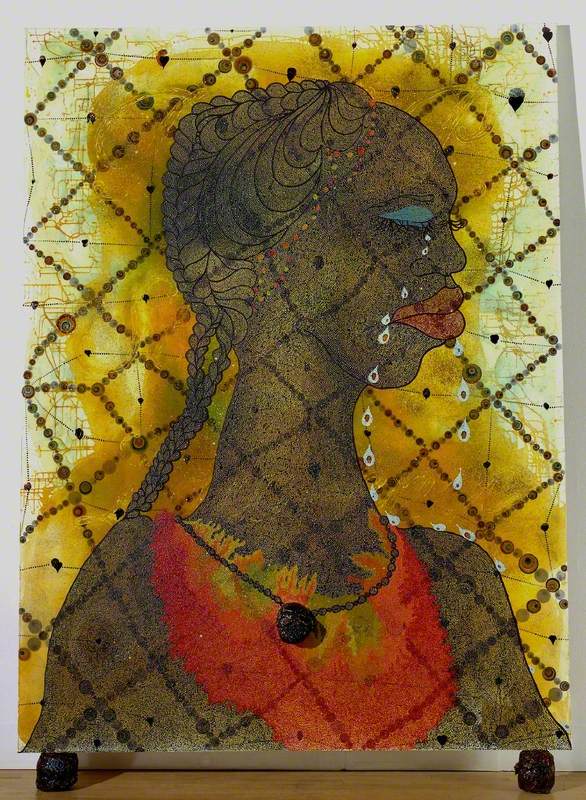

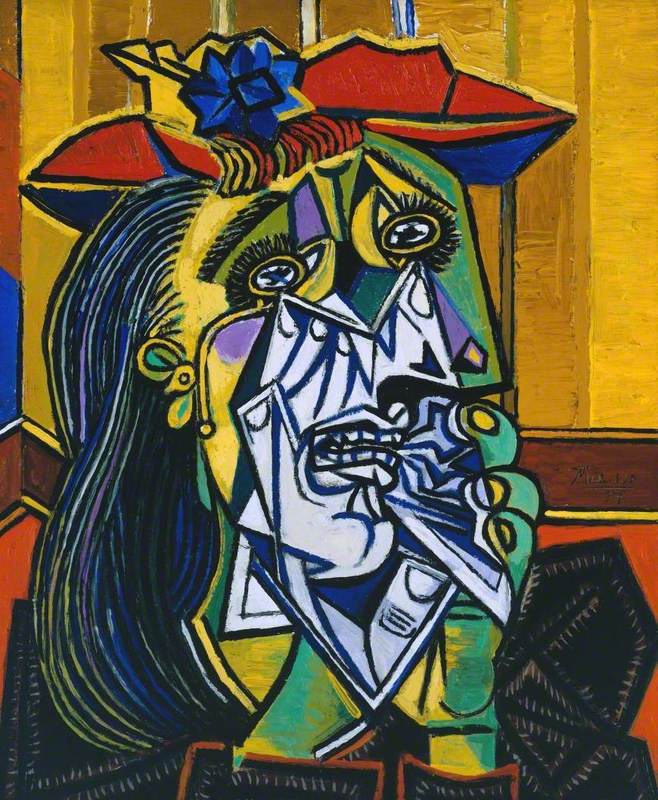

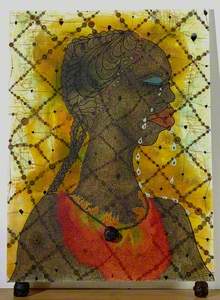

Every one of us, at some time or other, has cried. Yet crying rarely appears in the canon of art history. There are a handful of exceptions, these include No Woman No Cry (1998) by Chris Ofili, Weeping Woman (1937) by Pablo Picasso, and two paintings by Roy Lichtenstein, both titled Crying Girl (1963 and 1964).

Another notable painting which shows a woman crying is Francesca da Rimini by Ary Scheffer. Scheffer is known to have painted six versions of this work, each almost identical to the other. One of these can be found in London's Wallace Collection and was painted in 1835.

