'But she was earnest with me to declare which of them I judged fairest. I said "She was the fairest Queen in England and mine the fairest Queen in Scotland."' – James Melville, Scottish ambassador, 1564

Mary, Queen of Scots

early 17th C

British (English) School

Mary, Queen of Scots (also known as Mary Stuart) – like her cousin, Elizabeth I of England – has intrigued historians, writers, poets, playwrights, and painters for centuries. Her tragic fate, a consequence of her tumultuous relationship with the last Tudor queen, resulted in her being one of the most memorable historical figures of the age. Elizabeth is remembered as Gloriana and the Faerie Queen, Mary as a Catholic martyr. Yet portraits of the queens produced in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries illustrate striking parallels between the two women – especially Elizabeth’s well-known ‘fairy wings’, which were appropriated by Mary – reminding us that after all, they did share Tudor blood.

Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587)

c.1559

François Clouet (c.1515–1572) (follower of)

From a martyr to a siren to a traitor to a whore, representations of Mary Stuart remain wide and complex. Half-Scottish and half-French, she is remembered both as a Scottish queen and a French queen with

But tragedy soon struck, and François died suddenly in 1560. His mother, Catherine de' Medici, became regent for her next son, the ten-year-old Charles IX. Now a widow, Mary embraced her Scottish heritage and came back to her native Scotland.

Mary, Queen of Scots: The Farewell to France

1867

Robert Inerarity Herdman (1829–1888)

Mary, Queen of Scots Bidding Farewell to France, 1561

1851

William Powell Frith (1819–1909)

Both of these paintings are nineteenth-century portraits depicting Mary’s departure from France. Her sadness here is clear, and in many

Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587), at Fotheringhay

1929

John Duncan (1866–1945)

Her return was not to be a happy one. Due to a fair amount of misguided decisions, in 1568 Mary was forced to abdicate and leave her homeland, heading to her greatest enemy’s kingdom, England. This was where Mary spent eighteen years of her life as a prisoner, at the mercy of Queen Elizabeth’s goodwill. Mary forged her reputation as a traitor and conspirator against both England and Protestantism with her constant correspondence to France and Spain, in which she begged to be rescued and insisted she

Over the centuries, portrayals of Mary as a martyr wearing black increased, with French playwrights using these portraits as a basis for costumes assigned to the actresses playing Mary, Queen of Scots on stage.

There’s a striking resemblance between the dress in this portrait, which was painted in the seventeenth century, and the costume worn by the actress who played Mary Stuart in Pierre-Antoine Lebrun’s 1820 tragedy (based on Schiller's 1800 play). The gold and black dress

Preparatory Sketches of Mary, Queen of Scots and Lord Darnley

c.1854

Richard Burchett (1815–1875) (studio of)

To some extent, one could say that the costumes, in turn, inspired some representations of the Scottish queen and her second husband, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, which were painted in the second half of the nineteenth century. Mary’s representation as a chaste Catholic martyr undoubtedly dominated the ways in which she was perceived by nineteenth-century artists and playwrights.

Mary, Queen of Scots has become a symbol of both Catholicism and martyrdom. The above portrait – which was commissioned by one of Mary’s ladies, Elizabeth Curle – is entitled The Memorial Portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots, and Marguerite A. Tassi, an English professor and an expert in representation, has argued that this portrait played a crucial role in how Mary was remembered after her death, mainly by the Catholic community (see her chapter in The Emblematic Queen).

For some, Mary was also seen as a more sexual creature. Debra Barrett-Graves, another English professor

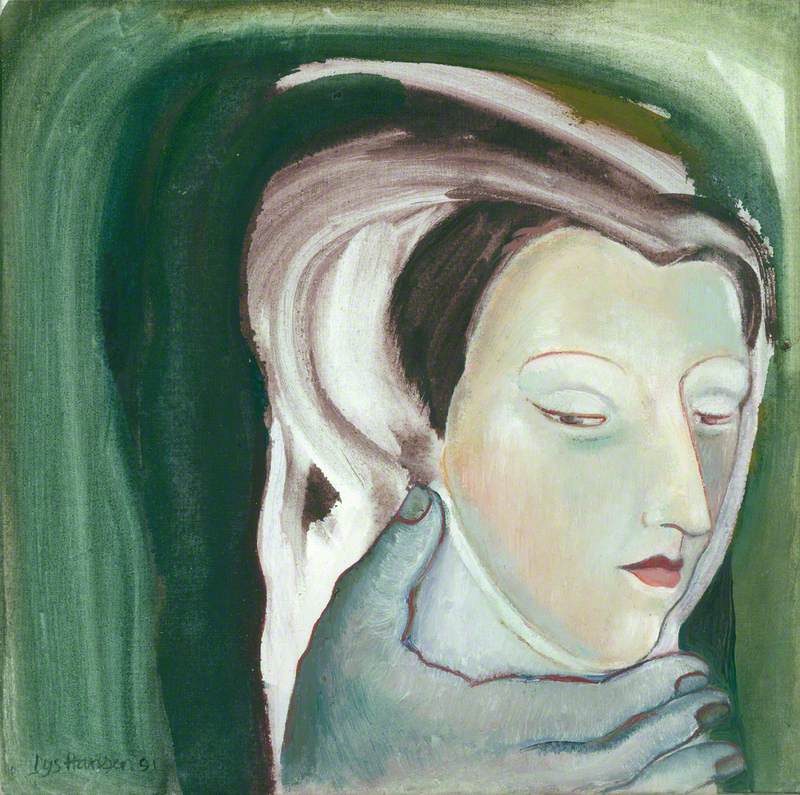

By the early twentieth century, Mary, Queen of Scots’ head is more or less the only thing left in representations of her – portraits are painted to remember her execution, and what many people see as being her tragic death.

Even in this painting – dated 1934 – Mary’s head is what catches the viewer’s eye. Here, she is the lost queen of Scotland who was executed for treason by her English cousin. Interestingly enough, Mary Queen of Scots is still very much cherished by her native Scotland, a country that chose to have a Calvinist reformation as early as 1560 and which would despise any Catholic rites or icons.

Overall, Mary, Queen of Scots’ martyrdom and religious piety has dominated the ways in which she has been remembered in the arts. In the twenty-first century, Mary and Elizabeth (as one cannot completely be understood without the other, or so it seems) are receiving even more media attention with the upcoming movie, Mary, Queen of Scots, directed by Josie Rourke and starring Saoirse Ronan as Mary and

In my opinion, the story of Mary Stuart, whose life is entangled with Elizabeth’s, will continue to inspire new writers, poets, painters, screenwriters, playwrights, historians, and the public, for centuries to come.

Estelle

Further reading

Debra Barret-Graves (ed.), The Emblematic Queen: Extra-Literary Representations of Early Modern Queenship, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013

Antonia Fraser, Mary Queen of Scots, Delta Books, 1969

John Guy, My Heart Is My Own: The Life of Mary Queen of Scots, Harper Perennial, 2004

Carole Levin (ed.) with Christine Steward-Nunez (associate ed.), Scholars and Poets Talk About Queens, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015

Alexander S. Wilkinson, Mary Queen of Scots and French Public Opinion, 1542–1600, Palgrave Macmillan, 2004