For many of us, Easter means indulging in a seasonal chocolate binge. Whether it's an egg, a bunny, or an elaborate box of goodies, there's a good chance the name on the box will be Cadbury's.

But as you rip into the packaging, spare a thought for the artist who designed it. Whilst nowadays the artwork is typically digitally generated, in the 1930s Cadbury's considered chocolate box design to be worthy of established painters and designers.

Cadbury's saw an opportunity to become a leading light in product design, at a time when it had been in the doldrums in Britain for over a decade.

In 1923, the Royal Society of Arts had tried to address the crisis with a competition for textile, furniture, book covers, pottery and glass design. The event was sponsored by leading manufacturers of the time.

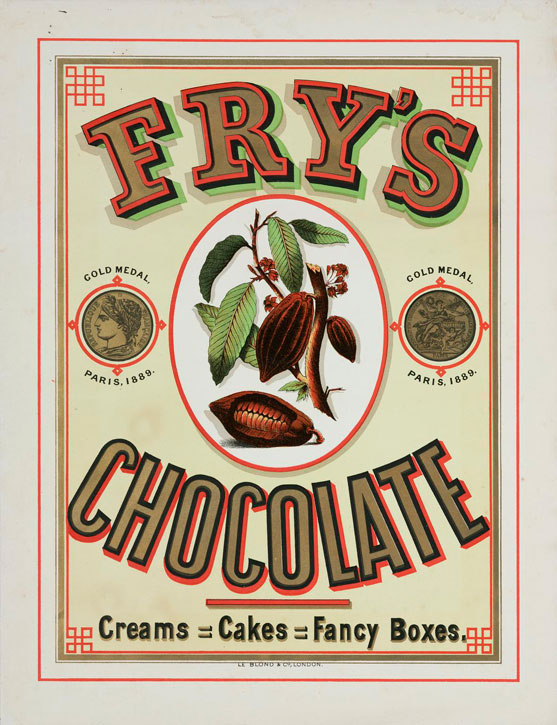

Fry's Chocolate Creams = Cakes = Fancy Boxes.

chromolithograph poster, Le Blond & Co, London

J. S. Fry & Sons, a subsidiary of Cadbury's, suggested adding a category for chocolate box designs, for which Cadbury offered a travel scholarship of £50, with Fry offering smaller prizes for box lid designs.

But not everyone was happy. The Times art critic noted sceptically:

'Time was when "chocolate box" was a term of artistic reproach; nowadays we invite the flower of our art schools to apply their talents and training to chocolate box decoration.'

