I am an artist based in Glasgow, and my current PhD research at Glasgow School of Art looks at the precarity of working-class places in the north of the city through the displacement or dilapidation of sculpture in community space and social housing schemes.

Sculpture provides us with a powerful route to understanding the way social housing and civic amenities are reconfigured in post-industrial cycles of regeneration.

One of the first objects I looked at early in my research was Henry Moore's Draped Seated Woman, a public sculpture originally sited on the Stifford Housing Estate in Stepney, East London. The work had been acquired from the artist by London County Council, and its story provides a good example of what I am looking at now in Glasgow.

Henry Moore, a lifelong socialist, generously sold Draped Seated Woman to the council at cost price, and it was installed in 1962, the year after the estate was completed. It featured in Joan Littlewood's 1963 kitchen-sink drama Sparrows Can't Sing, starring a young Barbara Windsor. The film was set during the slum clearances in London's East End, and the impact of displacement is at the heart of the story.

Barbara Windsor with 'Old Flo' on the Stifford estate

Stifford's three 17-story towers were demolished in 1999–2000, and the fact that Moore's sculpture outlived them is crucial to my research. Nicknamed 'Old Flo' by locals, Draped Seated Woman was initially moved to Yorkshire Sculpture Park, and then in 2017 was relocated to Cabot Square in Canary Wharf, where it was photographed for Art UK.

There was significant controversy around this placement. Tower Hamlets Council attempted to auction off the work, in a move that was largely condemned. Eventually, Old Flo was taken back to the East End but was completely recontextualised through its placement at the centre of a financial district.

My work focuses on Springburn in the north of Glasgow – the place where I am from. Delving into Art UK has enabled me to expand my research thinking on this place enormously, because it has allowed me to cross-reference art in one area through a period of time.

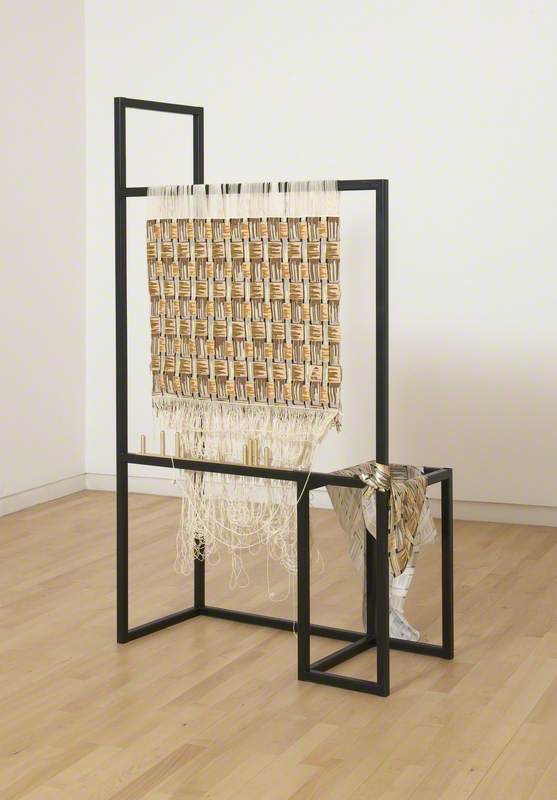

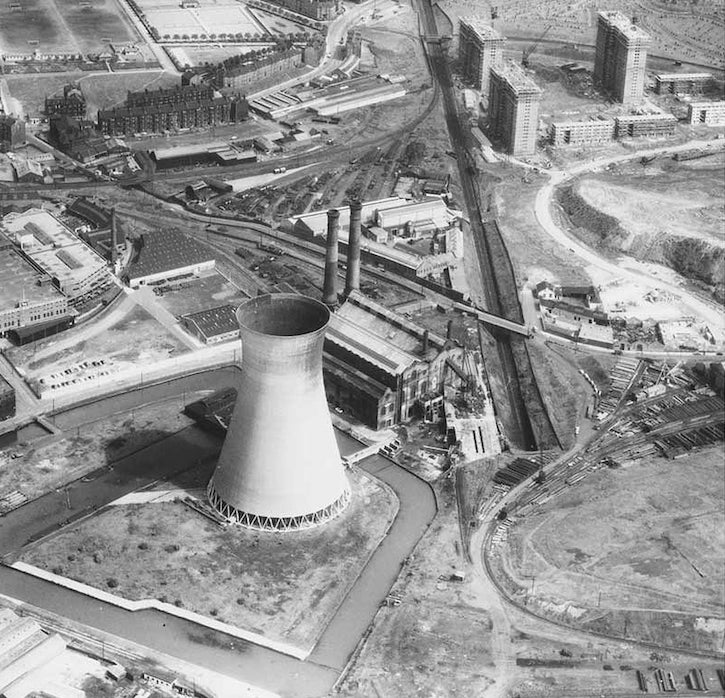

Aerial view of Sighthill, Glasgow, in the 1960s

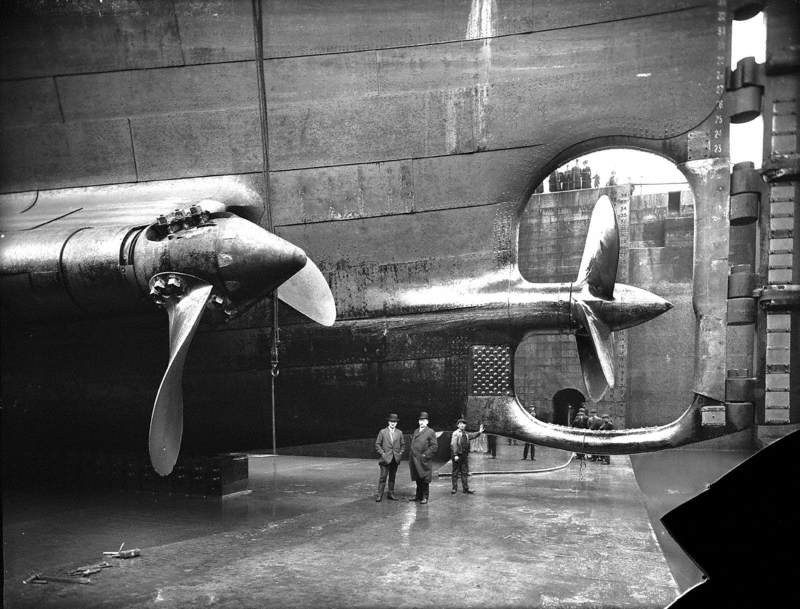

In this image from the late 1960s, we can see high flats being built. We are looking at the construction of Sighthill, a former scheme within the wider area of Springburn, which has an immense industrial history in the fabrication of locomotives and the repair of diesel trains.

The key things from this photograph that remain today are the train tracks and the cemetery. The power station and cooling tower, the darker tenements – hundreds of potential council homes – have all been demolished. However, here too a sculpture that was installed as an amenity for the housing scheme has outlived the scheme itself.

Sighthill Stone Circle

The Sighthill Standing Stones were the first sculptural objects I saw that were intrinsically directed at me and people like me. Sighthill was punctuated by these immense tower blocks – built in the late 1960s and demolished between 2009 and 2016. My extended family were among the first tenants, but unlike the 'New Town' of Glenrothes in Fife, where my other cousins lived among concrete hippos and mushrooms, there was no public art in Sighthill.

Hippo Group in Glenrothes

1973, outdoor sculpture in Glenrothes by David Harding (b.1937) and Stanley Bonnar (b.1948)

Later, I came to understand that these colossal blocks were a form of art in themselves. I perceived them as great minimalist slabs – enormous artefacts I could enter, or landmarks on the skyline I could use to locate myself at a distance.

In the late 1970s, when the Sighthill Standing Stones arrived, it was a big deal. At the time, the local area known as 'The Cuddies', a former industrial chemical dump, was being regenerated as a place for people to walk or exercise, and the stones were placed in this landscape.

