If people know of his name at all, Paul Fordyce Maitland is not usually thought of as an archetypal modern painter of London. Ask someone to think of the city and its history of Impressionism and the names that come to mind might be Monet or Whistler. Although both knew London, painted it and lived in the city, neither was a Londoner as Maitland was; he was an artist who had studied London through its rivers and parks which were less than a mile from his front door.

Paul Fordyce Maitland was born on 12th October 1863 in the parlour of the family home at 7 Edith Grove, between Fulham Road and King's Road, which was then in the Brompton area of London.

It appears Paul was born with scoliosis, a condition that causes side-to-side curvature of the spine. Although it impacts growth and quality of life, at the time of his birth it rarely led to total loss of mobility; throughout his life, he would walk and climb to strengthen his body.

His father Robert Forsyth Maitland was 55 when Paul was born. He had opened multiple businesses as a merchant over a period of 40 years. He was either very unlucky in business or, as Charles Dickens called his own father, 'a jovial opportunist with no money sense'; Robert was a serial bankrupt with spells of imprisonment and court appearances. Paul's mother, Margaret Birch, was 20 years younger than her husband and her family had climbed the twin ladders of respectability and wealth of London society. Her great-grandfather Samuel Birch had been Lord Mayor of London in 1814.

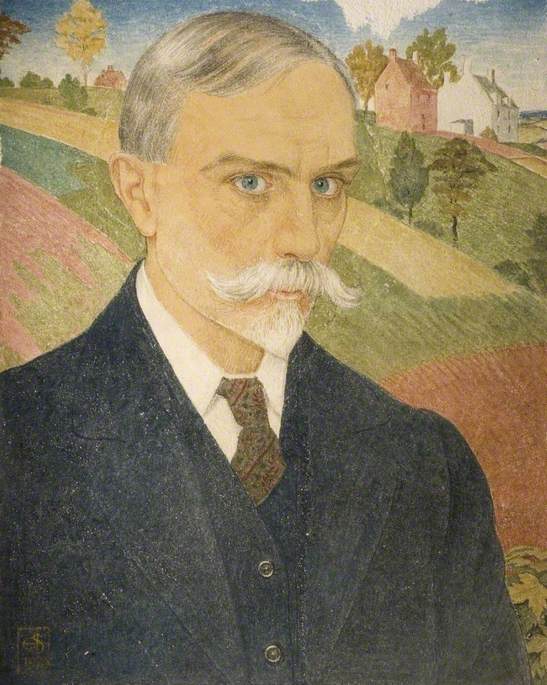

