Once considered among the more conservative and traditional forms of art, painting is currently at the most adventurous and challenging it has ever been.

That is the simple but ambitious argument put forth by the latest Hayward Gallery exhibition, 'Mixing It Up: Painting Today', on view until 12th December 2021.

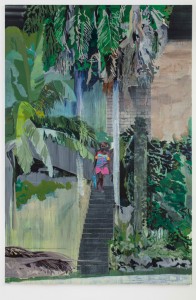

Ascent

2019, acrylic on paper laid on board by Hurvin Anderson (b.1965)

A wide-ranging survey of contemporary painting made within the last decade, the exhibition seeks to share the recent works of UK-based artists, all of whom showcase a dynamism and diversity of thought.

From artists who are well established in their careers to ones who have recently graduated from art school, all manner of styles and influences are represented in the sprawling two-storey exhibition at the Southbank.

What immediately stands out is how the artists in the exhibition play with the characteristics and techniques of the medium, using knowing nods to the historical significance of painting to actively recreate and redirect artistic traditions.

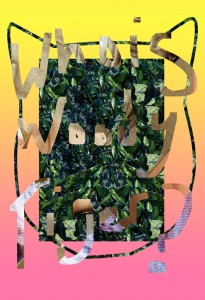

Cameo

2021, oil on linen by Louise Giovanelli (b.1993)

Louise Giovanelli captures the multifariousness of human emotion as seen in film stills such as Cameo (2021), in which a glamorous film star is caught in an unguarded expression.

Using a pointillist technique, Giovanelli's layers of paint bring depth to the multitude of emotions in a freeze-frame: shock, disgust, confusion, and eroticism pour out from her contorted facial features.

It's overwhelming yet mysterious, offering nothing by way of context, being tightly cropped and framed within a small canvas measuring a mere 25 cm by 35 cm. Isolating this scene from any context, it becomes a purely meditative experience of contemplation of the subject's emotions. The decision to paint a film still adds an intermediary layer, a filtration that reveals the limits of expression and capturing of human emotion.

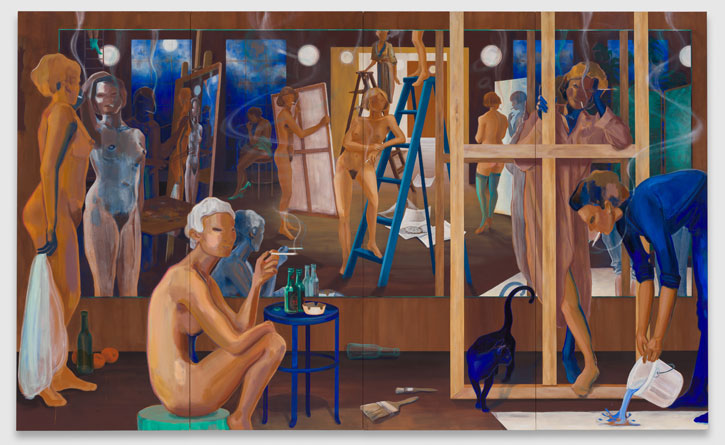

Smoke and Mirrors

2020, ink, gesso, synthetic tempera, chalk, oil pastel & oil on canvas by Lisa Brice (b.1968)

Historically an object of the male gaze on the canvas, the woman's body has also been recentered in the works of South African artist Lisa Brice.

In Smoke and Mirrors (2020), Brice draws from the depictions and poses of women by (male) Impressionist artists Degas, Manet, and Picasso, but recasts them in sites that are typically viewed as sites of misogyny or sexual harassment, for example, gyms or train carriages. The women engage deeply in their own worlds while unclothed, and it seems as though Brice has freed them from the projections of the male gaze in this sanctuary.

Yet while their everyday activity – bathing and getting dressed, for instance – is stripped of their sexual connotations, still the women feel the need to partly conceal themselves in shadows.

Brice uses a special blue hue she developed over years of interest in neon advertising to illustrate the silhouettes of their feminine figures. She re-reveals the multidimensionality and complexity of the woman as a person with her own insecurities that extend beyond that associated with a male perception.

Though the artists featured dispel with long-held traditions, they still refer widely to them. The emphasis on the British empire and colonialism's effect and influence on artists featured, in particular, imbues their paintings – the preferred medium for stately portraits during that era – with a poignant, if not bittersweet irony.