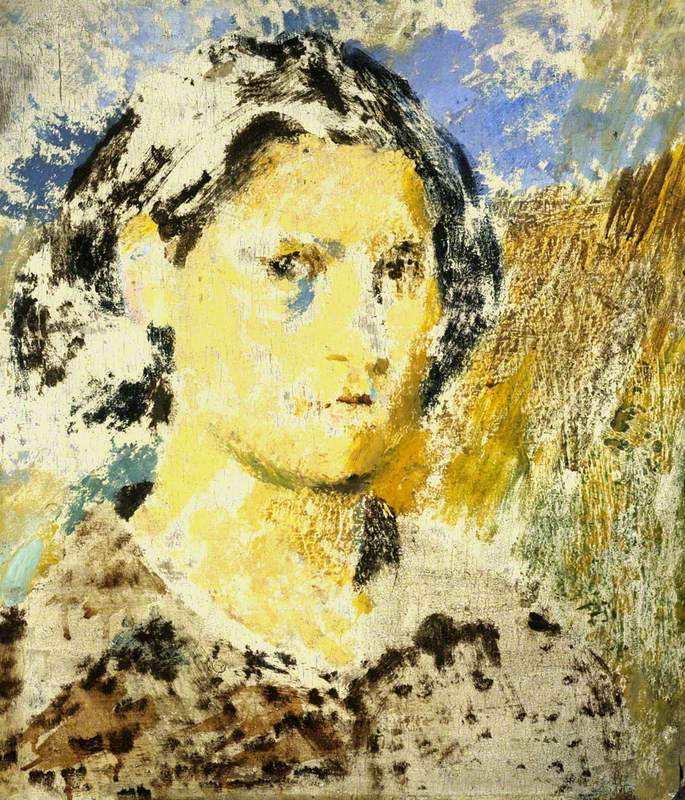

This etching by Muirhead Bone illustrates this landscape before any housing was built there – never mind a stone circle.

St Rollox

(from the series ‘Glasgow: Fifty Drawings by Muirhead Bone’) 1911

Muirhead Bone (1876–1953)

It was a cold, dreich day when the stones arrived, with frozen slush on the ground. There was a grimness about it: raw sky above the place known as 'The Stinky Ocean', where the sulphurous reek of the former chemical dump signalled contamination.

The idea for the 17 stones came from the writer Duncan Lunan. He designed the first astronomically aligned stone circle in 3,500 years to be erected in the UK.

These were the sun stones. The corresponding moon stones were never installed because Margaret Thatcher defunded this and similar projects throughout the UK. Instead, the moon stones languished on the side of the hill.

I remember seeing them installed, watching the Royal Navy Sea King helicopter lift them, one at a time, into the mud. I was at school, and could see the chopper from the back window. It was hoisting a slanting corpse of stone, dangling from chains. Each cadaver was torn from the quarry, blasted with slow, deep care.

A Sighthill stone arriving by helicopter

A higher frequency blast would have shattered the stone and resulted in smaller objects. But these were mollycoddled, birthed large, and erected ready to tell the time. The chemical dump was improved by this cosmic clock, but the circle was always upstaged by those other, bigger standing stones – the flats, looming in their own unaligned formation.

The proposed removal of the Sighthill Standing Stones in 2013 was one of the first indicators that the green space between Sighthill and Glasgow city centre was under threat from developers. The last time I visited, around 2015, I had startled a deer that was sunning itself in the long grass nearby.

There was also a significant bat colony, and residents campaigned to keep the space wild. Duncan Lunan started a protest to save the stones. They were saved, but were migrated and placed very close to some of 1,000 new housing units, only 198 of which will be for social rent.

Having experienced the demolition of the flats and moving of the stones as a kind of grief, I found this to be a recognised aspect of working-class experience, described by Marc Fried in Grieving for a Lost Home and Richard Sennet in The Hidden Injuries of Class. If there is any solace, it is in the constancy of the dead. Sighthill Cemetery was a playground to us. It's now an official public greenspace.

Sighthill Cemetery

(from the series ‘Glasgow: Fifty Drawings by Muirhead Bone’) 1911

Muirhead Bone (1876–1953)

This etching, also by Muirhead Bone, depicts Sighthill Cemetery as it was more than a century ago. What I am amazed at here is the sense of emptiness and how that chimes with the current state of Sighthill as a flattened site awaiting regeneration.

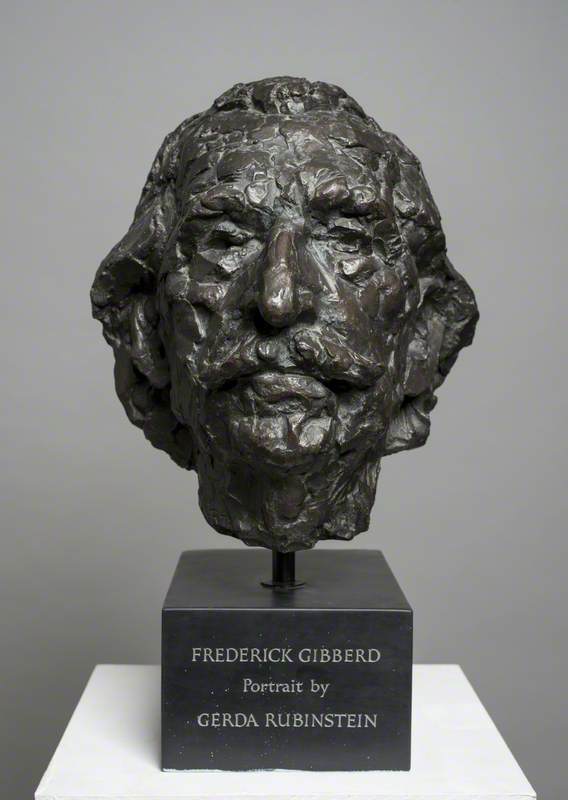

Three eminent Scottish sculptural stonemasons are buried in this cemetery – William Mossman (1793–1851) and his two sons, William Mossman Junior (1824–1884) and John Mossman (1817–1890). Their work proliferates in Glasgow, adorning the City Chambers and the Mitchell Library. Their sculptures are most present amid the grandeur of the city centre, but their own resting place is among the remnants of heavy industry.

The locomotive industry in Springburn was globally significant – at one point the ward was supplying one-fifth of the world's trains – and this is reflected in the sculpture that can (or could) be found in the ward. Sandstone sculptures representing Science and Speed, flanking a locomotive, emerge from the facade of the former offices of the North British Locomotive Company in Springburn like an early Lumière brothers' film.

Allegorical Figures of Speed and Science

1909

Albert Hemstock Hodge (1875–1917) and James Miller (1860–1947) and P. and W. Anderson Ltd

Another work from 1987 – The Straw Locomotive by George Wyllie – provides both a reminder of this industry and a post-industrial eulogy. In the image below, we can see the tower blocks at Wellfield street in Springburn as the artist sits triumphant on his train, which he had driven through the streets of Glasgow before suspending it from the Finnieston Crane and setting it alight, marking the death of the city's heavy industry.

In 2019, amid significant protest, the 163-year-old St Rollox railway works were closed to workers, marking the end of the locomotive industry in North Glasgow. Decades before this final closure, the ward's remarkable legacy of grand, late-Victorian philanthropy had already fallen into decline – including a Carnegie library, public halls, and a park with glazed winter gardens.

Now, in a little pocket of communal seating in the ward nestles The Works – a little-known work by Sibylle von Halem. Commissioned as part of a Milestones project initiated by Glasgow Sculpture Studios and funded by public bodies, including housing associations, Strathclyde Regional Council and the then Scottish Arts Council, this work, like Wyllie's, emphatically reflects on decline.

Von Halem had noted the proliferation of various sites called 'works' on old maps of the ward, and the sculpture is a testimony to the labour history of local people, even though the buildings where they worked have disappeared.

The artwork is made from culled stone salvaged from demolition, and curves that have been locked together like railway branch lines. Maps of former works are embedded in bronze.

The Works (detail)

1993, sculpture by Sibylle von Halem (b.1963)

As somewhere that has long been subject to cycles of regeneration and the social sculpting of people, experiments in architecture and the carving up of communities to make space for roads, the sculptures that are here now reflect this upheaval.

A magnificent Doulton fountain, one of three in Glasgow, was modelled on the market cross, exactly where the Springburn Leisure Centre is now located. When the column was moved to Springburn Park it was separated from its ornate base, which has now been lost. At some point, the unicorn lost its horn. The column is subsiding and needs to be secured.

A sculpture by Andy Scott, The Bringer, stands outside the library and leisure centre. Installed in the 1990s, this is a muscular motif of regeneration, the trumpet symbolically heralding the rebirth of the area. Made in fibreglass, its surface is sadly dilapidated. Few local people would recognise this work as being by the same artist that made The Kelpies.

The Bringer is possibly Scott's earliest public sculpture. In an email to me, he lamented its current state and wondered why it had been painted black. I've noticed that this work is often used as seating. Pupils from the local Springburn Academy, who took part in a creative outdoor learning workshop with me, expressed genuine enthusiasm for it – once they had Googled Andy Scott.

An earlier work by Vincent Butler, Heritage and Hope, has been languishing for well over a decade at Powderhall Bronze in Edinburgh since it was vandalised. Butler was so upset that he paid for the work to be removed and taken to the foundry for repairs. The plinth in front of the Carnegie Library building (which is no longer a library) has remained empty, and Butler left clear wishes not to reinstate the work here.

'Heritage and Hope' in store at Powderhall Bronze, Edinburgh

1989, bronze sculpture by Vincent Butler (1933–2017)

As part of an artist's residency in Ward 17 in Glasgow, I am arranging to bring the repaired Heritage and Hope back temporarily to the local shopping centre, for the community to consider a new site.

This will be an interesting process, since Springburn is now one of the most diverse parts of the city, and is home to many former refugees. What do 'Hope' and Heritage' mean to people who live here now?

Mandy McIntosh, artist

This content was supported by Creative Scotland