When Kyffin Williams (1918–2006) died at the age of 88, his pictures had become so familiar in the art world and in his native Wales, that they were often simply referred to as 'Kyffins'. He became a Royal Academician in 1974 and, at 80, he received a knighthood.

Few artists reach such peaks. What's particularly unusual about Kyffin Williams is that he enjoyed considerable success throughout his lifetime, as evidenced by the acquisition of paintings from his very earliest exhibitions for the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff and Swansea's Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, amongst other public collections. The strength of the work speaks for itself and these early moments of validation act as markers, helping us to understand the path his long career would take.

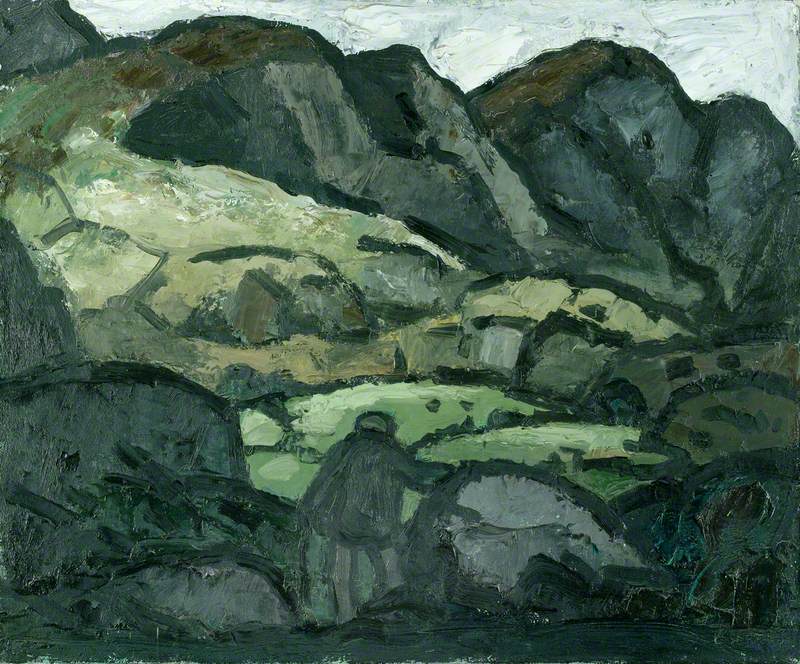

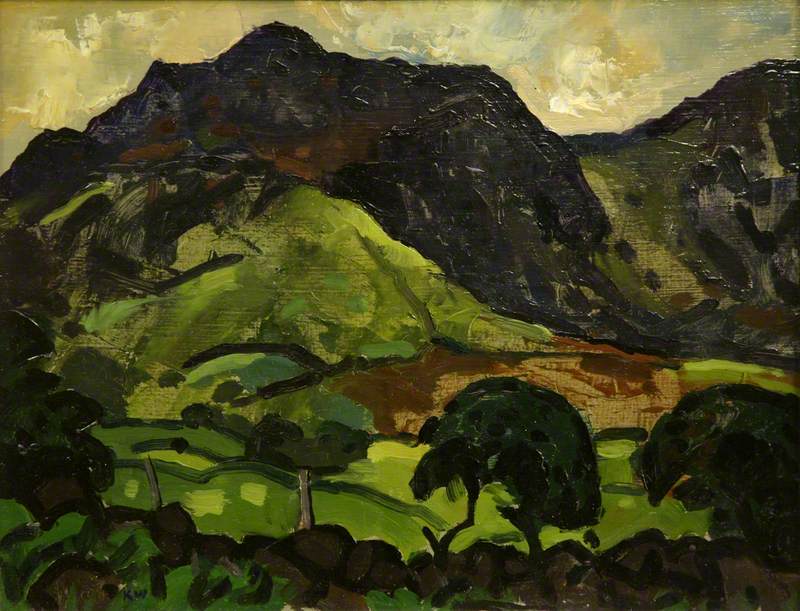

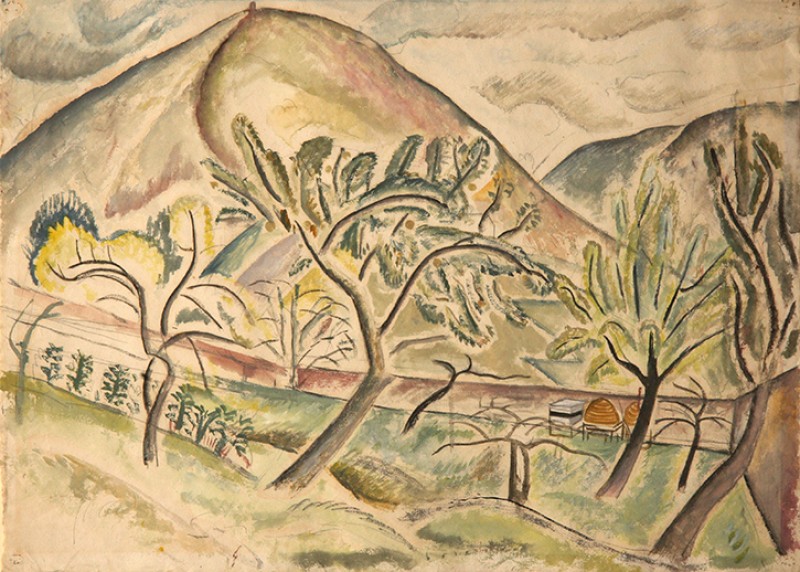

Kyffin's was a boldly expressionist style, already present in works such as Tre’r Ceiri, depicting one of the three summits of Yr Eifl, (also known as 'The Rivals'), on the Llŷn Peninsula in North Wales – the hills of his boyhood. The brilliant greens would later be replaced by the characteristically muted tones of his more widely known Snowdonia mountainscapes, of which the Welsh landscape painter Richard Wilson had also painted two centuries before, and which paved the way for modern landscape painters.