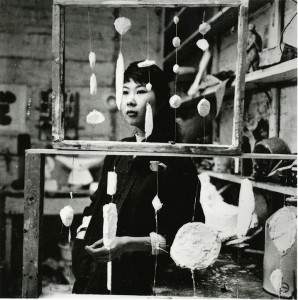

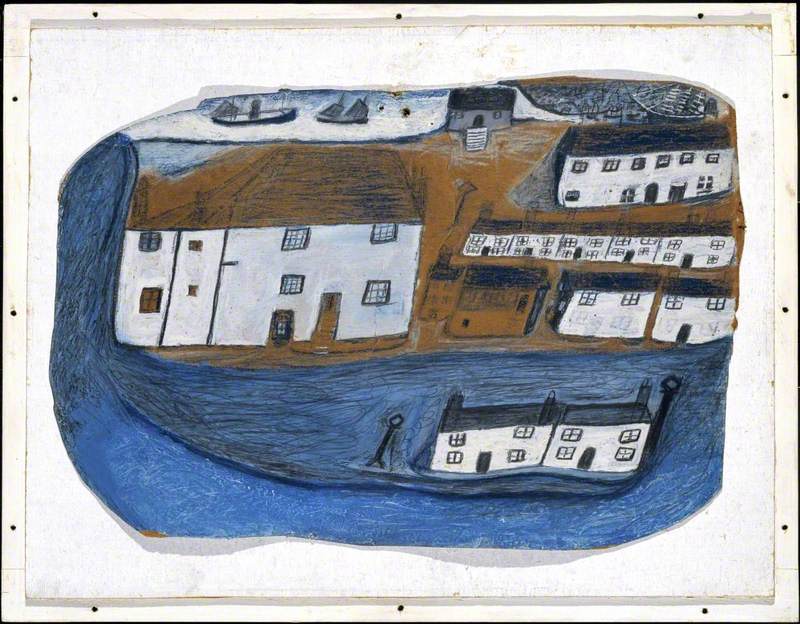

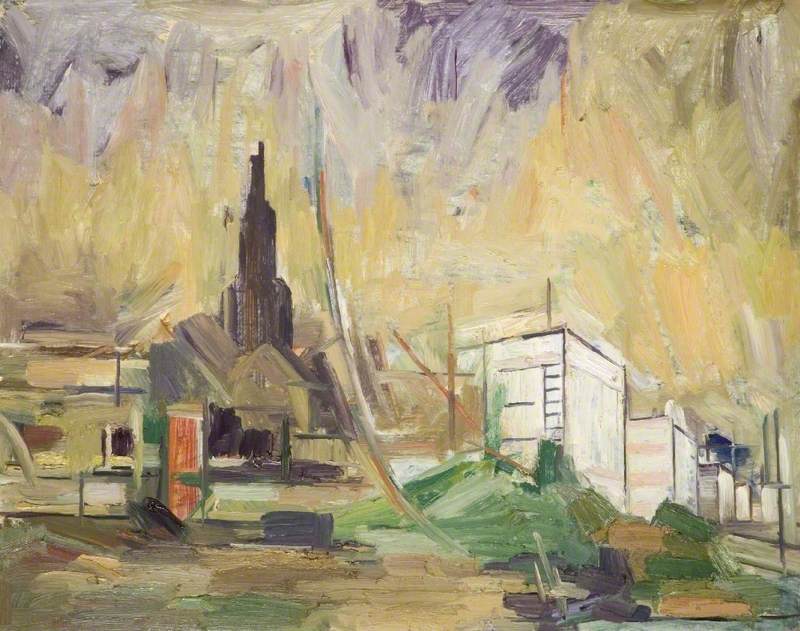

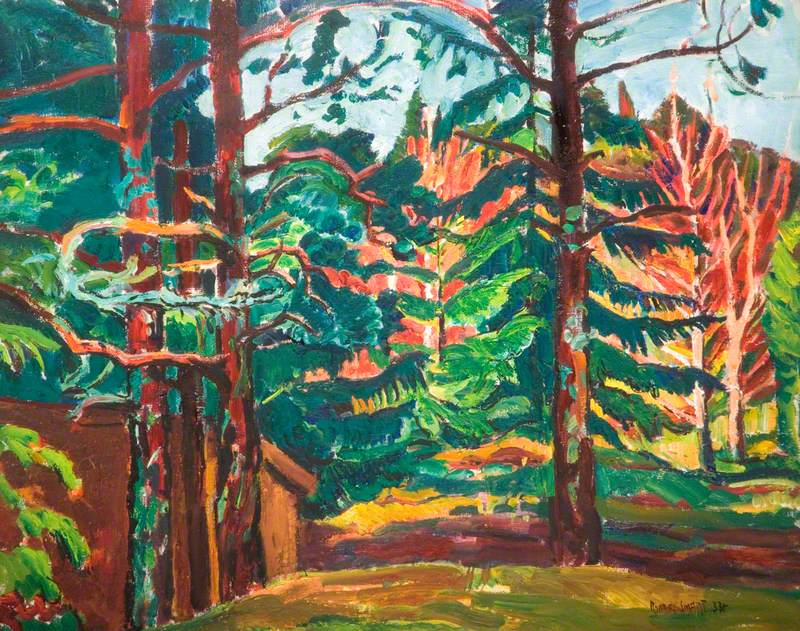

The first recipient of the scholarship was Rowland Hilder, a Goldsmiths student who won with a line drawing of an old sailing ship. He used his prize to travel to the Netherlands to pursue his interest in marine and landscape painting. This watercolour on paper below depicts a more local example of his work.

