'Rule, Britannia! Rule the waves:

Britons never will be slaves.'

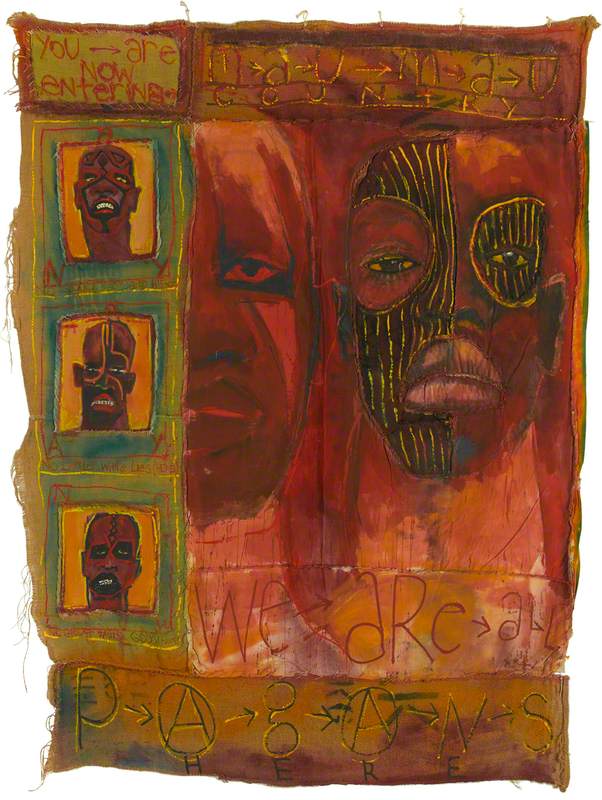

The lyrics from Rule, Britannia! written by James Thomson in 1740 encapsulate our country's not-so-distant colonial past, which Kara Walker confronts in her nautical-themed Fons Americanus, found in the cavernous space of Tate Modern's Turbine Hall.

Fons Americanus

2019, Hyundai Commission at Tate Modern by Kara Walker (b.1969)

