If you've seen The Real Marigold Hotel or Eat, Pray, Love, you will have a taste of what it could be like to travel to modern India. In a similar way, Marianne North's paintings transport us to exotic locations in Victorian times when travelling was not for the faint-hearted.

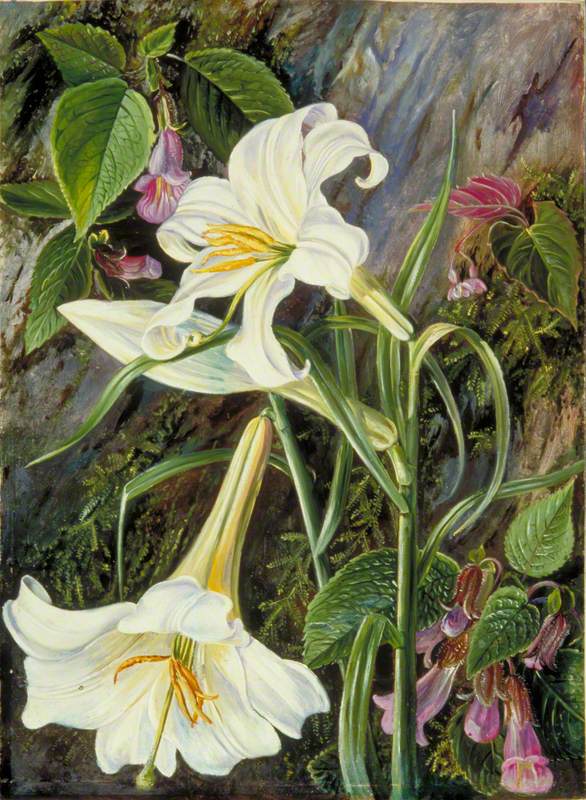

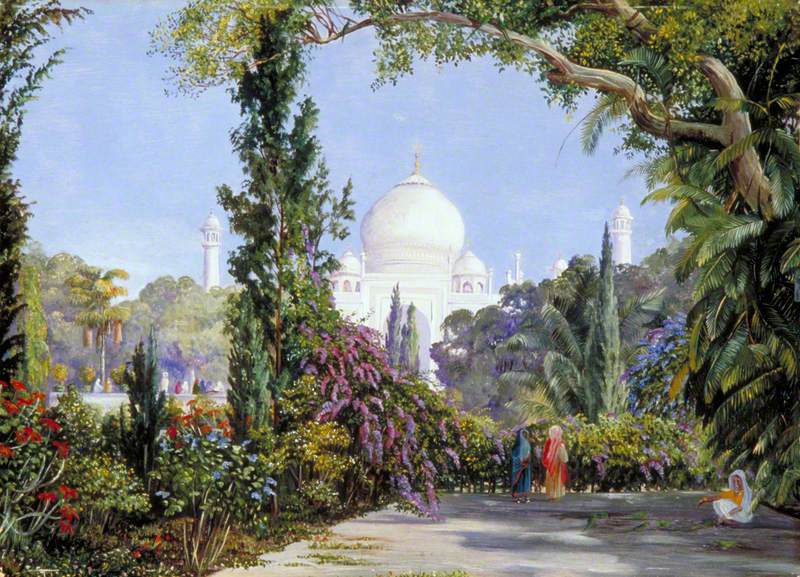

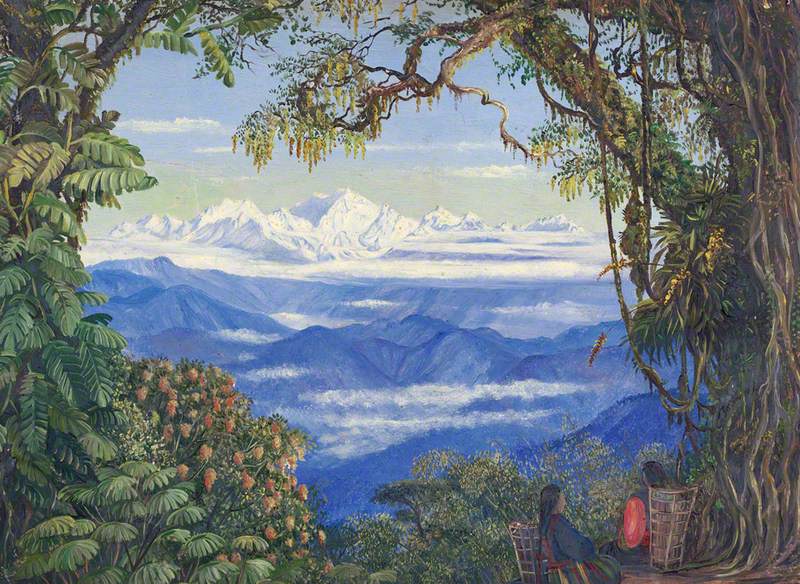

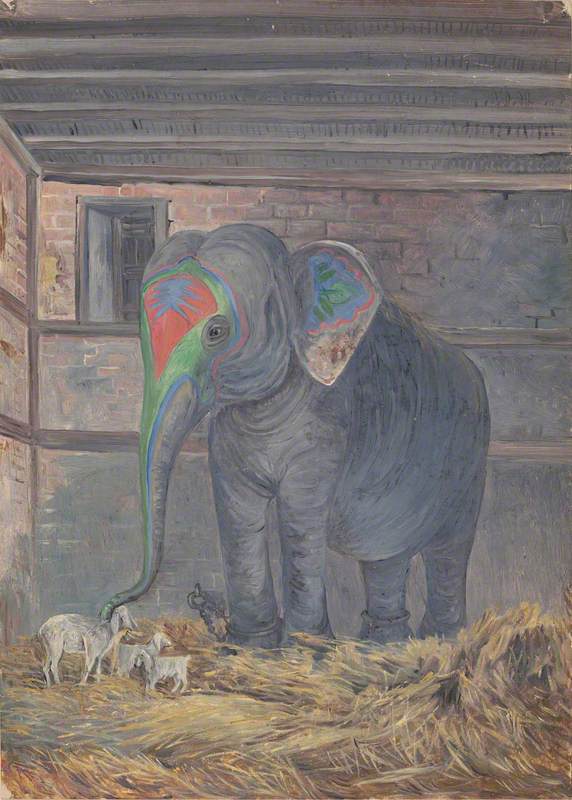