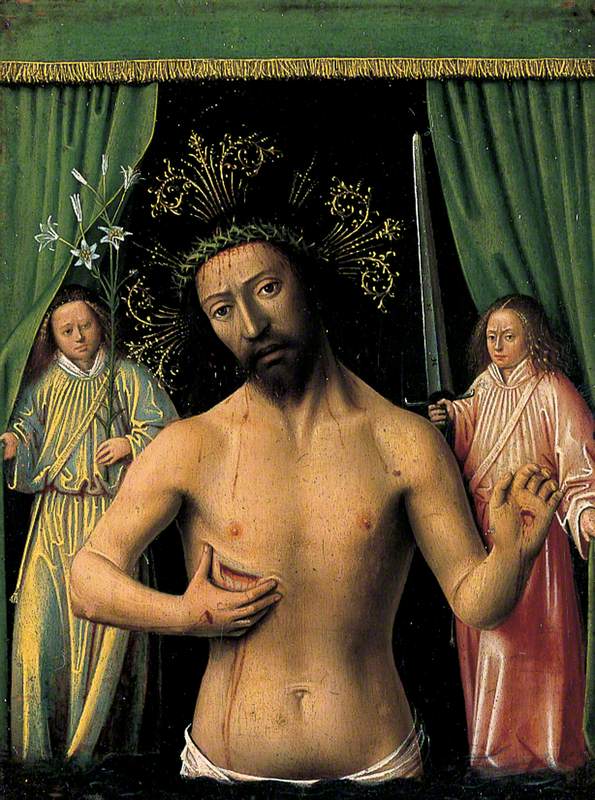

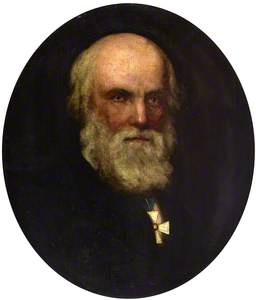

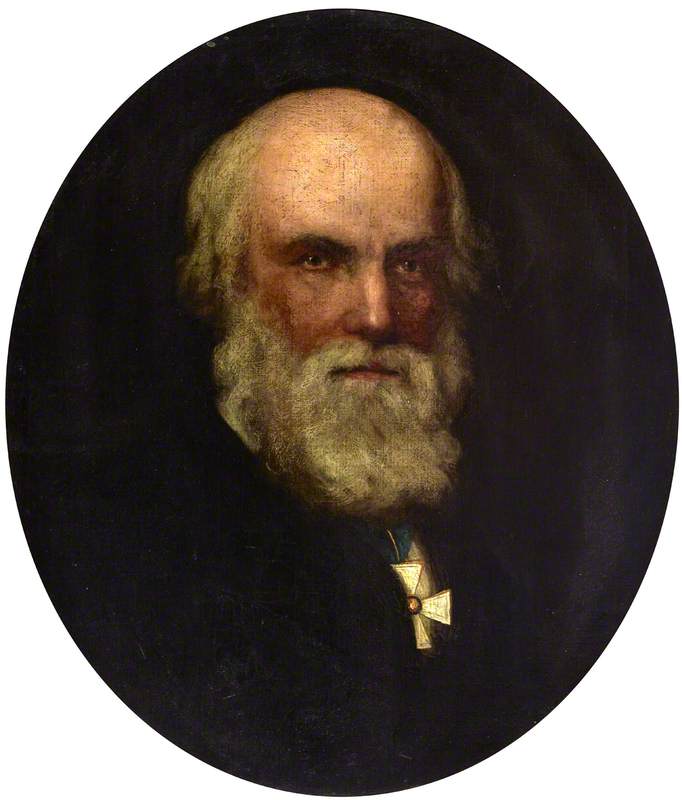

Dr Samuel Birch (1813–1885), Keeper of Oriental Antiquities (1861–1885)

after 1874

unknown artist

Samuel Birch's son, also called Samuel, became one of Britain's first Egyptologists. A noted Chinese scholar, he was Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities and later Keeper of Oriental Antiquities at the British Museum. In his lifetime he received considerable foreign recognition including the Prussian Order of the Crown. His portrait, in the collection of the British Museum, is well-executed and shows a competent hand – it is a possible candidate for further examination to see whether this is an early picture by his grandson.

In 1879, at the age of 16, Paul enrolled at the National Art Training School in London (the future Royal College of Art) which, due to its location, was informally known as the South Kensington Schools. It was on his first day of term that he met the man who would have the most profound effect on his life: the French émigré artist Théodore Roussel, who had arrived in England in around 1877. The two instantly developed a fond mentor-follower relationship that lasted until Paul's death in 1909.

In 1880, Roussel married his first wife Frances Bull and moved into 41 Edith Grove, just a few doors down from the Maitland household. It was a year that saw Paul pull out from his studies due to illness, though he resumed studying a few months later.

