Many of the sculptures in the exhibition 'Being Human' (at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery until spring 2021) show artists attempting to depict desired – and desiring – bodies. Too often the depictions centre on the female nude but is it business as usual or did these artists forge a new expression of desire?

'Pornography is another matter. Pornography attacks human identity; it is a destruction of individuality, an assault on the only thing we possess, and any artist concerned with making naked ladies must struggle to presume a balance between lust and compassion – the balance he wants to make the work right for him.' – Reg Butler

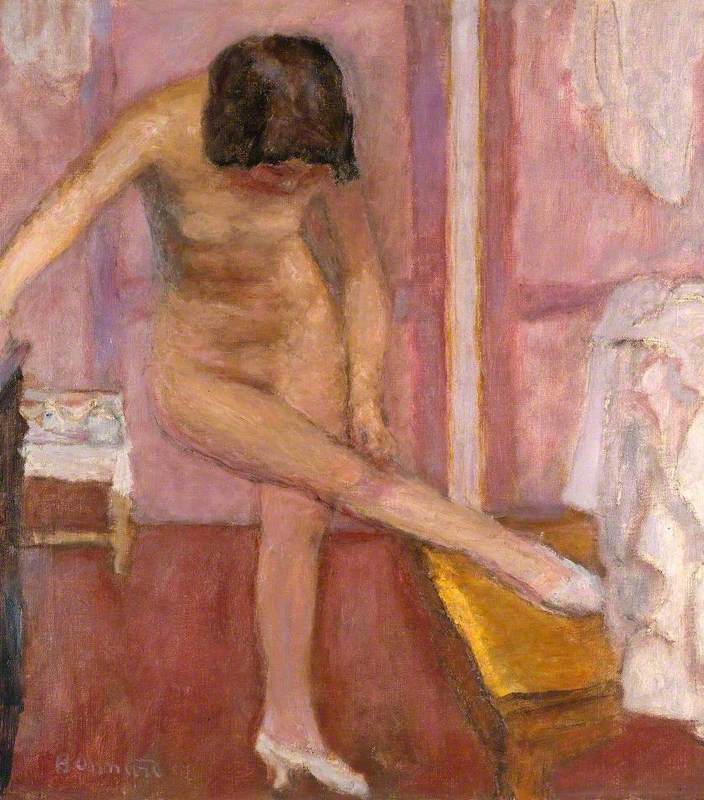

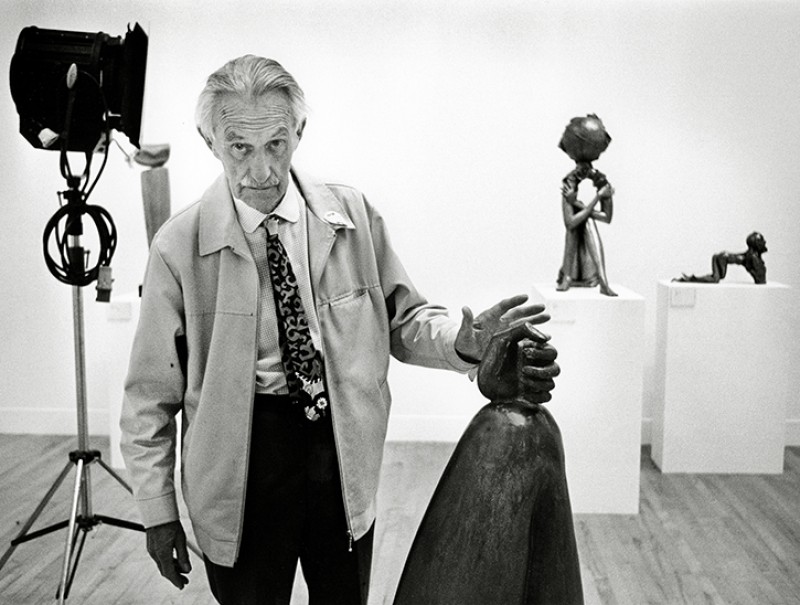

In the final lecture he gave before his death, Reg Butler discussed his lifelong obsession with representing the female form. It's a candid account by an artist attempting to expand his practice and to (re)create desirable, naked womanly bodies. Butler talks about the 'hairy, sweaty, grainy flesh' of Pierre Bonnard's painted nudes in a way that sounds objectifying, and it is: Butler was focusing unflinchingly on the sheer physicality of his subjects.

