The work of the late Scots-Ghanaian artist Maud Sulter (1960–2008), which wove together poetry and politics across form and discipline, exemplified both Charles Baudelaire's call for 'partial, passionate and political' forms of criticism, and American feminist Carol Hanisch's famous claim that 'the personal is political'.

Sulter's visual art was underpinned by deeply personal and political intentions, and was fiercely critical of the art historical erasure and omission of women and people of colour.

Her foremost objective was, in her words, to 'put black women back in the centre of the frame – both literally within the photographic image, but also within the cultural institutions where our work operates', and her work remains an incisive testament to these aims.

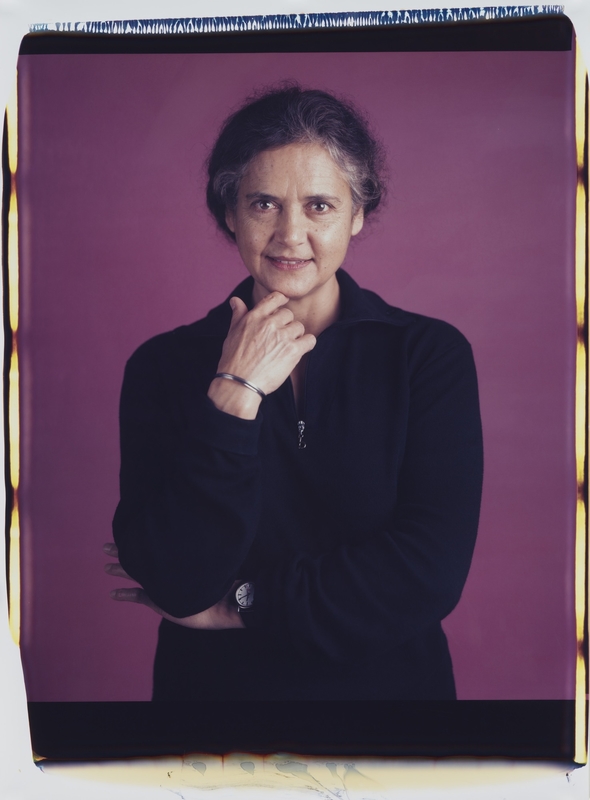

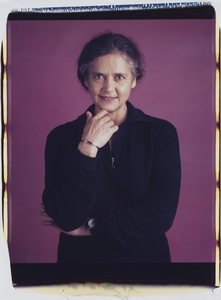

Maud Sulter at her exhibition 'Jeanne Duval: A Melodrama', National Galleries of Scotland, 2003

Born and raised in the Gorbals area of Glasgow, Sulter moved to London in her late teens to study at the London College of Fashion, though she maintained close links with Scotland throughout her career, and returned to live in the country in the last decade of her life.

From the 1980s onwards, Sulter's activity was remarkable in its diversity, and she proved to be a prolific and polymathic artist, developing a creative practice that spanned visual art, poetry, publishing, curating and teaching.

She first came to prominence in her twenties as an award-winning poet, winning an Arvon Foundation Residency in 1984 and, in 1985, the Vera Bell Prize for her first collection, As a Blackwoman.

Together with Caryl Phillips, the Arvon Residency was led by the Guyanese poet Grace Nichols. Seventeen years later, Sulter would photograph Nichols for the 2002 exhibition 'Beatrix Potter to Harry Potter: Portraits of Children's Writers', which was commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery.

Many of her final artworks in the 2000s were portraits of fellow poets and writers.

Sulter continued her work as a writer until her death, with many works published through her own imprint, Urban Fox Press, in the 1990s.