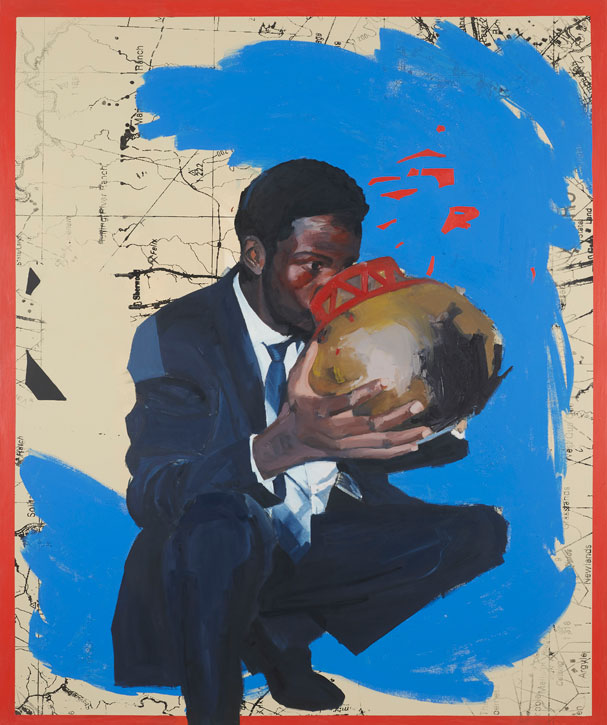

Bira

2019, oil on canvas by Kudzanai-Violet Hwami (b.1993)

Kudzanai-Violet Hwami's work emphasises her transnational identity by subverting the mythologies associated with techniques such as overpainting. A recent graduate of the Ruskin School of Art, Hwami's work navigates her youth, splintered across several countries, having moved from her native Zimbabwe to South Africa and subsequently to the UK.

Bira (2019) features a young man drinking from a container in his oversized hands, the ritual beer consumed as part of the traditional bira ceremony. Underpainted with a map of colonial Rhodesia made by a man nostalgic for it, Hwami acknowledges the independence of Zimbabwe from its colonisers whilst acknowledging the reality that it continues to loom over the man, who's trapped between deeply entrenched colonial attitudes and a desire to reclaim his traditional roots and practices.

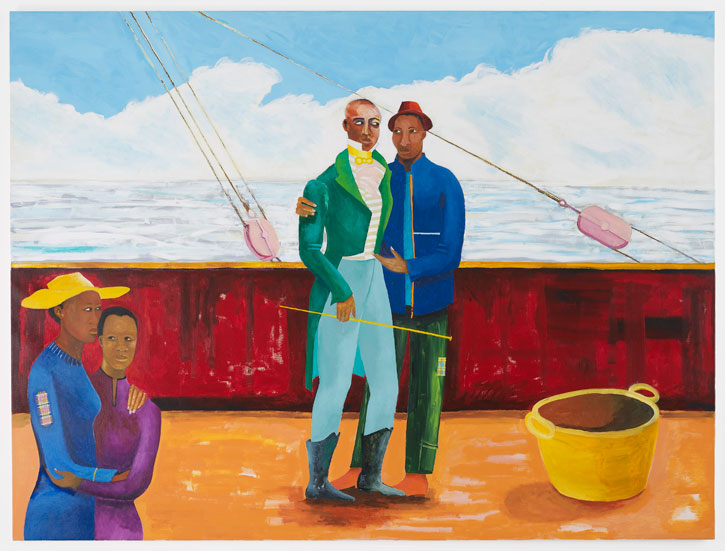

The Captain and The Mate

2017–2018, acrylic on canvas by Lubaina Himid (b.1954)

Lubaina Himid's The Captain and the Mate (2017–2018) is another postcolonial highlight. A continuation of her long series of works recasting figures from the works of the nineteenth-century artist James Tissot, who was focused on the costumes and dress of his subjects, Himid's work features a typical colonial setting of a ship's deck. The ornate clothing of the ship patrons is centre stage, but white figures are recast as black and brown. History is being retold; previously sidelined characters are literally centred.

Himid's faithful reproduction of the original ship plays with the antiquity and importance of portraiture in that era by subverting the historical racial hierarchy while preserving the same historical context.

The immersiveness of each canvas and series in the exhibition, replete with stories and contexts, beckons the viewer into rich narratives, worlds, and dreams created by the artists from deeply personal lives and memories.

Matthew Krishanu's Two Boys (Church Tower) (2020), part of a series where he features himself and his brother as children, is one example.