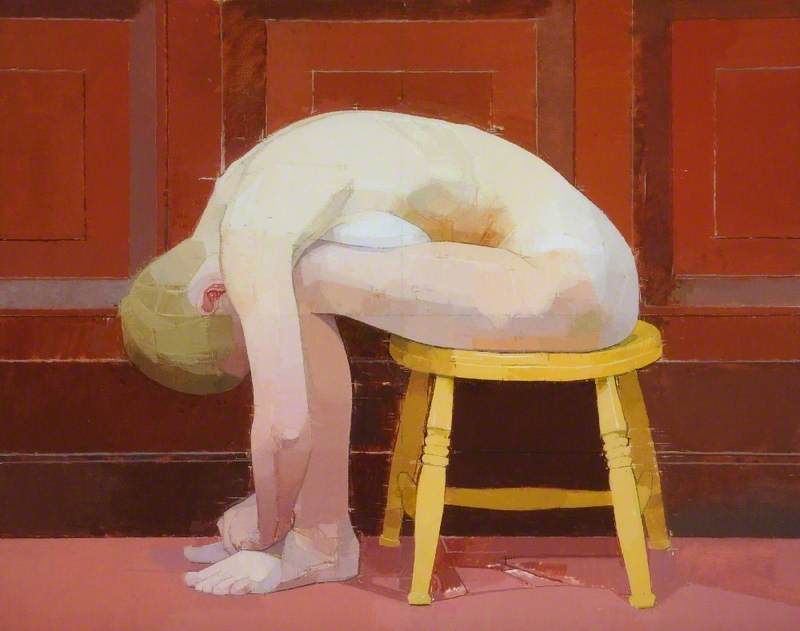

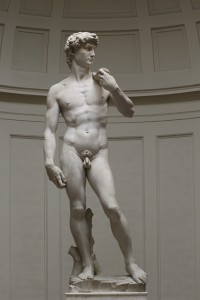

While teaching at the Slade School of Art, Butler anticipated Kenneth Clark's distinction between the nude and the naked: that is, between a contained and idealised feminine beauty and the living, organic, naked body. This desire to portray the real, unidealised body connects with those titans of modern sculpture, Rodin and Jacob Epstein, as does the sexualising intention: are Butler's 'naked ladies' liberated, desiring bodies or sexually objectified figures?

A feminist appraisal of Butler's sculptures can tell us a lot about the post-war male gaze. The eroticised contortions of his late sculptures are undeniably disturbing.