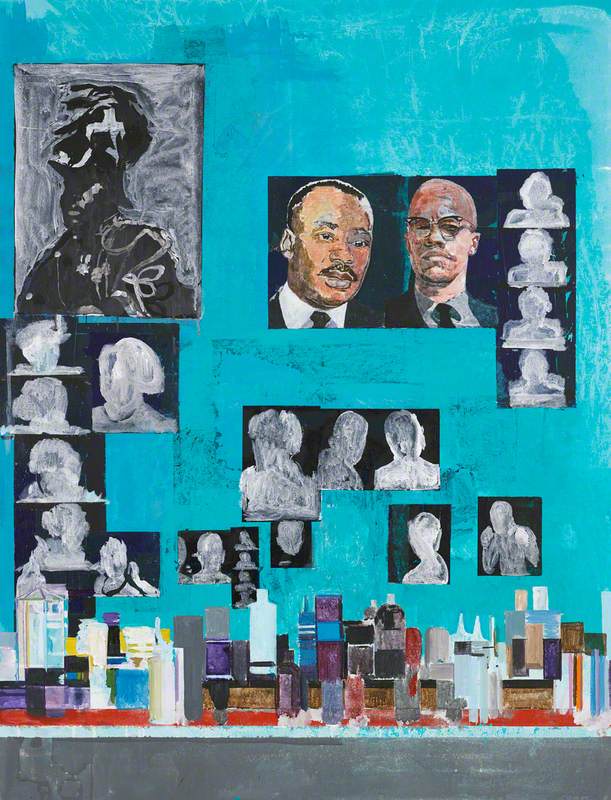

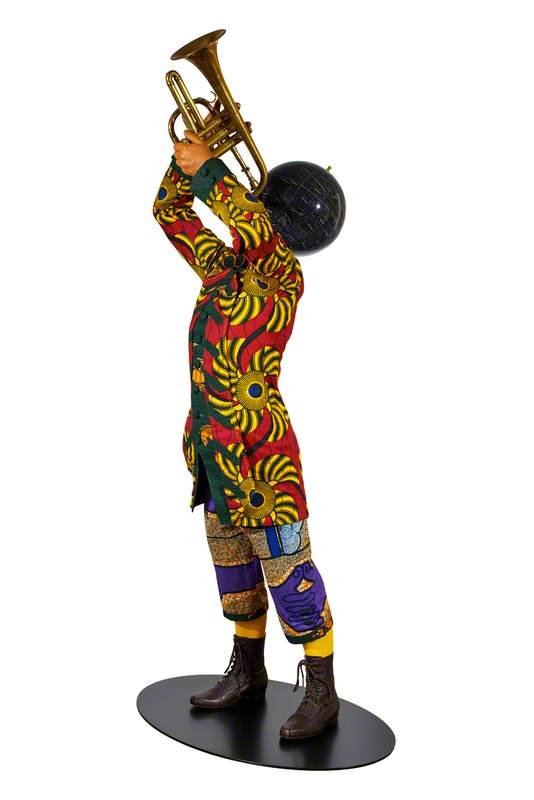

By investigating the traditions of European art history – underpinned by the narratives and wealth of slavery and empire – Walker's fountain reminds us of the imperial convention for ceremonious, patriotic art and public sculpture. Taking the Victoria Memorial as her starting place, Walker raises the following question: How should we treat public sculpture that continues to represent and glorify empire?

Embracing maritime themes, Walker's fountain satirises Britain's evocation of 'Britannia' and other mythical, sea-based allegories, which underpin our historic self-fashioned image as a small island nation who was once the 'ruler of the seas'. This myth was once instrumental in shaping the transatlantic slave trade: an economic slave system that once interconnected Africa, Europe and America.

However, Walker moves beyond British national borders to encompass themes pertaining to the wider 'African diaspora' – the global community of historically displaced individuals still subject to the macro and micro repercussions of racism and imperialist power dynamics.

Her work is a necessary confrontation and an 'anti-monument' to colonialism, which nevertheless gives representation to those who were previously submerged under the weight and shame of colonial history. But to decode the many layers of Walker's Fons Americanus, we must start with the 'fons et origo' of European art history and its problematic misrepresentations of slavery and colonial society.

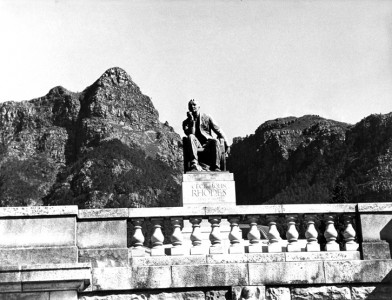

The Victoria Memorial

Completed in 1911, the Grade I listed sculpture is situated directly outside of the royal residence of Buckingham Palace and was funded by the British Empire: Canada, Australia, New Zealand and from goods transported from West Africa. Adopting a nautical theme, the monument depicts Queen Victoria amongst mythical creatures of the sea: mermaids and mermen.

Victoria Memorial (Buckingham Palace, London)

1901–1924, bronze & white marble by Thomas Brock (1847–1922)

Fact and fiction intertwine in this grand allegorical monument created to celebrate the legacies of empire under Queen Victoria's reign. At the apex of the sculpture stands the golden-winged Victory, a symbol of Queen Victoria, or the goddess 'Victoria', who stands on a globe with a victor's palm in her right hand.

In direct response, Walker's humorous fountain contains 'Queen Vicky' – a lively, almost caricatural African woman, who holds a coconut rather than a globe. Her voluminous skirts shelter a crouching figure who is the personification of melancholy. Nearby, a noose hangs from a sculpted tree trunk, a sinister reminder of another recent history from across the Atlantic, albeit equally connected to imperialist, racist attitudes.

Queen Vicky, Fons Americanus

(detail), 2019, Hyundai Commission at Tate Modern by Kara Walker (b.1969)

At its inauguration in 1911, George V unveiled the memorial personally, while the then-Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, delivered speeches to a large public gathering. Sir Thomas Brock, the designer of the monument, was famously knighted on the spot, while Sir Aston Webb was celebrated for designing the wider architectural setting and memorial gardens.

