What do you think of when you picture a nurse? Starched uniforms or scrubs? A stern or saintly demeanor?

The image of a nurse has changed over time, just as the job has evolved from informal necessity to scientific profession. Nursing was often dismissed as a menial profession until the work of nurses during the Crimean War generated valiant, idealised depictions of nurses that lasted through the wars of the twentieth century.

St Mary's First Aid Post by Candlelight

1941

Anna Katrina Zinkeisen (1901–1976)

As one of the few roles initially open to women, views of nursing became strongly gendered in the UK and many other western countries. Because of this, depictions of nurses in art also reveal shifting attitudes towards women's roles – including stereotypes that sexualised or sought to diminish women in positions of power – and assumptions about women bearing the burdens of care.

As of March 2021, over 300,000 nurses were working for the NHS. But the challenges of the global pandemic have created ever more intense demand and stresses on healthcare workers. The ways we represent nurses in art signify how we celebrate or gloss over some of the most vulnerable aspects of being human: providing care through illness, war, and death.

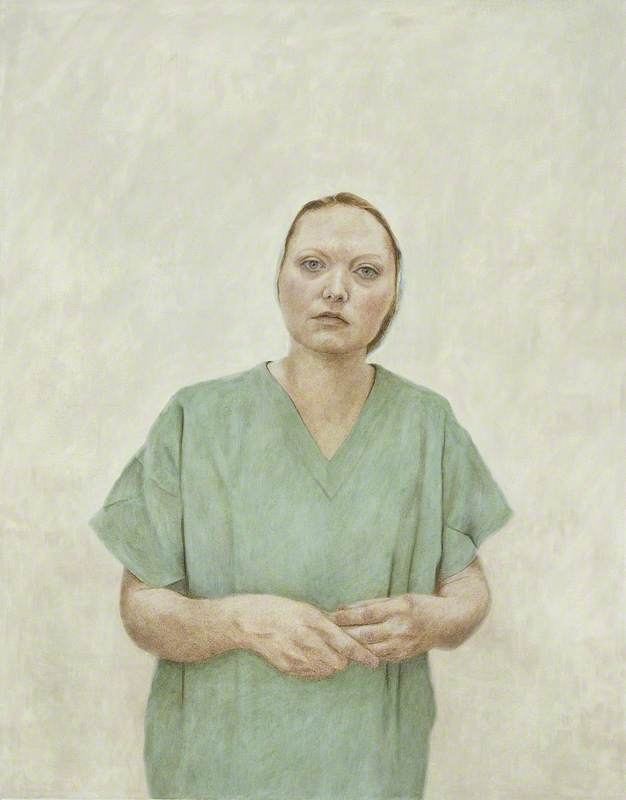

A Nurse Monitoring a Patient after an Operation and Taking Notes

1995 (?)

Virginia Powell (b.1945)

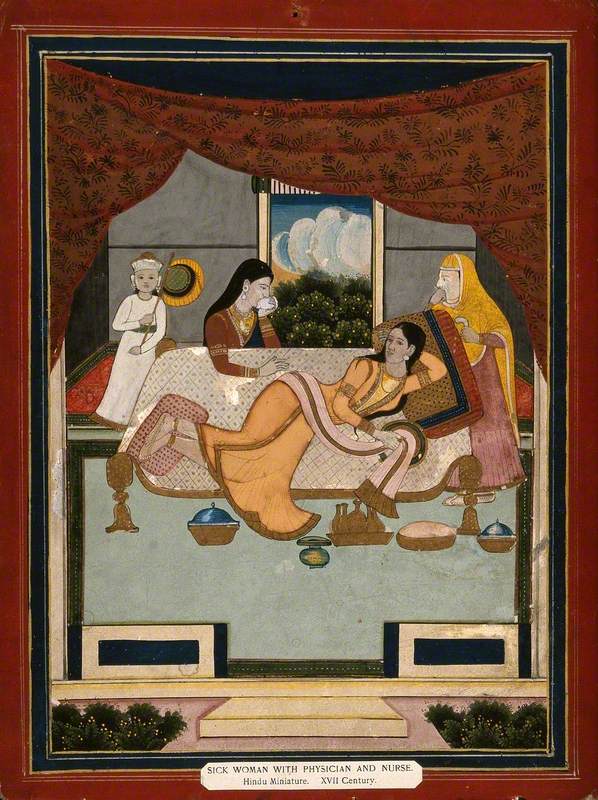

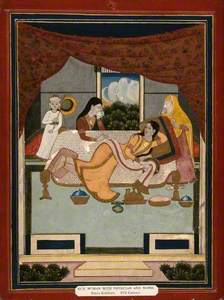

Nursing before Nightingale

Nursing is an ancient profession: the earliest known nursing school, which only accepted men, dates from 250 BC in India. The English term is derived from wet nurses who breastfed infants, but the role soon expanded beyond its associations of childcare to providing care for the sick and injured.