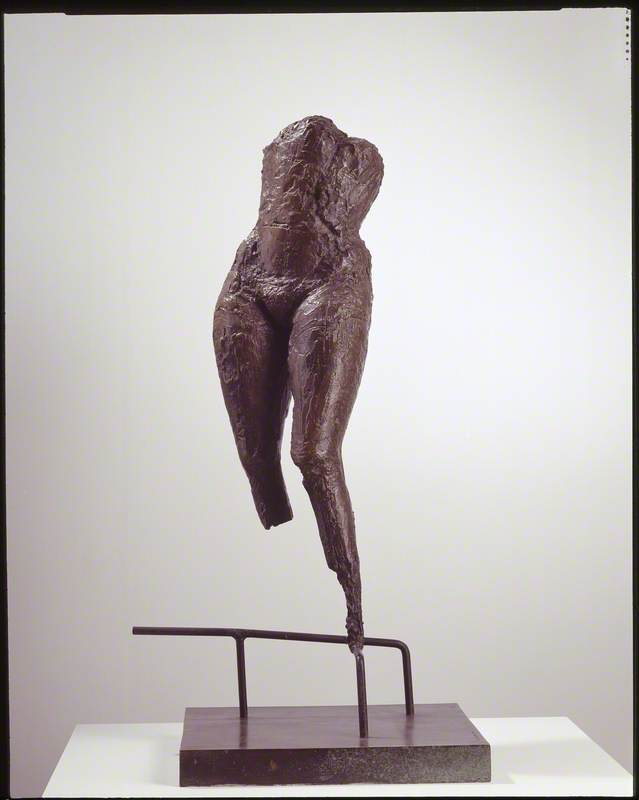

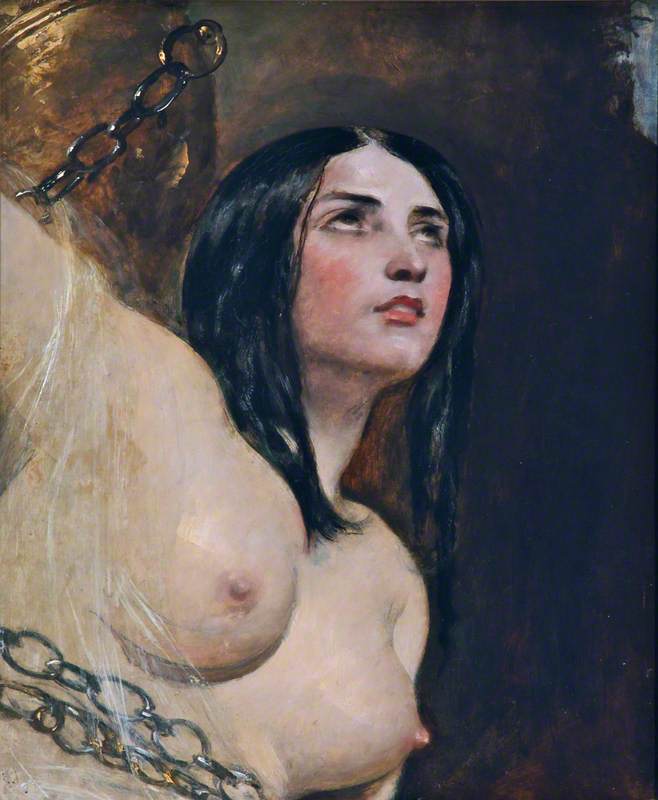

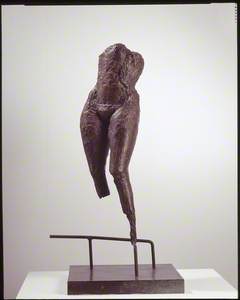

Such contortions are hinted at in his long-limbed Girl, who balances half-naked on a bar and pulls a clinging garment over her head, revealing the underside of her breasts. Her genitals are explicitly rendered. Is she really a 'girl' or a young woman? The lazily stretching figure combines vulnerability and defiance. Looking upwards, her face turns away from ours, spurning our gaze.

Girl

1953–1954, bronze by Reg Butler (1913–1981)

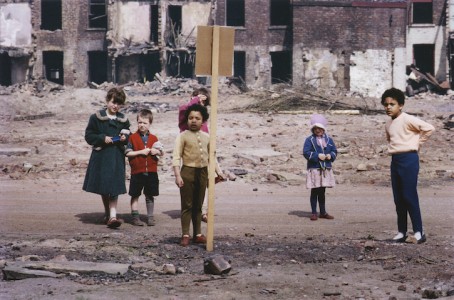

Today's audiences may find the adolescent appearance of the Girl shocking. But perhaps her provocative undressing and nakedness can be seen as an indicator of agency that the idealised female nude sculpted and painted by male artists rarely achieved in art. The 1950s saw something like a social lockdown. After the relative freedoms of war work, women found themselves back in the kitchen, idealised as domestic goddesses and care-givers.