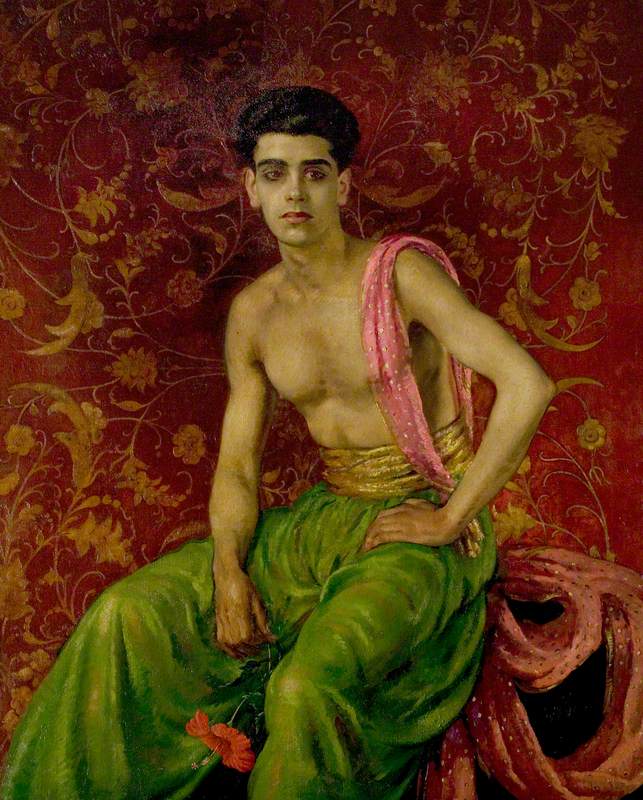

Venus and the 'Sable Venus'

In contrast to the winged Victory at the summit of the Victoria Memorial, Walker places a variant of the goddess Venus at the apex of Fons Americanus. A sculptural element that is also part of the fountain, this Caribbean or African Venus spurts jets of water out of her breasts in a comical fashion.

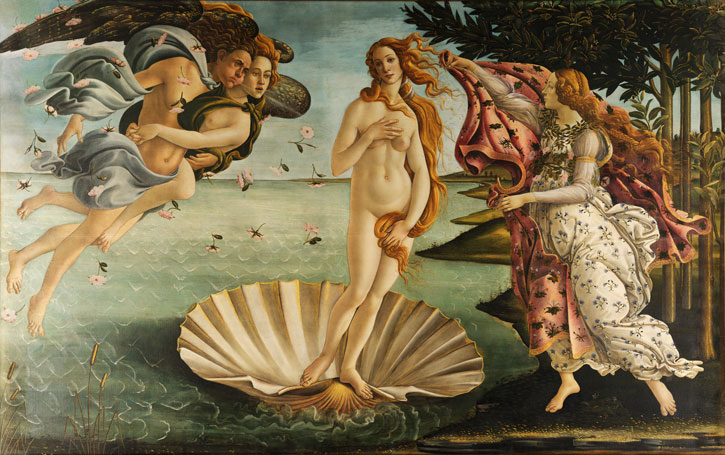

A play on the traditional archetype of 'Britannia' as a robed, athletic white woman holding the trident of Poseidon and wearing a Corinthian helmet, Walker's bountiful Venus harks back to racialised tropes of 'Mother Africa' found in European art history, as well as Renaissance representations of Venus emerging from a seashell, as seen in Botticelli's masterpiece, The Birth of Venus.