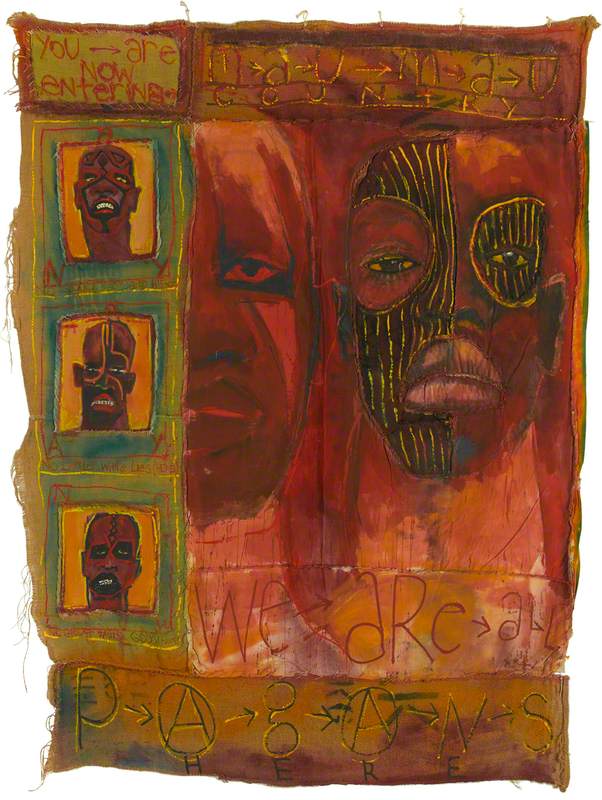

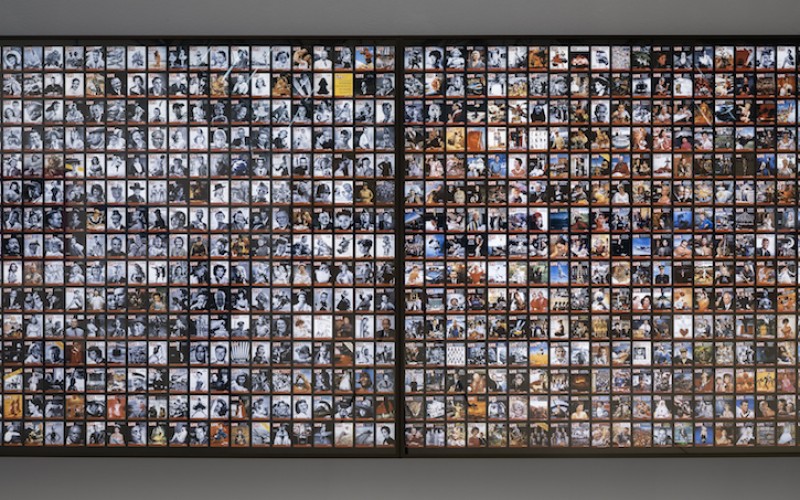

Text, as a visual form, had often featured in her artwork, from early collage works such as Poetry in Motion, exhibited in the ICA's groundbreaking exhibition of 1985, 'The Thin Black Line', to 1999's Scots w'Afro. However, from the late 1980s, extended narratives became an integrated aspect of many of her most celebrated bodies of work, often in the form of short plays or first-person narratives.