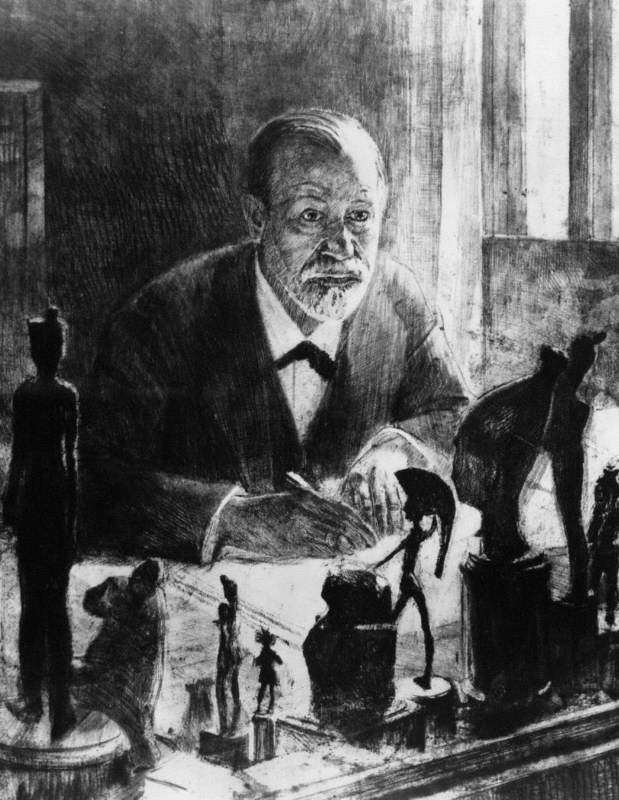

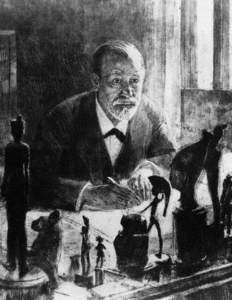

At the same time, Freud's unsettling articulation of the unconscious and of repressed sexual desire had become common currency. In this context – the theory of unconscious desires repressed during childhood as part of socialisation – could be read as a metaphor for the conformity of post-war society.

Butler was open about the way that sexual desire informed his depiction of the female nude. He used ancient and global sculptural forms to explore and express psychoanalytic theories on human sexuality.

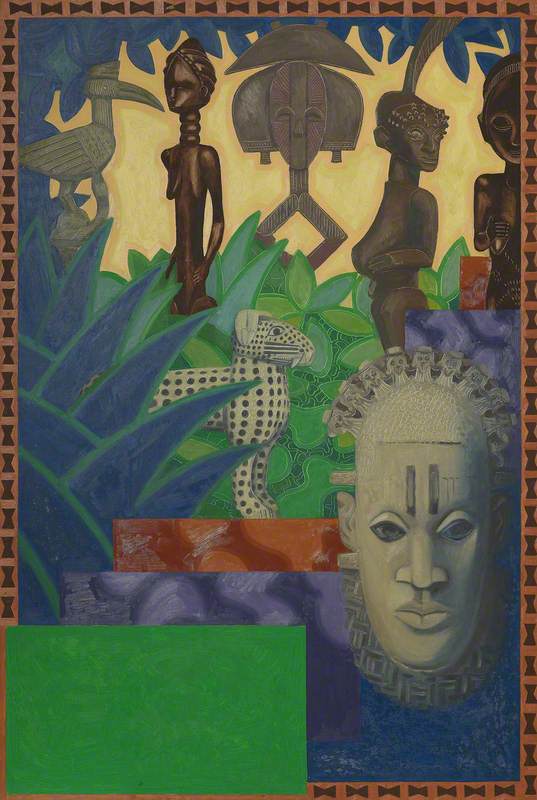

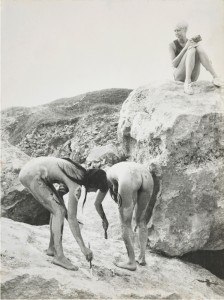

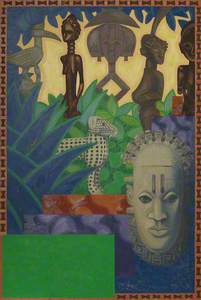

Anthropology offered western culture a conduit to repressed desires through the ritual objects of Africa, the Far East and the Pacific. Increasingly these were interpreted and collected as art objects, a process of appropriation which we problematise today. The interest in these artefacts freed European artists in the twentieth century from Picasso and Jacob Epstein onwards, to create radically naked forms, imbuing into their work the potent sexuality they found in these objects.

Today we would also ask questions about exoticism and appropriation. That is even before we consider how such objects happened to be in our museums and private collections at all.

