For my tenth birthday, I received a portrait of Walter Scott. I wasn't expecting it and gasped when it fluttered out of a birthday card from my Granny. I picked it up and held it to the light – couldn't quite believe it was all mine: a crisp, blue £5 note, fresh from the Bank of Scotland, bearing an engraving of the famous writer. I was rich!

Sir Walter Scott on the Bank of Scotland £5 note

Today, the banknote shows the best-known painting of Scott, by Sir Henry Raeburn. This year marks 250 years since the birth of the man on the money: the poet, novelist and antiquarian who once dominated literary culture, just as his great monument towers over Edinburgh.

In his day, Scott outsold his contemporaries Lord Byron and Jane Austen. His book-length poem of 1810, The Lady of the Lake, kickstarted literary tourism, sending thousands of view-seeking visitors to the Trossachs, as captured by John Knox in his painting Landscape with Tourists at Loch Katrine.

Waverley, Scott's debut novel, gave its name to the capital's railway station. When Scott switched from poetry to novels, Austen wrote: 'It is not fair. He has fame and profit enough as a poet.' In 1814, Waverley is reported to have sold more than every other novel published that year. With that novel, whose subtitle was Tis Sixty Years Since, Scott helped to invent the genre of historical fiction.

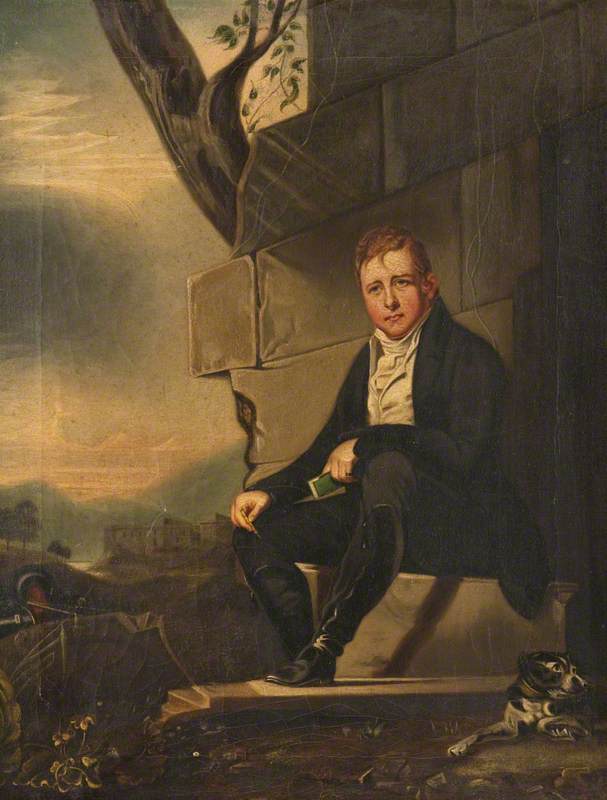

Sir Walter Scott Finding the Manuscript of 'Waverley' in an Attic

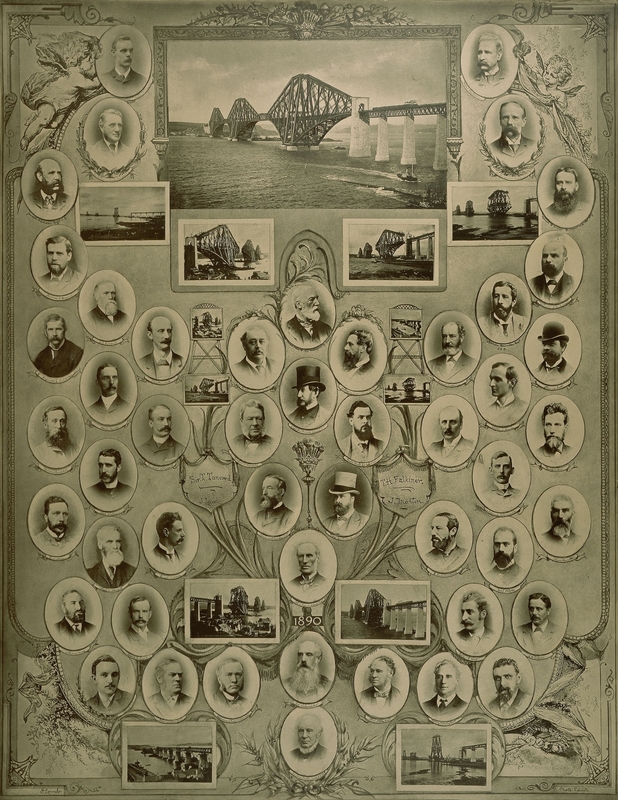

1890

Charles Martin Hardie (1858–1916)