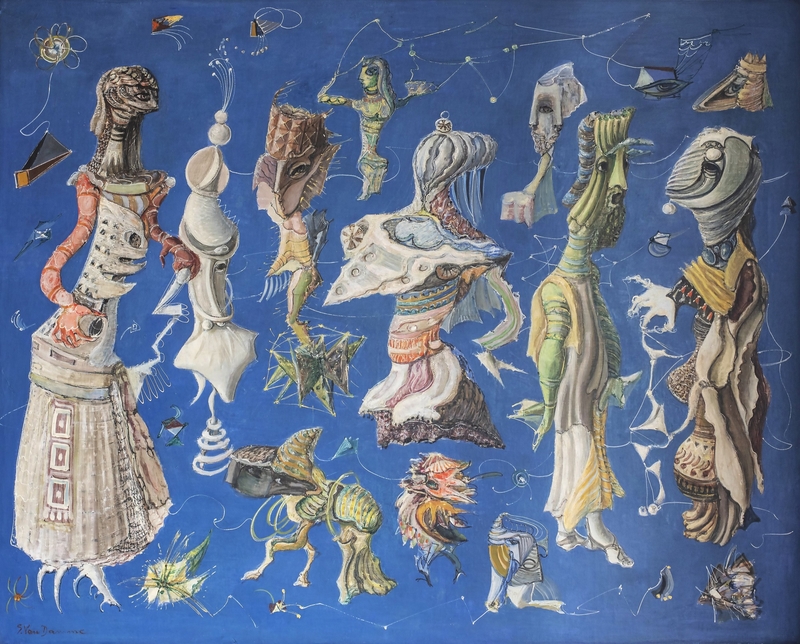

The 1989 photographic series Zabat, for example, was a collection of nine Cibachrome photographs of contemporary black women artists, musicians and writers depicted as a theatre of ancient muses. The works were accompanied by a book of poetry, Zabat: Poetics of a Family Tree, and a portfolio, Zabat Narratives, a series of nine prose poems, one for each portrait.

Together, the photographs and prose poems sought to celebrate the cultural accomplishments of black women, and to return agency and voice to historical muses who had been silenced.

In one of the nine works, the artist Dorothea Smartt becomes Clio, the muse of history, whose accompanying Zabat Narrative opens with a line from Alice Walker (who features in the same series): 'As a black person and a woman I don't read history for facts, I read it for clues.'

Clio continues: 'There is no story to tell that is more important than the story I tell you with my own lips, own tongue, own head. Clio is a woman with her head fixed assuredly upon her shoulders. Around her neck settle beads.'

In each of the nine images, the sitters carry their respective 'attributes', symbolic props held by allegorical figures as a way to decode their identity. As Phalia, for instance, Alice Walker carries flowers for the muse of comedy and bringer of flowers.

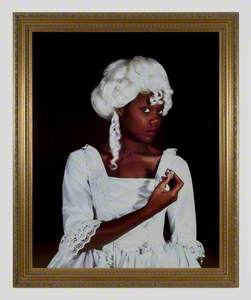

One of the most striking images in the series is the portrait of artist Delta Streete as Terpischore, the muse of dance and lyric poetry. Streete's costume was her own, created for her dance performance The Quizzing Class, which explored the relationship between enslaved women and their white mistresses.

Terpsichore holds a lump of fool's gold in her hands, an allusion to the legacy of colonial trade, slavery and servitude, while her elaborate white wig, associated with the enslaving class, overturns the conventions of eighteenth-century portraiture by centring a black subject.

Terpsichore

(from the series 'Zabat') 1989

Maud Sulter (1960–2008)

Created to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the invention of photography, Zabat demonstrated Sulter's ability to act as a champion, and advocate for her peers and contemporaries while exploring legacy and lineage through historical reference.

Implicitly, as with many of Sulter's lens-based works, the series also acted as a critique and inversion of photography's role in constructing and perpetuating colonial and sexist ideologies.

For Sulter, Zabat was a 'disaporan family tree', and her works between the mid-1980s and early 2000s are characterised by a recurrent concern with the African diaspora in European history and culture, and Sulter's own place within this legacy. Her autobiographical series of large-scale silver gelatin photographic prints, Significant Others, consists of enlargements of snapshots taken from Sulter's family archive.

Earlier this year, the University’s #BoswellCollection was delighted to acquire a series of 9 photographs entitled ‘Significant Others’, by Scottish Ghanian artist Maud Sulter (1960-2008).