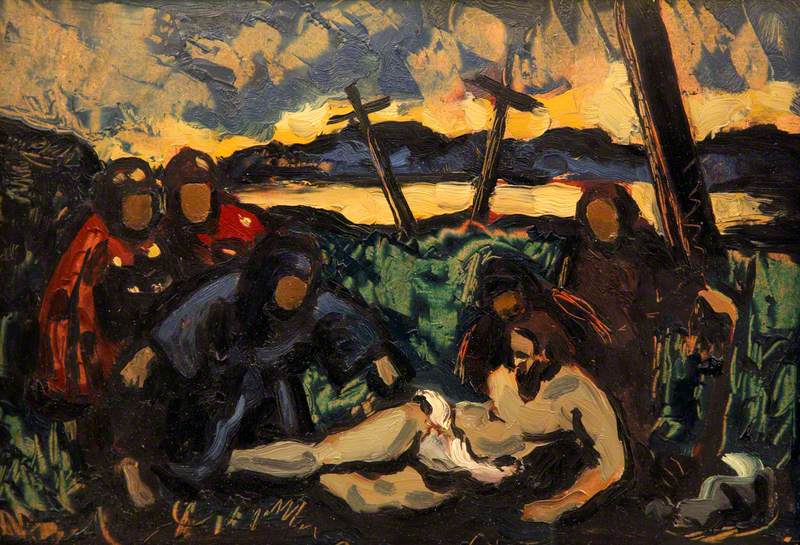

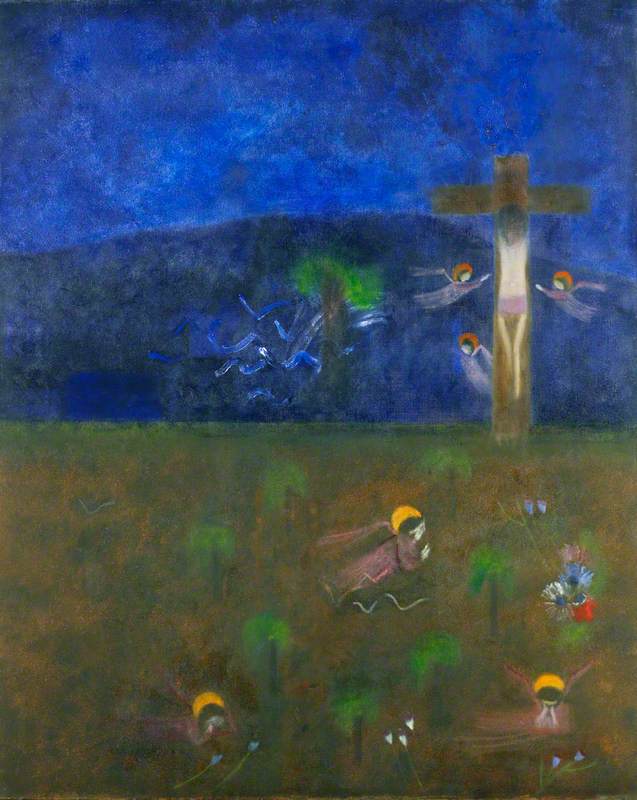

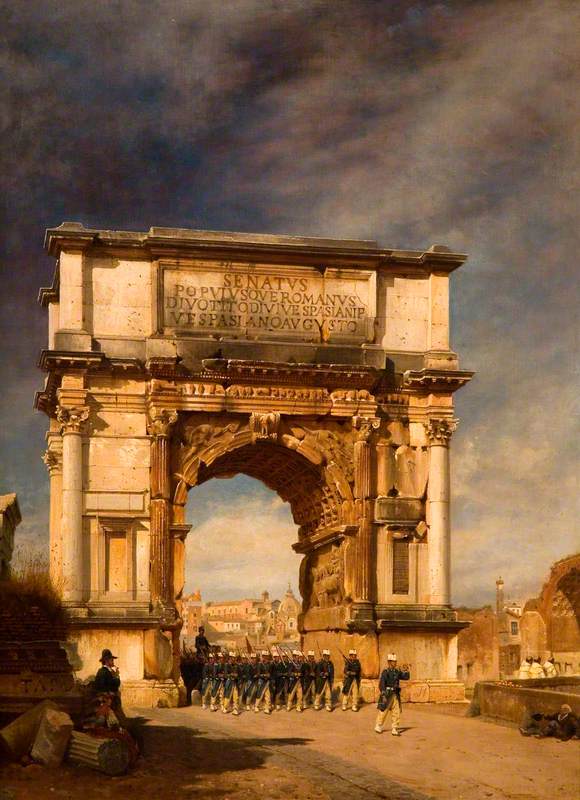

Kyffin, having trained at the Slade School – though based in Oxford during the war years – was determined to extend his artistic apprenticeship, studying and emulating the masters in time-honoured fashion. In this tiny work Deposition, with its bright jewel colours, there is more than a touch of Georges Rouault, whose influence emerges periodically in Kyffin's work over the years.