His romantic epics of noble clans, bloody battles and doomed love moved Schubert to compose Ave Maria, and Donizetti to write Lucia di Lammermoor – only Shakespeare has inspired more operas.

The nineteenth century is rich with depictions of Scott, his characters and Abbotsford, the eccentric castle he built in the Borders (giving rise to the Scots Baronial style). I've been reappraising the man, his world and his work for a BBC documentary marking his 250th birthday, In Search of Sir Walter Scott.

A View of Abbotsford from across the Tweed

1828

Elizabeth Wemyss Nasmyth (1793–1862) (possibly)

My birthday fiver is long gone – on what, I sadly don't remember – but a slightly stern Scott still looks out from every single Bank of Scotland note: from the lowly fiver to the oft forged £50, and the rarely seen £100. That's because, in 1826, Scott led a campaign to preserve the rights of private banks, including those in Scotland, to print their own notes of whatever denomination.

Writing under a pseudonym – as he very often did – one Malachi Malagrowther argued for a 'national choice'. Scott's alter ego succeeded, and a grateful Bank of Scotland put his face on their money. To this day we carry him around in our pockets, if we're lucky.

This must make Henry Raeburn one of the world's most reproduced artists, and Scott one of our most recognisable writers. And yet, for all this familiarity, Scott is rarely read now – his fame has dimmed, his books gather dust. In my nearly two decades of interviewing other writers, not one has ever cited him as a favourite. Burns, endlessly. Scott, never.

The Meeting of Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott at Sciennes Hill House

1893

Charles Martin Hardie (1858–1916)

Literary fashions change, and Scott's politics (High Tory, avowedly pro-Union and generally patrician) no longer hold sway in the homeland he so passionately put on the map. The author of Trainspotting, Irvine Welsh, who reimagined Edinburgh centuries after Scott, embodies contemporary suspicion: 'I dislike the Walter Scott crawling-up-the-Prince-Regent's-arse-for-patronage tartan minstrel commodification of Scotland.'