The Birth of Venus

c.1485, tempera on canvas by Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

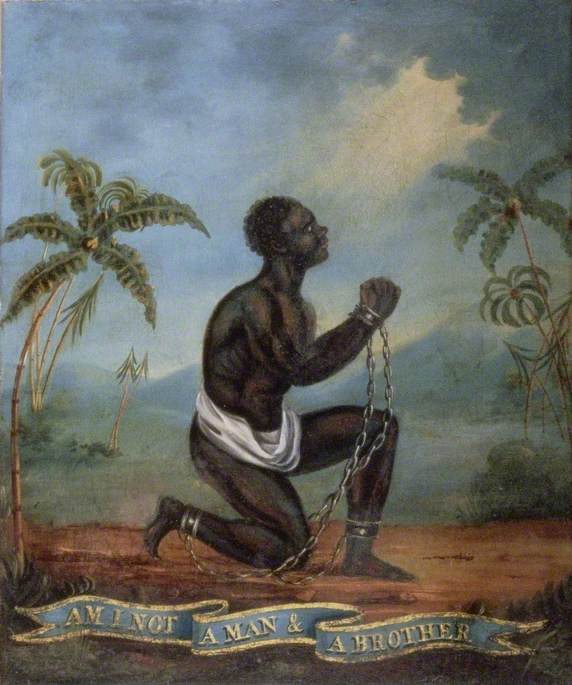

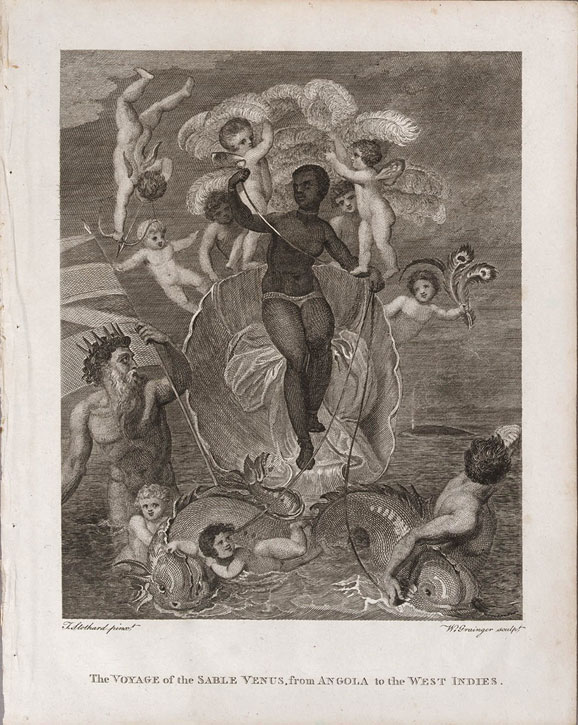

Walker refers to Thomas Stothard's slave propaganda image The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies – an image directly inspired by Botticelli's Venus.

The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies

c.1800, etching with engraving by Thomas Stothard (1755–1834). Michael Graham-Stewart Slavery Collection. Acquired with the assistance of the Heritage Lottery Fund

The etching originally appeared alongside Isaac Teale's The Sable Venus. An Ode (1793) in the third edition of Bryan Edwards' The history, civil and commercial, of the British colonies in the West Indies (1801). Edwards was a politician who inherited many Jamaican plantations and was vehemently opposed to abolitionism.

To the left side of Strothard's Venus stands Triton holding the British flag as he guides the seafarers across the ocean. This alludes to the 'Middle Passage', the name given to the Atlantic trade route by which captured African people were shipped to the West Indies bound in chains. The etching is pure propaganda, as it sanitises the monstrosities of slavery through allegory.

On top of this, the image of the African 'Sable' (black) Venus suggests the fetishisation and sexual exploitation of enslaved females, a principal theme in Teale's eighteenth-century poem. Walker deliberately adopts this theme in her Venus, who, upon looking a little closer, is physically violated – her throat is slit and water spurts out of her wound.

Fons Americanus

(detail), 2019, Hyundai Commission at Tate Modern by Kara Walker (b.1969)

