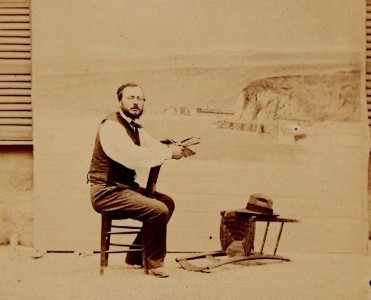

Art UK's collection of oil paintings by Sidney Herbert Sime only scratches the surface of what is a rich oeuvre of over 800 caricatures, landscapes, portraits, drawings and illustrations held at Worplesdon Hall's Sidney H. Sime Art Gallery.

Sidney Herbert Sime's art on display in the gallery

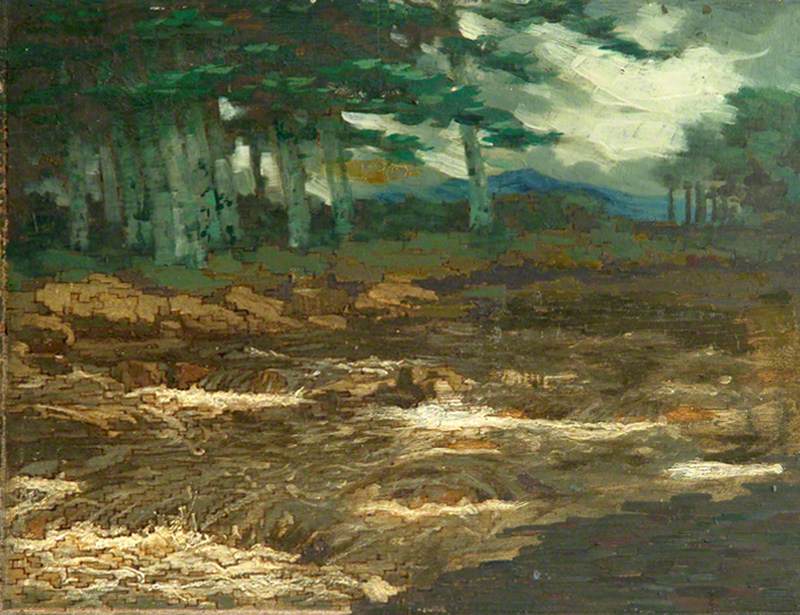

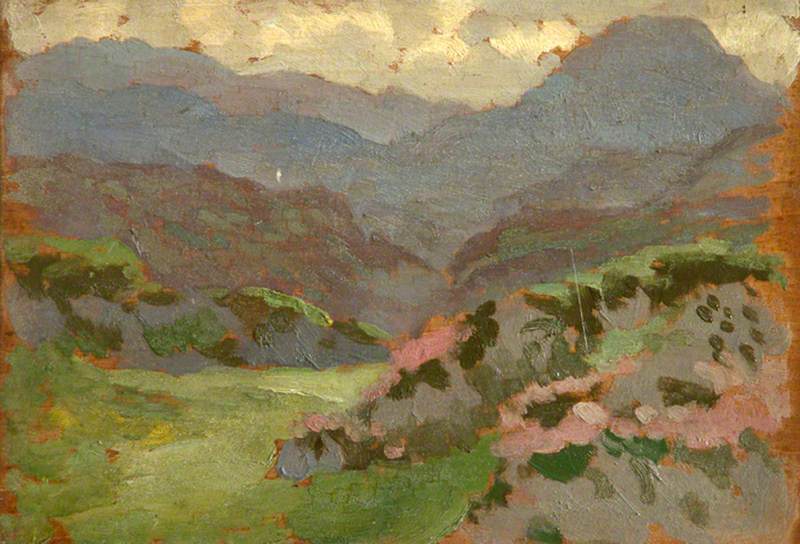

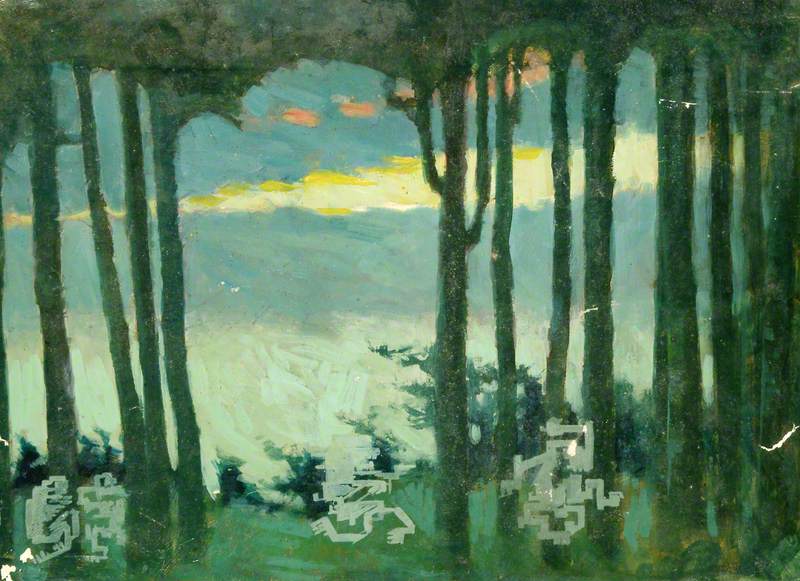

As I had worked as Senior Editor on the Public Catalogue Foundation's oil paintings cataloguing project, I had first approached the artist from the perspective of that medium. Sime's oil works are mainly landscapes in warm muted tones, devoid of people, interspersed with fantastical scenes that are more recognisable as the illustrator's imaginative work. My job involved checking artwork records, which often meant reading through pages and pages of information about landscapes, yet there was