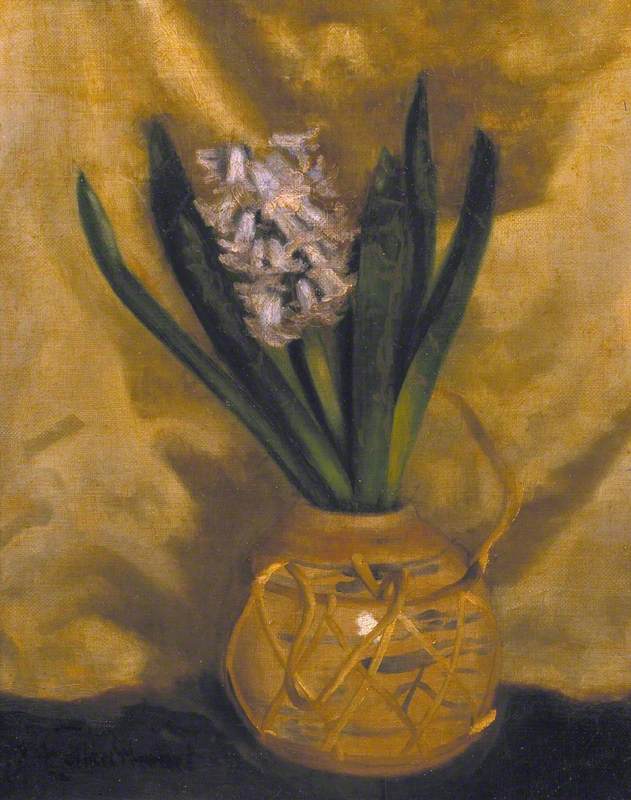

A painting from around this time first exhibited as Hyacinths in a Ginger Bowl is a rare example of Maitland painting a still life. The picture is a shade overworked, a little too self-conscious perhaps, but it is what it is, an academic exercise at a time the South Kensington Schools were training students to be future art teachers, designers and craftspeople, rather than artists.

After leaving the National School in 1883, the clubs, and social gathering places Roussel knew would have provided Maitland with the stimulation and contacts that were necessary to develop and promote his work.