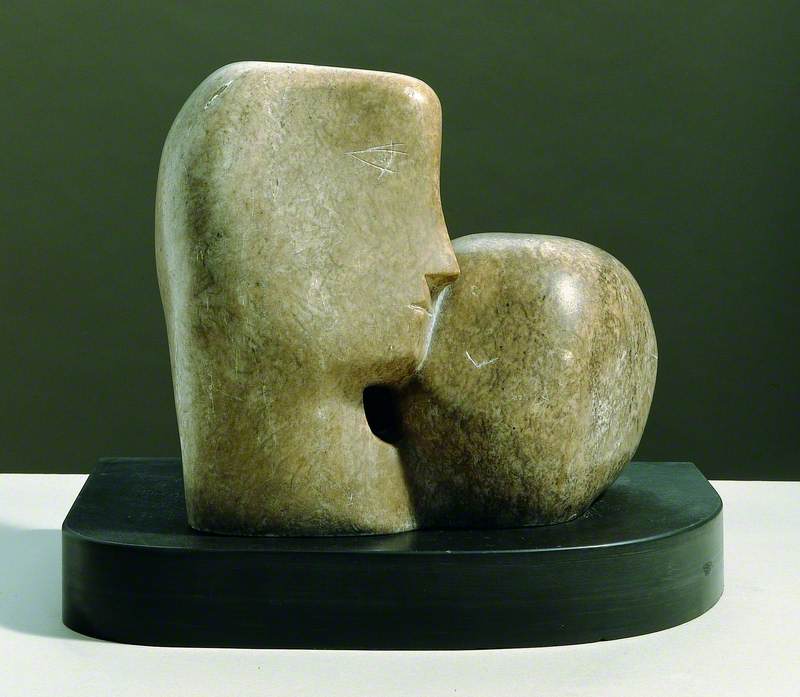

Butler found inspiration from world cultures as can be seen in his Circe Head and Musée Imaginaire, but it was ancient carvings that had an enduring influence. During his lecture, he passed around a model he had made based on the Venus of Lespugue, a bulbous female form very close to the Willendorf Venus.

The frank nakedness of Girl rejects the sanitised art historical tradition of the female nude and returns to the bodily realism of the ancient Venus. It's possible that the sexuality of Girl has an erotic agency that frees her from being an abstract ideal.

'The sensation of any of those figures is of a structure on which the flesh hangs, like a bag of water... and there is always in them a sense of gravity... which is an important part of being upright, or indeed, of being human at all' – Hubert Dalwood