something about Sime's views that grabbed my attention. His softly dark forests under pink clouds were calming and quiet, yet had an overlay of something odd: a peculiar feature. Intrigued, I began to research Sime (and in 2014 was pleased to read a great article by Gallery Trustee, Mary Broughton).

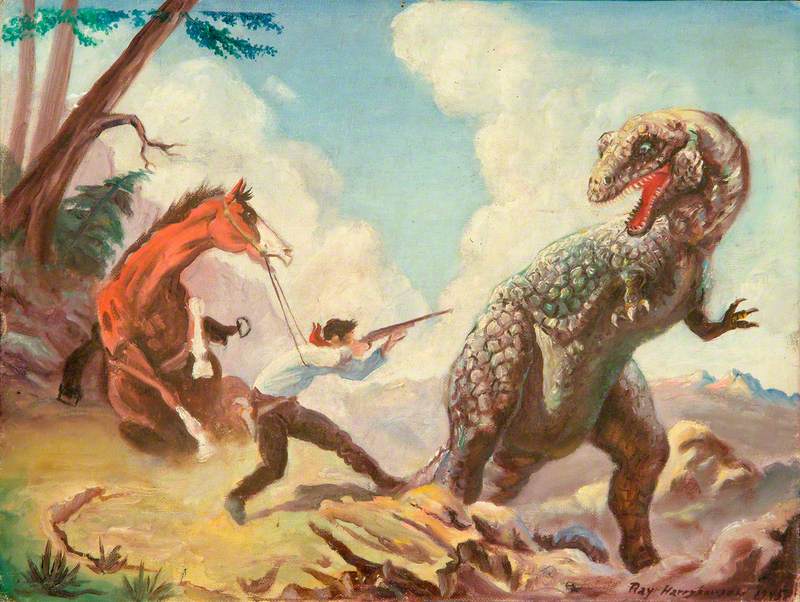

Sime spent years of his young life as a pit boy, scratching demons and imps on the pit walls to amuse himself. His artistic career started through sign painting and, after enrolling at the Liverpool School of Art, he gained awards and established himself as an artist, most famously the illustrator of Lord Dunsany's fantasy literature. Sime also painted Scottish landscapes and theatre scenery.

From his home in Worplesdon with his wife Mary, Sime continued to paint into middle age, interrupted by the First World War. In his 50s, the artist served as part of the Army Service Corps until he developed an ulcer.

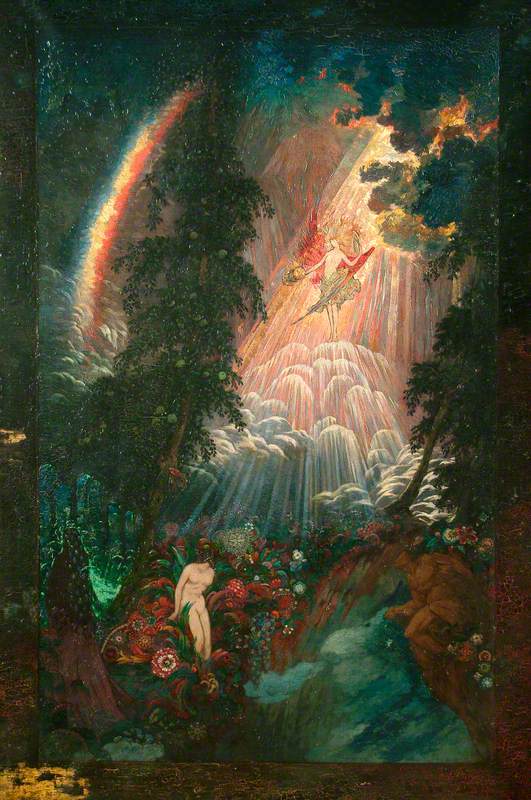

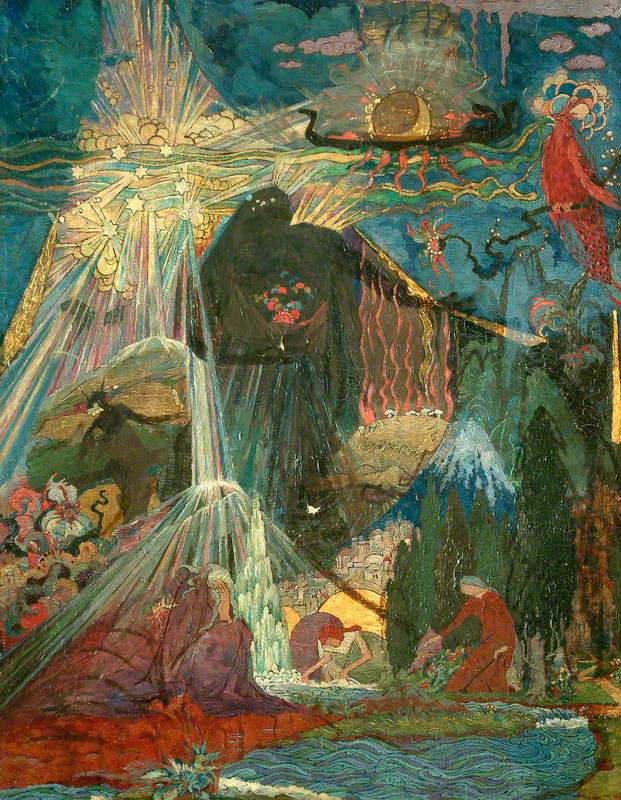

In later life Sime reputedly became more and more eccentric, obsessing over the Book of Revelation and painting apocalyptic visions. Desmond Coke said he had 'contempt for fame': the isolated Sime lived apart from the collaborative and consciously critical post-First World War art scene of the capital.

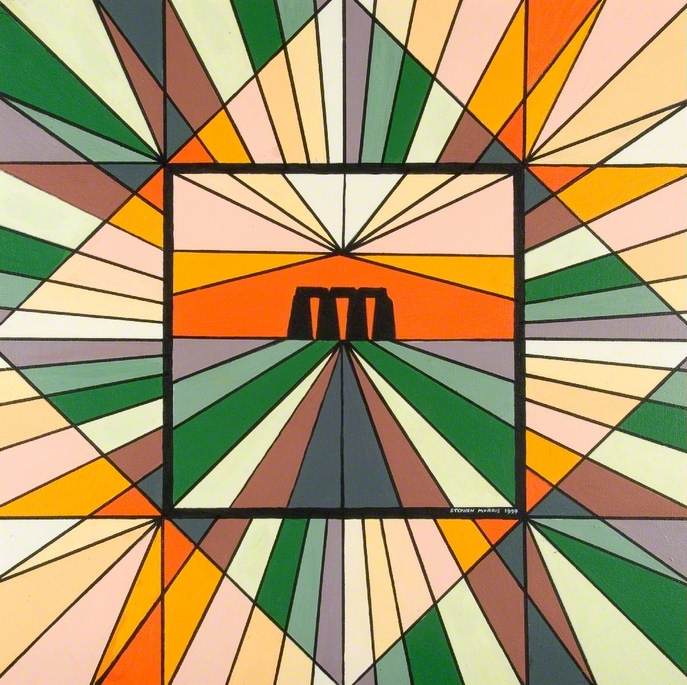

One can see a different mood in his work after the war, more illustrative, delving deeper into fantasy. Ultimately Sime's lasting legacy is a large and mysterious oeuvre, donated by his widow to the Gallery at Worplesdon. Though diverse, his caricature, fantasy and landscape work is united by an elegant line, and also frequently an intense attention to detail, featuring otherworldly figures and motifs. H. P. Lovecraft referenced Sime as a painter who can capture the 'beyond real', and fantasy artist Roger Dean – famous for his covers for the progressive-rock band Yes – also cites Sime as an influence.