— Museums of the University of St Andrews (@MuseumsUniStA) July 20, 2020

Here are three of our favourites. pic.twitter.com/0hhQg3qoXo

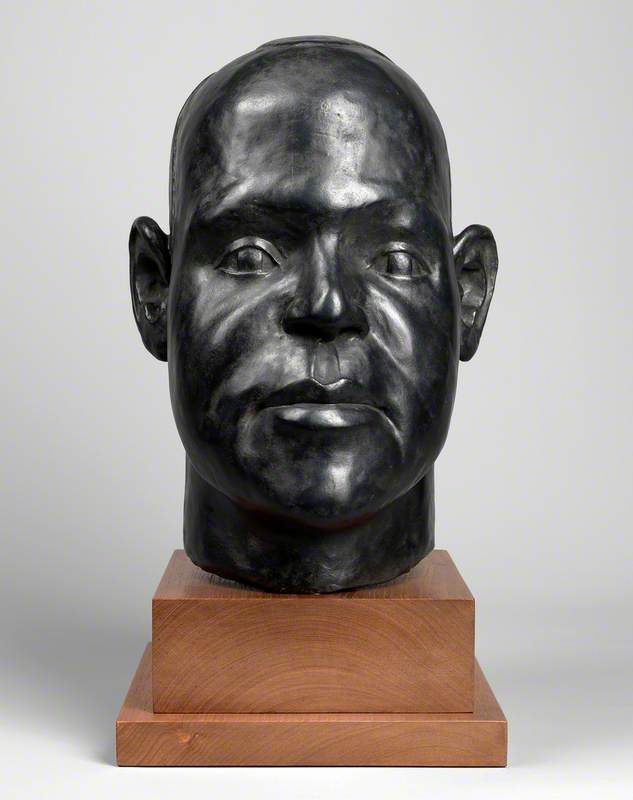

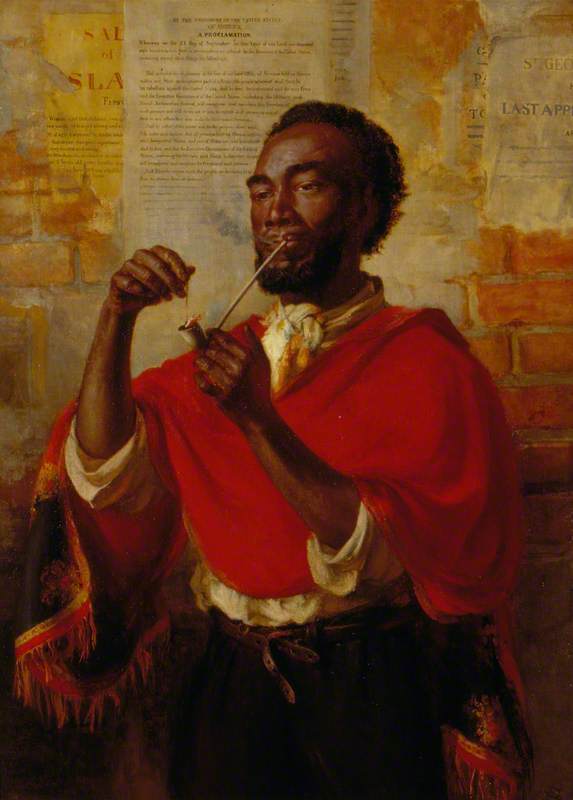

Other works feature late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century black writers and artists such as Edmonia Lewis (in 1991's Hysteria), Alexandre Dumas (in 1993's Syrcas), and, most frequently, Jeanne Duval, the late nineteenth-century, Haitian-born actress, model and dancer most famously known as the mistress of Charles Baudelaire and muse to Manet, Courbet and other artists.