Hilder also worked as a book illustrator for Oxford University Press, winning an award for his drawings for Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island in 1929. Alongside his wife Edith, they created the enormously popular Shell Flowers of the Countryside series.

Despite the influence of Frank Pick – the legendary creative director of London Underground who became a judge of the competition in the late 1920s – the British government remained concerned about the parlous state of industrial design. To alleviate such worries, they established the Gorrell Committee in 1932 as a means to investigate and to plan the exhibition 'British Art in Industry'.

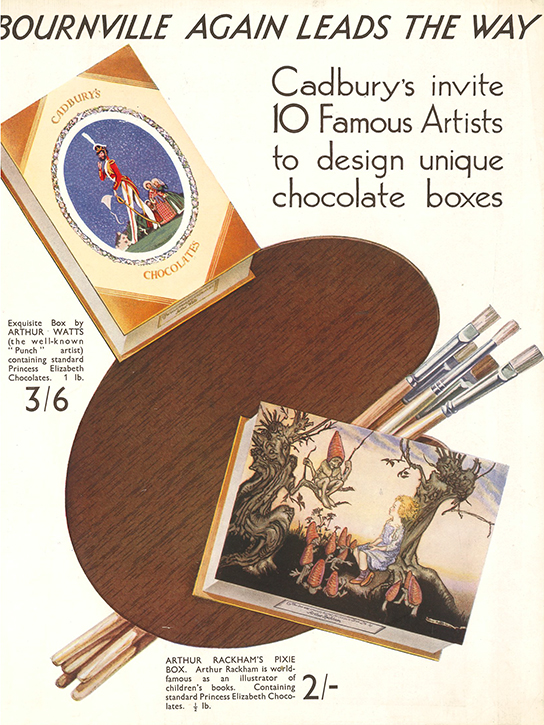

Artist Paul Nash lamented that 'we have not even the sense to recognise the artist's relation to industry', to which Cadbury responded by launching the Famous Artists series of chocolate boxes in 1933. The company offered £1,000 per annum to 'artists and designers who have had no previous experience of our particular industry.' The winners exhibited their designs at London's Leicester Galleries.