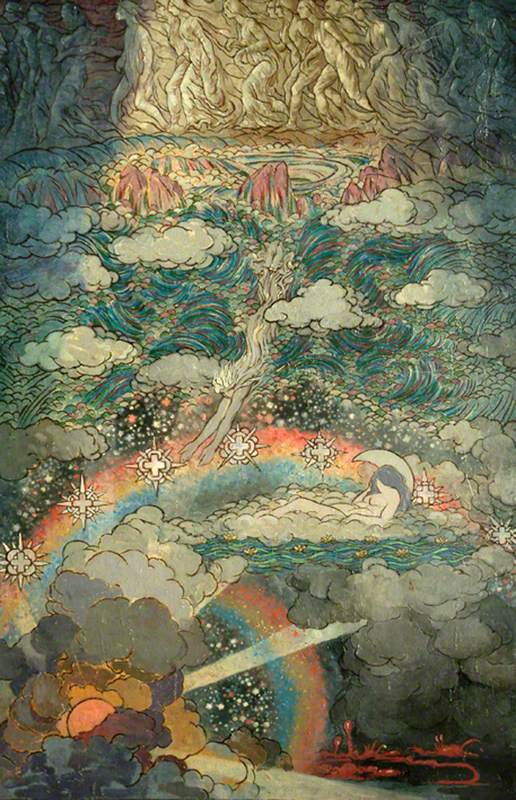

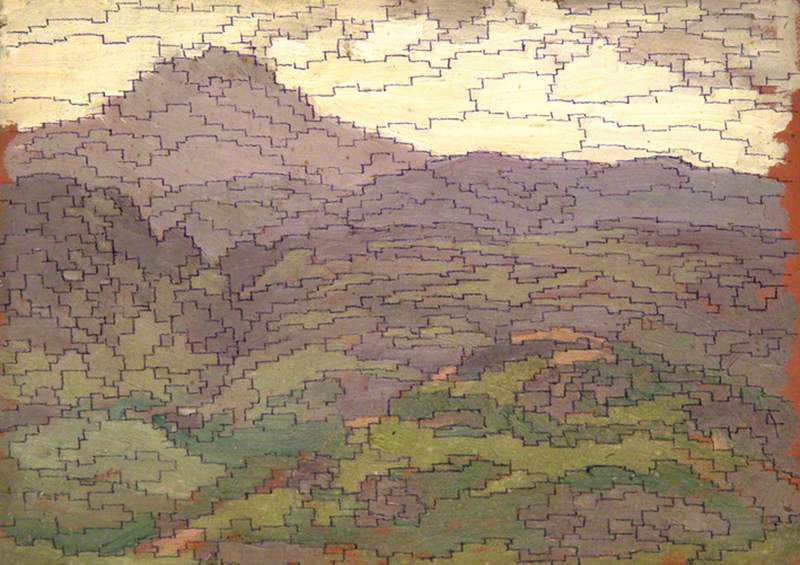

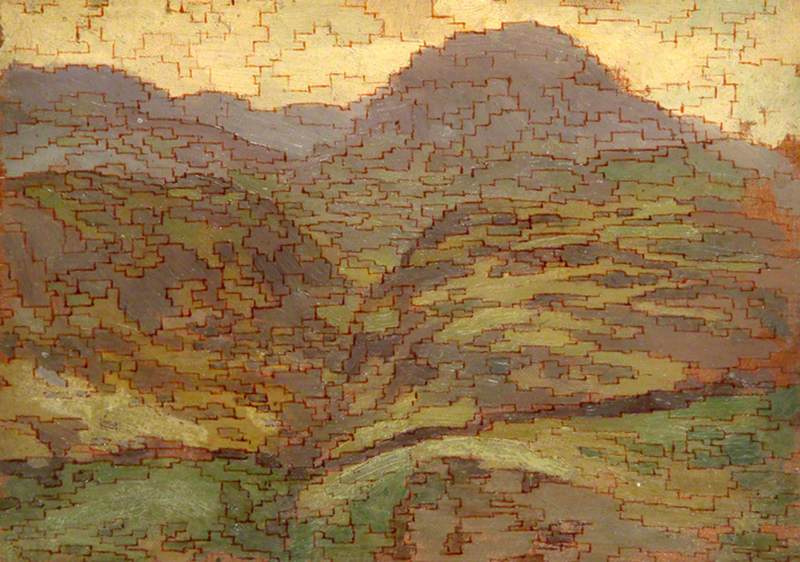

Becoming more and more interested in the eccentric artist, I began to create my own obsession with a particular element of Sime's work. Viewing the artworks in the database one after the other, I began to notice patterns and shapes hidden among the brushworks... Jagged, zigzag lines. What were they? Was the digital photograph corrupted?