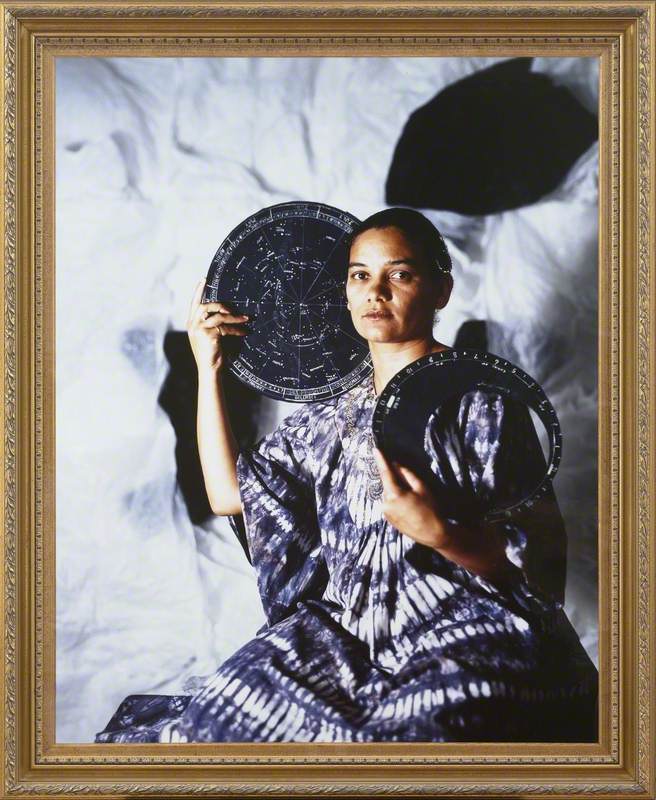

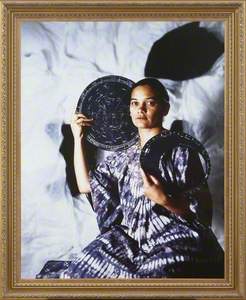

Calliope

(from the series 'Zabat') 1989

Maud Sulter (1960–2008)

In Zabat, Sulter's self-portrait shows the artist in the guise of Jeanne Duval as the muse Calliope. In his 2007 book Scottish Photography, the art historian Tom Normand describes the work as one that 'looks like an academic painting, but is manifestly a photograph, a photograph which contains many subtle allusions', including, compositionally, a reference to Nadar's famous 1864 portrait of the actress Sarah Bernhardt.

Following Zabat, Sulter returned again and again to the figure of Jeanne Duval in Duval et Dumas (Syrcas, 1993), Jeanne: A Melodrama (1994) and Les Bijoux (2002).

Sulter often worked collaboratively on large, ambitious projects alongside artists and writers such as Ingrid Pollard, Marlene Smith, Bernadine Evaristo, Dionne Sparks and, most frequently, her partner, the artist Lubaina Himid, who shared her aim to 'fill in the gaps of history' through the reinsertion of black narratives into art and culture.

In Zabat, Hysteria and other works, her friends and peers appeared as models, subjects and sitters. Sulter's works of the 1980s and 1990s were resolutely feminist and actively anti-racist in both form and content.

In some, Sulter appropriated the formal language of visual dissent (the echoes of Hannah Höch and John Heartfield in Syrcas, for example), while elsewhere, including in Zabat, Sulter's use of photography as a medium was deliberate, a subversive deployment of the very tools used to construct the colonial gaze.

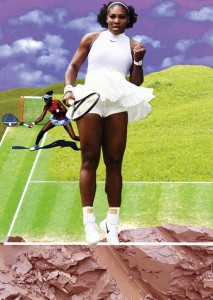

In her late works of the 2000s, Sulter appeared to have moved towards more conventional portrait photography. But even here, the artist's stated aim 'to put black women back in the centre of the frame' is subtly apparent.

In the six commissioned portraits of children's authors for the 'Beatrix Potter to Harry Potter: Portraits of Children's Writers' exhibition, three are of women of colour (Grace Nichols, Jamila Gavin and Malorie Blackman), and a fourth is of the children's poet John Agard.

While ostensibly 'conventional' in form, both here and in ten portraits of Scots poets, commissioned by the Scottish Poetry Library in 2002, Sulter continued to experiment formally.

Measuring 20 inches by 24 inches, the Polaroid portraits were taken on a unique machine sourced in Prague, which allowed the artist just one shot at composing her portraits. In this way, Sulter again undermined the rules of the medium by using a form invented as a way to record an instant 'snapshot' to produce a body of work that functions as a permanent, lofty record of cultural achievement.

