In 1936, Laura Knight (1877–1970) was the first woman to be elected a full member of the Royal Academy, well over a century after the deaths of its founding female members Mary Moser (1744–1819) and Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807). They had been granted lesser access to the Academy due to their gender – as women, they could not attend life classes or hold office.

Knight, however, was a painter who dismantled institutional gender barriers. She received unprecedented acceptance and success as a woman artist, though she was not exempt from criticism. In 1929, she became the first female artist to be appointed Dame of the British Empire. In the 1940s she was appointed war artist and in 1946, was invited by the War Artists Advisory Committee to paint the Nuremberg Trials, cementing her reputation as an important chronicler of history.

Fifty years since her death, we explore the lesser-known aspects of Knight's diverse practice, highlighting her desire to represent the female gaze and marginalised subjects.

Generally speaking, history has portrayed Knight as an artist of the 'establishment'. Indeed, she deliberately inserted herself into the artistic 'boys' clubs' and became a prominent public figure who wielded considerable influence in artistic circles. In 1965, she became the first female artist to hold a solo retrospective at the RA and was invited to the previously male-only dinners.

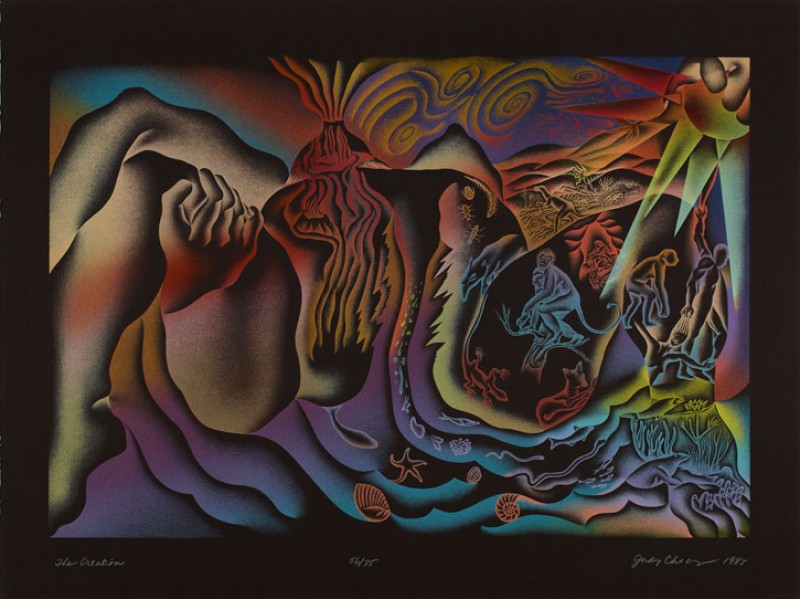

Perhaps in an attempt to be regarded on an equal footing, Knight embraced subject matters popularised by her male peers. She painted the female nude – a rare and bold move for a woman artist at the time. Until the late nineteenth century, it was deemed highly improper for women to attend life drawing classes, and such conservative attitudes persisted well into the twentieth century.

As the feminist art historian Linda Nochlin wrote in her 1971 essay Why have there been no great women artists?, the exclusion of women in life drawing classes ultimately hindered their success, as 'to be deprived of this ultimate stage of training meant, in effect, to be deprived of the possibility of creating major art works.'

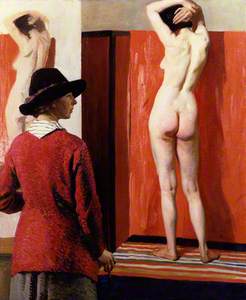

Like her male peers, Knight also pursued the tradition of self-portraiture with a flair of bravado. Works such as 1913's double portrait, Self Portrait aka The Model, demonstrated the artist's ambition. She subverted the traditional 'male gaze' and adopted a radically modern form of female attire and representation. According to Pamela Gerrish Nunn, this particular work made 'it clear that she was capable of that allegedly critical subject, the naked human body, that men liked to discuss at such inexhaustible length.'

Knight was also known for painting ordinary people. Throughout her life, she maintained an interest in social documentary.

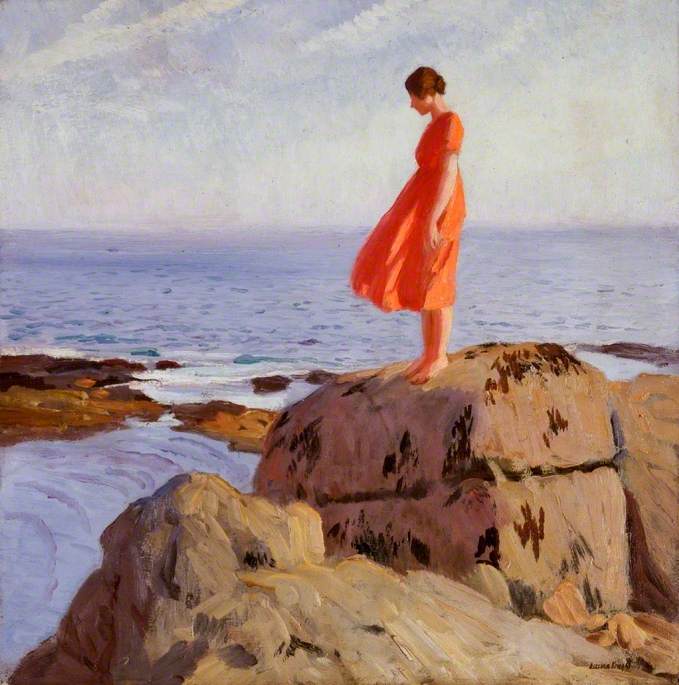

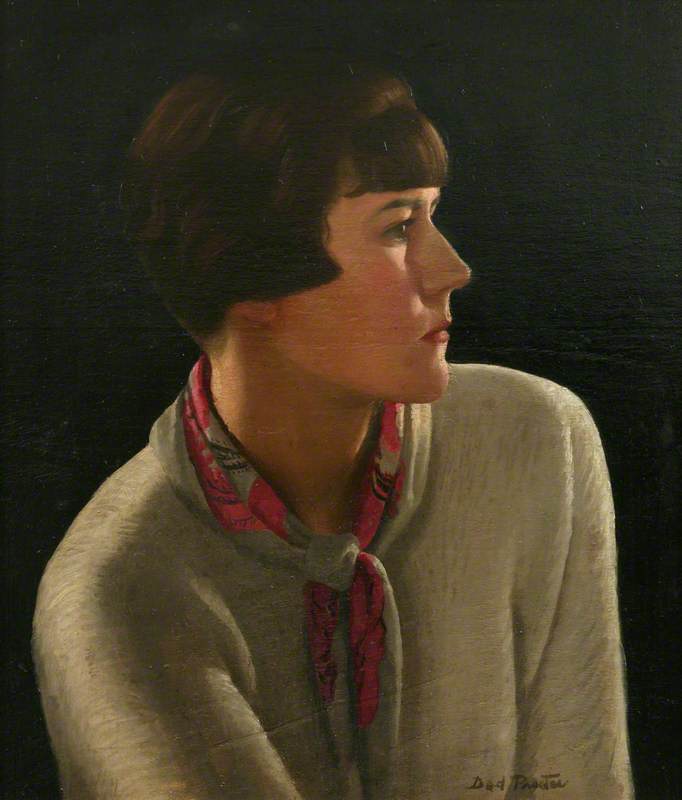

One of her earlier works, The Fishing Fleet, was created only a few years before Knight's marriage to the fellow painter Harold Knight in 1903, who greatly influenced her work. The couple had moved to the artists' colony and fishing village, Staithes in North Yorkshire before eventually settling in Cornwall in 1908 among the influential Newlyn School of artists. Knight had painted his future wife a decade before – the painting is in the Royal Academy's collection under her maiden name of Johnson.

In Staithes, Knight had depicted the inhabitants of the coastal community, capturing the poverty she encountered. These formative experiences would go on to shape Knight's career. She continuously returned to humble subject matters, despite earning lucrative commissions from members of the cosmopolitan elite and even the Royal Family.

In her 1936 autobiography Oil Paint and Grease Paint, she wrote: 'Staithes was too big a subject for an immature student, but working there I developed a visual memory which has stood me in good stead ever since.'

Knight's lifelong concern and interest in the plight of working individuals likely stemmed from her origins as a daughter of a single mother and amateur painter from Nottingham. Born Laura Johnson in 1877, Knight's upbringing was characterised by strife and financial problems, setting her apart from many of the established artists she encountered.

Her formal artistic education was largely down to luck – her mother taught part-time at the Nottingham School of Art and managed to enrol her daughter as a student without paying fees in 1889.

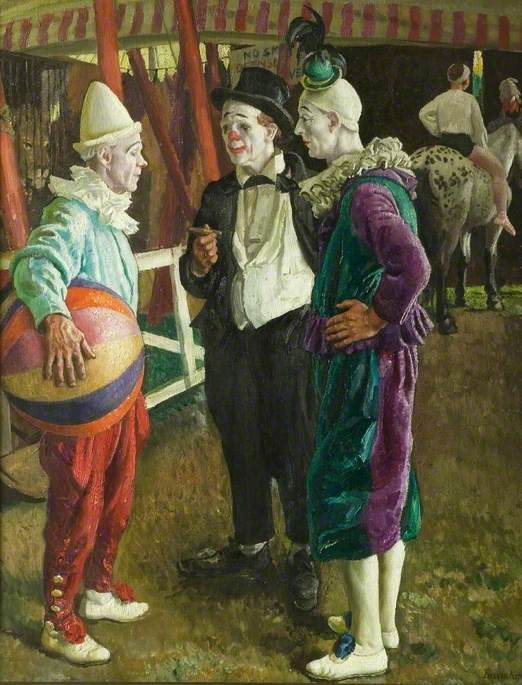

Knight thus had a long-term affinity for the bohemian and creative workers she regularly painted: the circus performers, travelling communities, and ballet dancers.

She often painted the female figures of these groups with gravitas and dignity, elevating their lives through her vivid and commanding paintings. Although stylistically traditional, Knight's subject matters were contextually novel, setting her apart from contemporaries.

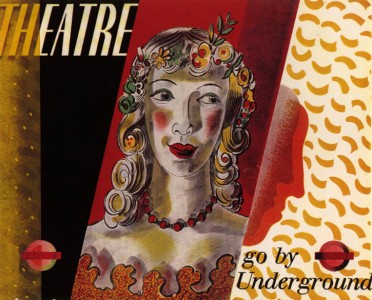

Throughout the late 1910s and 1920s, Knight had regularly painted theatre and ballet productions, including the Sergei Diaghilev's famous Ballet Russes. Though she resided in Cornwall, Knight spent months in London to attend the Empire and Palace Theatres, sketching dancers such as Anna Pavlova and Lydia Lopokova backstage.

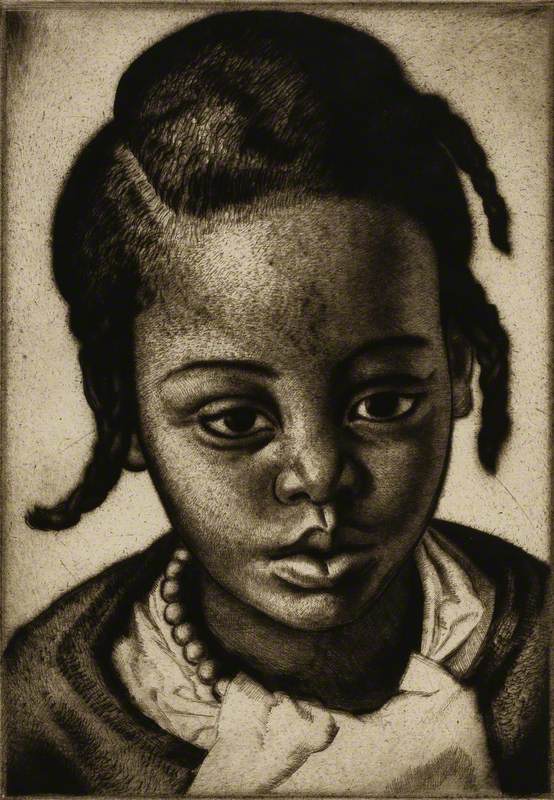

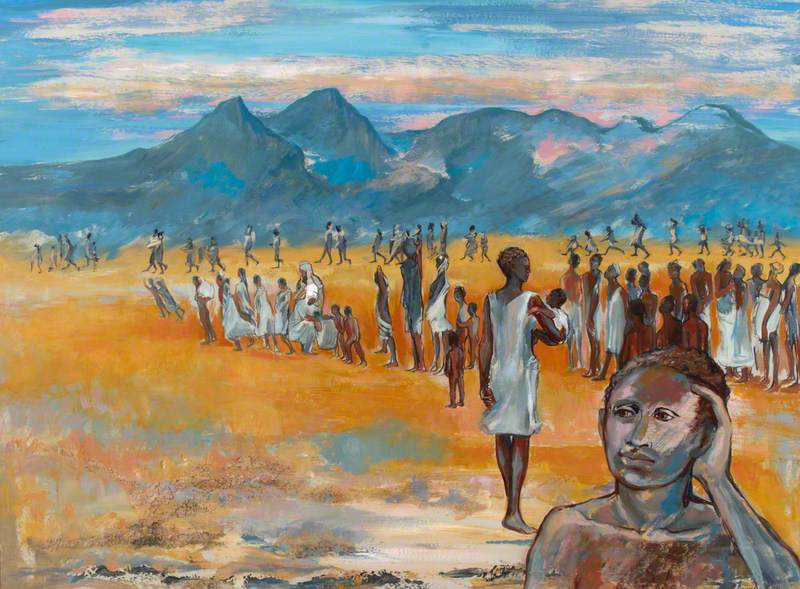

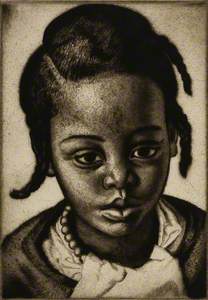

In the late 1920s, Knight travelled to the United States and spent time in Baltimore while her husband completed a commission for the Johns Hopkins Hospital. There, the couple witnessed the effects of Jim Crow laws and racial segregation. At that time, even African American wards in the hospital were segregated from the white civilians.

One of Knight's most astonishing paintings, Madonna of the Cotton Fields (1927) was created during this time and can now be found in the Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, Australia. By imitating the compositional style of a Pietà painting, the work depicts an intimate portrayal of a black mother holding her young toddler.

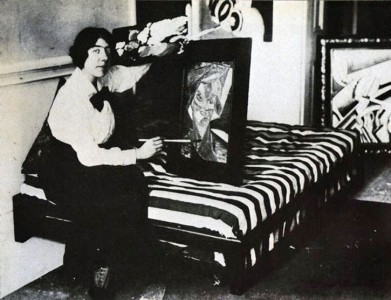

It is not so different from her painting Motherhood (c.1922). In this photograph of Knight in her studio from 1927, the painting can be glimpsed, positioned at her easel.

Laura Knight

1927, bromide print by Press Association Photos

While in Baltimore, Knight painted many black sitters, both male and female, all of whom she depicted with integrity. The artist's sense of warmth and empathy for her sitters is clear.

View this post on Instagram

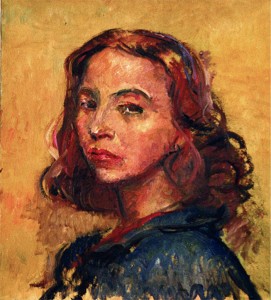

In 1926, Knight painted Study of a Young Woman. Around the same time, she painted Pearl Johnson, a woman who later invited the artist to attend a civil rights meeting.

Pearl Johnson (1926) by Laura Knight, the painter was later taken to a civil rights meeting by the sitter #womensart pic.twitter.com/g8RL3aCjzO

— #WOMENSART (@womensart1) November 26, 2018

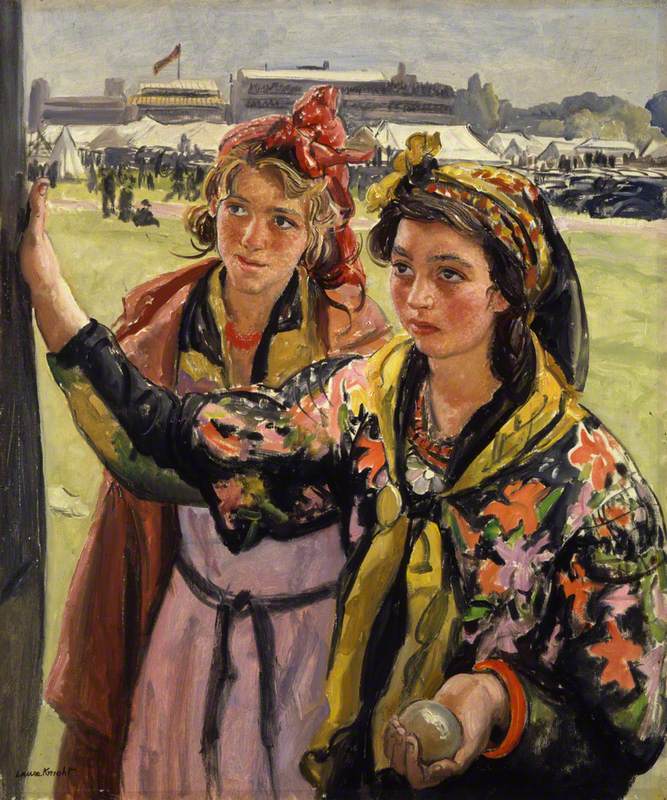

During the 1920s, her interest in the circus – a popular national entertainment at the time – grew and led Knight to immerse herself among the travelling and gypsy/travelling communities in the 1930s.

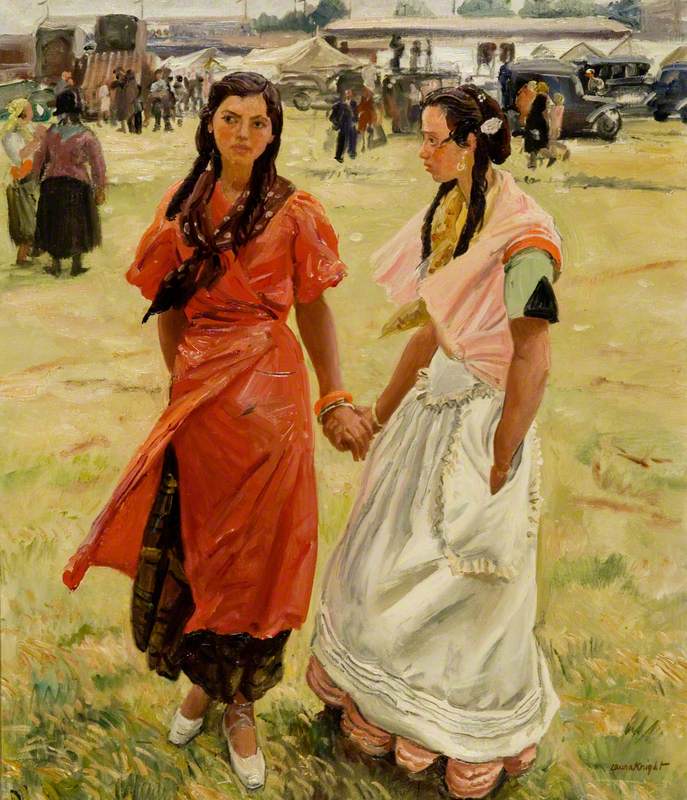

In the late 1930s, Knight spent time living among the nomadic communities in Iver in Buckinghamshire, Ascot in Berkshire, as well as Epsom in Surrey, where it is believed that Romani communities have resided since the sixteenth century.