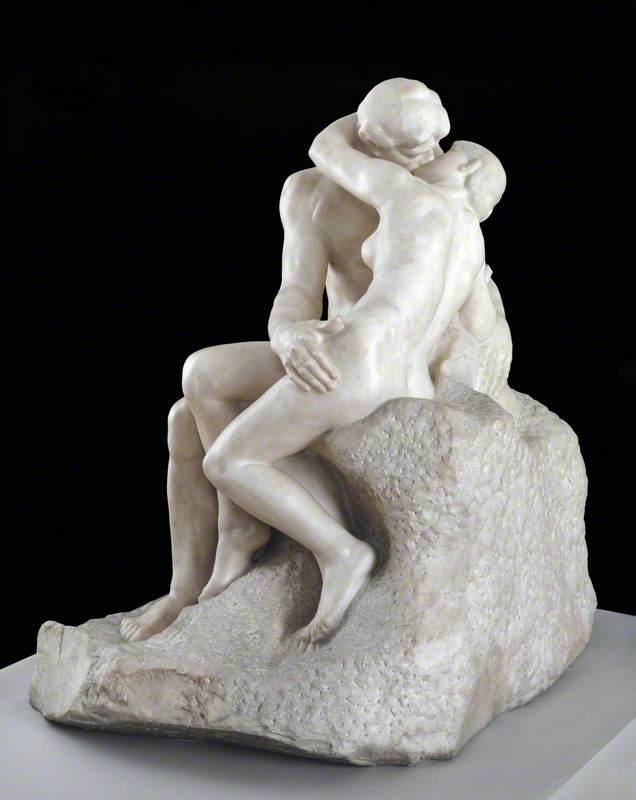

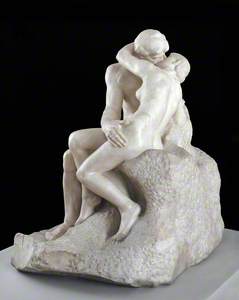

Little is known about Francesca da Rimini. We know she was born in Italy sometime between 1255 and 1260. And we also know she grew up in the Castle of Polenta, in the Province of Ravenna. Yet despite no contemporary portraits of Francesca existing, she has inspired many works of art over the centuries. Perhaps the most famous of these is the sculpture The Kiss of 1882, by Auguste Rodin, which depicts her naked in the arms of her lover Paolo.

While Francesca was growing up, the Provence of Ravenna was subjected to many battles, primarily between her own family in the north, and the Malatesta family to the south. Then in 1275, when she was around 15 years old, her father Guido was elected by Pope Gregory X to rule over the region. That same year, Guido orchestrated a marriage between his daughter Francesca and the eldest son of the Malatesta family, Giovanni. It would appear this was arranged in the hope of uniting the region in peace.

A few decades later, the poet Boccaccio described the events which followed. Boccaccio claims that Francesca was the victim of a deception. Giovanni's nickname was Gianciotto (or 'Crippled John'), due to his disfigured appearance, and because of this, the Malatesta family sent their younger son, Paolo, to sign the marriage contract in his place. Paolo was known as 'the Fair', due to his good looks, and when the marriage was signed he was the one who escorted Francesca to Gradara Castle in the south. This was to be her new home. It was only the morning after arriving at the castle, that Francesca discovered the truth. She was really married to Paolo's older brother, and not Paolo as she had been led to believe.

Although Paolo had conspired to trick her into marriage with Giovanni, he and Francesca fell in love and began an affair. Paolo, like the newlywed Francesca, was also married. Yet they kept their relationship a secret from their respective partners for many years, until one fateful day, around 1283–1284, when Giovanni surprised Paolo and Francesca. Legend holds that they were reading the story of Sir Lancelot in Francesca's bedroom when they were discovered. There and then, Giovanni murdered them both.

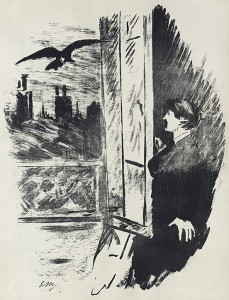

Paolo and Francesca

c.1814–c.1820

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867)