Through the medieval and early modern eras, both men's and women's religious orders were known for tending the sick as an act of charity, some becoming dedicated nursing orders (like the order later fictionalised in the popular series Call the Midwife). Religious artwork tended to focus on images of divine healing, but some images also depicted care for sick and suffering individuals, like a 1440 fresco cycle in the Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena.

The Good Samaritan Attending to the Wounded Traveller at the Inn

Giovanni Battista Langetti (1635–1676)

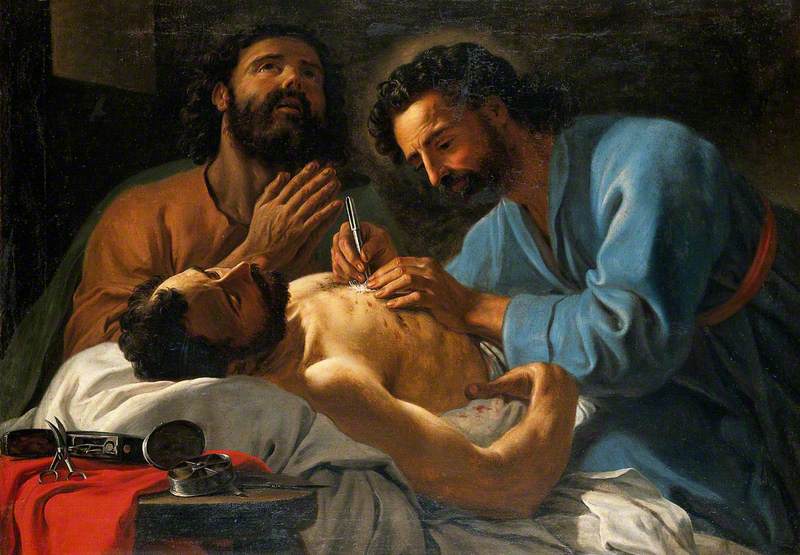

The moral imperative to provide compassionate care was underscored in depictions of Biblical parables, like this seventeenth-century painting of the Good Samaritan who selflessly cared for a wounded traveller, or a 1748 work depicting Saints Cosmas and Damian dressing a chest wound.

Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian Dressing a Chest Wound

1748

Antoine de Favray (1706–c.1792)

Early nursing was informal, and most people were cared for at home by relatives, local healers, or servants if they were wealthy. Jacobus Vrel's The Little Nurse shows the quiet forbearance of a domestic nurse in the mid-seventeenth century, their bedridden patient just out of sight.

Understandably, nursing care could be uneven based on differing levels of wealth and access. Though many patients were nursed back to health, paid nursing became associated with a poor quality of care and was seen as a menial job for impoverished or elderly women. Since it involved intimate care for the body, it was also treated as adjacent or akin to sex work: the opposite of the era's ideal of sheltered womanhood.