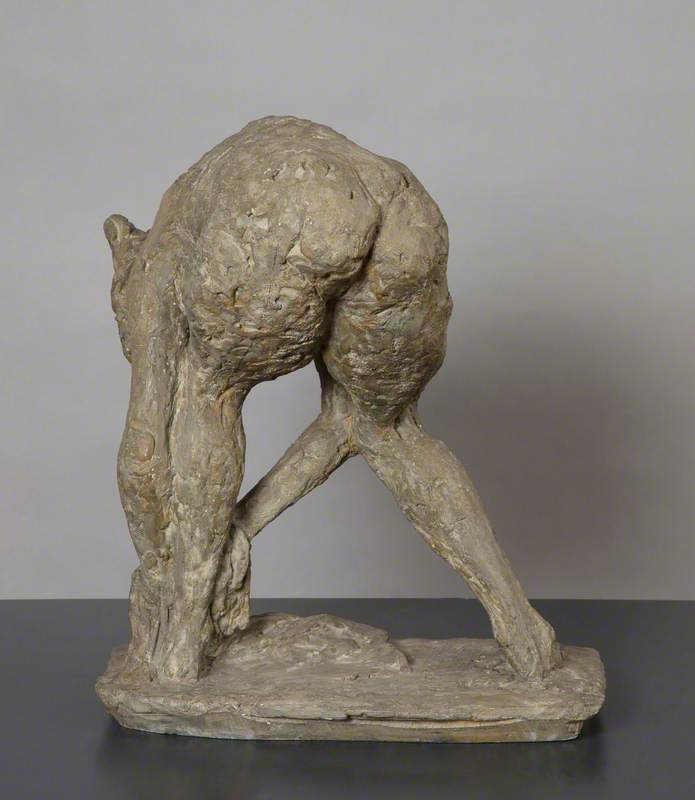

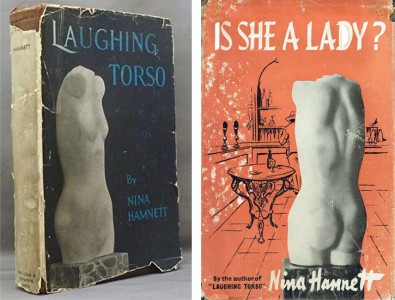

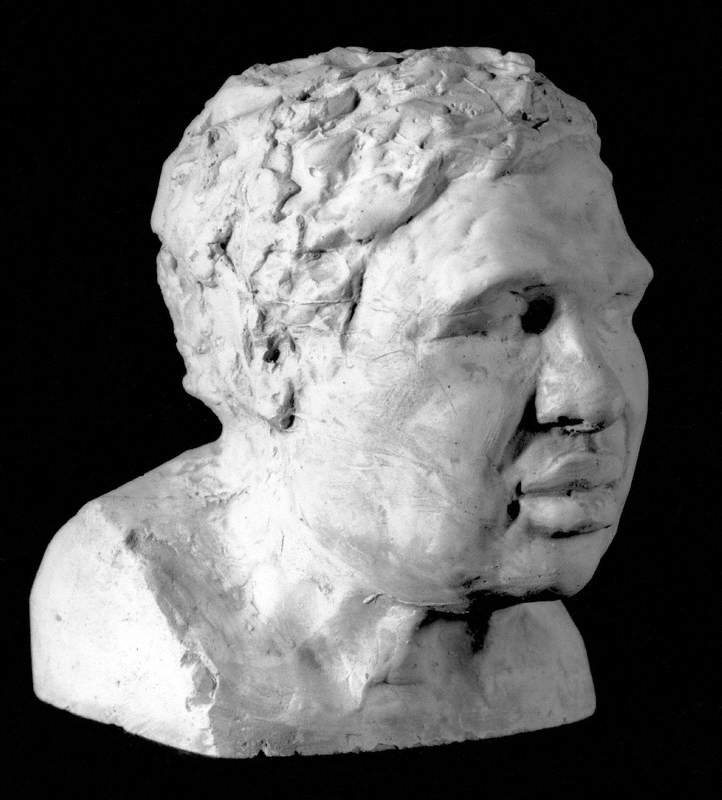

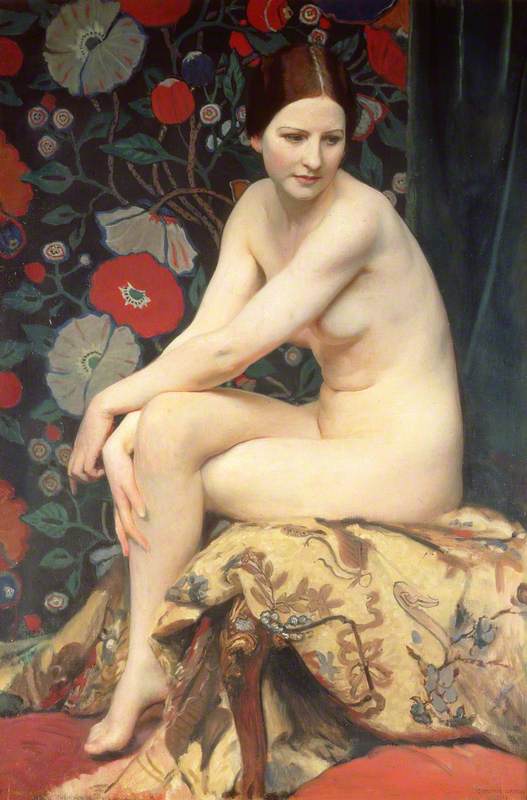

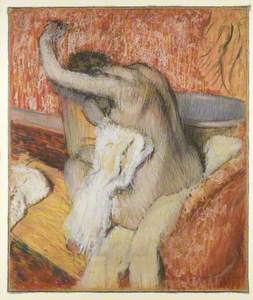

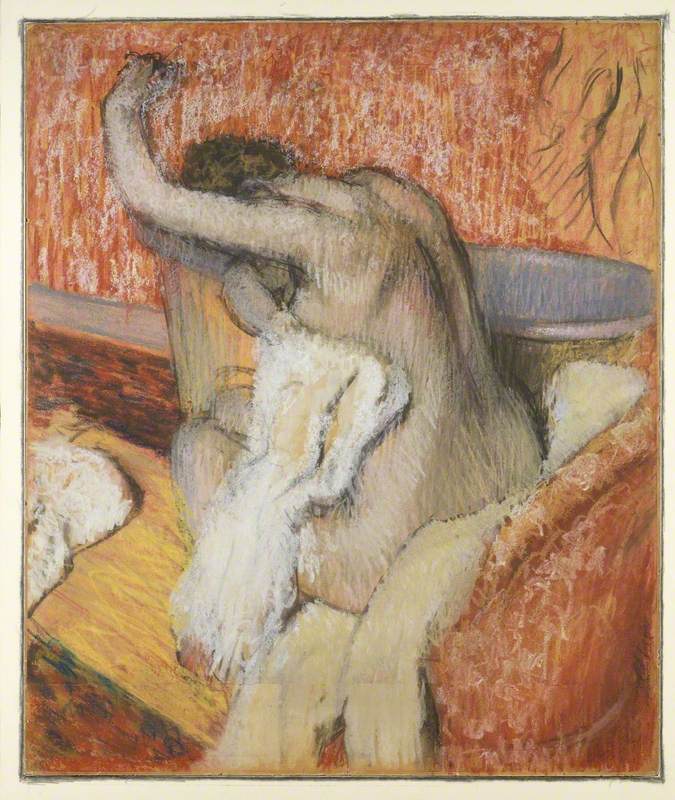

Hubert Dalwood's Woman Drying Her Feet desexualises his subject. The sculpture depicts an intimate moment, reminiscent of Degas's bathers but seen through the framework of 1950s social realism, or indeed Butler's 'nakedness'.

After the Bath – Woman Drying Herself

c.1895

Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

Dalwood described this early suite of female figures as 'squat figures sitting on lavatories' in a deliberate flouting of standard exaltations of the female nude. (Perhaps a brutal Anglophone variation of the toilette?)

The resemblance of his sculptures to ancient Venuses shows how Dalwood used these forms to give expression to a more primal reality. His portrayals of women, while not unproblematic, show naked rather than nude figures.

The depiction of a woman washing, which is such a staple of art history, is defamiliarised by Dalwood's matter-of-fact treatment which reminds us that actually we are glimpsing a private moment. Our implicit voyeurism is underlined by the very tactile quality of Dalwood's roughly rendered plaster figures as if we trace these lumpen bodies with our objectifying glance.