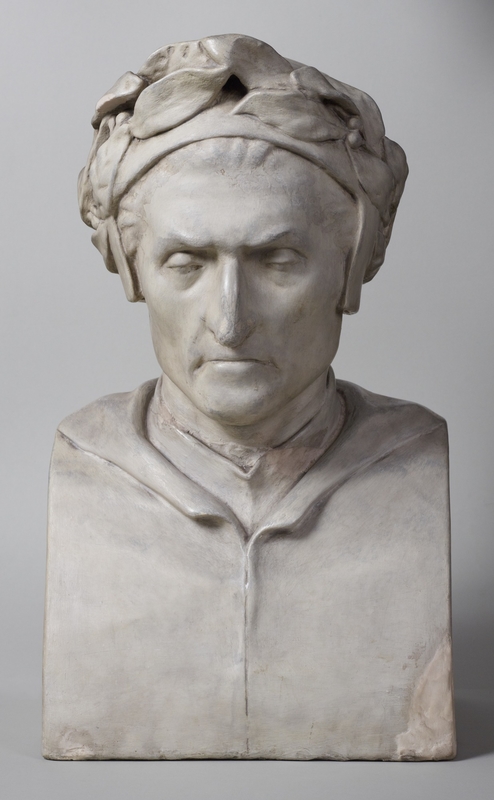

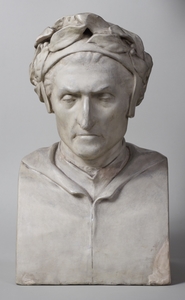

This story was first made famous by Dante Alighieri, who wrote about it in his epic poem The Divine Comedy, completed some 37 years later. Dante had been a contemporary of Francesca's, being around 20 years old at the time of her murder. He was also a close friend of Francesca's nephew, Guido Novello da Polenta. Indeed it was Guido who gave Dante a home in the city of Ravenna from 1318–1321 after he had been exiled from Florence. These were to be the final years of Dante's life and it was here that he completed The Divine Comedy.

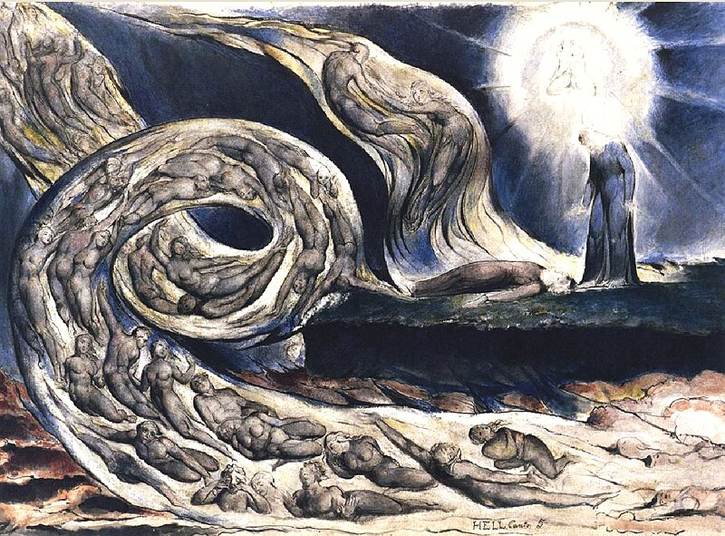

As a story, The Divine Comedy tells of the fictitious 'Dante the Pilgrim' who is escorted through the nine circles of Hell by the ghost of the poet Virgil. It is in the second circle of Hell, which is reserved for the souls of the lustful, that Dante and Virgil meet Paolo and Francesca. Here, the lovers are trapped forever by an eternal whirlwind; a metaphor for how they themselves had been swept away by their passions.

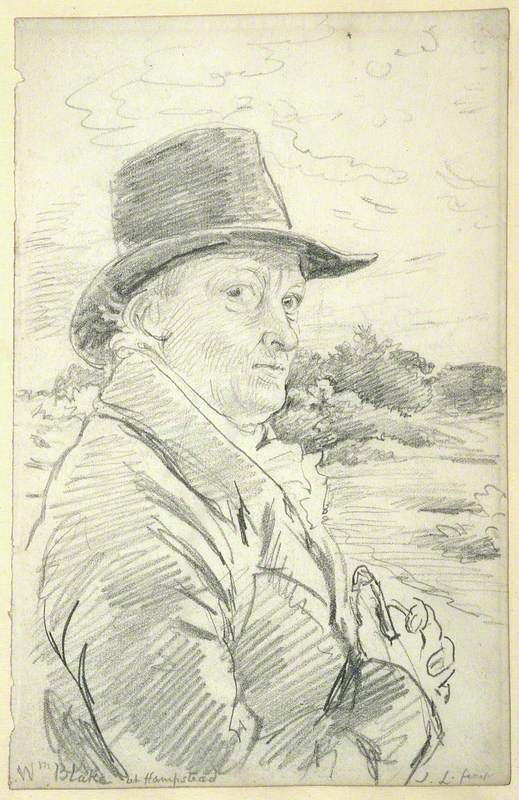

The Lovers' Whirlwind, Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta

1824–1827, pen, ink & watercolor on paper by William Blake (1757–1827)

Dante and Virgil pause and summon Paolo and Francesca to speak with them. Paolo remains silent and weeps, while Francesca recalls their story. In the telling, she does not refer to Paolo by name, referring to him only as 'this one'. She describes how Paolo first fell in love with her body, and that by return, this love seized her too. And how they held no control over this feeling, which ultimately led to their murder and eternal torment in the underworld. On hearing her story, Dante the Pilgrim says that her fate has brought tears of pity to his own eyes. It is this moment that Ary Scheffer captures in his painting.