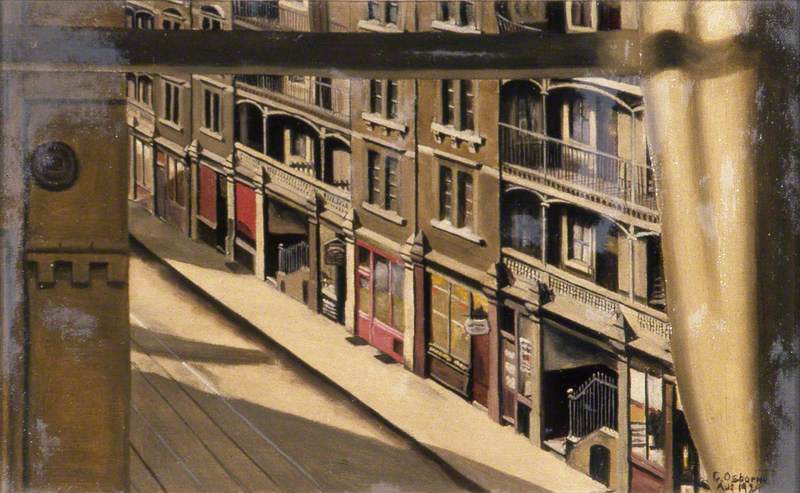

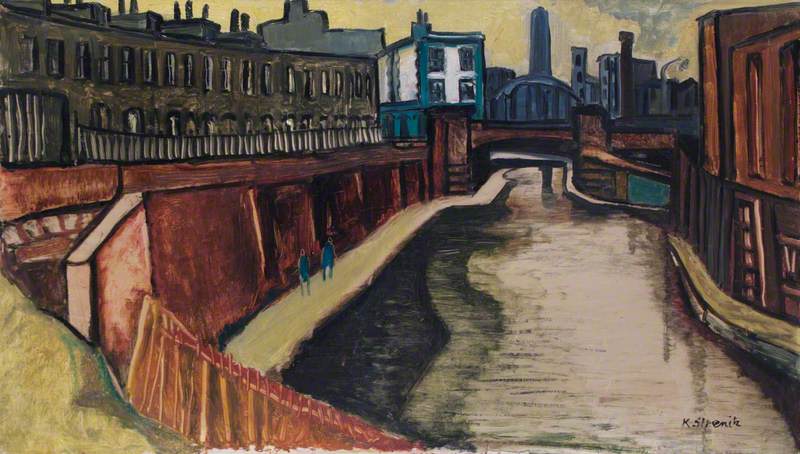

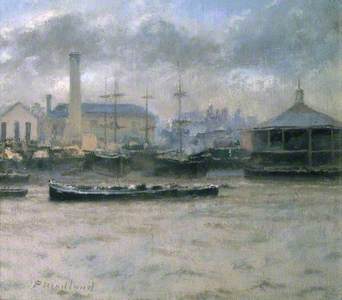

After his move to Chelsea, Roussel had begun to depict views along the Thames and the Battersea side of the river and he realised Maitland was a kindred spirit, an artist very much in his own mould who followed the poet Baudelaire's principles of depicting the landscape of great cities which has 'grown old and aged in the glories and tribulations of life.'

In other works of this period, Maitland concentrated on individual factories, wharves and warehouses or a stationary barge – most are shrouded in early-morning mist, the haze of summer morning or the Dickensian gothic fog for which London was famous in the nineteenth century. He chose to paint the old city of London in a modern way, and for this, there appears to have been a ready market for his work.

Although Maitland preferred to depict London's modern urban life, he travelled to paint in Kent, Buckinghamshire, Devon and Shropshire. He was painting out of doors in all weathers which, by now, had become a commonplace way to define impressionist landscape painting.

In the mid-1880s, Maitland's palette and style began to change, emphasising mood and tonal harmony, his compositions were more reflective and his handling of paint more confident.

This shift can be explained by Roussel's close association with James Abbott McNeill Whistler. The pair had met in 1885 after Whistler had admired Roussel's work at a London gallery. The Frenchman would go on to be one of the main repositories of Whistler's news, prejudices and opinions.

It was through this important link that Maitland became acquainted with Whistler and his circle, which included Walter Sickert, Philip Wilson Steer and other leading artists of the day. When Whistler became president of the Society of British Artists in June 1886 he used his position to promote his progressive friends and followers, Maitland among them. He also attempted to modernise the Society, reducing the number of pictures exhibited. The older hands rapidly became dissatisfied with him and, in the next annual election in 1888, voted Whistler out of office. Whistler resigned, as did Paul Maitland, along with Roussel and several others.

Within a short time, Maitland had joined the New English Art Club (NEAC) which had been founded by artists including Philip Wilson Steer, John Singer Sargent, Frederick Brown and Stanhope Forbes. The New English functioned on democratic principles, allowing members to control exhibition policy, quite different from the top-down decision making of both the Society of British Artists under Whistler's presidency and the jury system of the Royal Academy.

Maitland had joined the club a year after Walter Sickert, whose own arrival had crystallised a split within the NEAC between the more conservative artists and those who looked to the example of French Impressionism.

The latter appeared as a breakaway group, the 'London Impressionists', in an exhibition at the Goupil Gallery, New Bond Street, London in December 1889. The group's manifesto, published in the Pall Mall Gazette that November, tried to distance the group from the French Impressionists saying:

'it might be useful to clear away some of the misconceptions about Impressionism which exist in the public mind, if it is contended that the London Impressionists have been largely influenced by the work of their Parisian predecessors, it must also be remembered that many of the leading French Impressionists have admittedly been influenced by the work of the great English masters, notably Turner, and have in many cases, such as Pissarro have resided and worked in England.'

The ten painters taking part in the show were: Sickert, Francis Bate, Fred Brown, Francis James, Bernhard Sickert, George Thompson, Philip Wilson Steer, Sidney Starr, Theodore Roussel and Paul Maitland. Now aged 26, he was in a group of ten painters who would exhibit in the larger of the gallery's two rooms where Claude Monet had shown work the previous April.

The show attracted considerable press coverage of which many reviews were positive. The Graphic picked out two of Maitland's six pictures for special merit, with one newspaper ranking them above those by Sickert.

No records survive as to the financial aspects of the Goupil Gallery show, but there was no second show and soon afterwards the group disbanded.

Maitland has often been characterised as reclusive, but this is far from the case. He joined Roussel at his club of choice, the Savage, and was at the centre of Whistler's circle. Maitland was one of only 60 chosen guests invited to join a dinner in May 1889 to mark Whistler's 'influence upon Art at Home and Abroad, and to congratulate him on the honour recently conferred upon him by the Royal Academy of Munich, Bavaria.' Sickert was not invited.

At other times he went along to dinners at the Chelsea Arts Club where both Whistler and Roussel were founding members. The Club was conceived in 1890 as an association of 'professional Architects, Engravers, Painters, and Sculptors' and opened on the King's Road, Chelsea in 1891.

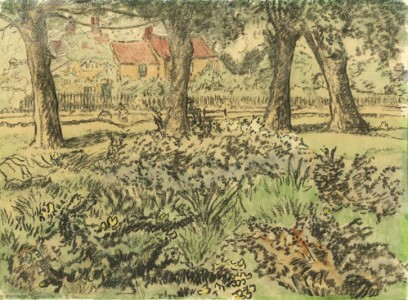

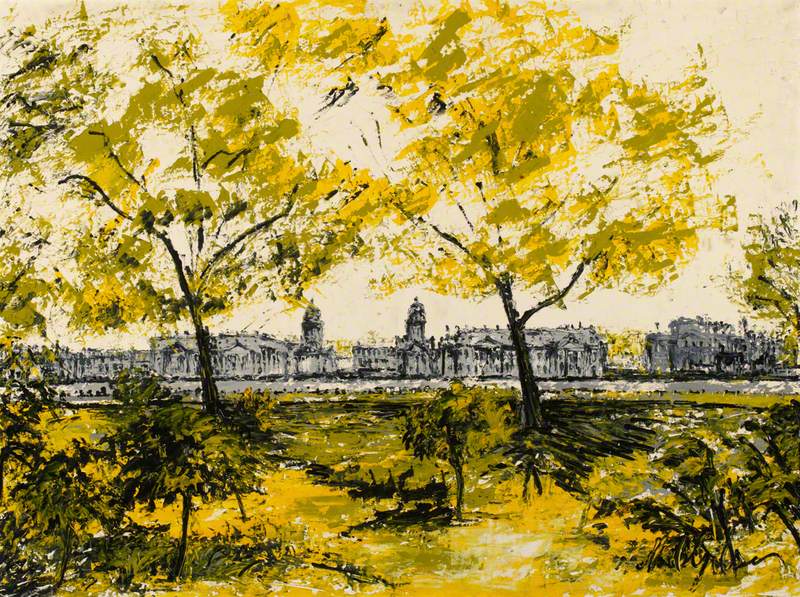

From the 1890s, Maitland was painting the London parks much as the French Impressionists had and still were (Camille Pissarro painted a well-received picture of Hyde Park in 1893) but here Maitland's pictures were radically different.

He was a casual observer, a flâneur, making small intimate pictures and, unlike the French Impressionists, he was pulling landscapes into a sharper focus, describing an ordinary world, places and people he knew. His pictures bound him to London, its place, its character and its culture.

His later work focuses on Kensington Gardens, a place where the local London wealthy and its visitors liked to perambulate and take in the fresh air. It was here he met an important patron, Elizabeth Forster, who lived at 2 Kensington Palace Gardens.