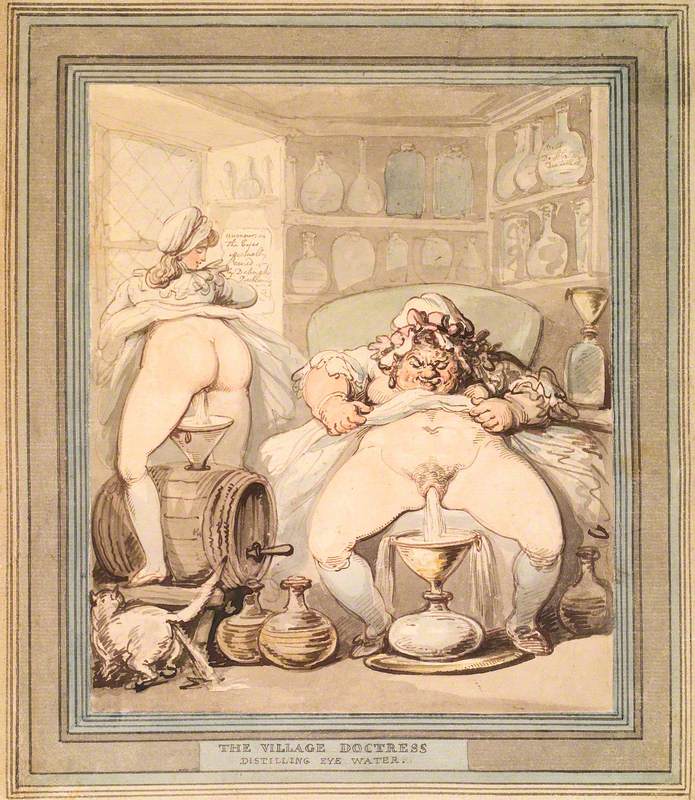

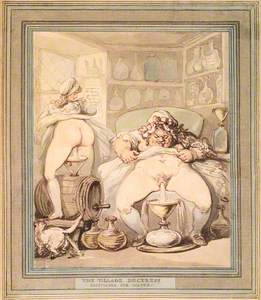

The Drunken Nurse

late 18th C–early 19th C (?), watercolor on paper by Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827)

Images of drunken or slovenly nurses perpetuated in Georgian caricatures like Thomas Rowlandson's watercolour of The Drunken Nurse, and the dissolute character of Sairey Gamp introduced in Martin Chuzzlewit in 1844 became emblematic of this stereotype.

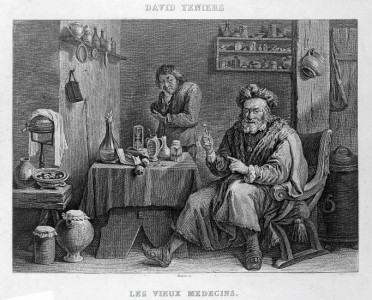

Another c.1800 Rowlandson caricature shows a 'doctress' making eye medicine. While intended to mock 'snake oil' treatments, showing the woman and her assistant urinating to create a cure, his depiction also cruelly demeans the knowledge of village healers. The Enlightenment's emphasis on scientific hierarchies often dismissed the informally accumulated expertise of nurses and midwives.

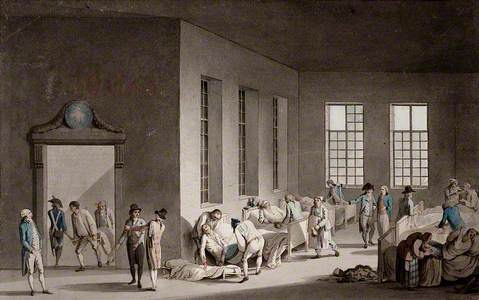

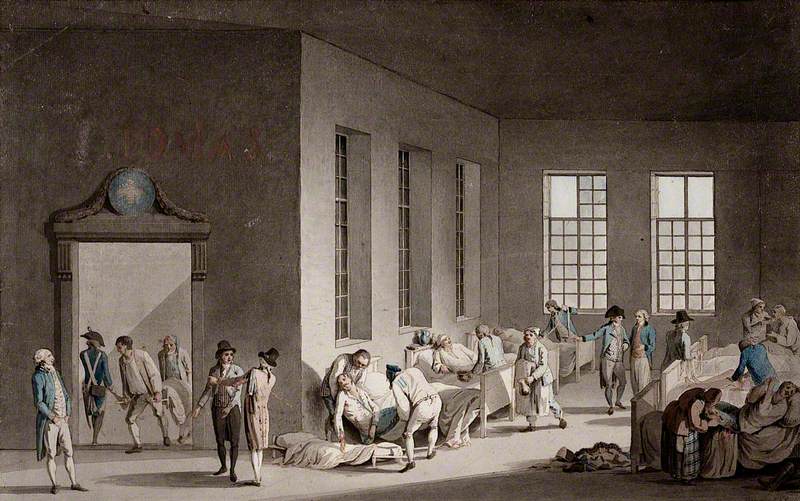

The Treatment of Wounded Soldiers in a Ward of a Hospital

c.1805–1811

Benjamin Zix (1772–1811)

Industrialization and urbanization in the nineteenth century led to more hospital than community care, but treatment could still vary greatly, with some hospitals depending on untrained orderlies or recovering patients to support others. Benjamin Zix's early nineteenth-century watercolour of wounded soldiers being treated in hospital shows all the chaotic activities happening in one space. Without consistent standards of medical care and practice, the time was ripe for change.