In Scheffer's painting, we see Francesca and her lover wrapped in each other's arms, trapped in hell, naked except for a white shroud, which partially covers them. They are to be forever swept through the air, just as they had allowed themselves to be swept away by passion. Standing in the shadows to their right are Dante and Virgil, contemplating their fate. On Paolo's exposed chest we notice a small cut, and another of a similar size in Francesca's left shoulder. From this we can surmise Giovanni killed them simultaneously with a sword, while they were lost in a passionate embrace. Paolo's left arm covers his face. At first glance, it is hard to detect, but when we move in closely we see a tear flowing from Francesca's left eye.

In his painting, Scheffer has altered the original story. For where Dante only tells of himself and Paolo weeping, in Scheffer's depiction, now only the woman cries. Why though, would Scheffer wish to place a tear in the eye of Francesca when none is mentioned by Dante?

We notice something similar happening in Pablo Picasso's 1937 painting Weeping Woman in the Tate collection. This is a small painting, measuring 60 x 49 cm and shows the face of Dora Maar, Picasso's then-lover and muse.

Picasso depicts Dora's face fractured like broken glass which appears to express a sense of her subconscious spilling uncontrollably into the outside world. He partly achieves this by drawing on his cubist technique to present the subject. His use of saturated colour, another cubist approach, amplifies tension across the canvas. This is further enhanced by the small central area below Dora's eyes, which appears in monochrome. This central motif appears shaped like a heart and contains Dora Maar's tears. It looks like a handkerchief yet also reveals her mouth, chin and right hand. The contrast between the area of the canvas rendered in black and white and that painted in colour indicates that the monochrome area represents her interior emotional world, while the exterior is shown in colour.

We may view the tears of Dora Maar in Weeping Woman as tears caused by Picasso's abusiveness during their relationship. Yet, Maar once told the US writer James Lord 'All (Picasso's) portraits of me are lies. They're Picasso's. Not one is Dora Maar.'

We see that just as the tear in Francesca's eye is placed there by the hand of Scheffer, so too are those of Maar by Picasso. And while we can only speculate as to why they painted tears in the eyes of women where none had existed, we can explore the meaning they create for us. For these tears are tears of projection.

The tears of sadness appear to come at a moment of letting go, a point at which we reveal the truth of a difficult situation to ourselves. It may be that to manage up to this point, we have lived in denial of a reality we could not face. But the burden of that reality eventually becomes too great to refute, and we become defenceless against it. Yet it is at this moment we become strong. Because it is at this moment we turn to face the difficult truth and allow others into our lives to help.

Many will argue over the nature of truth itself, some saying it is subjective, others objective and a few somewhere in between. Yet truth is one certain thing: it is the rock to which we anchor our feelings. Truth is the opposite of lying. We know lies because they require us to make a conscious decision to construct a falsehood. What we observe, in this context, is that we do not have to consciously adhere to the truth. Truth is a default setting. Truth always guides us to the right action. Truth is often hard and our feelings are deeply affected by it. We cannot control or contain the truths around us. And we cannot control or contain the emotions we experience in relationship to truths. Yet we can do one thing: we can decide how we respond to our emotions.

By painting a tear in the left eye of Francesca, Ary Scheffer created a metaphor for this deeply human experience. In doing so, he turned an illustration of a passage from Dante's Inferno into a work of art. The story Scheffer tells us is that the truth can sometimes be difficult to accept and come to terms with. When it is hard, we might sometimes wish to run away and seek emotional refuge in half-truths and reassuring falsehoods. But when we live a lie, it will eventually cause a crisis. Because a lie is not sustainable.

In responding to our emotions we can choose to steer ourselves to love. If we listen quietly, our instincts tell us how. In choosing love, we place the needs of those around us before our own. Love, even in the face of hardship and sorrow, leads ultimately to happiness and profound peace. The songs, dramas and works of art we create act as vessels for feelings of love. Like tears themselves, they offer us a means to project our internalised emotions externally and help us to understand and navigate our complicated feeling about human existence. In doing so we learn to connect with the people, concepts and places around us.

In the gospel of John 8:32, we read the famous line: 'Then you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.' In Dante's telling of their story, we see how Paolo and Francesca did not own their truth during their lifetime, and it trapped them forever. This was their real tragedy.

Robert Priseman, artist, curator and writer