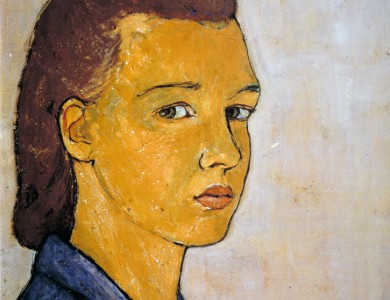

After fleeing Nazi-controlled Prague in 1939, Käthe Strenitz (1923–2017) eventually reached London's Liverpool Street Station.

She was 16 and one of the oldest of the 669 children whose escape from Czechoslovakia had been organised by the humanitarian Nicholas Winton.

'I saw this enormous black anti-diluvian station and felt what a horror and how interesting.' That first encounter with her adopted city informed her artistic vision which, in later years, concentrated on a small area around another London terminus – King's Cross.

Most of the 10,000 'Kindertransport' children who came to Britain were rescued from Germany, Austria and Poland. Many, including Käthe, never saw their parents again, only learning of their murder in Nazi death camps after the war. Käthe also lost her younger brother Michael who perished in 1944 at the age of 14.

'There was no-one of my lot who survived. No one,' she told the Imperial War Museum's oral history archive as she looked back on her life in 2000 when she was approaching 80.

Another child refugee orphaned by the Holocaust also became a painter. Rescued from Germany, Frank Auerbach (b.1931) was born eight years after Käthe. Curiously, their subject matter is strikingly similar.

The streets around Camden Town captivated both artists but while Auerbach is internationally acclaimed, Strenitz has received little attention.

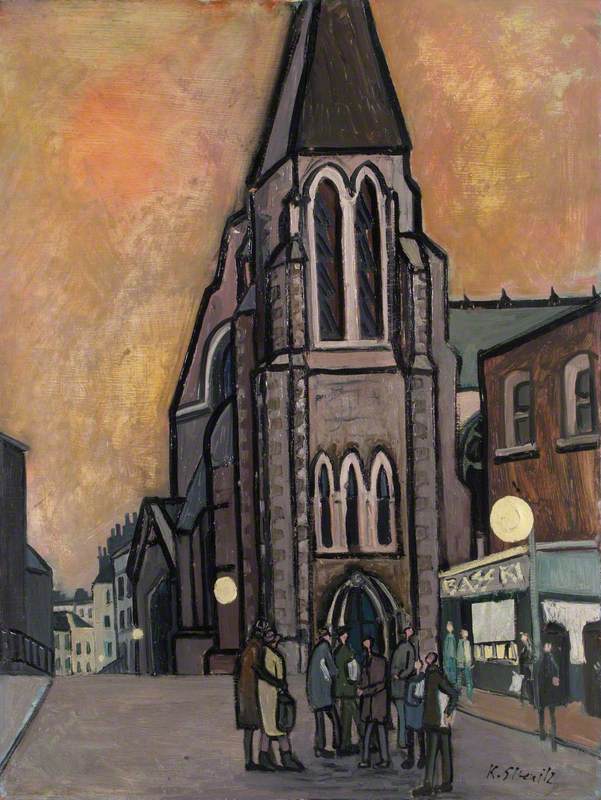

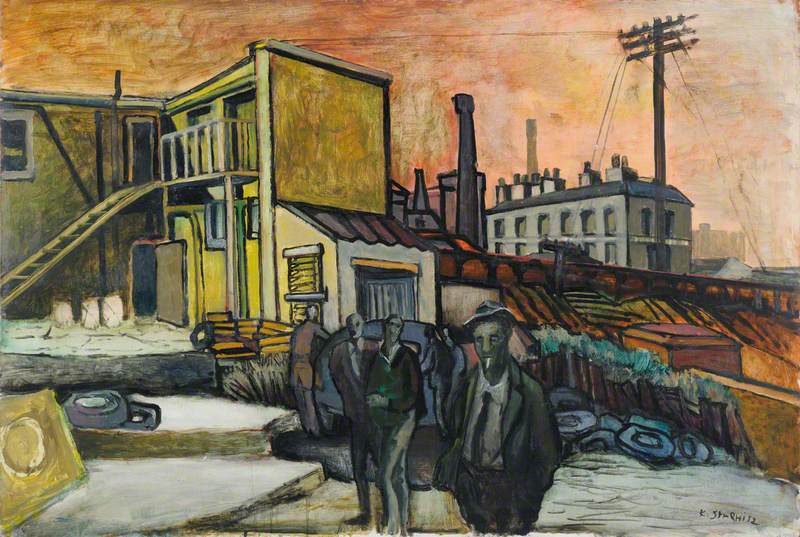

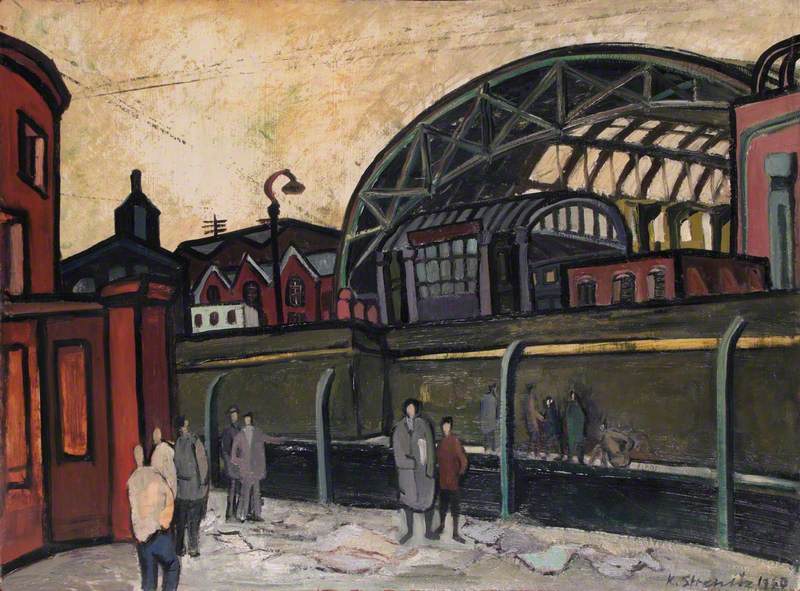

Far from 'green and pleasant', Kathe Strenitz's England is haunting, sombre and grimy. Her cityscapes, in paint and print, have considerable dramatic force. Occasionally, there is an air of menace as figures, often with featureless faces, gather in the gloom.

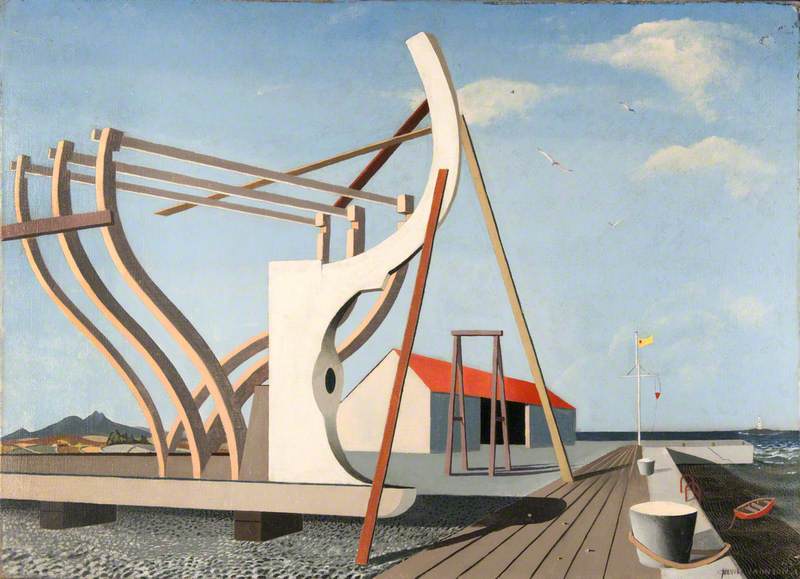

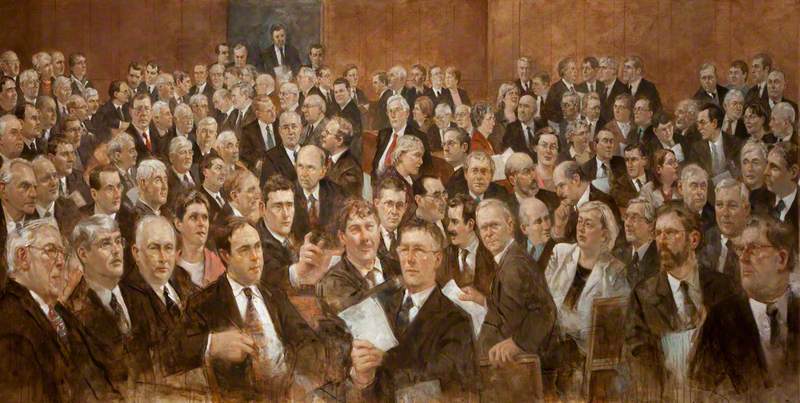

Entrance to a Factory near the Canal Entrance

(version A)

Käthe Strenitz (1923–2017)

Before her escape, Käthe had met the Austrian expressionist painter Oscar Kokoschka (1886–1980) in Prague. He later recommended her for a British Council Arts Scholarship at the Regent Street Polytechnic. This came after a miserable spell on a fruit farm in Hampshire where she was almost starved and had to sleep on the landing. After picking up a windfall apple, she was accused of stealing.

The Polytechnic was a disappointment. Ageing teachers with old fashioned ideas had come out of retirement to replace those needed for war. Nearly a decade later, after marriage and giving birth to a daughter, she returned and had a more positive experience with teachers including Norman Blamey (1914–2000) and David Thomas Smith (1920–1999).

By this time, her husband, Otto Fischel (1914–c.2010), had developed a plastic moulding business called Otaco Ltd in Camden Town. His factory, in Market Road, also became a base for her art and features in some of her paintings.

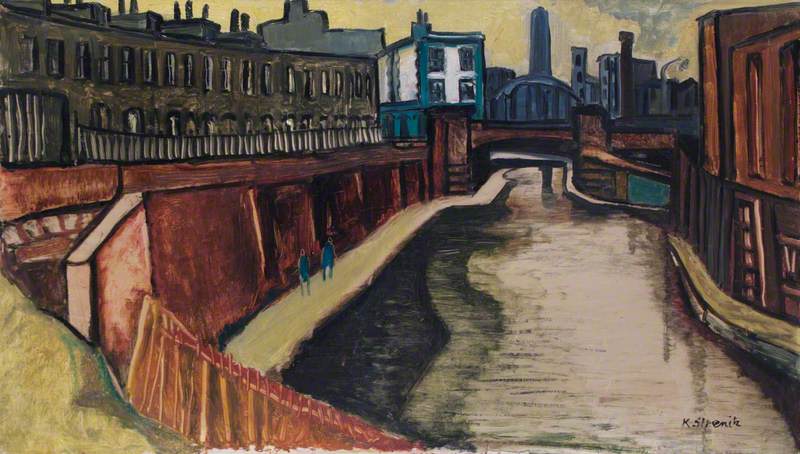

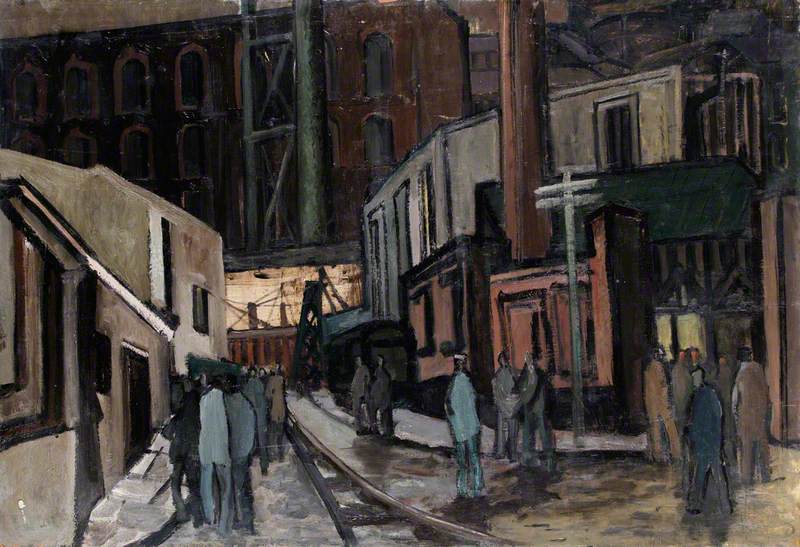

Backyard of Otaco Ltd Factory, 16 Market Road

Käthe Strenitz (1923–2017)

From then on, many of Käthe's subjects were within a five-mile radius of the factory. In another oral history project in 2005, 'King's Cross Voices', she said: 'I was always interested in the decline of the industrial scene and when my husband started a factory… I had an ideal place from where to work, so I tried to record as much of the neighbourhood as I could which included the canal, railway and the general landscape around King's Cross.' Industrial wastelands were her inspiration. Gasometers in Camley Street feature repeatedly in her work.

Far from the safest part of London, sometimes her husband's employees would accompany her on sketching trips. Otaco worker Alan Bratley, remembered her fondly: 'I drove Mrs F. (Fischel) to various locations and watched her draw… she was lovely.' During that period Käthe described how she felt particularly uncomfortable in the area around Regent's Canal. 'That was where you encountered groups of boys around 15 or 16 obviously not going to school.' She recalled one occasion when a gang of boys had killed some ducklings which a distraught canal worker had been trying to save.

Perhaps because of Kindertransport, both Auerbach and Strenitz made several images of railway stations.

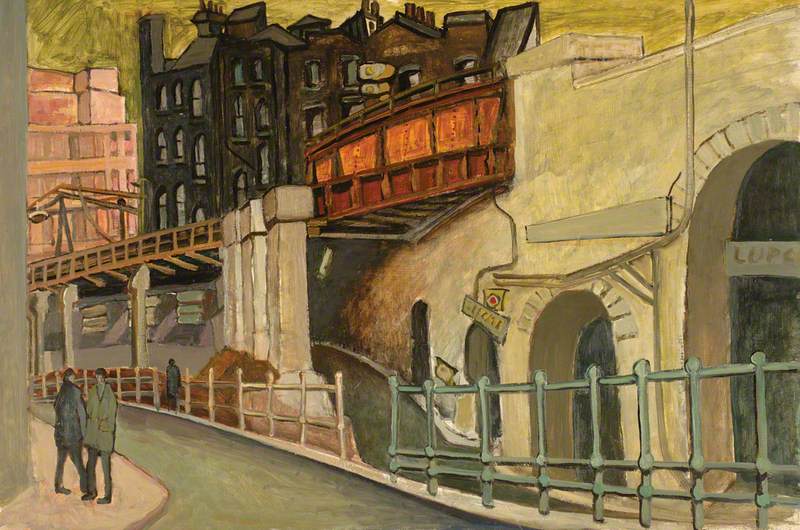

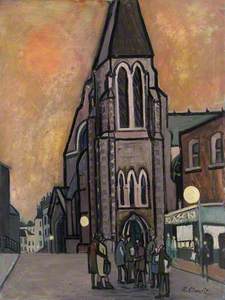

St Pancras Steps, Station

1978/1979

Frank Helmuth Auerbach (b.1931)

More than two hundred of Käthe's drawings of the streets and factories around King's Cross are held by the London Metropolitan Archive dating from the late 1950s to the 1980s. It is one of the most complete visual records of the area. Several are included in a recent book by Peter Darley called The King's Cross Story, which is dedicated to her.

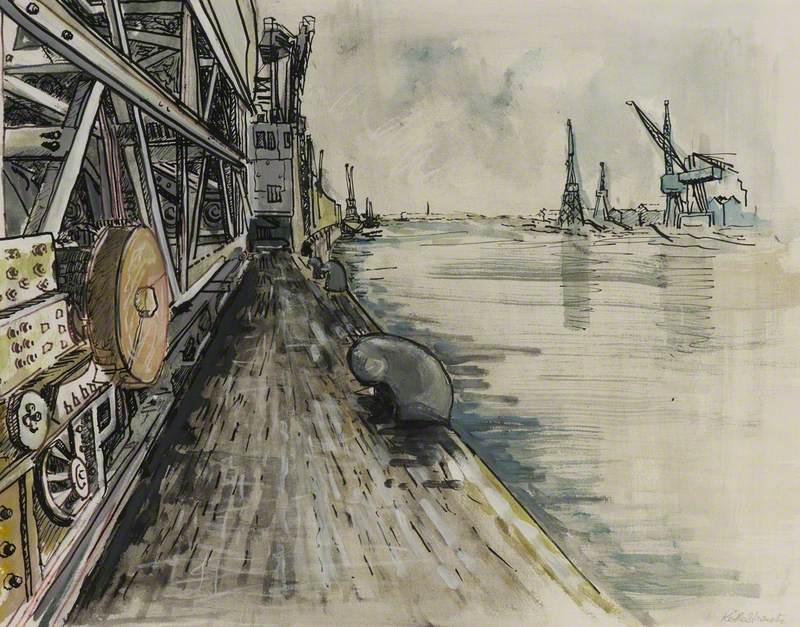

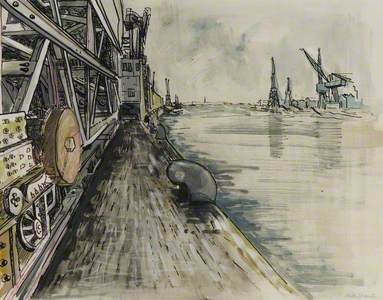

King's Cross Train Shed, Looking South across the Canal (?)

1960

Käthe Strenitz (1923–2017)

In later life, Kathe returned to her home town of Gablonz (now Jablonec nad Nisou) but found it didn't correspond with her childhood memories. 'I felt very little (emotion) when I went back,' she said, although she still thought Prague beautiful. Neither did she feel a strong attachment to her adopted country. 'I don't have any strong feelings at being at home here either… I don't have a desire to be part of something.' She avoided Kindertransport reunions and devoted herself to her family and her art.

As well as oil paintings, she did several pencil portraits and was particularly admired for her woodcuts, for which she received a Lord Mayor's award. In 1982 she became a fellow of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers and often said she considered her prints and drawings superior to her oil paintings.

Käthe Strenitz had some regret that she didn't confront her family's tragic history in her art, unlike those who made images of the Nazi death camps. 'I am not very heroic,' she said. But there is a dark thread in her fine body of work that can, perhaps, only be fully explained by her traumatic past.

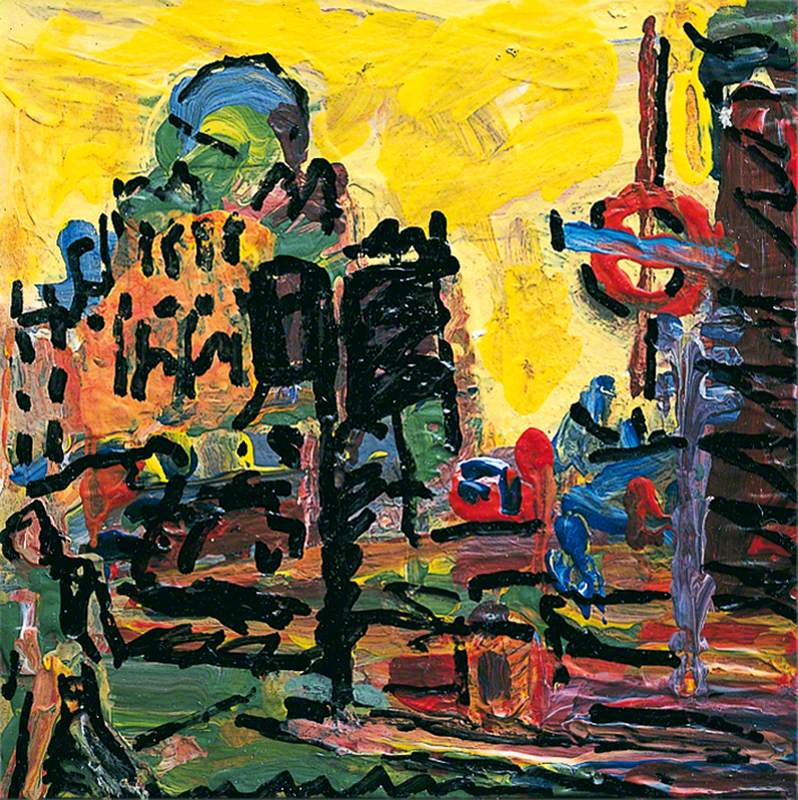

Entrance to a Factory near the Canal Entrance

(version B)

Käthe Strenitz (1923–2017)

James Trollope, author

James's latest book Rudolph Ihlee: The Road to Collioure will be published by Lund Humphries in May 2022