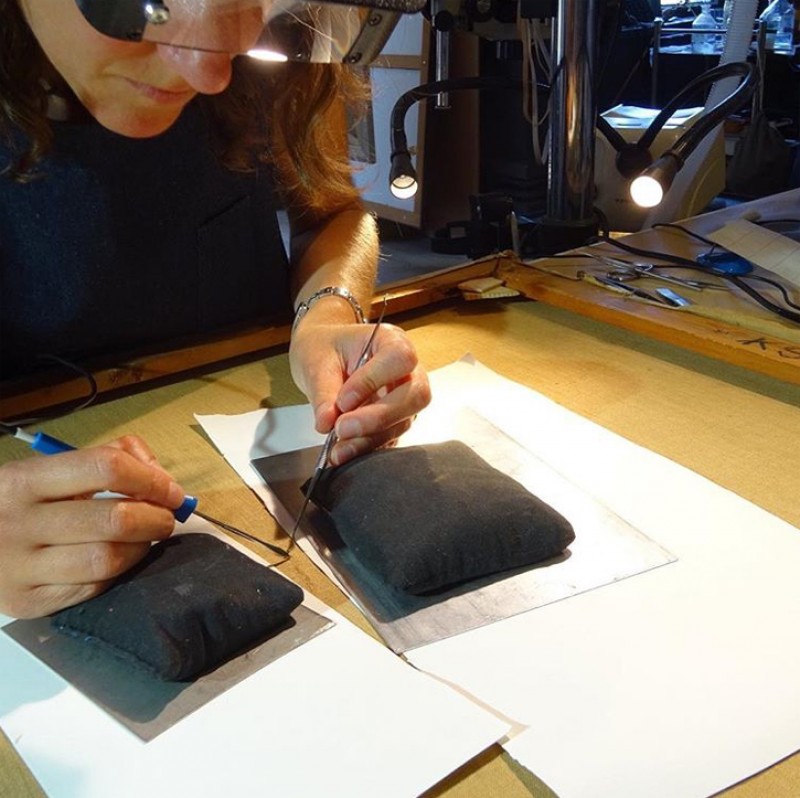

In this series, 'Conservation in focus', Simon Gillespie, Director of Simon Gillespie Studio, explores the art of conservation. In each article, Simon looks in depth at a particular technique or tool that is crucial to conservators and explores the challenges – and triumphs – associated with their everyday work.

In the last article, I discussed some of the ways in which my eyes are my most useful tool as a conservator. Here I will list some types of light that help conservators to see different aspects of a painting.

Strong light

Good, strong lighting is very important for the process of visual examination: for example, in dim lighting anyone might walk past the portrait of George Oakley Aldrich in the Bodleian collection without a second glance, dismissing it because of its dirty dulled appearance, the ink spatters, soot from wood-burning stoves and dust from hanging for centuries in a library.

The portrait of George Oakley Aldrich during treatment, showing surface dirt being removed

But a bright light shining at the painting could pierce through the dust and the cloudy discoloured varnish to reveal what lay beneath: a painting of great quality, in which the texture of the fur popped out and the sitter came to life. It showed us that this was a worthwhile project of great promise and gave us a hint of the quality that would be revealed by conservation treatment.

George Oakley Aldrich (1721–1797)

c.1750

Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787) (attributed to)