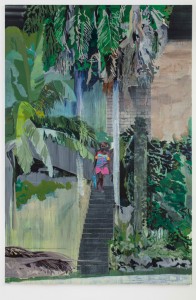

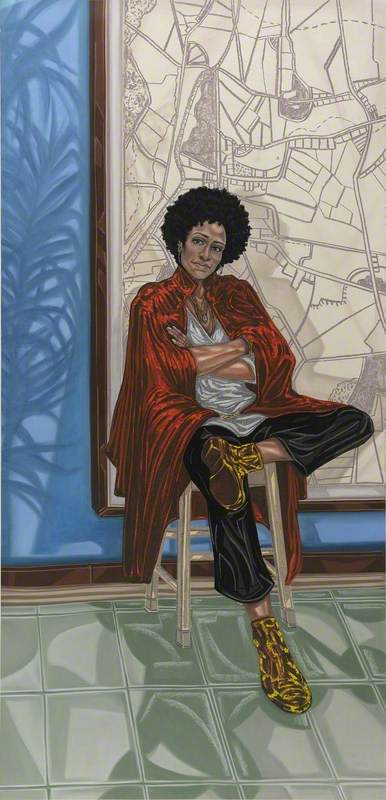

In 2002, Sulter produced two portraits of broadcaster, playwright, critic and columnist Bonnie Greer during the making of a BBC Four television programme, Reflecting Skin, which explored the image of black people in Western art.

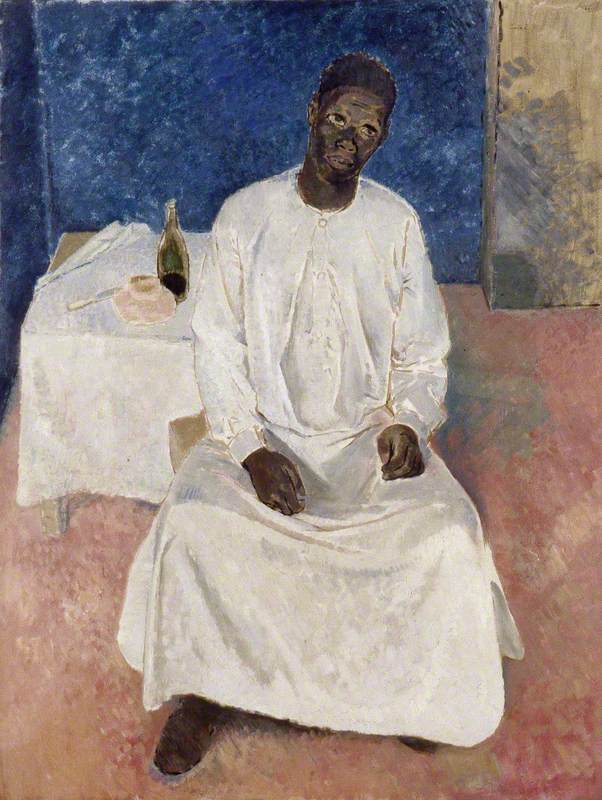

One of the two portraits, a colour Polaroid, posed Greer as 'Madeleine' in Marie-Guillemine Benoist's 1800 painting Portait présumé de Madeleine (formerly known as Portrait de négresse), held by the Louvre.

The compositional approach, essentially a photographic restaging of the Benoist work, echoed Sulter's approach in self-portraits such as Jeanne Duval in Calliope, and her reimagined life of Edmonia Lewis in Hysteria, which drew on images of Lewis in carte de visite photographs taken by Henry Rocher.

As one of Sulter's last works, Bonnie Greer is manifesto-like in its commitment to present a black woman as the central aesthetic subject, a role canonically reserved for white women in figurative painting. It also reflects Sulter's interest in art historical works by women, a theme she had explored as a curator in her 1991 exhibition 'Echo: works by women artists' at Tate Liverpool.

With the portrait of Greer, Sulter demanded more from her portraits than a simple record of the sitter, just as she had over a decade earlier in Zabat. Not only is this an image of Greer, it also celebrates the original model, Madeleine, a formerly enslaved woman from Guadeloupe who was a servant in the household of the artist's brother-in-law.

Implicitly, it pays homage to Benoist, a woman who, like Sulter, defied artist convention, and it exemplifies the characteristic melding of painting and photography in Sulter's iconic works, where so many appear as if they were stills from a tableau vivant.

Sulter's poetic politics are perhaps epitomised by Terpischore's words in Zabat Narratives. They serve as a fitting reminder of Sulter's ambition and her lasting legacy: 'Transmitting our stories by word of mouth does not possess archival permanence. Survival is visibility.'

Susannah Thompson, writer and art historian

This content was supported by Creative Scotland