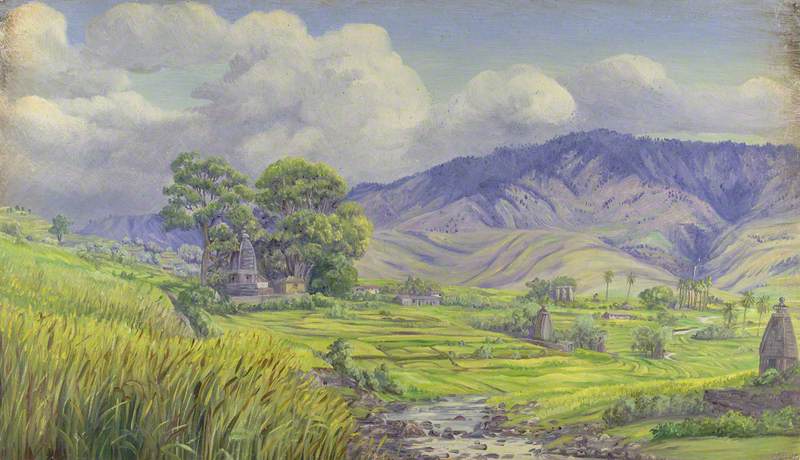

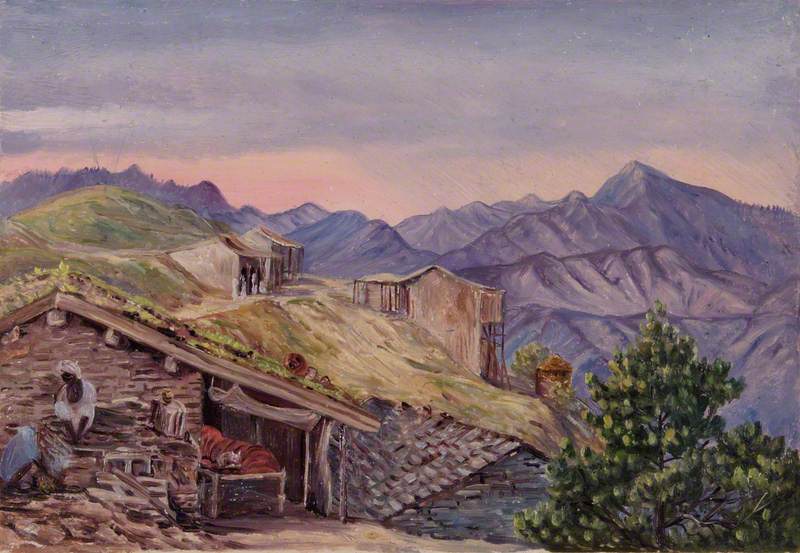

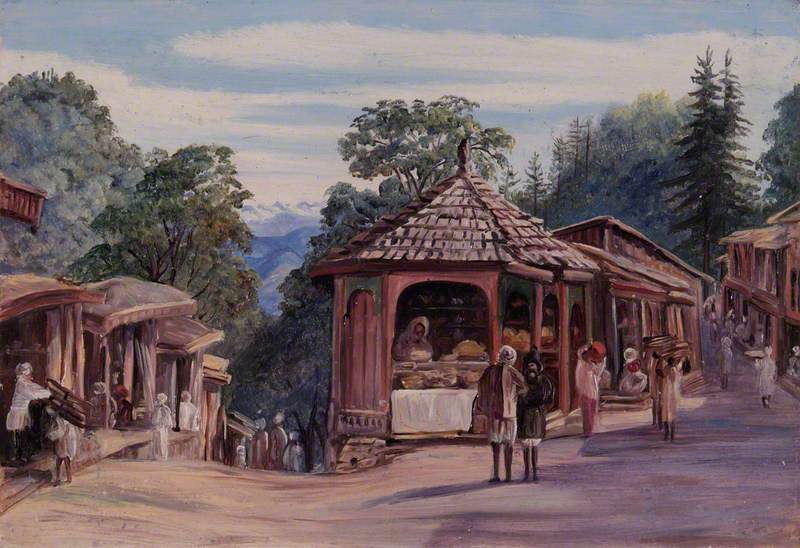

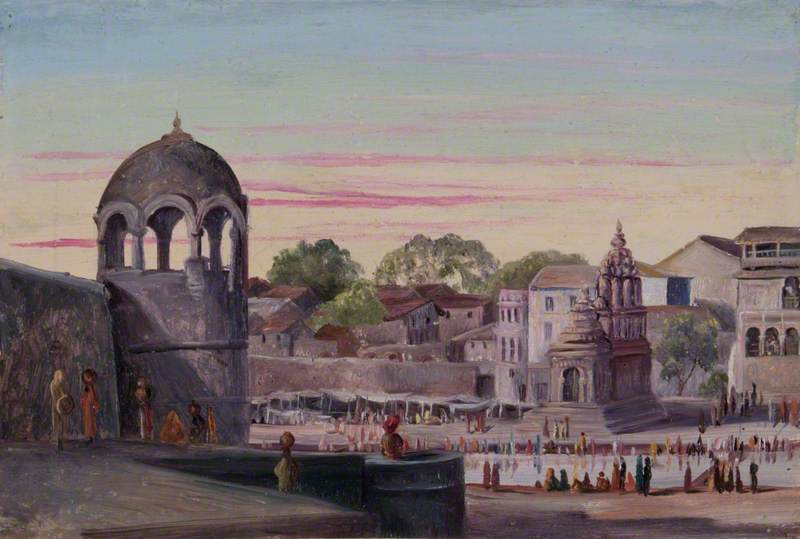

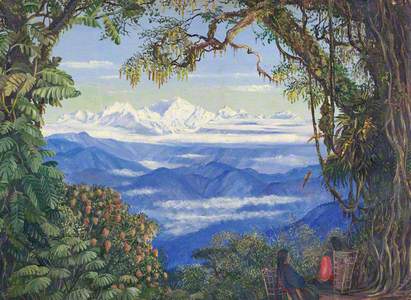

Marianne North's diaries reveal how overcoming obstacles almost seemed to inspire her to paint. From 1877 to 1879, she travelled alone through isolated rural places from southern to northern India, and endured often uncomfortable and even potentially dangerous situations. Nonetheless, Marianne stuck by her primary purpose – capturing on paper the essence of the places she visited. Marianne's persistence enabled her to not only produce amazing landscape paintings of flowering plants in situ, but to study temples, village scenes, and the people in and around Calcutta (now Kolkata), Bombay (now Mumbai), Delhi, Darjeeling, Jaipur and often much further afield.