It is illuminating to compare these artists to their female contemporaries.

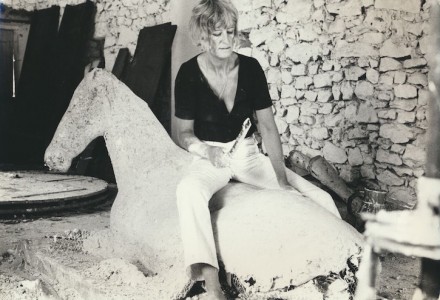

When interviewed about her own sculpture practice, Rosemary Young (who became Reg Butler's studio assistant and wife) said that in the 1950s: '[to become a successful female artist] you had to be a very very extraordinary person.'

What makes this statement all the more revealing is that Young was describing Butler's attitude to his female students. Moreover, in the same interview, Young revealed that she had most likely made the shell cast Girl in her role as Butler's assistant. What's remarkable is that Young doesn't sound resentful; she seemed to see her role supporting Butler as very much a partnership – and an adventure. But she was clear that this role was all-consuming and that she was unable to make her own work, only returning to it later in life after Butler had died.

The undated Girl Drying Her Foot shares Dalwood's subject, but has an elegant angularity.

Sculpture seemed to concentrate the machismo of the would-be blue-collar, bedsit-dwelling Jimmy Porter types of the 1950s, with its heavy lifting, casting molten metal, welding, smithing, shifting great blocks of material around the studio.