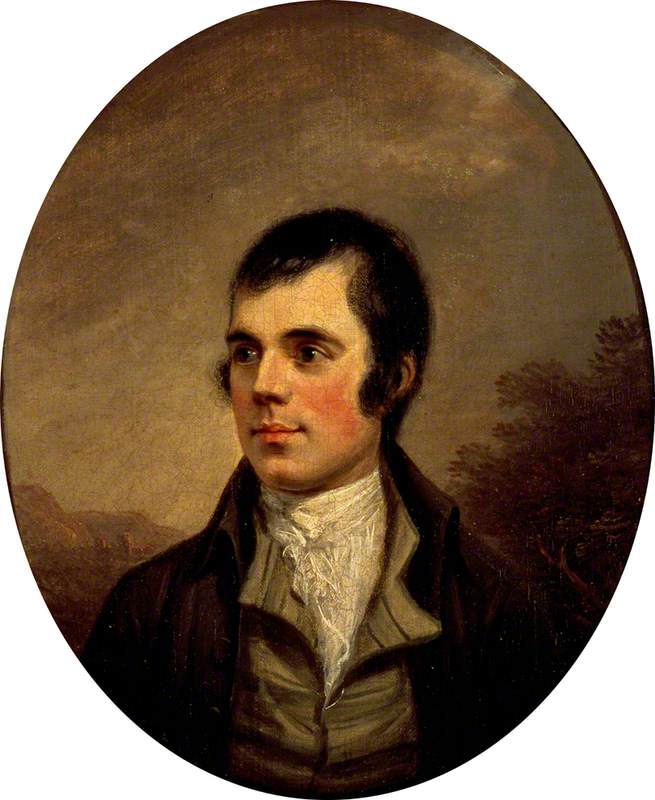

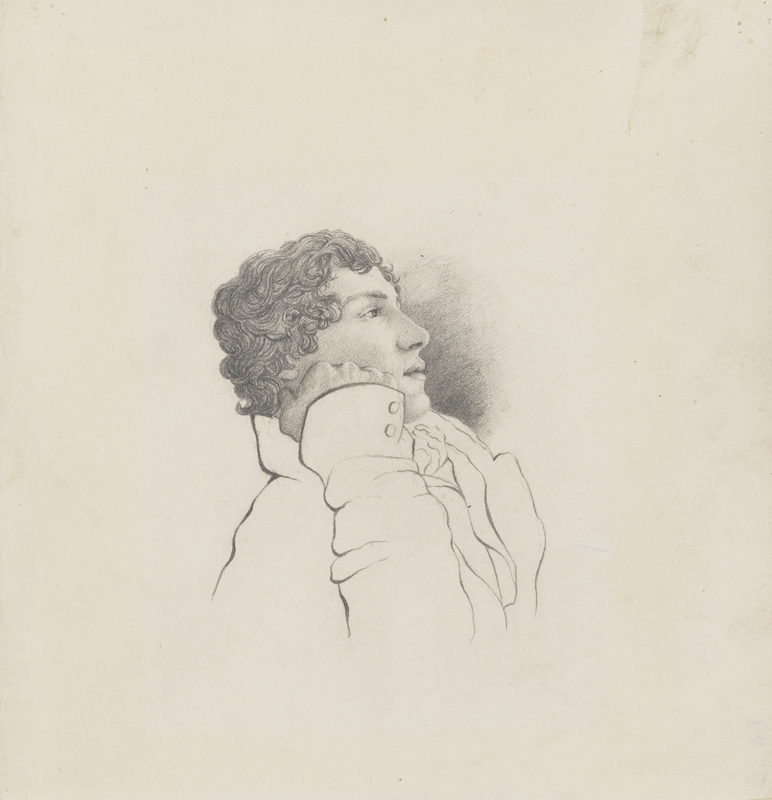

Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832), Novelist and Poet

1822

Henry Raeburn (1756–1823)

While making my documentary about Scott, I visited the original Raeburn, held by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, and, sadly, at the time of writing, in storage. It's a simple, even noble, composition: Scott, head and shoulders. A light, no doubt of literary genius, illuminates Scott's face and he's looking up, perhaps for inspiration. He is wearing what seems to be the same yellow waistcoat he's got on for the Edwin Henry Landseer portrait in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in London.

A thick, woven gold watch-chain tells us he is rich. There are no inky fingers, there is no quill. There are no books or papers. There is only the man. And that's because he was so famous, so instantly recognisable, he needed no props or context. Which is why Raeburn wanted to paint him – this was to be a calling card for lucrative commissions. It is Raeburn's third portrait of Scott – of the others, Scott said, with characteristic self-effacing humour, 'he has twice made a very chowderheaded person of me'.

Lady Scott, née Charlotte Margaret Charpentier (1770–1826)

c.1805

James Saxon (1772–c.1828)

It was also the last picture Raeburn ever painted. Neither Raeburn nor Scott knew what was coming. As part of his research, Raeburn went out walking in a very rainy Fife with Scott who, despite childhood polio, was an inveterate pedestrian. Raeburn got a chill and was dead soon after. Not long after that, Scott's wife, Charlotte, died. And then his fortunes took a hit during the financial crash of 1825. Scott spent the rest of his 61 years writing every day to stave off bankruptcy and save his beloved Abbotsford.

Scott's death, at Abbotsford in 1832, made headlines around the world. The city and citizens of Edinburgh raised funds for a monument as great as his cultural contribution, and it still stands on Princes Street today. Completed in 1844, it looks like a giant Gothic rocket. I have never dared climb the 287 steps to the top. Like his books, the tower is stuffed with characters, real and imagined, all cheek-by-jowl.

There are 64 statues adorning it, not counting Scott and his dog. They include Mary, Queen of Scots, James I and James V, and also icons of Scottish literature – James Hogg, Robert Burns and Allan Ramsay – along with other writers, including Lord Byron. You can also spot characters from Scott's own novels including Rob Roy, Ivanhoe and Guy Mannering.