A vocation and a profession

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910)

1911–1915

Arthur George Walker (1861–1939) and Fiorini Foundry and T. H. Wyatt

It's impossible to tell the story of professional nursing in the UK without Florence Nightingale, whose work and fame following the Crimean War created sweeping changes in the education and perception of nurses. Following a religious and vocational call, Nightingale became a nurse over the objections of her wealthy family. In 1854, she was invited by the Minister of War, a family acquaintance, to bring a cohort of nurses to Turkey. There she organised the military hospitals and instituted new standards of hygiene that caused mortality rates to plummet.

Florence Nightingale as the Lady with the Lamp

J. Butterworth (active 1839–1854) (attributed to)

The popular image of Nightingale became the 'Lady with the Lamp', a motherly and angelic figure hovering benevolently over recovering soldiers in the wards. The romantic image first appeared in The Illustrated London News in 1855 and proliferated in lithographs, statues, and paintings.

The Mission of Mercy: Florence Nightingale receiving the Wounded at Scutari

1857

Jerry Barrett (1824–1906)

It filtered into other idealised depictions of nurses as well. By the end of the nineteenth century, the perception of nursing had changed entirely to one of standardised and respectable care, captured in the gentle camaraderie and respect of the 1892 painting Our Village Nurse.

Nightingale's popularity following the war is hard to overstate, though, of course, she was not the only nurse working to improve the profession. The main difference between Nightingale and Mary Seacole, who also felt compelled to offer aid in Crimea, was that of race- and class-based access.

While Nightingale was invited to improve nursing conditions in Turkey through family connections, Seacole spent her own money to set up the British Hotel, an independent nursing station and store. She treated soldiers on the battlefield, performed operations, and applied lessons learned from Afro-Caribbean medicine and a cholera epidemic she'd seen in Jamaica.

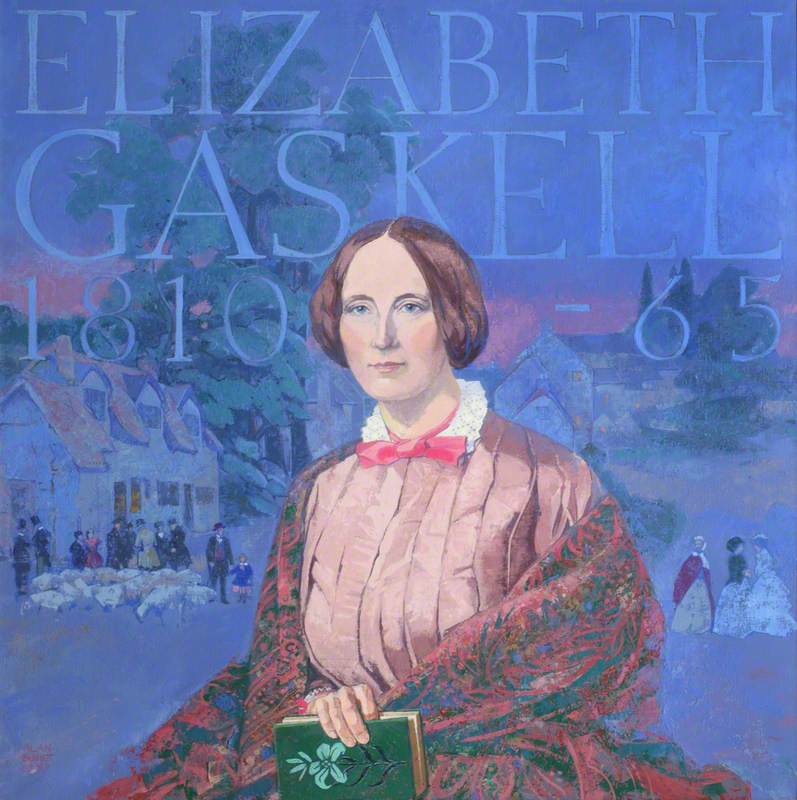

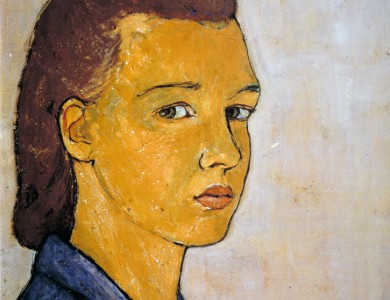

Mary Jane Seacole, née Grant

1869

Albert Charles Challen (1847–1881)

Seacole's 1869 portrait shows her stately with medals, but her contributions were largely overlooked until recently. Seacole was bankrupt after the war, while Nightingale was invited to work on nursing commissions, establishing a nursing school in 1860 and developing statistical charts and standards for the profession.