Two Boys (Church Tower)

2020, oil on canvas by Matthew Krishanu (b.1980)

A reflection of his dual upbringing in Dhaka and Bradford, he pieces the image together from photographs and memories of childhood. It represents a moment in time memorialised, depicted distinctly as a nostalgic recollection rather than a photorealistic memory.

Dreamlike and blurry, the edges and details are faded, fuzzy and capturing the warmth of the mood and the temperate climate. In the boys' expressions there is a curiosity and earnestness. But simultaneously there is a stoic contemplation in the boys' poses – a pause between instances of displacement and uncertainty in their nomadic childhood.

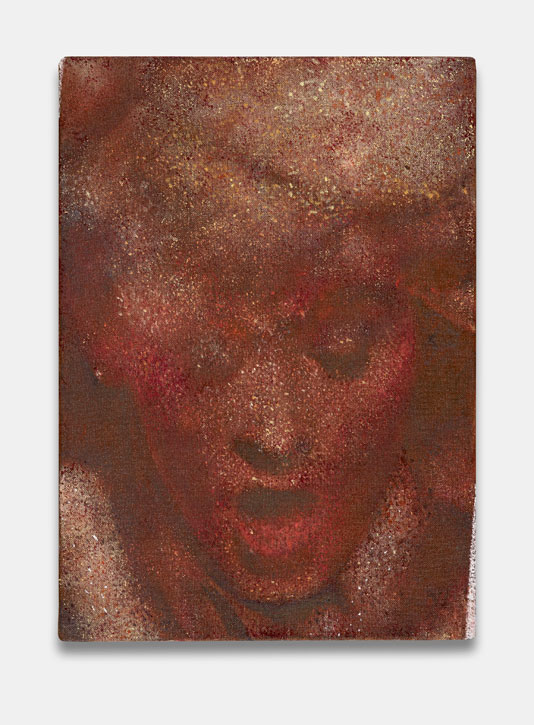

Focusing such immersiveness in the broader mythological power of a crowd is Oscar Murillo's manifestation (2019–2020).

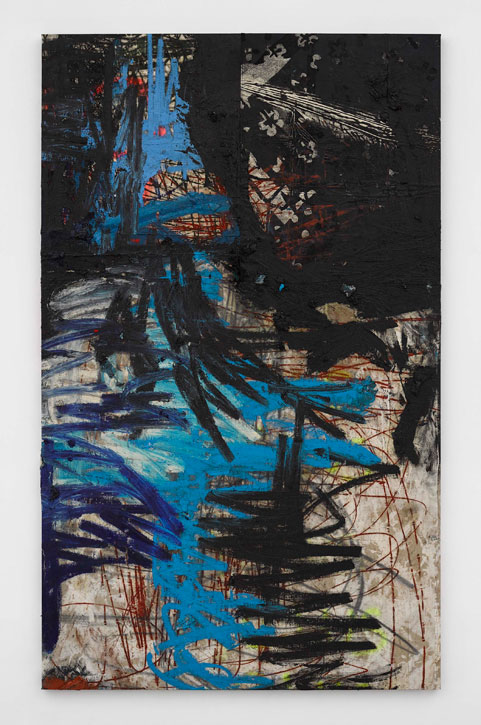

manifestation

2019–2020, oil, oil stick, cotton thread & graphite on canvas, velvet & linen by Oscar Murillo (b.1986)

His poetic and abrasive, sprightly abstraction is gestural, made by sweeping movements of his body over the large canvas. Painted during lockdown, the works in this series point to the various crises that have spawned political movements in the last two years.

The titular manifestation is a burst of energy – 'manifestation' has a political connotation in languages including French. The Gilets Jaunes – or yellow vest protestors in France – recognised by their unmistakable sea of vibrant colours and display of dissent with arson, is translated here in deep, vibrant hues. Murillo's gestures on the canvas become a political signifier – the use of one's body in dissent, quite literally in a movement.

'Mixing It Up' is a sprawling ode to the vibrancy of British contemporary painting, proving that identity has endless bounds of reference on an easel. Not only are longtime traditions and techniques being masterfully redefined, but the international nature of contemporary painting also shows that the medium is on its way to no longer being the exclusive preserve of the white Western elite. The exhibition proves that the medium is being defined by one's class, race, and country of origin – not as a means to gatekeep, but as a rich source of inspiration.

Ashley Tan, freelance writer

'Mixing It Up: Painting Today' is on at Hayward Gallery, London from 9th September to 12th December 2021