There are 32 unfilled niches at higher level, and it's interesting to wonder who among all the writers and characters Scotland has produced since, Scott might choose to fill those spots. The statue of Scott and his beloved deerhound Maida was made by Sir John Steell (seemingly baronets only liked to be depicted by other baronets).

Edinburgh is littered with Steell: Allan Ramsay is a bit further down Princes Street and the Duke of Wellington, on his horse, is within waving distance. Steell's Scott is swathed in a toga like some latter-day Plato. He appears to be resting from writing and is holding a quill while waiting for inspiration to strike. I hope he didn't get ink on the toga. He looks suitably mournful.

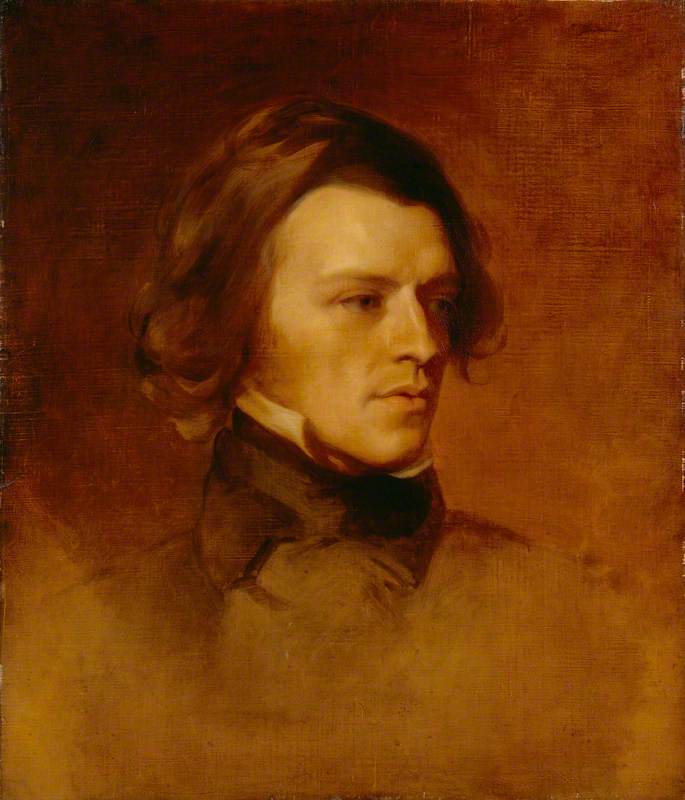

Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832)

1820

Francis Leggatt Chantrey (1781–1841)

Revisiting Scott for the first time since school, and discovering his journals and letters, introduced me to a personality much less forbidding, and far more approachable, than the man on the money or the legend in the monument.

My favourite encounter with Scott is coming nose-to-nose with the marble bust made by Francis Leggatt Chantrey, versions of which can be found in numerous collections on Art UK. Today, the bust sits in the alcove of honour in the library at Abbotsford, but when Scott was alive, that spot was occupied by Shakespeare, who now sits across the room.

Bust of William Shakespeare (1564–1616)

(after Gheeraert Janssen) 1814

George Bullock (1778–1818)

This, again, is typical of Scott's reverence for those who went before him, and also of his own modesty. This bust shows Scott with his head tuned slightly to the left, as if you've just asked him a question he's about to answer. A lowland plaid is arranged around his shoulder – important, as he helped to rehabilitate the wearing of tartan after Highland dress had been outlawed.

Those who knew Scott felt the bust captured his character. Hogg wrote that 'Sir Walter Scott in his study, and in his seat in the Parliament-house, had rather a dull, heavy appearance, but in company his countenance was always lighted up, and Chantrey has given the likeness of him there precisely'. Scott liked it too, saying: 'Ay ye're mair like yoursel now! – Why, Mr Chantrey, no witch of old ever performed such cantrips with clay as this.'

Chantrey's Scott has the trace of a smile, he invites us to lean in and listen to a story. Now, 250 years on, that story is fainter, but still well worth a listen.

Damian Barr, writer, broadcaster and journalist

This content was supported by Creative Scotland

In Search of Sir Walter Scott, produced by Factory Films, will be broadcast on BBC Scotland and available on BBC iPlayer from 10th August 2021.