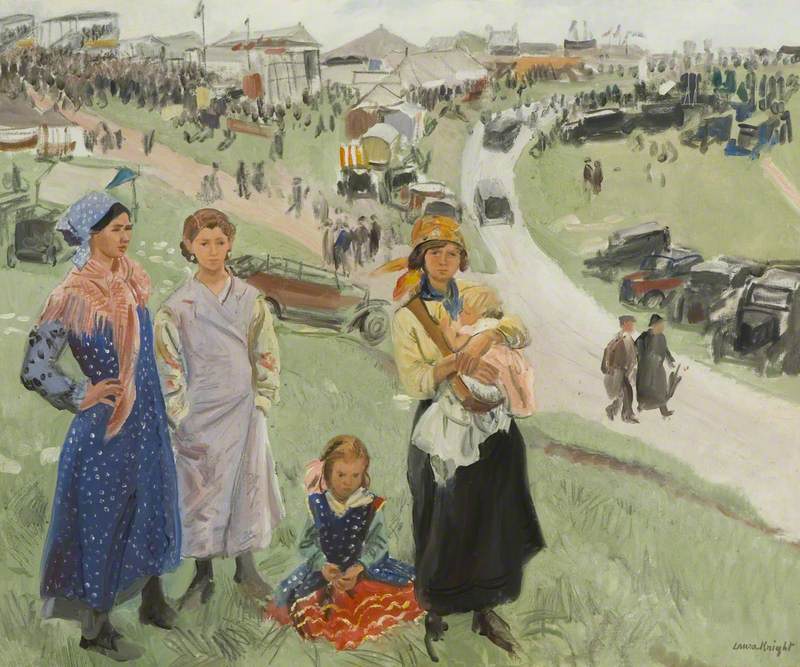

Rather than observing subjects from an impersonal distance, Knight socialised and engaged with her sitters, immersing herself in their way of life. The painting Epsom Downs (c.1938) shows some of the women of these communities who Knight would paint rapidly while balancing her easel in the back of a borrowed Rolls-Royce.

By the 1940s, the War Artists' Advisory Committee contracted Knight as an official war artist. In 1939, she had been commissioned to produce a recruitment poster for the Women's Land Army. From there, she would go on to complete around 17 paintings reflecting women's contributions to the war effort.

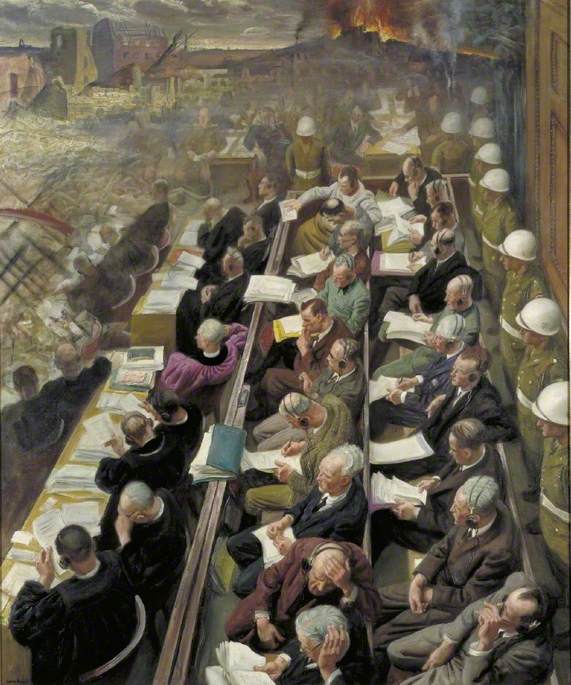

In 1946, the political apex of her career arrived when she spent three months in Germany officially documenting the Nuremberg Trials of the Nazi war criminals.

In the later decades of her life and during the post-war era, Knight returned to her favourite subjects: the circus acrobats and the travelling, Romani communities – groups of people usually neglected and disenfranchised by the mainstream.

Five years before she died, Knight revealed her own feelings about being a woman artist who remained an 'other' in her field, despite arguably shattering the glass ceiling and paving the way for other women. In her 1965 autobiography The Magic of a Line she wrote:

'Even today, a female artist is considered more or less a freak, and may be undervalued or overpraised, and by sole virtue of her rarity and her sex be of better press value... Now that womankind are no longer born to hold a needle in one hand and a scrubbing brush in the other, what great things may not happen?'

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Further reading

Pamela Gerrish Nunn, 'Self-Portrait by Laura Knight' in The British Art Journal, 2007

Linda Nochlin, Why have there been no great women artists?, 1971

Laura Knight, Oil Paint and Grease Paint, 1936

Laura Knight, The Magic of a Line, 1965