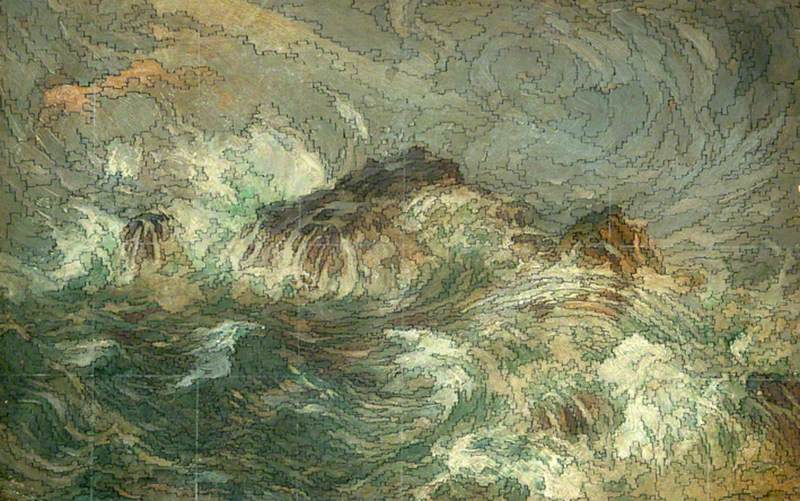

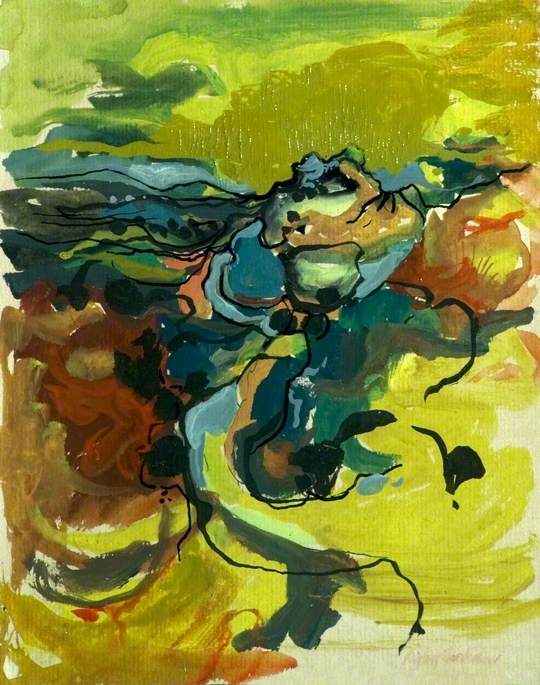

At closer inspection, I could see actual lines were painted over the landscapes, outlining clouds and trees. Did Sime paint these lines over his paintings because he saw shapes in the sky, trees and water? The 'patterned' works are undated, and titles given by curators: I wondered, did Sime paint these in his eccentric later life, at the time when he was obsessing over the Vision of Saint John the Divine and the Apocalypse? Would it be too farfetched to wonder if the paintings communicated Sime's glimpse of a 'divine order' in nature? I got a strange feeling looking at the digital image of Waves, which conveyed movement in hypnotic swirling colours.

I started to see the lines in more of his pictures, even hints of blocky brushstrokes in the dress of the Figure of Lady in White.

Was I getting carried away, seeking the mysterious? The thought nagged at me whenever I came across the artist, and so I

The Sidney H. Sime Gallery is in Worplesdon's Memorial Hall, just outside of Guildford. Worplesdon seems a quiet Surrey parish, imposing

Sime's art on display at Worplesdon Hall

Mary Broughton introduced me to the Gallery, a

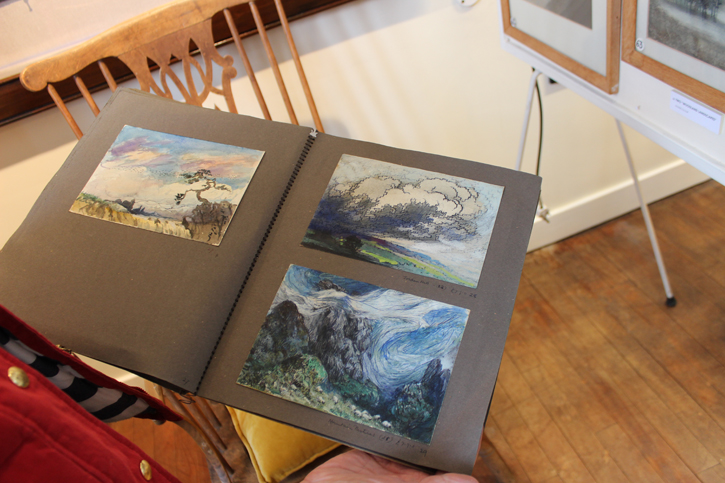

Sime's sketchbook

The archives contain many sketchbooks and folders, and looking through them I noticed scraps of familiar imagery, with patterns and scenes repeating in different pictures. Mary and I discussed Sime, his progression from pit boy to painter, and his works' inward quality.

Waves

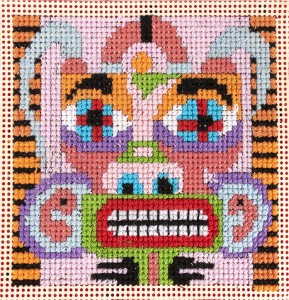

coloured paper squares by Sidney Herbert Sime (1865–1941)

I explained my fascination with the 'lines' in the landscapes. In Mary's article, she mentioned mosaics: were the patterns simply plans for mosaics and not the 'divine vision' I fancifully imagined? We looked at two small mosaic works in the gallery, made of tiny