More recently, Seacole's image has been brought to the fore in efforts to correct the whiteness of the historical narrative; a 2016 sculpture shows her with a valiant forward stride. But it's important to understand the differences between Nightingale's and Seacole's depictions, and the reasons for them. Seacole's image is powerful now, but she had far less recognition the nineteenth century. For all the images made of Nightingale in her lifetime, the National Portrait Gallery's work by Albert Charles Challen (above) remains the only known portrait of Seacole from life.

In 2020, Greg Bunbury created a depiction of Seacole that uses Andy Warhol's screenprint style to comment on 'visibility, celebrity and western ideals of femininity'.

The images of these two iconic nurses embody ideas about gender and race that we're still unpacking today. Both Seacole and Nightingale contributed hugely to nursing's image as a profession that provided hygienic, scientific, and selfless care in horrific circumstances. This image would be called upon during both World Wars of the twentieth century, when heroic images of nurses were employed in campaigns to stir public sympathy.

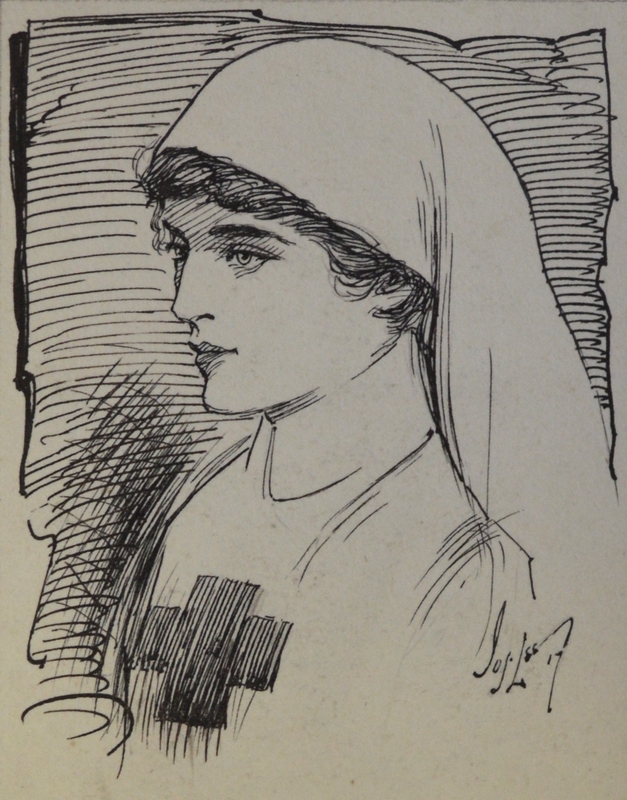

The execution of nurse Edith Cavell in the First World War shocked the public, and her sacrifice was commemorated in numerous works of art, often with an overtly patriotic message, like a painting of Cavell framed with flags and her death dramatised below.

First World War: The German Navy Attacking Allied Nursing

1918

Louis Raemaekers (1869–1956)

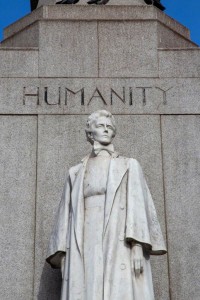

Similarly, a 1918 drawing of a German skeleton strangling a Red Cross nurse underwater was meant to condemn a torpedo attack on a hospital ship that killed 150 people, the cruel loss of life emphasised in the death of someone trying to preserve it. Cavell remains one of the few women (along with Nightingale and Seacole) with a statue in central London, its messages of 'humanity, devotion, sacrifice, and fortitude' underscoring the perceived role of a wartime nurse.

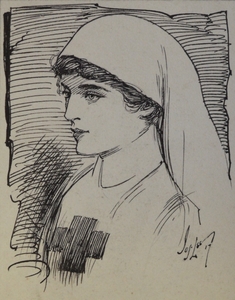

The Imperial War Museum's 1915 painting Nurse, Wounded Soldier, and Child centres a determined, straight-backed nurse who supports a soldier on a crutch with one arm and a huddled child with the other. These signs of strength and valour were a great change from images of sloppy nursing or Victorian depictions of women as a 'weaker' sex, but nursing imagery remained strongly tied to contemporary ideas of respectable femininity.

Wartime propaganda posters depicted nurses as winged angels or even 'the greatest mother in the world' to solicit support for the Red Cross. The Victorian 'angel of the house' became the angel of the battlefield.

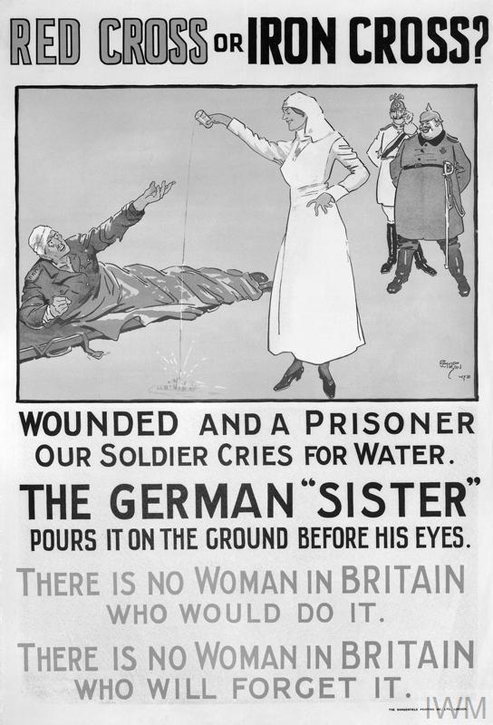

Red Cross or Iron Cross?

1914–1918, poster by David Wilson and WFB

Conversely, nurses on the opposing side were demonised as uncaring. This poster shows a German nurse pouring water on the ground rather than providing it to a wounded British soldier, with a direct appeal to women about their duties of care: 'There is no woman in Britain who would do it. There is no woman in Britain who will forget it.'

Medical Officer Attending the Wounded

1914–1918

Septimus Edwin Scott (1879–1962)

A plethora of depictions of nurses caring for soldiers on the battlefield – in calm, ordered wards, in transit, or in convalescent homes – captured the work and aftereffects of various conflicts and continued to promote nursing's reputation of selfless support.

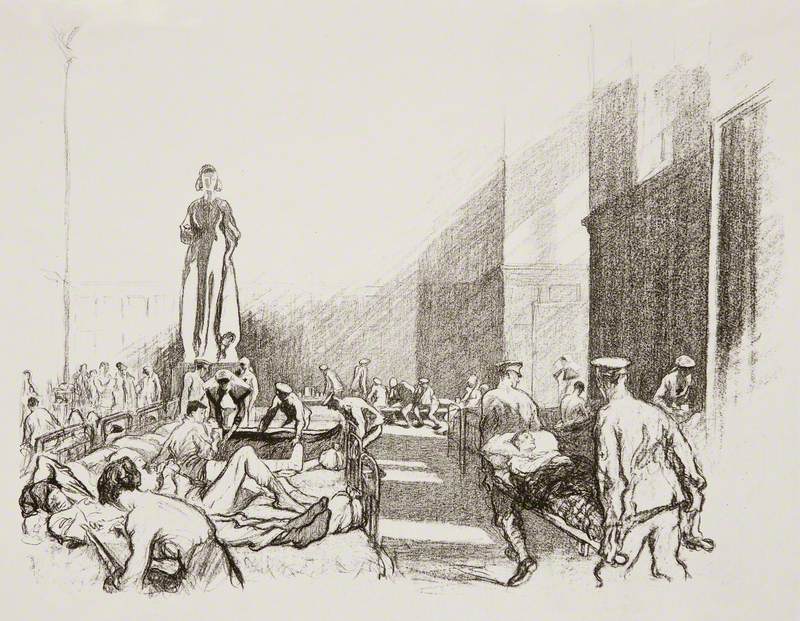

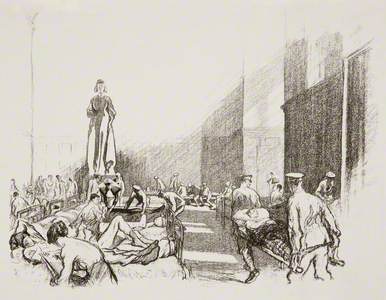

Many were done by war artists commissioned by the government to promote nationalistic ideals. A series of lithographs for the Ministry of Information in 1917 follows a wounded soldier from the front lines to convalescence, including a scene in hospital over which the shade (or statue) of Florence Nightingale stands guard.

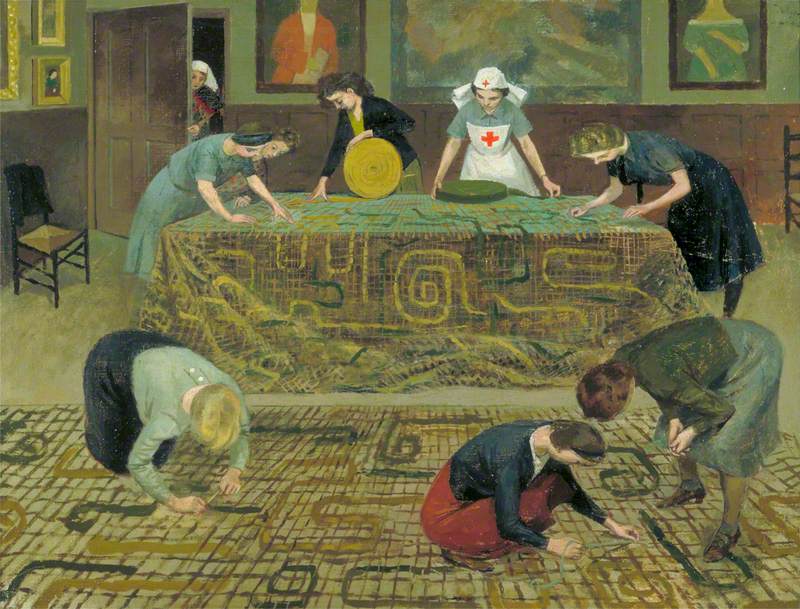

While war artists' depictions were usually dramatic and heroic, independent artists captured more relaxed scenes, like a nurse and a sister in Le Havre in 1919 or a 1941 scene of chatting nurses on a break.

A worn-out Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse, drawn in 1940, contrasts with those depicted in inspirational poses; a Second World War Ministry of Labour poster campaign encouraged nursing as 'a distinguished career for women.'

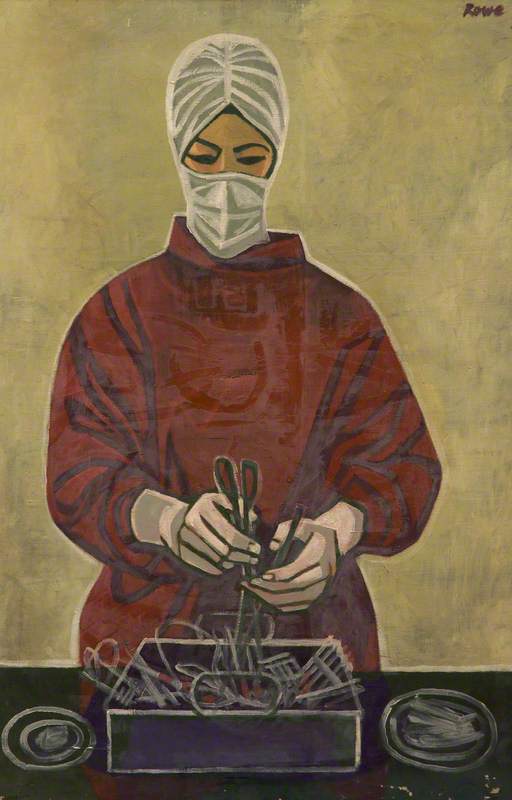

'Thoroughly Modern Nurses'

While wartime appeals still centred on a self-sacrificing ideal, the concept of nursing shifted over the twentieth century from a calling to a profession. Nurses were initially banned from marrying, but these restrictions began to lift from 1944. A push towards nationalised standards led to the Nurses Registration Act of 1919, which established a national register.

With the creation of the NHS in 1948, methods became even more standardised. When Eric Atkinson painted Street Scene with Nurse in 1955, district nurses who conducted in-home visits were a familiar sight. Nevertheless, heroic depictions of nursing had not entirely disappeared.

St John Ambulance Brigade Officer and Nurse

1955

Anna Katrina Zinkeisen (1901–1976)

As hospital training programs focused on women trainees, the gender imbalance in the profession continued. Male nurses recall sexist stereotyping in oral histories; only in 1951 were men fully allowed to join the professional register. In the 1970s, a leaflet advertising nursing to men showed a confident man in a suit, in contrast to earlier campaigns showing maternal and angelic women.