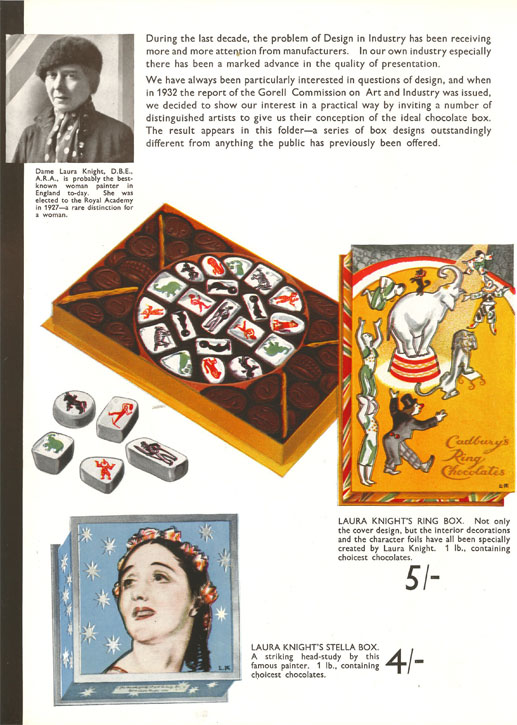

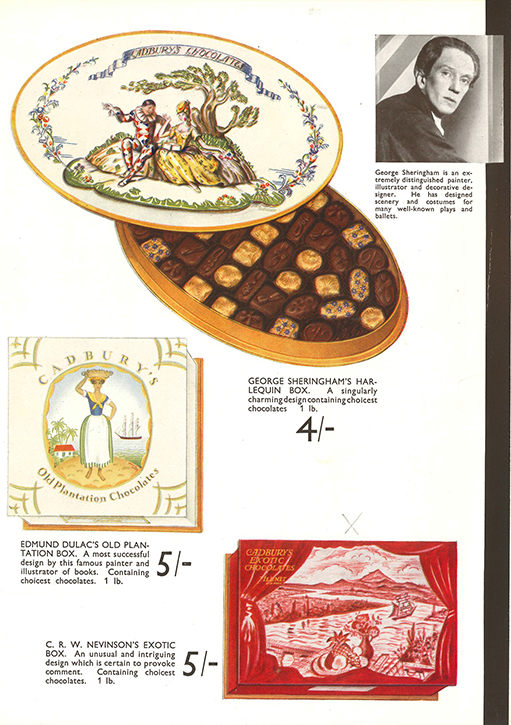

In total, eleven designs were chosen, with one by Paul Nash, ironically, being rejected. Two were by Laura Knight and the rest by Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, C. R. W. Nevinson, Mark Gertler, Philip Connard, Dod Procter, Ernest Procter, George Sheringham and Arthur Watts. To accompany the event, a colourful, printed brochure with studio portraits of the artists was issued.

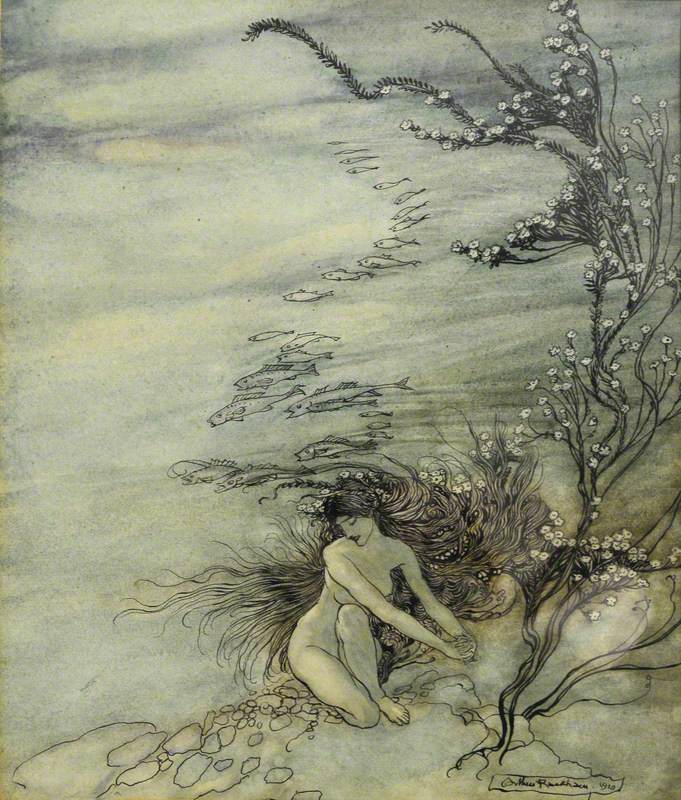

Arthur Rackham (1867–1939) drew inspiration from Nordic influences and Japanese woodblock prints when creating his distinctive pen, ink and wash artworks.

Page from the brochure produced by Cadbury's to promote the 'Famous Artists' range of chocolate box

Famed for his illustrations of children's books such as The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm and Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, his pale landscapes are populated with fantastical creatures like the toadstool pixies on his chocolate box and his trees are embodied with a sinister life of their own.

