Ever since Art UK began photographing every publicly owned oil painting in Britain, I’ve been keeping a careful eye out for potential discoveries lurking in the forgotten corners of our national collection. The fact that over 80% of Britain’s public collection is in storage at any one time never ceases to amaze me. But statistically this suggests there must be scores of lost masterpieces waiting to be found.

When the BBC commissioned Jacky Klein and I to make a new series, 'Britain’s Lost Masterpieces', we knew that in the Art UK website we had the perfect tool with which to begin our voyage of discovery. And fortunately, hundreds of hours searching through Art UK have thrown up some intriguing mysteries.

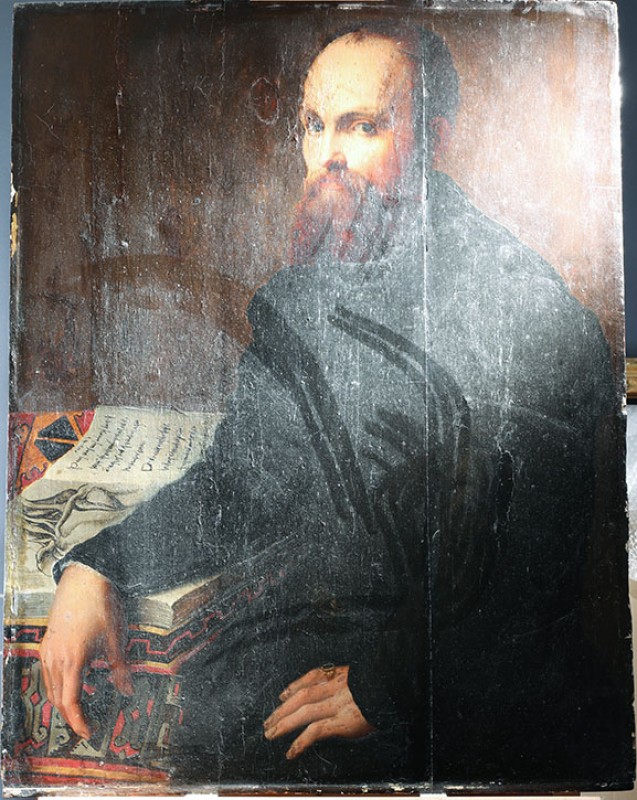

The first programme in the series examines a painting that we discovered in Swansea Museum, via Art UK. It was catalogued as a work by an unknown artist, but has now been proved to be a rare and highly important preparatory study by Jacob Jordaens. The subject is the Greek classical myth of Meleager and Atalanta, which Jordaens explored a number of times throughout his career.

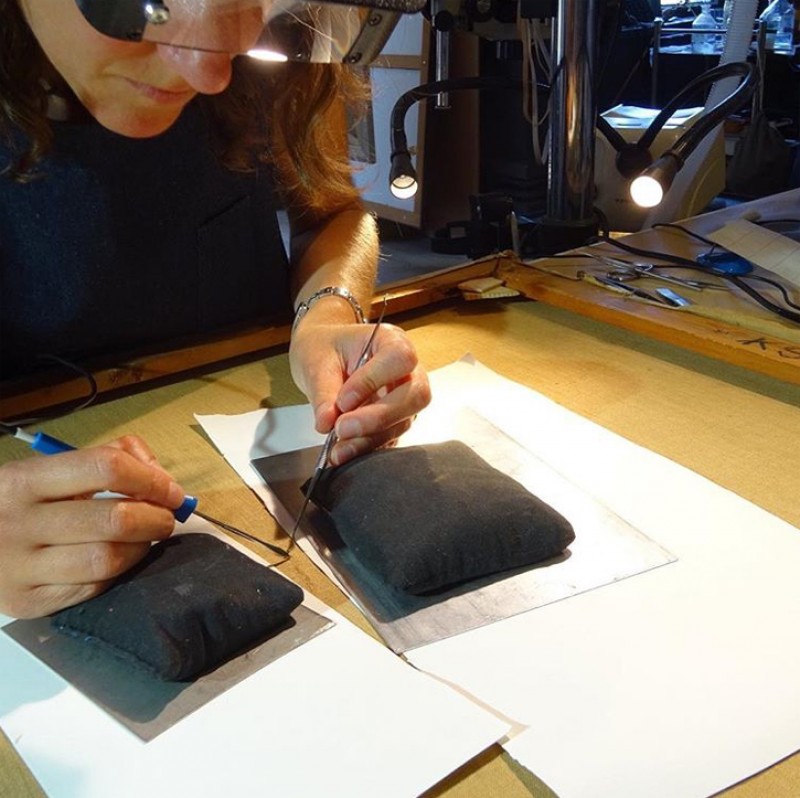

Finding the picture was, in this case, only the beginning of the story. The painting had been comprehensively over-painted by a previous restorer, probably in the 1960s or 1970s. This ‘restoration’ – some of the worse I have ever seen – obscured large swathes of original paint, and in order to prove the attribution to Jordaens we would have to remove it. But it was far from clear when we first examined the painting that this would be possible. In most cases, overpaint, even if badly applied, is there to cover up damage to the original painting.

But we were lucky. After initial analysis with our series restorer, Simon Gillespie, we could see that the Swansea painting had been overpainted largely for cosmetic reasons. The original light blue, overcast sky had been turned into the sort of sky you’d find in a Club Med brochure; the horses’ manes had been trimmed in garish pink; and Atalanta’s white dress had been made red. Happily, Simon was able to safely remove the overpaint, revealing a painting made in Jordaens’ characteristic technique, with numerous ‘pentimenti’, or alterations, showing how the artist evolved his creative ideas.

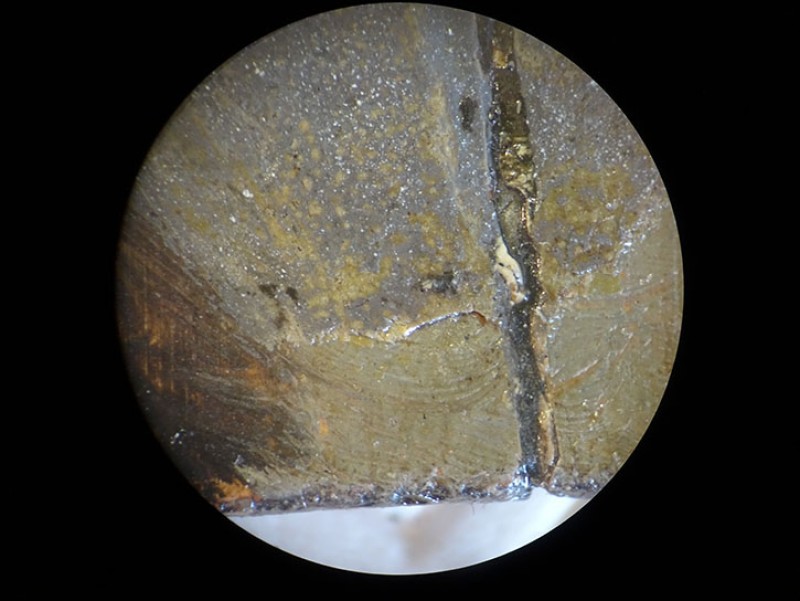

A far harder challenge came in the form of received wisdom on Jordaens’ working technique. According to many art historians, the finished picture for which we believed the painting in the Swansea Museum was a study, a large depiction of Meleager and Atalanta in the Prado Museum in Madrid, was painted in two stages, some 20 years apart. The right-hand section showing Atalanta and Meleager was thought to have been painted in 1620, and the left, with additional figures and horseman, in about 1640. A prominent seam down the centre of the Prado painting appeared to prove the theory. And because the painting from Swansea showed elements found in both sides of the Prado picture, it must, according to Jordaens’ scholarship, be a copy painted after the Prado painting was completed.

We therefore had to prove that the painting in the Prado was painted all at once, and not over two decades. Indeed, we had to counter the idea that Jordaens was an habitual ‘adder on’ of bits of canvas, and the suggestion that he did not think deeply about his compositions, but rather bodged them together in an ad hoc manner over decades.

Fortunately, after detailed analysis of much of Jordaens’ oeuvre, as well as a study of the materials available to him at the time, we were able to demonstrate that the Prado picture was indeed conceived and constructed as a single composition. The seam can be explained by the fact that Jordaens was buying canvas in 120 cm wide sections, a standard width available at the time, and simply joining them together when he wanted to make a larger composition. A number of Jordaens paintings from early in his career are, like the Prado picture, 240 cm wide, and show a similar seam down the centre. Furthermore, we found a series of panel makers marks on the back of the wooden panel on which Swansea study was painted, which proved that it had to date from between 1619 and 1621. Final confirmation came when we were able to show the painting to the director of the Rubenshuis museum in Antwerp, Ben van Beneden.

Many might be surprised that such discoveries could still be made in British museums. But thanks to Art UK we can now, for the first time, undertake a truly complete survey of the UK’s national art collection. And the best news is that this work can be undertaken by all manner of expert eyes, both professional and amateur. I later discovered that a number of other Art UK users had already connected the painting in Swansea to Jordaens, including Prof. David Ekserdjian, the eminent art historian, Al Brown, a sharp-eyed regular on the Art Detective website, and Francis Mouton, a sleuthing blogger from Belgium. In other words, anyone can have a go – so why not start your own search today?

Bendor Grosvenor, art historian and presenter of BBC Four's Britain's Lost Masterpieces