Visitors to the 2016 exhibition 'Modern Scottish Women' at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh may well have been struck by the large picture of card players in the first room – a space devoted to paintings produced around the turn of the twentieth century.

The painting shows three Spanish workmen at a table, intent on their game, under a darkening sky. In the foreground, the produce of the fields make an attractive still life of grapes, capsicums and watermelon. Impressionism and Symbolism make no impact upon this staunchly realist painting, and there is nothing similar in the gallery.

Indeed, to find anything remotely comparable to Mary Cameron's Les joueurs one would have to return to the Scottish National Gallery, and stop in front of Velázquez' An Old Woman Cooking Eggs.

This would not of course have been possible for Cameron since the early bodegón, a peasant kitchen or tavern scene, was only acquired by the gallery in 1955. Nevertheless pictures of this type were well known by the early years of the century and details from the latter had arrived in the former, in the shape of rustic pottery, shaved heads and the sensuous handling of white drapery.

Cameron, by 1907 when Les joueurs was exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Français in Paris, was a formidable late exponent of hispagnolisme, that brand of Caravaggesque Realism that originated in French painting 70 years earlier, when the galerie espagnole was thrown open to the public. The affection for Spanish art in Britain, and Velázquez in particular, has arguably, a longer history, but its impact on artists waited, for the most part, until after the Pre-Raphaelite interlude. There is no doubt that the attention devoted to 'Golden Age' painting dramatically increased as the nineteenth century drew to a close and Scots painters were in the vanguard. In this, the work of Mary Cameron provides a unique and fascinating case history – if only we knew more about it.

Mary Cameron (1864–1921) was born in Portobello, Edinburgh, the daughter of Mary (née Small) and her husband, Duncan Cameron, owner of a highly successful stationery company. Her father was patent holder for the 'Waverley' pen. A bright young woman, Mary Cameron attended the Board of Manufactures Academy in the early 1880s, and began exhibiting at the Royal Scottish Academy annual exhibitions in 1886. Travels to Norway, Holland and Paris followed, with regular return visits to the family home, now at Bonnyrigg. In Paris she was taught by three academic painters: Jean-André Rixens, Gustave Claude Étienne Courtois and the military painter and muralist, Lucien-Pierre Sergent.

From the start, she showed no inclination for the kind of domestic interiors and still lifes favoured by many women painters, opting instead for battle-pieces, perhaps led by the example of Lady Butler. These all seem to have disappeared. She also tried her hand as a courtroom artist, reporting on the Ardlamont Mystery case for The Oban Times in 1893. A keen horsewoman, she attended the Royal Dick Veterinary College in Edinburgh studying equine anatomy. Racing scenes and at least one notable portrait of a Master of Foxhounds followed.

However, a career serving the Lothian gentry with horse portraits was never enough for Cameron and in 1900 she went to Madrid explicitly to copy Velázquez at the Prado. This was not unusual in itself – John Singer Sargent, Arthur Melville, John Lavery and many others had already been there – but the results, copies of portraits of Infanta Margarita, the Don Balthasar Carlos and The Cardinal Infante Don Fernando as a Hunter reveal a mature artist still keen to learn.

The Cardinal Infante Don Fernando as a Hunter (after Diego Velázquez)

c.1900–1905, 81 x 49 cm by Mary Cameron. Private collection

In Madrid she made her first forays into the anterooms of the Plaza de Toros, painting the preparations, the bullfight and its aftermath in what amounts to her own tauromaquia. Surviving snapshots record a typical fight and her standing in the ring. She arrived at a time when there was much debate about the Spanish national sport. Travellers, mostly British and American, were drawn to the bullring following the local crowds and in those days, when horses went without body-armour, as many as six were shamelessly gored to death before the entry of matadors.

While other artists – Arthur Melville, John Lavery, Joseph Crawhall and George Denholm Armour – had painted such scenes before her, none entered into the process with the same gusto as Cameron. A founder member of the Edinburgh Ladies' Art Club may have been expected to sit well back and avert her eyes on such an occasion, but not her, and for this she was applauded by Spanish critics in 1902 in the magazine, Sol y Sombra. It was claimed that when the Spanish aficionados of the sport were pilloried as 'uncultured barbarians', this young woman was a 'beautiful, smart and stylish... supporter of bullfighting'.