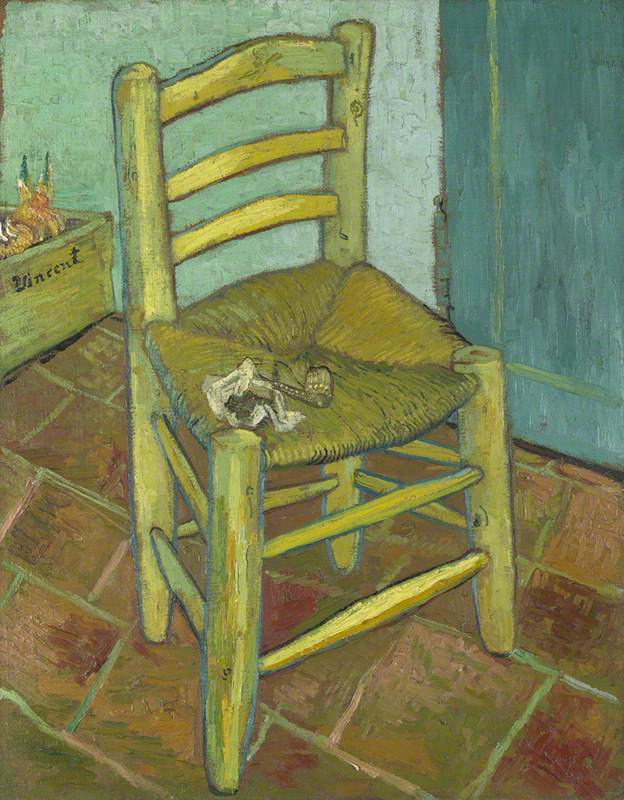

One of these park works, Kensington Gardens is so exquisitely painted and what at first appears to be a muted painting is in fact an awe-inspiring chromatic poem. It was made at a time of huge promise, when his work was shown at significant galleries both in London and abroad.

In 1893, one of the petty feuds of the art world occurred after Whistler had seen Sickert walking out of a New Bond Street gallery in the company of two of his enemies. Whistler resigned in rage from the NEAC, taking with him Roussel and Maitland.

A feud certainly but Sickert bore no reason to dislike Maitland and still regarded him as a friend.

That same year, Maitland was appointed an art examiner at the National Art Training School and on the death of his mother moved a short distance to 115 Cheniston Garden Studios in Kensington, where his neighbours included the artist Harrington Mann and the sculptor Emily Addis Fawcett. He also took a studio around the corner in Wright's Lane. In Sickert's foreword to Maitland's Leicester Galleries show in May 1928, he described walking with Maitland down Kensington High Street to his studio which he described as: 'piled around like an arena from the tiny pit of clear floor in the centre to the ceiling with his paintings.'

Maitland's career was going from strength to strength and there was a deep and appreciative audience for his work.

In May 1909 he travelled to Surrey with his friend and patron Arthur Collins who was a favourite Equerry of Queen Victoria, mentor for Princess Louise, Queen Victoria's daughter and Gentleman Usher to Edward VII.

They stayed at the home of their mutual friend Elizabeth Josephine Forster, who, as well as having a house in Kensington Palace Gardens, owned Shottermill Hall just outside Farnham in Surrey. It was here on 13th May, after a full day's painting on the Surrey Hills, Maitland died from a heart attack. He was 45.

For whatever reason, his body was not returned to London and he was buried on 17th May at St Stephen's Church in Shottermill.

In an obituary in The Times, a correspondent wrote: 'the death of Paul Maitland removes one of the most poetical and sympathetic painters of London scenery, particularly of Kensington Gardens, the Chelsea and Battersea reaches, and the old redbrick houses which still remain in the region of Cheyne Walk. In private life, Mr Maitland was a brilliant and scholarly talker on art and letters.' The Westminster Gazette published the news on its front page saying, 'few have painted London with such distinction, reticence and insight'.

The following year the Baillie Gallery held a memorial exhibition of Paul Maitland's work where 71 of his pictures were exhibited.

When an artist makes a subject his own, as Maitland did, it is impossible to ignore that artist's way of seeing and the true nature of the world he inhabited. It is the final twist that Paul Maitland has slipped through the cracks of history and has managed to elude wide recognition as one of the great, significant, British Impressionists.

Richard Morris, art historian

With thanks to Anna Gruetzner Robins, Margaret MacDonald and Frances Spalding

Richard Morris is cataloguing all of Maitland's work at paulfordycemaitland.co.uk

Further reading

Kenneth McConkey, The New English: A History of the New English Art Club, Royal Academy of Arts, 2006

Sylvie Patry, Anne Robbins, Christopher Riopelle, Joseph J. Rishel and Jennifer A. Thompson, Inventing Impressionism: Paul Durand-Ruel and the Modern Art Market, Yale University Press, 2015