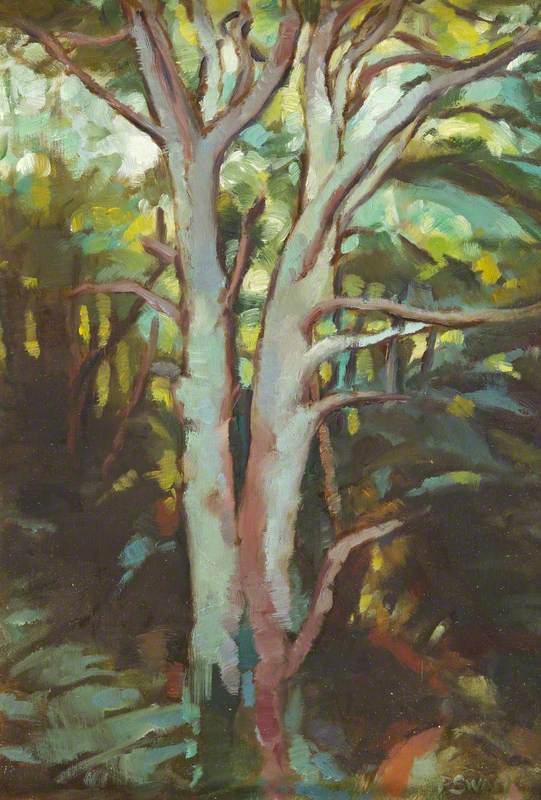

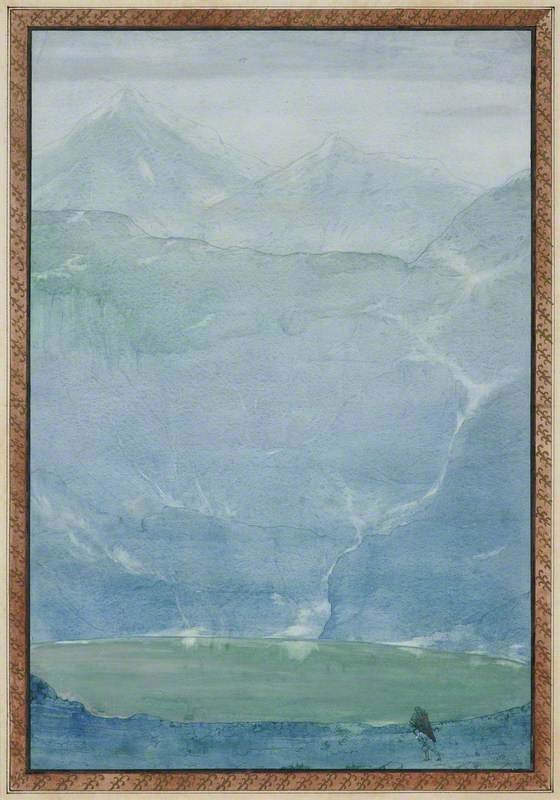

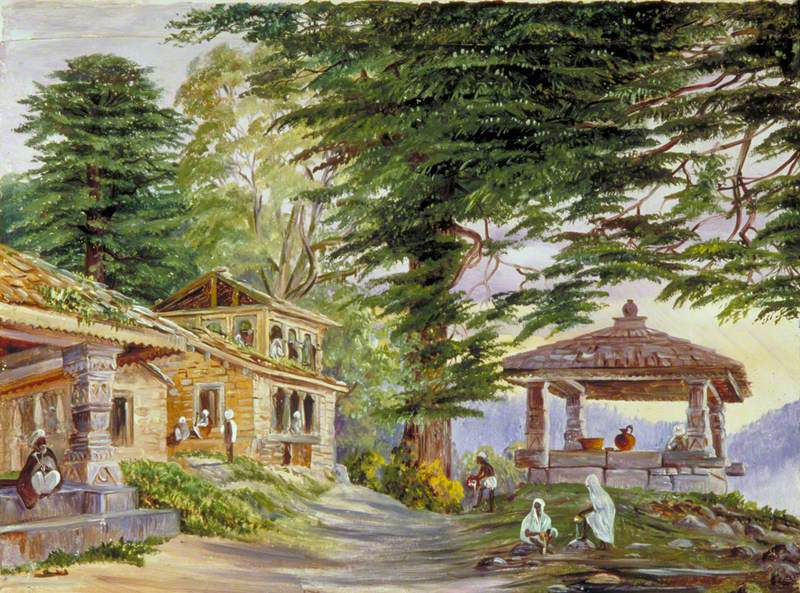

Dibee Dhoora Dee with Its Well and Deodar Trees, Kumaon, India

c.1878

Marianne North (1830–1890)

Marianne travelled as a happy nonconformist, rejecting traditional women's roles. With letters of introduction, and on her own terms when she got to her destination, Marianne stayed as a guest with high ranking or distinguished politicians, military personnel, doctors, and judges. Yet she expressed disinterest in participating in the expected social customs – keeping to her goals of pursuing and recording some of the most exotic plants found anywhere. Her observations as an outsider contributed to vividly coloured paintings, hastily sketched at first on site and embellished later.

While abroad, living her life free from convention, Marianne embraced practicality and humility. Baffling some she met, Marianne did not like a fuss but wanted the freedom to decide what she liked. On more than one occasion she described meeting her hosts or attending a gala dressed only in a simple dress she used to paint in. Even when meeting a Maharaja, she was in her 'old sketching clothes, and had not expected any such honours [as being received by him], but I always do as I am told,' as if taking pleasure in rebelliously turning up in ordinary work clothes.

Marianne North

photograph, albumen print, 1877 by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879)

With patience and open-mindedness, Marianne got the best out of sometimes difficult circumstances. Perhaps being carried from place to place on a platform on the shoulders of locals gave her the space to see things differently. The warring 'Tonga' carriers when travelling from Matapolium to Kunur proved a particular challenge. Apparently, they insulted each other and fought, while she patiently sat nearby in a place with a beautiful view. When they made up, continued the journey and sang while tossing flowers at her feet, Marianne realised that it had been a harmless diversion for them.

Marianne often approached life's small dramas with calm and a sense of humour. She attempted to paint the ancient buildings outside of Nasik when she was overcome by ants '...which seemed to have an especial taste for oil-paints, and they ate a good deal of me up too on their way to my palette.'

Even for the modern traveller, pleasant accommodation can fire the imagination. The hotel at Kunur consisted of a cluster of small bungalows with terraces and gardens. To Marianne's delight, she had one all to herself and it was luxuriously furnished. At Simla, her window had a memorable view that 'looked over endless hills, with great deodara branches, their stems and cones for foreground.'