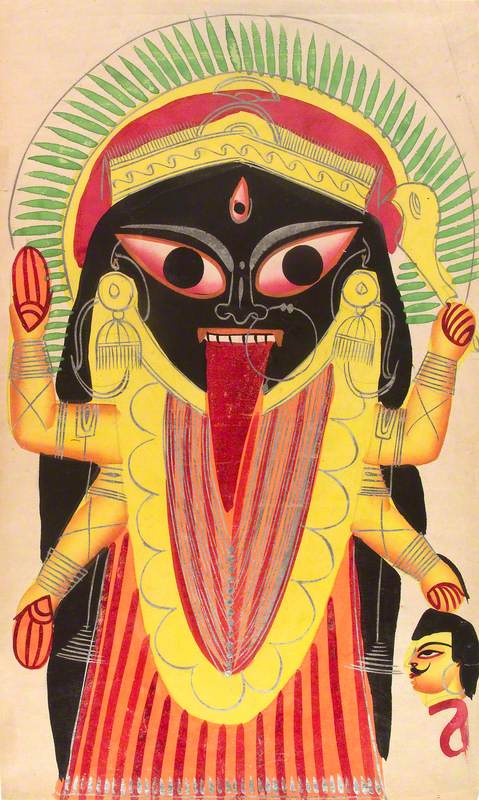

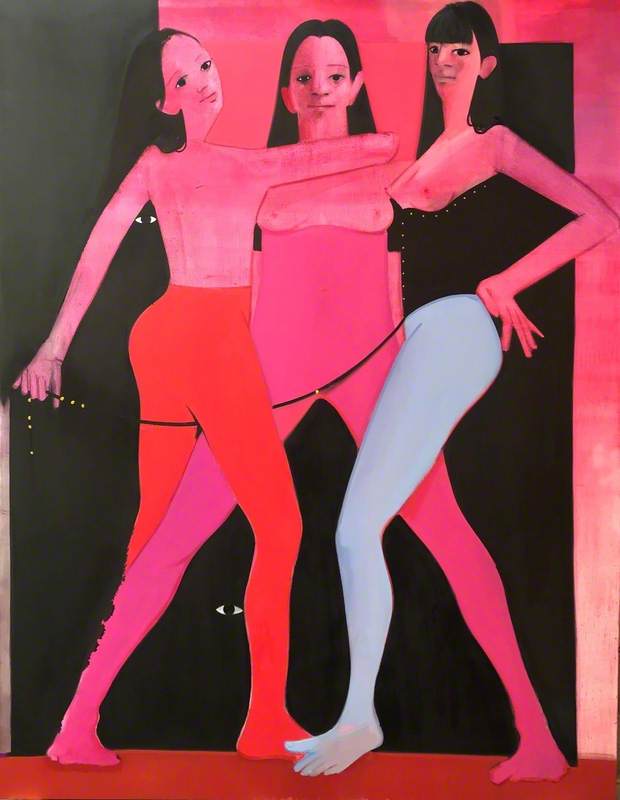

The Four Continents and feminisation of 'Africa'

In the period after Europeans first sailed to the Americas, and before European voyagers discovered the entirety of the earth, they divided the world into four continents, often called the 'Four corners of the world' – Asia, Africa, Europe and America.

Africa, Personified by a Simulated Bust in an Ornamental Niche

mid-17th C

British (English) School

In European art, these continents were personified by different allegorical figures and forms of iconography, as seen in works by Rubens, Zucchio or the sculptor Bernini, who used this subject for his Fountain of the Four Rivers in Rome's Piazza Navona.

La femme Africaine (An African Venus)

1867

Charles Henri Cordier (1827–1905)