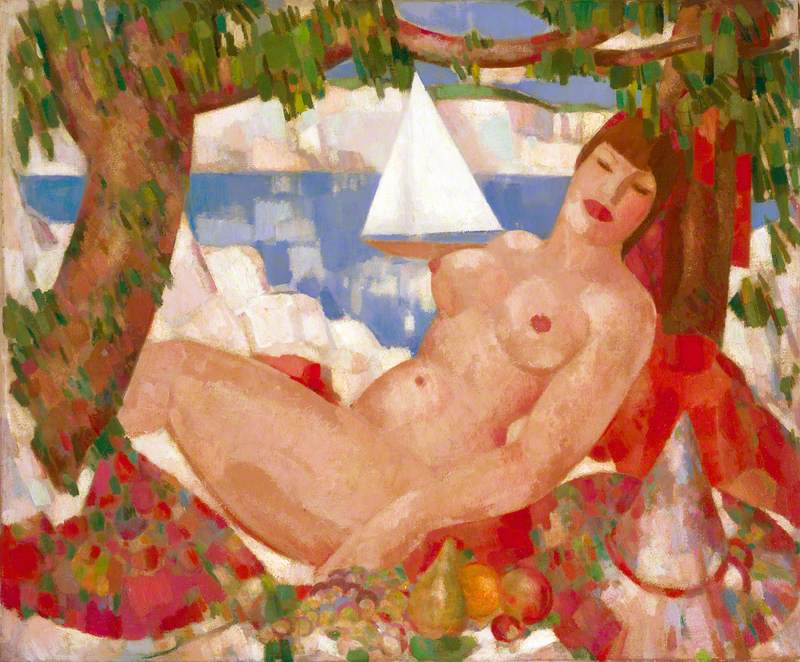

Picadors entrant dans la place des taureaux: Madrid

c.1900, 130 x 152 cm by Mary Cameron. Private collection

Considering the Picadors entrant dans la place des taureaux: Madrid, shown at the Salon of 1901, with its dead or dying horse, dragged bleeding from the arena, she must have relived those moments in the dissection room at the veterinary college. By 1904, having been awarded a 'Mention Honorable' by the Salon jury for Mme Blair et ses borzois – a painting that frankly recalls Buffoon with a Mastiff (Don Antonio el Inglés), then attributed to Velázquez – she was ready to move on.

Mme Blair et ses borzois

1904, 203 x 189 cm by Mary Cameron. Private collection

Painting dancers and street sellers in Seville, vagabonds on the high Castilian plain, and occasional landscapes and portraits, she was exhibiting regularly in Edinburgh, Glasgow, London and Paris. Her mentors were however, not in Edinburgh, but among Spanish artists of the generación del '98, and by this stage she had met Ignacio Zuloaga who at that point had recently taken a studio at Segovia.

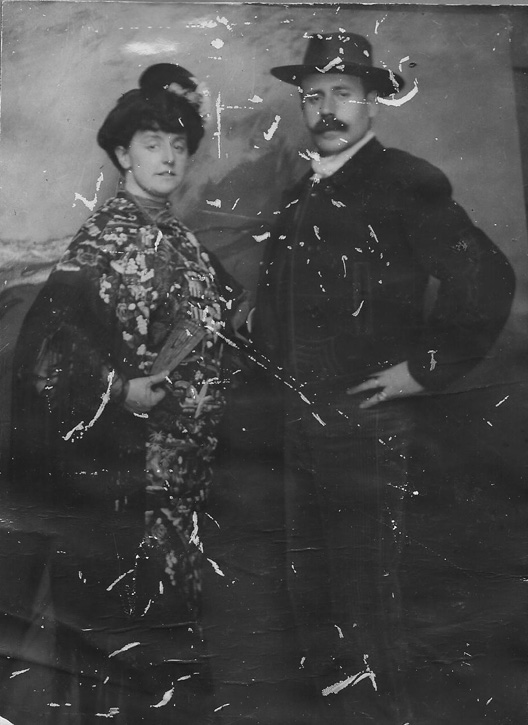

Mary and Snr Zuloaga

c.1905, photograph. Private collection

Although younger than Cameron, he already had an international reputation and was on the point of conquering the United States. Comparisons were frequently made between his and Cameron's paintings.

The Beggar

1907, 106 x 95 cm by Mary Cameron. Private collection

Les joueurs fits comfortably into Cameron's work of the period. As Elizabeth Cumming remarks in the 'Modern Scottish Women' catalogue, close examination of the picture surface reveals traces of a fourth card player, removed from the background. Comparisons with Meissonier on the one hand and Cézanne on the other, reveal how truly timeless Cameron's Castilian card players are. We find them as much in Zurbaran and Ribera as we do in the cinema of Luis Buñuel. And with manifestly successful compositions or figure groups like this, replicas and variants were occasionally made.

In this instance a smaller replica (in a private collection) was shown at the artist's large retrospective exhibition at the Georges Petit Gallery in Paris in 1913. This was to be Cameron's swan song. After the outbreak of war she substituted trips to Iona for the long Spanish sojourns, but by the end of it, her health was deteriorating, her decline hastened by a deeply unhappy marriage.

Exposition de Tableaux par Miss Cameron

Galleries Georges Petit, 8 rue de Séze, Paris, February 1913, installation photograph (replica of 'Les joueurs', top left)

Yet although she had no kindred spirits among the 'Edinburgh Ladies', the art Cameron admired was not without its local enthusiasts. In 1907 and 1908, the Old Master collection formed by Arthur Sanderson, the Edinburgh whisky baron, reputedly containing five works by Velázquez, was going through the salerooms, while among the new generation of collectors, Patrick Ford demonstrated his 'Spanish' sympathies in his choice of Lavery for family portraits. It was he who acquired Les joueurs, and hung it on the staircase of Westerdunes, his golfing retreat at North Berwick. The canvas was only donated to the Scottish Modern Arts Association in 1936, after the house was sold. By that stage, sadly, Mary Cameron was fading from collective memory.

Kenneth McConkey, art historian and Art Detective Group Leader: British 20th C, except portraits

Further reading

Alice Strang, ed., Modern Scottish Women, Painters and Sculptors 1885–1965, 2015 (exhibition catalogue, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh)