(b Løten, 12 Dec. 1863; d Oslo, 23 Jan. 1944). Norwegian painter and printmaker, his country's greatest artist. He began painting in a conventional naturalistic manner, but by 1884 he was part of the world of bohemian artists and writers in Christiania (now Oslo) who outraged bourgeois society with their advocacy of sexual as well as artistic freedom; Christian Krohg, who gave him informal tuition, was in particular his early mentor. In 1885 he made the first of several visits to Paris, where he was influenced by the Impressionists and Symbolists and, above all, by Gauguin's use of simplified forms and non-naturalistic colours. Soon after his return he painted the first work in which he showed a distinctly personal vision, The Sick Child (1885–6, NG, Oslo).

Read more

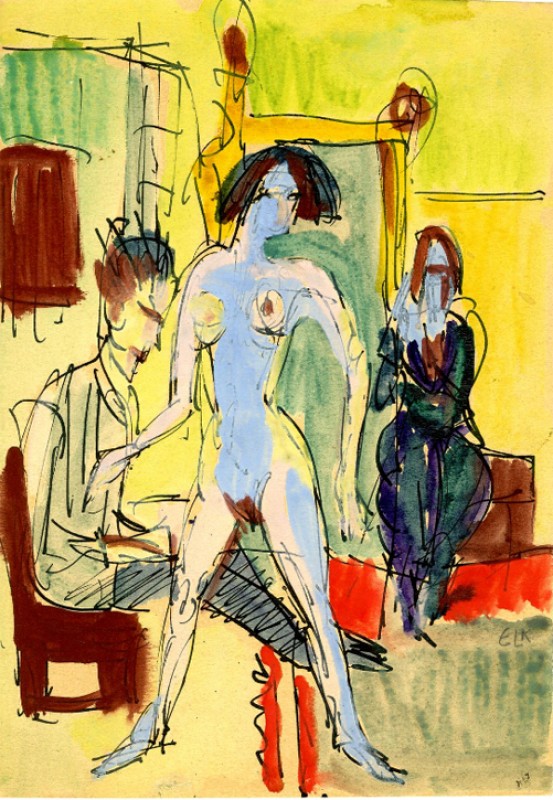

The choice of subject was highly significant, for it reflected his own traumatic childhood (his mother and eldest sister died of consumption when he was young, and as a result his grief-stricken father became almost dementedly pious). ‘Illness, madness, and death were the black angels that kept watch over my cradle’, he wrote, and in his paintings he gave expression to the neuroses that haunted him. Certain themes—jealousy, sickness, the awakening of sexual desire—occur again and again, and he painted extreme psychological states with an unprecedented conviction and an intensity that sometimes bordered on the frenzied.In 1892 Munch was invited to exhibit at the Verein Berliner Künstler (Association of Berlin Artists) and his work caused such an uproar in the press that the exhibition was closed. The scandal made him famous overnight in Germany, so he decided to base himself there and from 1892 to 1908 he lived mainly in Berlin (although he moved around restlessly, staying in boarding houses, and made frequent visits to Norway as well as journeys to France and Italy). During this period—the heart of his creative life—he devoted much of his time to an ambitious open-ended series of pictures that he called the ‘Frieze of Life’—‘a poem of life, love and death’. The most famous of the paintings from the series, The Scream (1893, NG, Oslo), and several others were translated by Munch into etching, lithography, or woodcut. He was one of the greatest of all printmakers, and his woodcuts, together with those of Gauguin, played a major part in the 20th-century revival of the technique; they are often in colour and exploit the grain of the wood to create a sense of rough, intense vigour.In 1908 Munch suffered what he called ‘a complete mental collapse’, the legacy of heavy drinking, overwork, and a wretched love affair, and after recuperating he made his home permanently in Norway, where he was by now an honoured figure. He realized that his mental instability was part of his genius (‘I would not cast off my illness, for there is much in my art that I owe to it’), but he made a conscious decision to devote himself to recovery and abandoned his familiar imagery. The anguished intensity of his art disappeared and his work became much more extroverted. He announced this change of direction in a series of murals decorating the Assembly Hall of Oslo University (1910–16): they are concerned with what Munch called ‘great eternal forces’ (History and The Sun are two of the titles) and they are strong and fresh in colour and optimistic in spirit. In 1916 he bought a large house called Ekely, at Skøyen on the outskirts of Oslo, and he spent most of the rest of his life there, leading an increasingly isolated existence, although he continued to travel a good deal. His subjects in his later years, during which he kept up a prodigious output, included landscapes, portraits (he made much of his living through commissions), and workmen, often seen trudging through snow. However, he sometimes returned to the themes that haunted his youth, and occasionally he rekindled the passion and profundity of his early years, as in the last of his numerous self-portraits, Between the Clock and the Bed (1940–2, Munch Mus., Oslo), in which he shows himself old and frail, hovering on the edge of eternity. At his death he left a huge body of his work to the City of Oslo to found the Munch Museum (opened in 1963 to mark the centenary of his birth). Munch ranks as one of the most powerful and influential of modern artists. His impact was particularly strong in Scandinavia and Germany, where he and van Gogh are regarded as the main sources of Expressionist art. The intensity with which he communicated mental anguish opened up new paths for art. ‘Just as Leonardo da Vinci studied human anatomy and dissected corpses’, he said, ‘so I try to dissect souls.’

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)