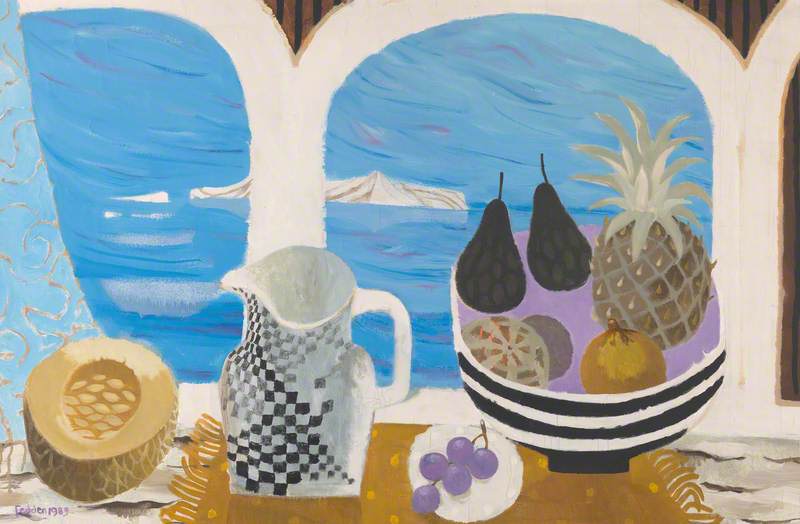

Marianne also had an eye for quality, and appreciated well-made genuine objects, but remained thrifty and avoided tourist traps. After seeing the beautifully engraved metalwork at Moradabad, Marianne thought the silver jogs in Lucknow less attractive in workmanship and 'of European shapes taking the place of their pretty lotas and chatties.'

Pair of cast brass vases, engraved with mythical and real animals, and inlaid with colour

19th century, from Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India

In Calcutta she didn't like shopping in a 'grand official way', preferring instead to go with her unassuming guide to where the difficult-to-find Dacca muslin was made, seeing 'the looms at work', and where it cost half the price as in the bazaar.

India No. 4

from 'Dickinson's comprehensive pictures of the Great Exhibition' (1854) vol. 2, plate V, illustration by Joseph Nash (1809–1878)

An exceptionally attractive place will often encourage a traveller to think about living there. While wandering around the bougainvillea and scarlet and orange bignonias in the garden belonging to the old Palace at Amristar, Marianne reflected on restoring and living in it. Then she came back to reality in a humorous way: 'but probably the white ant would have already loosened all the nails, and the roof was more likely than not to come tumbling in before long.'

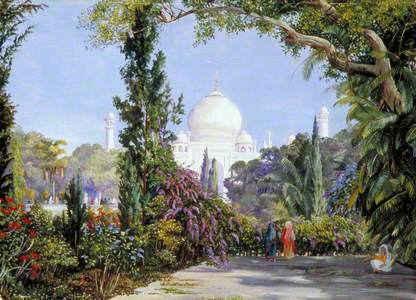

Old Palace and Garden, Amritsar, Punjab, India

1878

Marianne North (1830–1890)

Like any savvy traveller today Marianne relied on her intuition when dealing with people. She did not feel comfortable when a family approached her aggressively begging while she was sketching near Tughlakabad, so she pretended not to understand the language. When a Rajput noble on a hunting procession passed a lake where she was painting, Marianne hid behind rocks. Her explanation: 'such grandees have a habit of demanding anything they have a fancy for, and have no idea of being refused, while I had no idea of giving away the sketch I had come so far to make.'

In many ways, Marianne North was a woman ahead of her time, and her approach to travelling and looking at life was distinctly modern. She seemed to trust her feelings based on her own observations rather than what others told her; in that way, her journeys were authentic. The impact of Marianne's travels through India becomes clear when one considers her wonderful lasting legacy – an Asian-inspired gallery designed as a bungalow, filled with wonderfully vivid botanical paintings exactly as she had arranged them in The Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew.

Nancy Lyons, researcher and writer

Further reading

S. Morgan (ed.), Recollections of a Happy Life: Being the Autobiography of Marianne North, vol. 1 & 2: 1993 & 2012

A. Huxley, A Vision of Eden: The Life and Work of Marianne North, Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, 1980