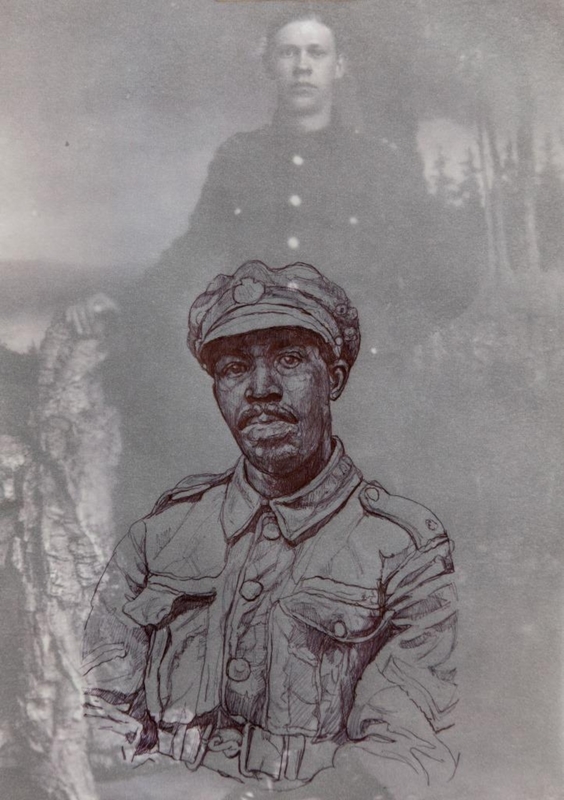

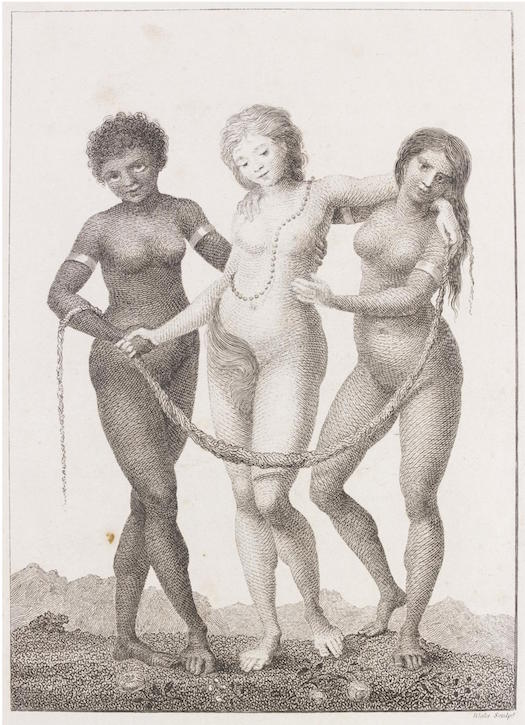

In 1796, William Blake created the allegorical engraving Europe Supported by Africa and America, following the artistic tradition of the 'Four Continents'. Gold bands – to represent enslavement – appear on the upper arms of the darker-skinned females who flank the white woman, the embodiment of 'Europe'.

Europe Supported by Africa and America

1796, engraving by William Blake (1757–1827)

The Scottish-Dutch soldier John Gabriel Stedman had witnessed the atrocities committed against enslaved peoples under the Dutch West Indian company in the 1770s, leading him to write Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, a book which called for reform. Blake's illustrations appeared in this bestselling and controversial publication, reflecting his abolitionist sympathies.

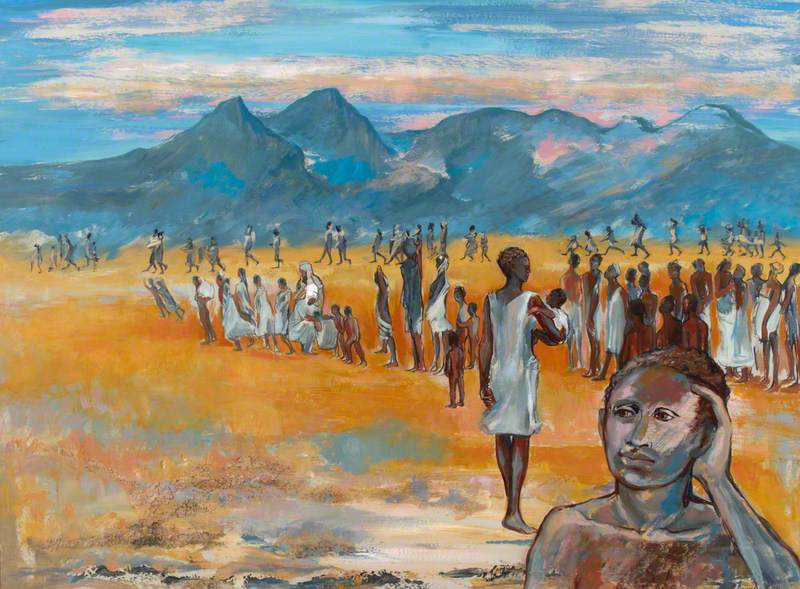

Slave ships and shipwrecks

'We cross the Atlantic in many ways. We Swim or we Sink. The Voyage of the Sable Venus, submerged within her misshapen shell.' – Kara Walker

Walker's monument refers to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century paintings that often distorted the realities of crossing the Atlantic by ship or boat.