The language of nursing was also strongly gendered through the twentieth century, though titles like Ward Sister and Matron evolved towards the neutral Charge Nurse. Still, as of 2018, only 11% of nurses were men.

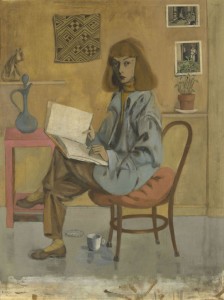

Over the twentieth century, portraits of (predominantly women) nurses ranged from vital young students to formal, imposing matrons and military leaders. While the elements of their uniforms varied, from caps to cornettes, they generally appeared starched, calm, and regimented. In each era, they reflected ideals of beauty as well.

Several turn-of-the-century watercolours in the Wellcome Collection, resembling fashion sketches, of an Army hospital nurse, district nurse, and hospital nurse in uniform flaunt the style and independence of the 'New Woman'.

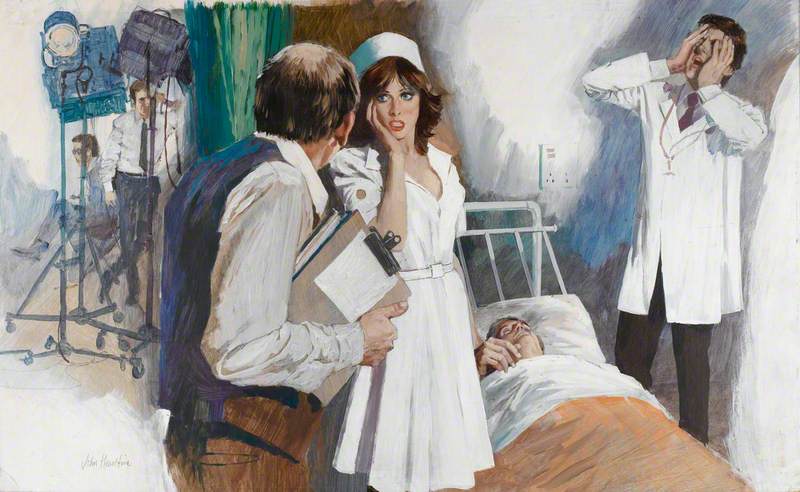

In other portrayals, nurses were overtly sexualised, like the nurse with a low-cut uniform and befuddled expression in this 1970s/1980s painting of a medical soap opera scene. Many popular postcards also made jokes about unwanted advances and the intimacy of their role. These themes are replicated in other mediums, too; one study found that 26% of film depictions of nurses between 1900 and 2007 portrayed nurses as sexual objects.

Like the profession itself, modern images of nursing continue to change. Many twentieth-century immigrants to the UK have served in essential nursing roles due to ever-growing needs for healthcare, and representation beyond the feminine, Anglo-Saxon ideal has slowly broadened.

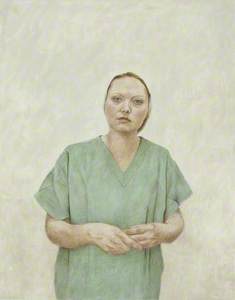

Depictions like Mark Moynihan's starkly human 2007 portraits of NHS nurses show people handling contemporary challenges and technologies. Images in the pandemic have also revealed nurses' burnout and exhaustion – reminders that they are human, not angels.

An automaton collection box in Guy's and St Thomas' Hospital provides an interesting reminder, too. Beneath the hospital motto 'It's better to give than to receive', a nurse whirls mechanically at three different speeds – all with a frozen smile – emphasising the varied and gargantuan demands we ask of those in the field.

Anne Wallentine, writer, editor and art historian

Further reading

Patricia D'Antonio (ed.), Routledge Handbook on the Global History of Nursing, Routledge, 2013

Gerard Fealy, Christine E. Hallet and Susanne Dietz (eds.), Histories of Nursing Practice, Manchester University Press, 2015

Claire Laurent, Rituals and Myths in Nursing: A Social History, Pen & Sword Books, 2019

Helen M. Sweet, Colonial Caring: A History of Colonial and Post-Colonial Nursing, Manchester University Press, 2015

Louise Wyatt, A History of Nursing, Amberley Publishing, 2019