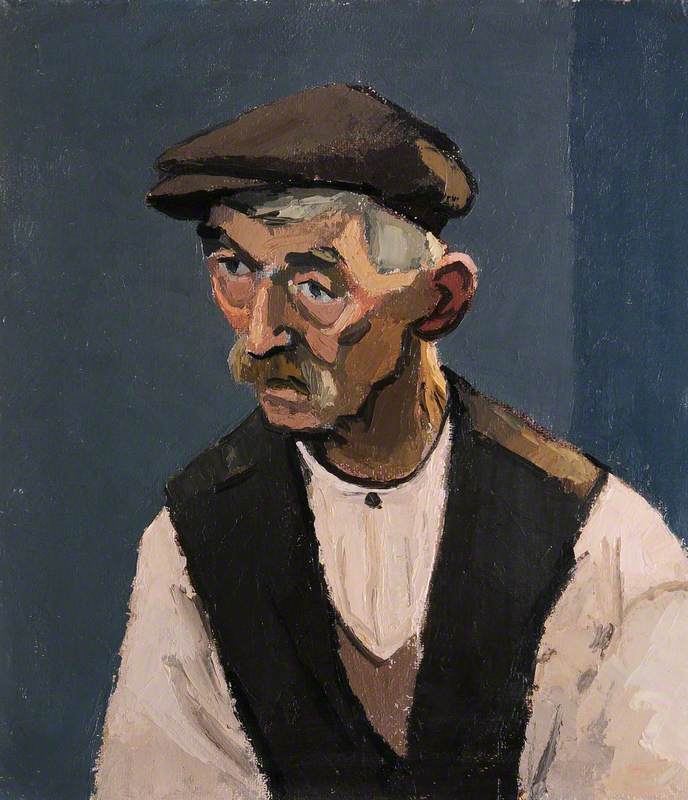

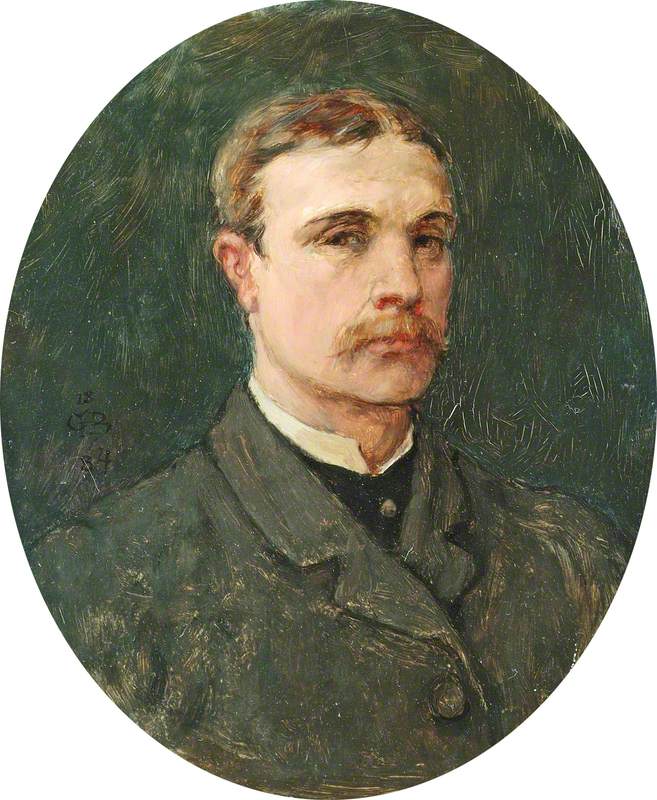

These two pictures were purchased for the Glynn Vivian at Kyffin's first exhibition in the prestigious Colnaghi gallery in London's West End in 1948. Kyffin was not yet 30. The following year, his drawings were shown there alongside works by Augustus John, Muirhead Bone and David Young Cameron. His work also appeared in significant exhibitions at the Leicester Galleries, where this portrait of Hugh Thomas was bought on behalf of the Contemporary Art Society of Wales by Margaret Davies, of Gregynog.

Margaret and her sister Gwendoline had bought paintings by Renoir, Cézanne, Manet, Monet and Van Gogh among others, now part of the National Museum of Wales' collection, and it meant much to Kyffin that Miss Davies also bought his work for herself.

Two further pictures in the Glynn Vivian collection testify to his early command of the medium. In Snowdon from near Harlech, sunlight lends a bright glow to the snow-clad slopes in sharp contrast with those in shadow.

Kyffin talked about loving the clash of the extremes of light and dark, which is reflected clearly in View of Snowdon in Winter (1952), an example of the dramatic mood he liked to create. This painting was seen in the major exhibition of Kyffin's work at the Glynn Vivian in 1953, alongside that of the nineteenth-century landscape artist David Cox. Thirty years later, this picture would feature in the Hayward Gallery's important 1983 show 'Landscape in Britain 1850–1950', the time-boundary stretched slightly by way of accommodation. It was an indication of his place in the canon of British painters.

Kyffin's upbringing, on Anglesey and on the Llŷn, had given him an intimate knowledge of the countryside and its people, in turn dictating his principal subject matter. A genial man but also somewhat of a loner, his passionate identification with both mountains and seashore fuelled the work.

These factors, allied with a natural tenacity, allowed him to pursue his artistic ambition in tandem with – and partly in compensation for – often desperately difficult circumstances since he suffered from epilepsy and, from time to time, depression. Due to an eye condition that made working in bright sunlight uncomfortable he preferred cloudy conditions, explaining why he often adopted a muted palette. The artist himself recognised the element of melancholy in his mountain landscapes, suggesting that stormy seas reflected more turbulent feelings.

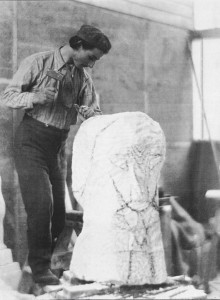

For Kyffin's generation, the stigma of epilepsy was all too prevalent, and it certainly deterred him from marrying. Yet he was more occupied by what he perceived to be the stigma of working with painting-knives. From 1946, when he first recognised 'the palette-knife to be a great ally in expressing the massive bulk of the mountains', Kyffin gradually used brushes less and less, using knives to achieve the thick impasto style, wet on wet, which became his signature. In Britain, prejudice against this technique ran deep, a feeling which lingers today, yet this was never the case in Europe.

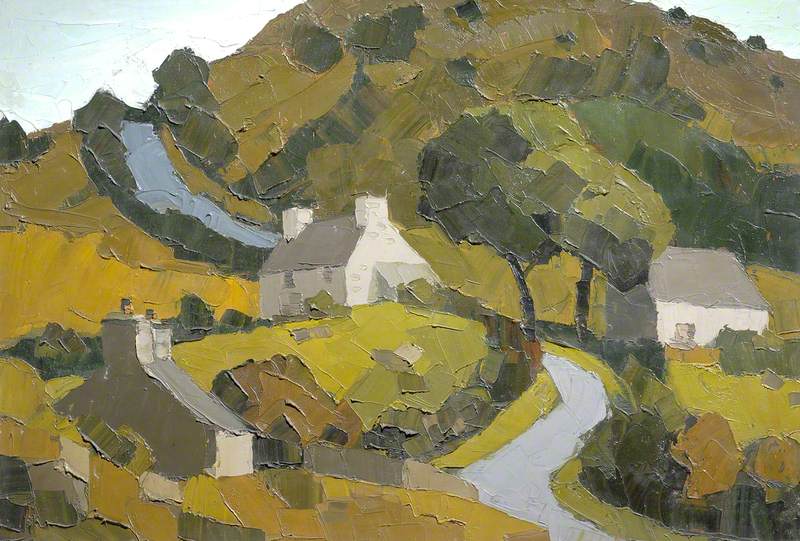

Accordingly, Kyffin sought out the work of artists who'd worked in this way, among them Gustave Courbet, Vincent van Gogh, Chaïm Soutine, and the Russian-French Nicolas de Staël, whom Kyffin was proud to have met on the occasion of de Staël's Matthiesen exhibition in 1952. The latter's use of what he called 'truelles' (painting-trowels), as well as his fast and dynamic approach to working on canvases, offer a direct parallel to Kyffin's methods. De Staël's influence on Williams is legible initially on a small scale, as seen in the rendering of this cottage wall in The Church and Cottages, Aberffraw, but also more broadly. Meanwhile, Kyffin's affinity with Van Gogh, not least because of the shared mental afflictions, is the one he most readily acknowledged.

Although most of Kyffin's output locates him firmly in North Wales, he had (for financial security) combined his art with teaching. For almost 30 years, he was senior art master at Highgate School, juggling three days of classes per week and painting in his spare time and during holidays. That two of his pupils, Anthony Green and Patrick Procktor, went on to be Academicians is proof enough of his impact and inspired approach.

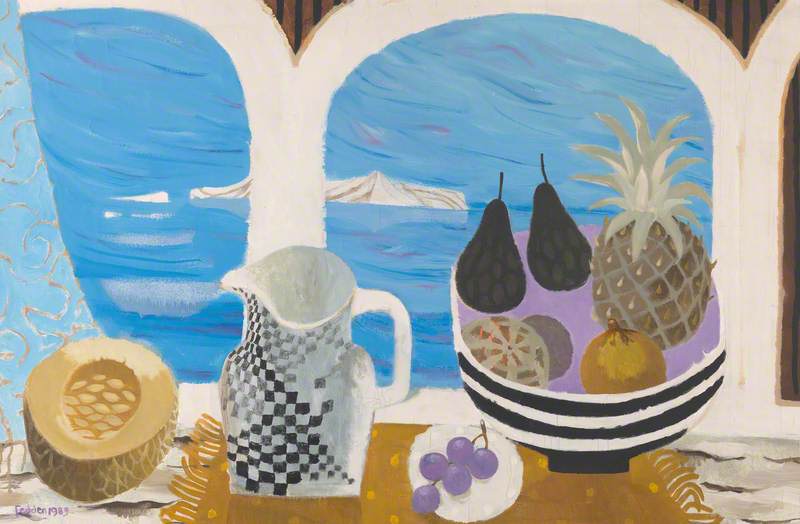

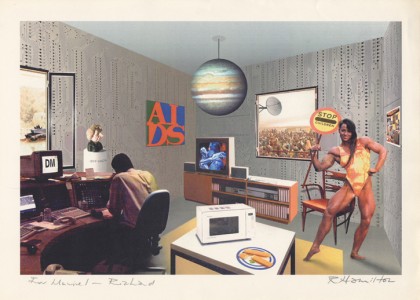

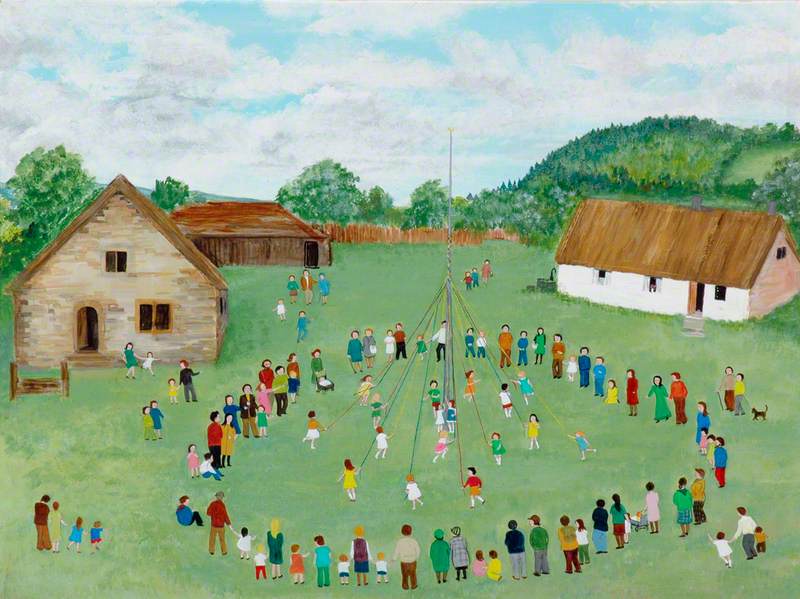

A sabbatical from Highgate would prove to be a landmark in his life and he was awarded a Winston Churchill Memorial Trust fellowship, which allowed Kyffin to visit the Welsh territory in Patagonia in October 1968. Whilst there, he recorded the landscape and life in the Welsh colony that had first emerged in the nineteenth century.

In Patagonia, he drew in pencil and in pen and ink, though he also worked in watercolour before returning to London in the spring of 1969. His oil paintings were the vibrant realisation of his impressions of the landscape and its colours. In 1971, the resulting work was shown in two exhibitions – drawings at Colnaghi's and paintings at the Leicester. The works exhibited were apparently instrumental in Kyffin's nomination as an Associate Member of the Royal Academy.

To Kyffin's satisfaction, since he believed it to be his best painting, Dyffryn Camwy, was bought by the National Museum of Wales. Today, it still remains one of the most stunning examples of his work; evocative of his mood, its surface demonstrates his virtuosic, almost sculptural, use of paint, which shifts from craggy to smooth upwards through the picture. It also shows another facet of Kyffin's art, where a painting will be a realistic representation in geographical, geological and atmospheric terms, yet have parts of the work which read as abstraction. This creation of internal tensions and resolution – combined with considerations of structure and proportion – was always part of his process, and almost unconsciously undertaken.

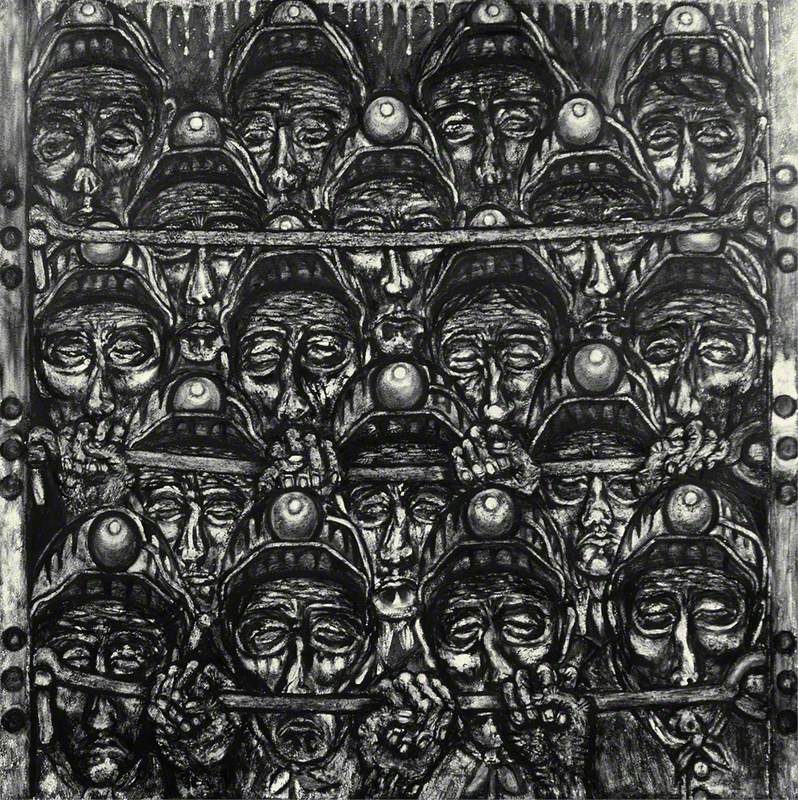

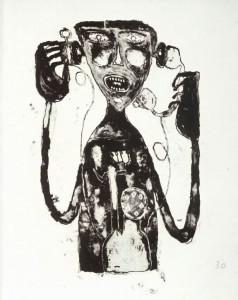

The Patagonia experience also confirmed in Kyffin his commitment to returning to Wales to live and paint full-time. The dramatic contours of Blaen Ffrancon are accurately recorded, with a sombre drama implicit in the balance between mountain and sky, but the paint also carries its own dramatic narrative. The flowing lines and bold gestures of Kyffin's style are found across the genres, his pen and ink drawings, in particular, have the sharp presence of the Die Brücke artists he much admired. But one of the most intriguing aspects of his work is his portraiture.

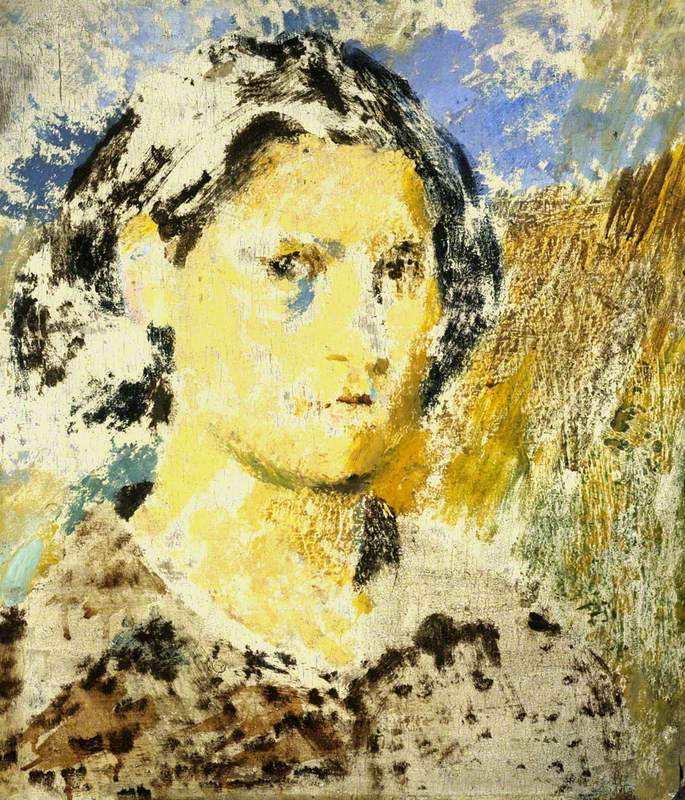

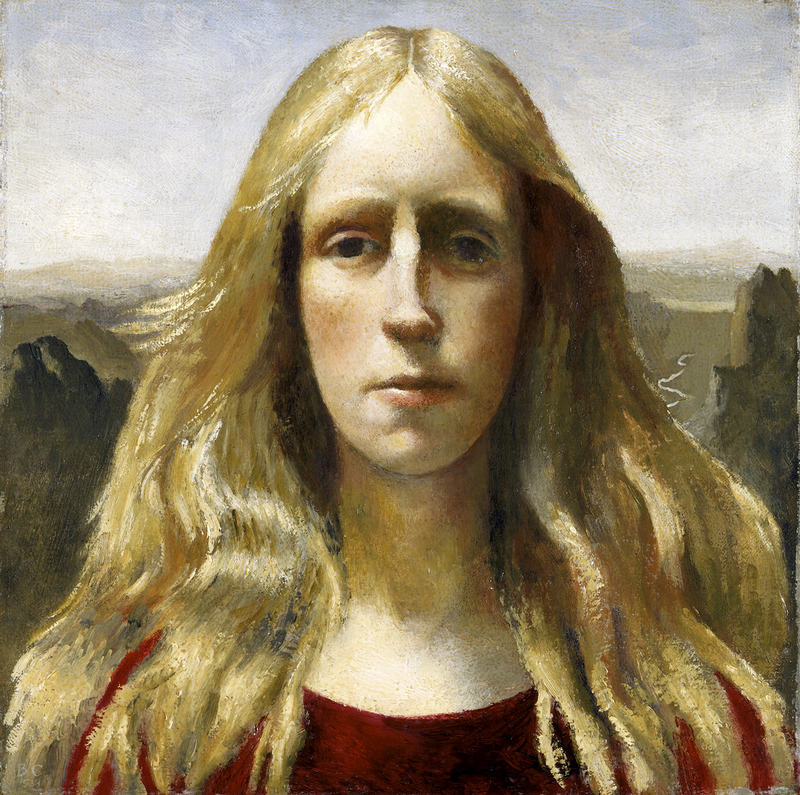

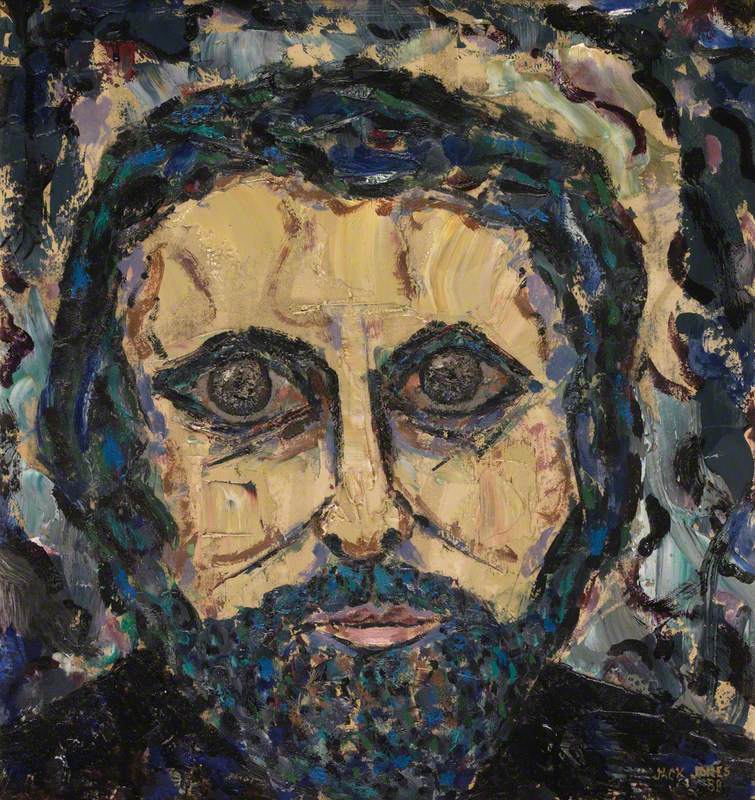

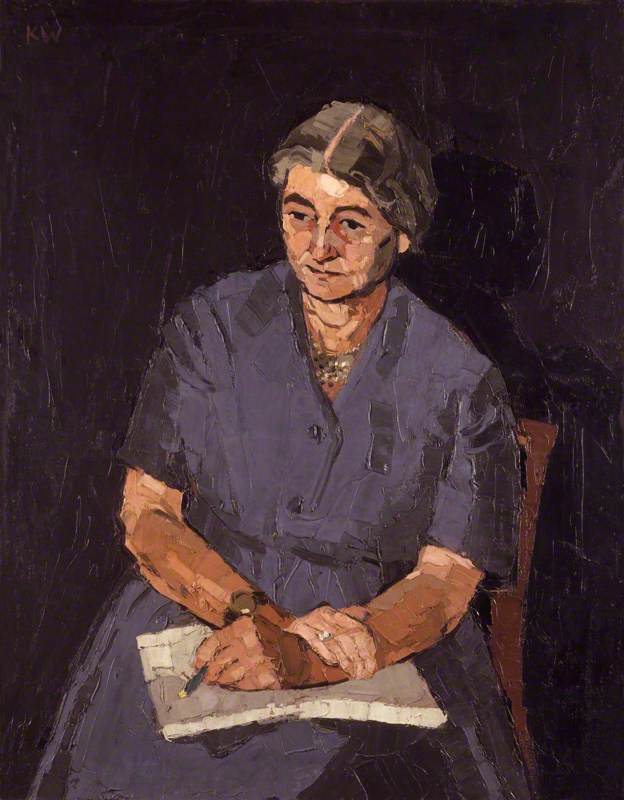

Kyffin's painting technique might appear unsuited to portrait-painting, yet in fact, he achieves brilliant likeness while conveying character too. The artist's own vulnerabilities attuned him to the sensibilities of others, and such trust and mutual sympathy can be felt in his portrayals of the artists Jack Jones and Eileen Younghusband.

Dame Eileen Louise Younghusband

c.1965

Kyffin Williams (1918–2006)

The act of painting was part instinct and part compulsion for Kyffin – a necessary means of seeking equilibrium. Inevitably, not everything an artist paints will be as good as their best work. Kyffin was a highly prolific artist but, to his detriment, not particularly focused on editing his work or getting rid of pictures that he didn't intend for the public to see. The fact that forgeries and fake Kyffins reach some lesser auction houses now also confuses the broader perception of his oeuvre.

Yet, in his finest pictures, a sense of immediacy is communicated powerfully to the viewer – a unique moment captured and rendered timeless. Here, we see the artist in his truest light.

Rian Evans, writer, critic and author of Kyffin Williams: The Light and The Dark

To view products relating to Kyffin Williams artworks visit the Art UK Shop.