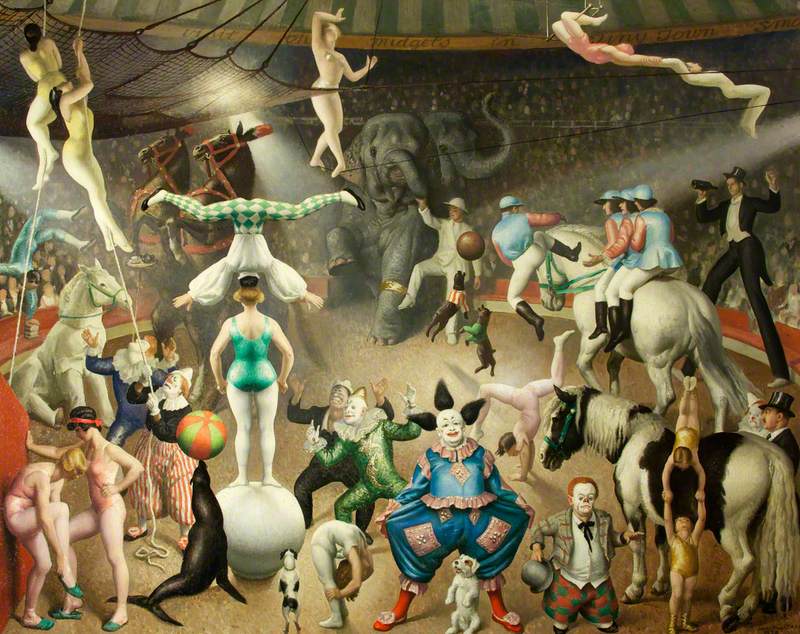

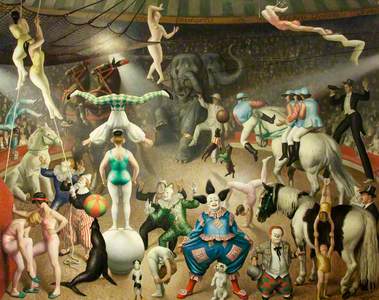

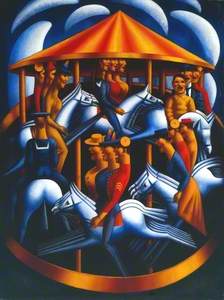

Laura Knight (1877–1970) designed not only a cheerful circus ring for her box but also the individual wrappers featuring performers from the Big Top circus.

Already a star artist and an Associate Member of the Royal Academy, Knight had a fascination with performers and fairs. She had spent a year travelling with the circus, experiencing a life very different from her own. She later reflected:

'I was as much a part of the circus as anyone in the show, used to putting up with anything… the circus itself never lost its fascination, the multitudinous interest and constant change, the endeavour to accomplish the impossible.'

Many of the characters in The Grand Parade; Charivari prefigure those on Knight's chocolate box. The trumpeting elephants and little jacketed dogs leaping to perform tricks with a ball, the balancing acrobats and clowns striking poses all have counterparts in the Cadbury's design.

The word 'charivari' means a discordant noise or din, and this painting resonates with an imagined cacophony.

Laura Knight's page in the brochure produced by Cadbury's to promote the 'Famous Artists'

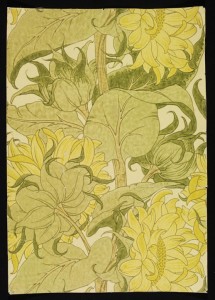

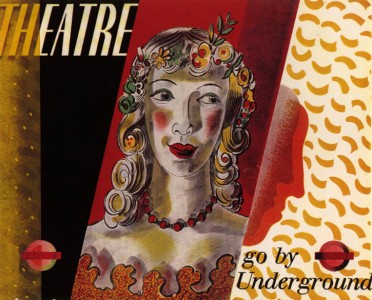

George Sheringham (1884–1937), who trained at the Slade, intended to become a portrait painter or watercolourist, but eventually turned to decorative art, costume and theatre design.

'Midsummer Madness'

(design for the stage setting of Clifford Bax's opera) 1924

George Sheringham (1884–1937)

Inspired by Oriental art and the aesthetic of the Ballets Russes, as well as Jean-Antoine Watteau's pastorals and the commedia dell'arte, he created the decorative scheme for Claridge's ballroom and designed four Gilbert and Sullivan operas for the D'Oyly Carte.

A 1910 exhibition showing designs for fans and silk panels earned him many admirers, with his fan designs often purchased as artworks.

On his chocolate box, a harlequin pays court to a lady in a crinoline. Could that box on her lap symbolise the gifting of a Cadbury's assortment?

Page in the brochure produced by Cadbury's to promote the 'Famous Artists'

Including designs by George Sheringham, Edmund Dulac and C. R. W. Nevinson

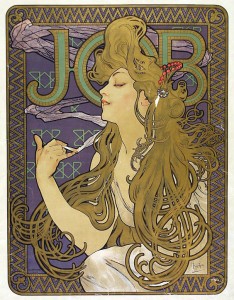

The French-born artist, Edmund Dulac (1882–1953), Rackham's greatest rival, was a prolific illustrator of storybooks. His trademark eastern-influenced style led him towards colourism, as is evident in this beautifully rich portrait of Elizabeth Allhusen.

The subject, wearing a loose 'aesthetic' dress, sits on a chair of upholstered Chinese silk draped with a paisley shawl. Behind her, the gold lacquered panelling and wall-hanging reference the style of Japanese interiors.

Dulac chose a conventional exoticism for his chocolate box design, somewhat disappointing his sponsors. Notoriously perfectionist, he complained that 'the face has been over-engraved... [it] should have been left alone. I don't suppose it can be improved now.'

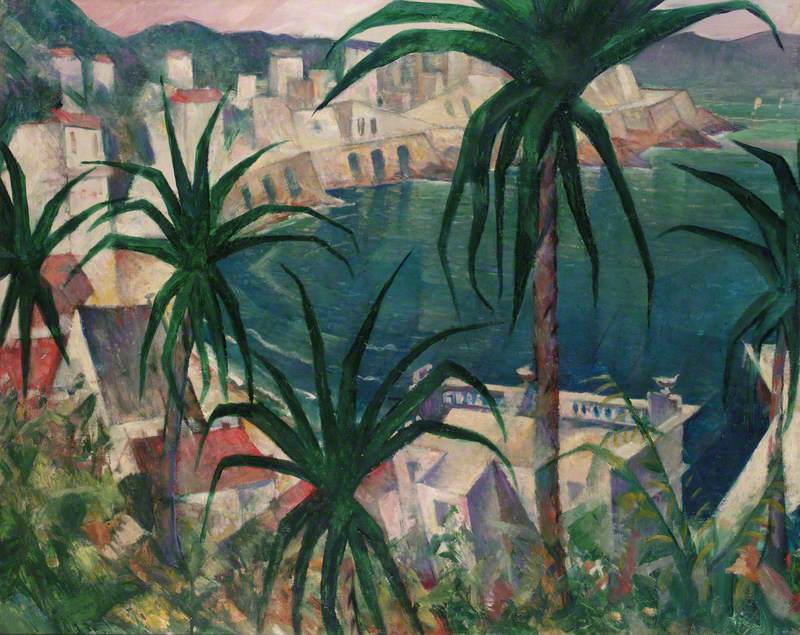

C. R. W. Nevinson (1889–1946), best known as a war artist, turned to gentler subjects in peacetime.

Originally influenced by the avant-garde movements of Vorticism and Futurism, he later took a greater interest in landscapes. His exotic chocolate box scene represents a significant departure in style, however the device of framing the view through heavy curtains was previously employed in his painting A Studio in Montparnasse, while the sweeping bay owes a debt to his slightly earlier work La Corniche.

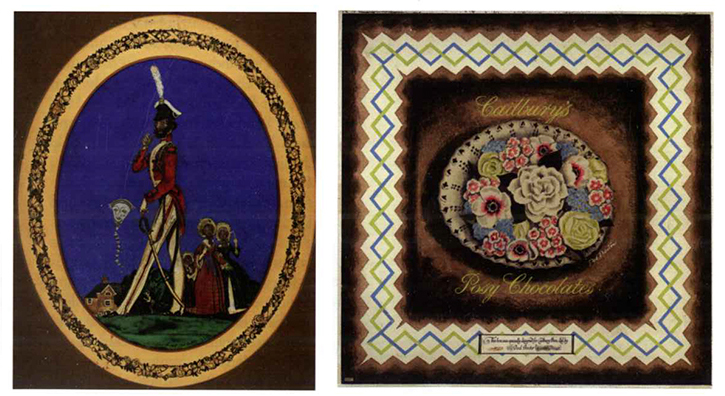

Arthur Watts (1883–1935) trained at the Slade, but was best known as an illustrator and cartoonist for Punch. He designed a number of posters for London Underground and illustrated E. M. Delafield's comic masterpiece Diary of a Provincial Lady (1930).

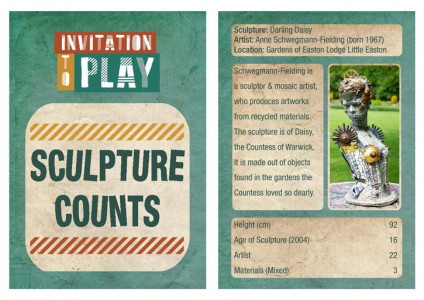

'Exquisite' by Arthur Watts (left) and the 'Posy' design by Dod Procter (right)

1930s, chocolate box designs

The entertainingly vain regimental soldier of his chocolate box seems more than happy to take in the admiring glances of the coy group of women in the background.

Watts had admitted to finding the commission challenging, writing 'chocolate box designing is a more difficult job than I thought'.

A contemporary of Laura Knight's at the Newlyn artists' colony in Cornwall, Dod Procter (1892–1972) was another rare example of a female Royal Academician. After the success of Morning at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1927, when the painting was snapped up by the Daily Mail for the nation, Procter's fame sky-rocketed.

Widely travelled, Procter took inspiration from the people she met and from nature in many forms, especially flowers. Her posy box design demonstrates a botanical accuracy distilled into a simple and stylised arrangement.

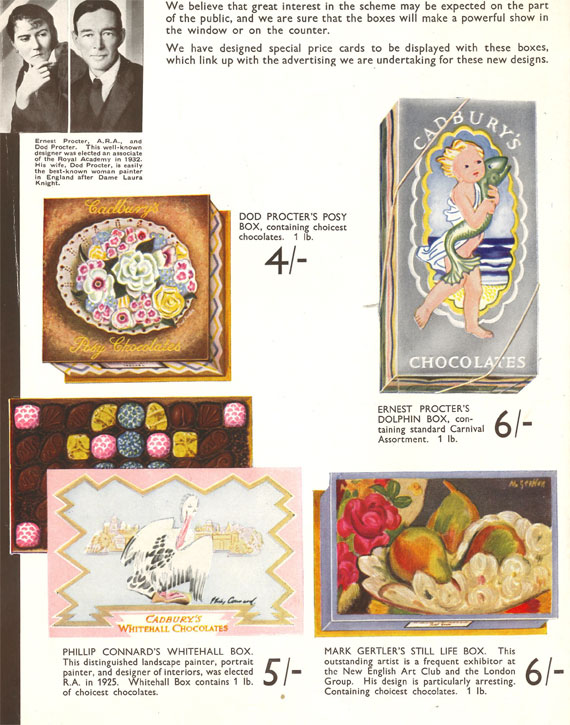

Ernest and Dod Procter's page in the brochure produced by Cadbury's to promote the 'Famous Artists'

The Hall Table reveals her flower painting taken to a masterful level of texture, line and colour. The soft fleshy heads of the informal bunch of tulips spilling out of crisp tissue paper contrast with the softness of the discarded kid gloves and bag, whilst the open box of cigarettes conveys an element of intrigue.

Although critic James Laver condescendingly suggested that no Royal Academician was known for painting flowers, Dod went on to become better known than her fellow RA and husband Ernest.

Ernest Procter (1886–1935), a painter of portraits, landscapes and still lifes, like Dod took on commercial work including designs for the potter and ceramicist Clarice Cliff. For his chocolate box, he turned to the mythological and his little sea sprite, expertly clutching a rather uncomfortable-looking dolphin to its chest, finds a parallel in the Gemini of his lively work The Zodiac.

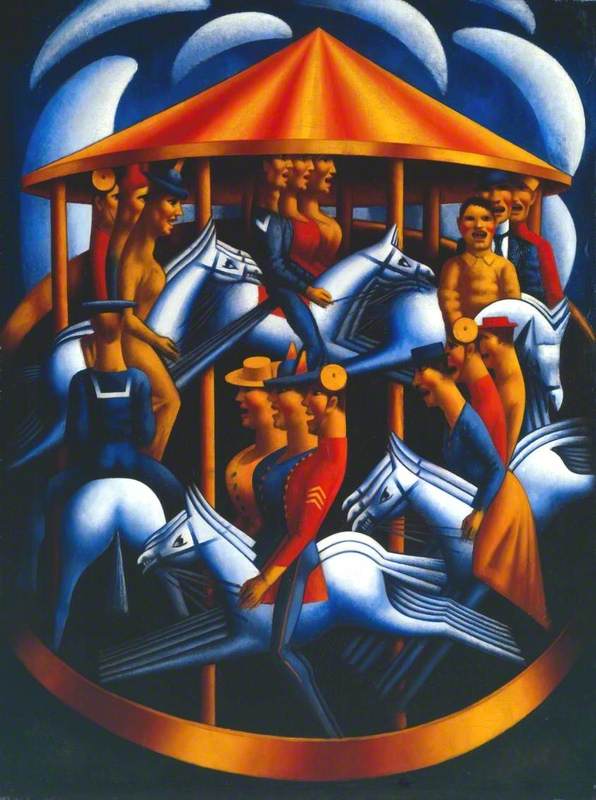

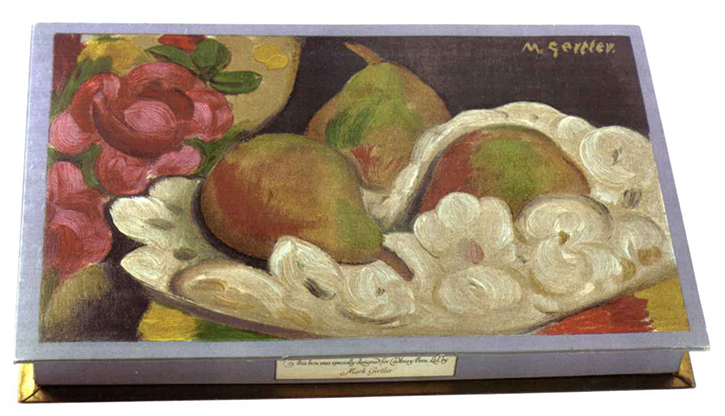

Referred to as an 'outstanding artist' in Cadbury's brochure, Mark Gertler (1891–1939), was the son of Polish Jews living in Whitechapel who gained financial assistance to study at the Slade.

It is hard to imagine the artist of the disturbing Merry-Go-Round being approached for confectionery design, but Gertler frequently depicted flowers and fruit in his still lifes.

Still Life

1930s, chocolate box design by Mark Gertler (1891–1939)

The rich, jewel-bright colours he typically used in these works are echoed in his box design. No stranger to commercial art, he also produced luscious fruit paintings for a series of seasonal Empire Marketing Board posters in 1931.

'Whitehall', with notes

1930s, chocolate box design by Philip Connard (1875–1958)

The pelicans of Lancashire-born Philip Connard's (1875–1958) 'Whitehall' box were the fruit of much meticulous sketching at London Zoo and find an antecedent in his Pelican Ponds painting of 1930 and a London Transport poster The Pelicans of Whitehall. Known primarily at this period for his romantic and decorative landscapes, Connard painted views of the Thames from his riverside home in Richmond. These swans, preening their feathers like their more exotic cousins, may well have resided there.

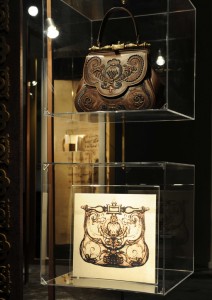

Although the range sadly failed to prove successful for Cadbury's, the lidded gift boxes might well have been kept and used to store items like buttons or memorabilia.

So if you check your grandparents' cupboards, and find an heirloom Cadbury's Famous Artists box, keep it safe. Remember you're holding onto a valuable piece of design history.

Lucy Ellis