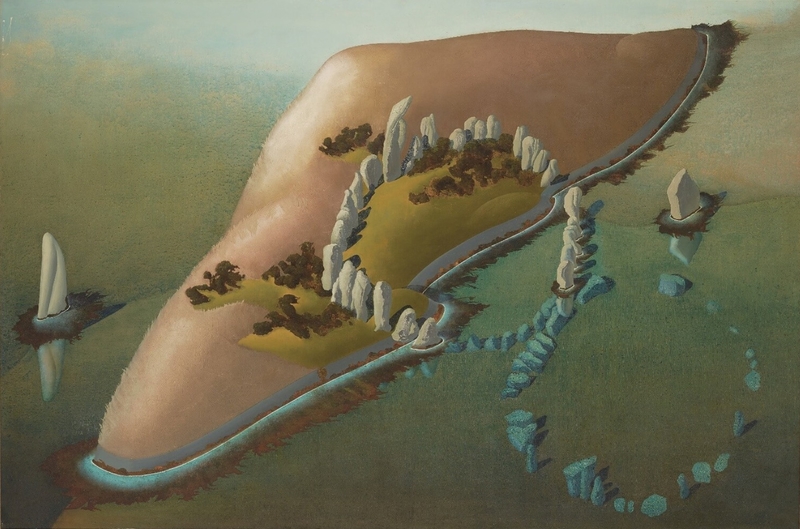

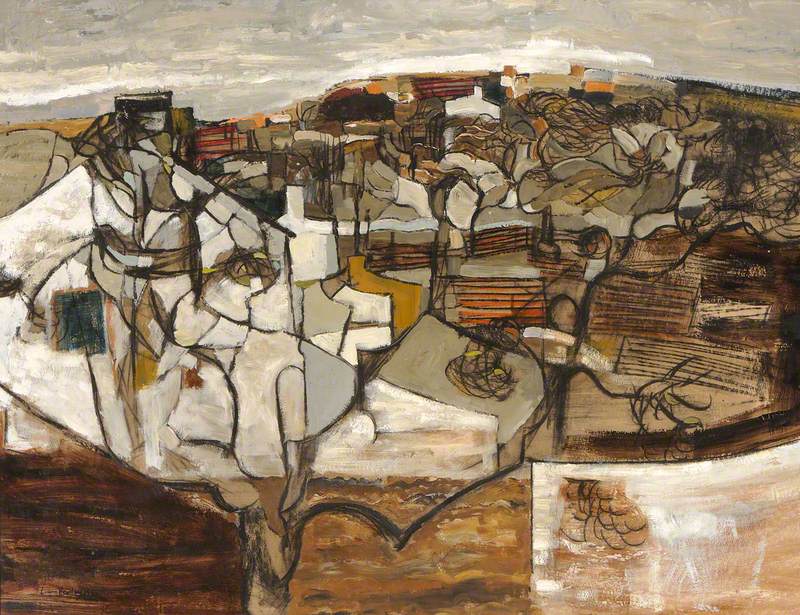

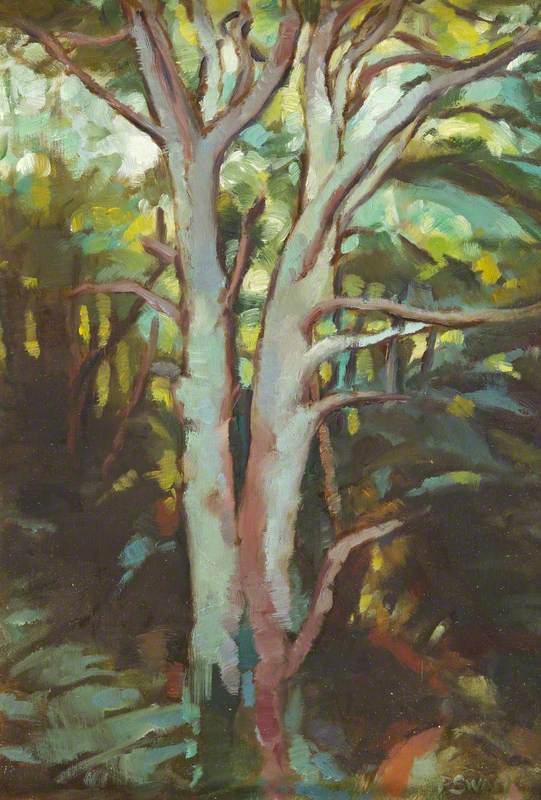

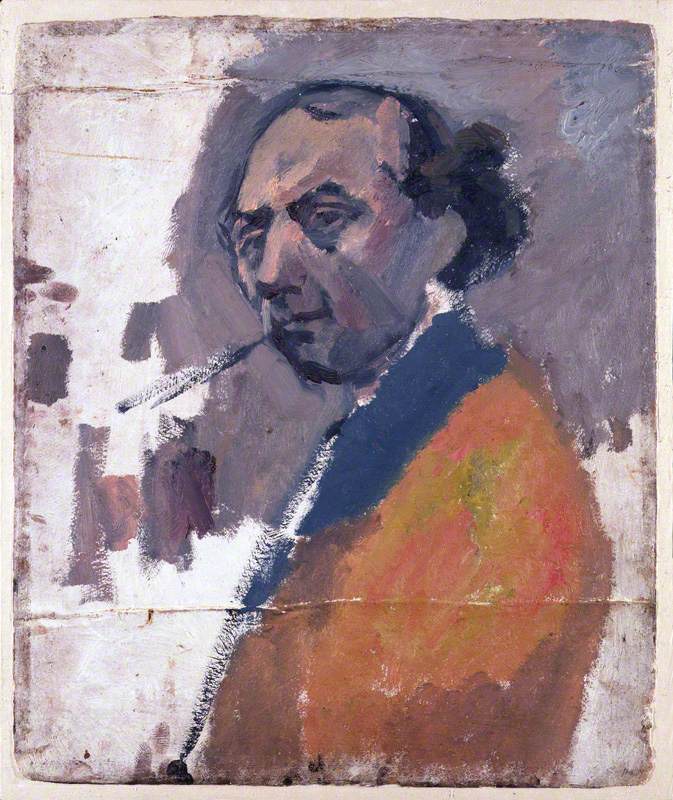

Paul Nash (1889–1946) is not especially famous, but he is relatively well known for delving into the world of abstract landscape painting and conjuring what might be called a metaphysical or spiritual aura in his paintings, often set in the south of England.

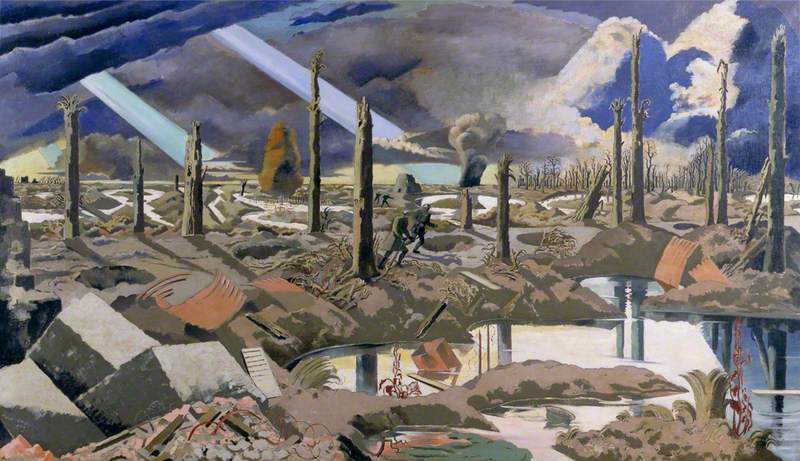

He is also known for his surrealist interpretations of the landscape together with his frank and emotive depictions of wartime destruction.

Nash managed to make us look at the landscape in three different ways – as a picture of the countryside, as abstract art involving colour, shape, mood and line, and finally a place that has what might be called 'resonance'.

What is essential about looking at and thinking about

What makes us zone in on a particular artwork or artist? Why might we be attracted to a specific painting?

Firstly we may recognise the artist's name, we might gravitate towards an artist that we have heard of. However, if we analyse why this particular artist has punctured our consciousness, we could deduce that they are either famous, for a variety of reasons or that their work appeals directly to us in some particular way that we have responded to consciously or unconsciously.

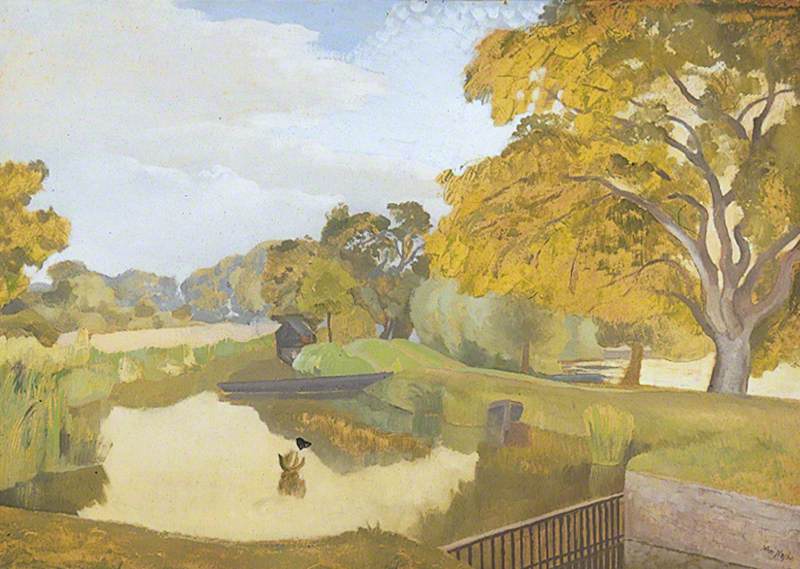

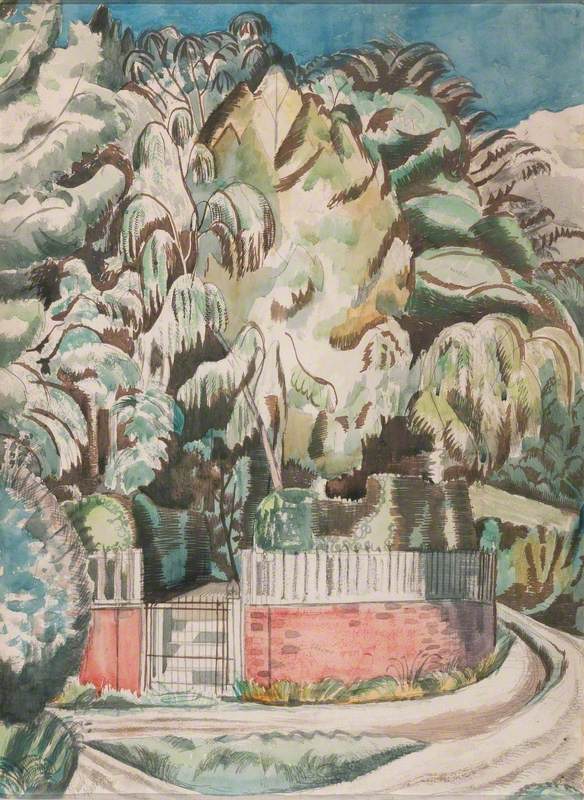

Nocturne, Landscape of the Vale is a modest view, dashed off quickly in watercolour and pencil which Nash uses to delineate the land, scrub, sky and moon. He does this primarily as an exercise in information

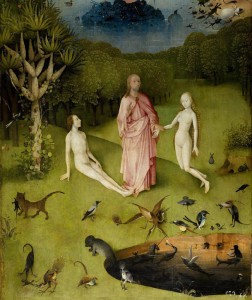

Nash's landscape work is locked into a very British painting tradition that was consolidated in the eighteenth century. At that time artists started to investigate the possibilities of landscape as a separate genre. Initially, this developed naturally out of landowners wanting a record of their wealth through the joint portrayal of people and property.

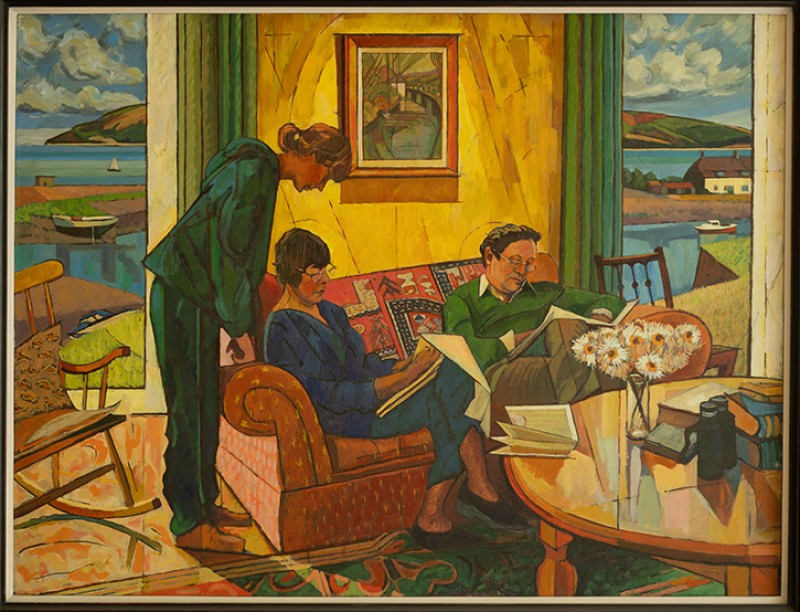

In Gainsborough's early, modest painting of Mr and Mrs Andrews we see a couple 'at home' in their domain. In later life, Gainsborough remarked: 'I'm sick of Portraits and wish very much to take my Viol da Gamba and walk off to some sweet Village, where I can paint Landskips and enjoy the fag End of life in quietness and ease.'

The Pass of Saint Gotthard, Switzerland

1803–1804

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Turner managed to turn his love of discovering the countryside into commissioned work, and throughout his

Travel provided the opportunity to hone his observation skills and focus on his private creative world. Quick drying and easy to transport, watercolour was a natural medium for him.

In contrast, Constable developed a method of using oils outdoors, his famous sky and cloud works have the veracity of the Impressionist moment and the impasto of the medium of oil. Like Nash, he identified strongly with specific places – both his Suffolk home and later Hampstead figure in his oeuvre.

Constable and Turner used both oil and watercolour, but someone like Francis Towne (1739/1740–1816), for example, focused almost his entire efforts on watercolour. Renowned as a tricky and unpredictable medium it requires the paint to be in an active fluid state in order to perform in both a controlled and a chaotic manner. Its character is both delicate and translucent. The secret is to possess the skill to conjure the balance between the fragile, transparent elements and know instinctively how much water to use to unlock the pigment from the gum Arabic, and then to let the process 'take off'.

The results are what we see in this simple little work by Nash – Nocturne, Landscape of the Vale. It is full of the zest of the moment, he has left his pencil workings like the remains of a febrile calligraphic text and incorporated these into the overall result. They underpin the structure but hover in the background of the patches of overlaid graduated colour, suggesting space, mood and atmosphere.

Norbert Lynton sums up Nash when he wrote the following in his essay 'Landscape as experience and vision', in the 1993 collection Towards a New Landscape:

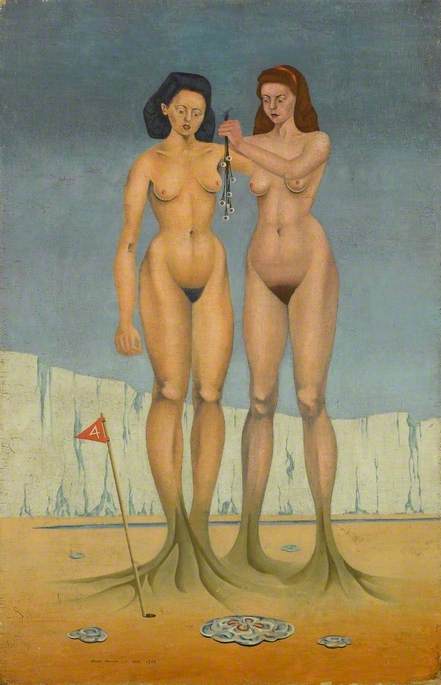

Nash's first works had people in them, bloodless creatures in the Pre-Raphaelite vein. Then landscape could stand for bodies,

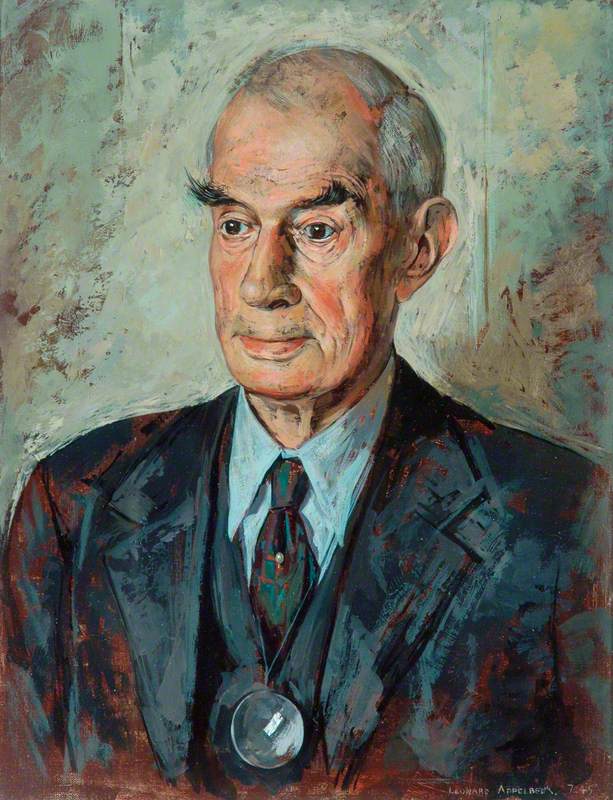

Liz Rideal, artist and writer