'I didn't think of myself as a "woman sculptor".' – Elisabeth Frink

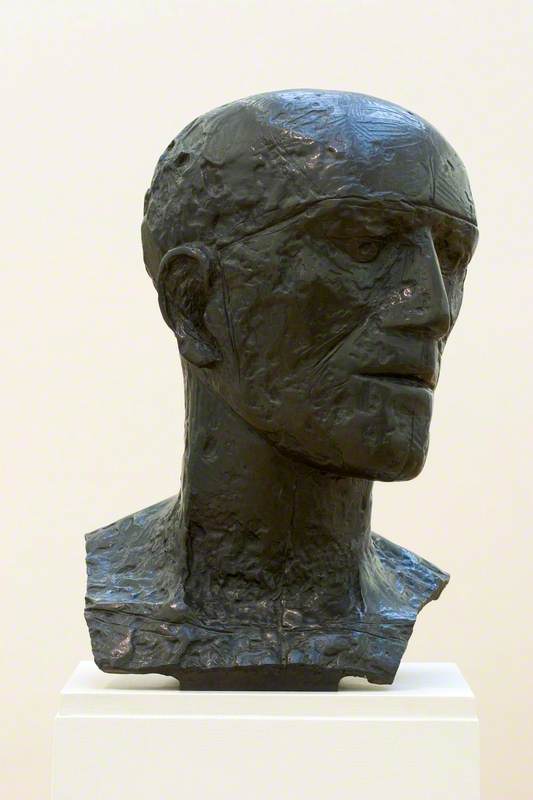

Elisabeth Frink was defiantly open about her attraction to virile, active men. Can we read this as a response to the male-dominated nature of her chosen field?

It is notable that she repeatedly represented the violence inherent in this model of masculinity, such as her thuggish soldiers and the Goggle Heads, as well as its victims, in her Tribute Heads.

In this context, Frink's remarkable career is testament to her determination and talent. But like many women of her generation, she avoided tackling the subject, saying, 'in the arts you can't differentiate between the sexes: men and women are equal.'

Unusually for a sculptor, Frink worked without an assistant. Conceivably it was because of the male bias of sculpture, with its many examples of female nudes, that she produced work that took the male body primarily as its subject (Frink hardly ever made images of women). In the 1980s she was invited by Pat Whiteread (the mother of Rachel Whiteread) to participate in the ICA show 'Women's Images of Men'.

If Butler felt free to create an object of desire then so could Frink: 'I enjoy looking at the male body, this has always given me the impetus and the energy for a purely sensuous approach to sculptural form. I like to watch men walking and swimming and running and being.'

This can be read as an inversion of the masculine tradition of the female muse. It could also be seen as following in the footsteps of Epstein and Gaudier-Brzeska who set a standard for dynamism and vigour in sculpture. Frink's subjects were masculinity, virility, the outdoors, nature, animals and death.

'I think that's very much part of human beings – vulnerability and strength – the mixture of both that I find in the male figure is very important to me as an idea.'

If the naked female figures of Butler and Dalwood and their peers represent, alternately, male desire or horror, distorted by the repression of the post-war era, then the work of Frink can be seen as a response to this ambivalence, and it is only now that we are becoming acquainted with Young's.

Feminist and queer art history and art practice have revealed that desire is polymorphous and not only played out over the female body, indeed that beauty exists beyond the binary. But in its daring and frank eroticism we can reappraise the contribution made by Butler and Frink's generation.

Julia Carver, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery

The exhibition 'Being Human' is at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery until spring 2021

Further reading

Alan Bowness, Lynn Chadwick, Methuen, 1962

Alan Bowness and Penelope Curtis, Bernard Meadows: Sculpture and Drawings, Henry Moore Foundation, Lund Humphreys, 1995

Richard Calvocoressi et al., Reg Butler, Tate, 1983

Andrew Causey, Sculpture since 1945, Oxford History of Art, 1998

Penelope Curtis, Sculpture 1900–1945, Oxford History of Art, 1999

Ann Elliott (ed.), Kenneth Armitage, Sculptor: A Centenary Celebration, Samson & Company, 2016

Albert E. Elsen, Pioneers of Modern Sculpture, Hayward Gallery, Arts Council, 1973

Dennis Farr, Lynn Chadwick, Tate retrospective, 2004

Margaret Garlake, Reg Butler, Henry Moore Foundation, 2006

Sandy Nairne and Nicholas Serota (eds.), British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1981

Herbert Read, Modern Sculpture: A Concise History, Thames and Hudson, 1964, reprinted 2001

Calvin Winner (ed.), Elisabeth Frink: Humans and Other Animals, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, 2018

Rosemary Young interviewed by Gillian Whiteley, National Sound Archive, Artists' Lives, British Library, 1999–2000