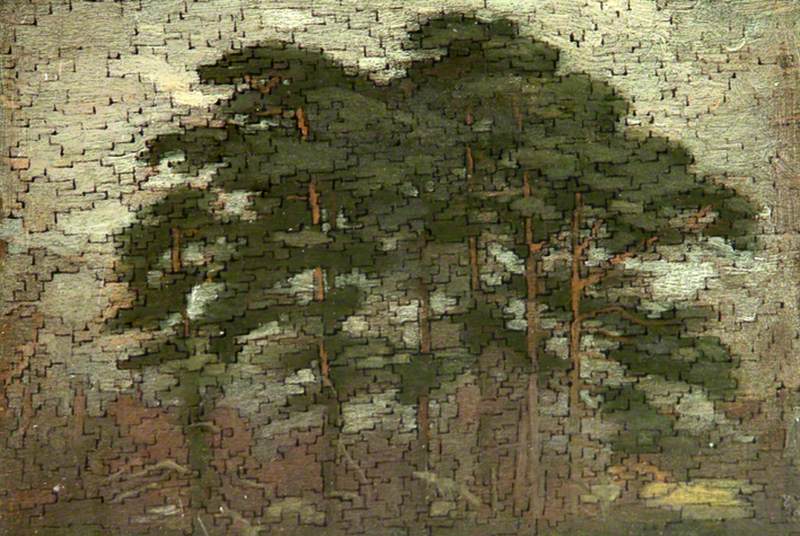

Focusing on select works, I can create my own theory: an imagined timeline of the progression from reality into fantasy, or vice versa. Some paintings show rosy sunsets over trees, cool mountains undulating into the distance, painted in simple daubs of colour yet predominantly standard. However in some landscapes, the 'lines' start to creep in: I can imagine Sime finishing a landscape, such as Dark Pine Trees, then afterwards adding the rough blocks around the shapes he had painted, perhaps even then reworking the colours back into the lines.

There are a whole set of mosaic-like landscapes where the dark outlines dominate the picture, perhaps even having provided the start of the painting process to be filled in afterwards. I would concede the patterned works are likely mosaic plans, if it weren't for one painting in particular that seems to show a link between Sime's real and fantasy worlds.

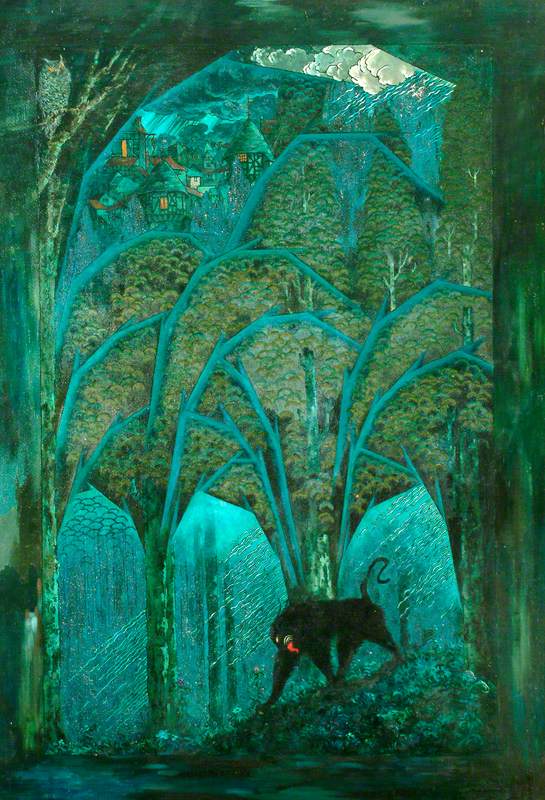

This painting, coincidentally, gave me another surprise when visiting the Gallery: Trees and Imps (titled by the collection).

Here, the blocky, rectangular lines morph into something tangible: strange dancing figures, with limbs and fingers cartwheeling through the trees. The figures fit alongside Sime's fantasy illustrations and even perhaps evoke his childhood pit sketches. When I saw this painting on the wall, the stab of recognition gave over to one of confusion – Art UK had photographed it upside-down! Having looked intensely at the picture (the wrong way up) on the database, I had assumed the figures, or 'imps', were hiding in the trees, but on the gallery wall it was clear that the pink cloud was the sky, and the figures on the ground. The imps had played a trick on me. Yet had they also provided the link between the lines and the landscapes, the real and the unreal?

Again, I was back to subjective speculation: trying to place Sime as an outsider, a mystic seer in the English folk tradition. I wanted to include Sime with the Neo-Romantic artists, along with Blake and later Nash, their work a visionary and emotional response to the English landscape threatened by invasion during the war.

Yet this is just one personal interpretation. Mary and I considered that in this case, interpretation is appropriate – Sime liked mystery, and above all, had a sense of humour. He might have liked that we were talking about him and making up our own stories. I haven't solved the mystery of the lines in the sky, but the Gallery in Worplesdon remains, full of secrets, waiting for curious people to come and make up their own minds.

Jade King, Art UK Senior Editor