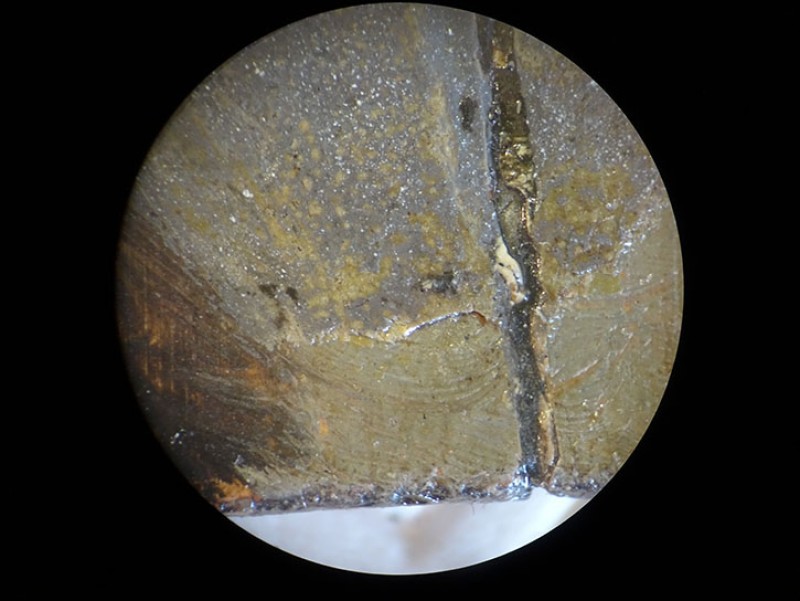

Raking light

Looking at a painting in 'raking light' simply means looking at it with the light shining from an acute angle rather than from the front, so shadows will be cast where the surface is not perfectly smooth. It is useful for showing up structural issues, such as paint that has cracked and is lifting away from the support, damage or past repairs to panel paintings creating an uneven surface, or any bumps and lumps in the canvas where the fabric has suffered a knock or where there is debris that has fallen behind the stretcher bars and is pushing the canvas out.

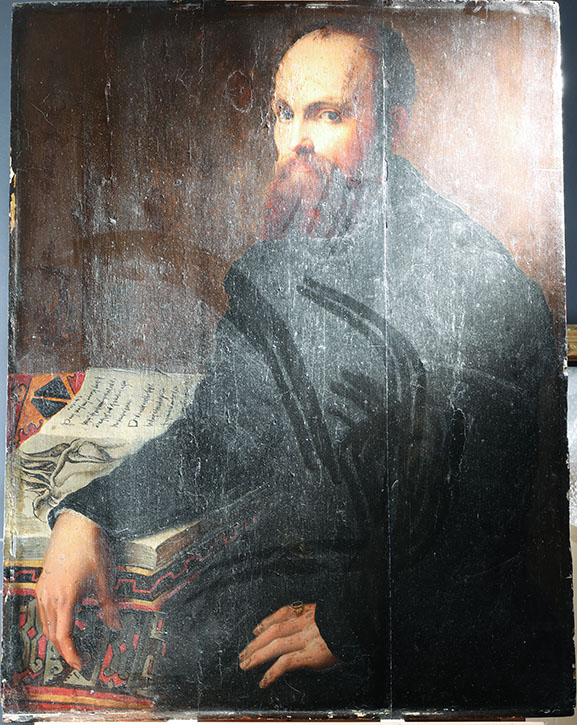

When the portrait of Realdo Colombo by Francesco Salviati (then known as 'A Physician, Italian (Florentine) School') first arrived at the studio from Tatton Park, observation in raking light showed that not only was it covered in smears of air-borne dirt, there was a step in the panel where two planks of wood had been poorly joined, and there were areas where damage to the artist's paint layer had been poorly filled and retouched, leaving a dip and different texture to the original surface.

Realdo Matteo Colombo (1515–1559)

1530–1569

Francesco Salviati (1510–1563)

Another example is when I went to see the Titian at Petworth: the poor quality of the bottom section of the painting, and in particular the sitter's fingers, struck me when compared with the high quality of the face and the Titianesque characteristics of the eyes.

Shining a torch at an angle showed me that the bottom section of the painting was, in fact, a separate strip of canvas which had been stitched on. The difference in the quality of painting on this strip suggested that this was not the original artist's work.

When examining the panel of Balthazar under raking light on its arrival from Brighton & Hove Museums, I immediately noticed a serpentine shape of the top, suggesting that this painting was once one of the wings of a triptych altarpiece. Balthazar would have been on a side wing, facing the middle of the scene. At some point in the history of the artwork, the panel depicting Balthazar had been separated from the rest of the triptych and an insert had been added to the top of the shaped panel to make it rectangular. The insert is especially visible in raking light.

A conservator's eyes are their most used tools, but there is also specialised equipment which allows us to look beneath the surface of a painting and reveal things unseen to the eye: I am, of course, thinking of x-radiographs, infrared, and ultraviolet light. In the next article, I will explore how we use these.

Simon Gillespie, Director at Simon Gillespie Studio