One painting that didn't sanitise the horrors of the Middle Passage was J. M. W. Turner's The Slave Ship, originally titled Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming On.

The Slave Ship

1840, oil on canvas, by James Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

The work was exhibited in 1840 and illustrated a true, notorious incident – the Zong massacre. In 1781, the captain of the Zong slave ship, Luke Collingwood, threw overboard 133 enslaved individuals during a storm, so that he could protect his cargo and collect insurance money. Ultimately nobody was ever prosecuted and those murdered were categorised as 'cargo' rather than as 'humans'.

The subject sparked Turner's interest after reading Thomas Clarkson's The History and Abolition of the Slave Trade. The image of the Zong in a nightmarish whirlpool has served as a powerful emblem for the inhumanity of the transatlantic slave trade.

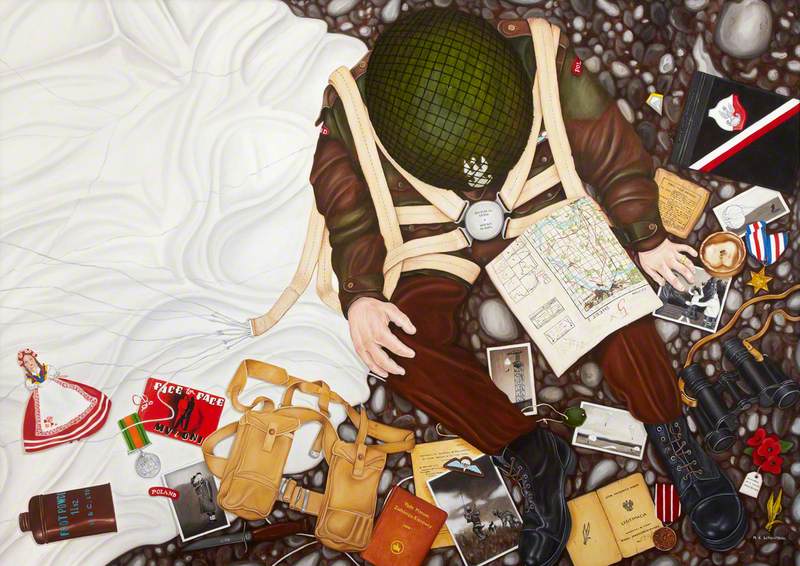

A Remarkable Occurrence in the Life of Brook Watson

1778

John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) (copy of)

John Singleton Copley's Watson and the Shark (1778) is another nautical-themed painting referenced by Walker, alongside Winslow Homer's The Gulf Stream (1899). Walker inscribed the words 'K. West' on the side of her sculptural boat – a gesture in homage to Homer's boat signed 'Key West'. While Walker refers to a historical painting, she brings her version up to date by referencing the rapper Kanye West, an outspoken cultural figure who has often brought to the fore discussions about racism and slavery.

The Gulf Stream

1899, oil on canvas by Winslow Homer (1836–1910)

More widely, Walker's practice attempts to display the barbarity of seafaring across the Middle Passage, and the misrepresentation of such voyages in art history. Inspired by Turner's The Slave Ship, she created Grub for Sharks: A Concession to the Negro Populace in 2004, using her trademark black silhouettes to address historic black caricatures and stereotypes.

Fons Americanus

(detail), 2019, Hyundai Commission at Tate Modern by Kara Walker (b.1969)

In the context of Fons Americanus, Walker wrote: 'I looked at the grand panorama of a whaling voyage and considered the Black Atlantic as its been represented by Turner, Homer and Copley and sailors themselves...'

Responding to historic paintings of the Middle Passage, Walker plays with motifs of refuge and shipwreck. Inside sculptural reliefs of the fountain, African figures weep tears, while in the watery basin, figures perish among sharks.

In this sense, Walker's fountain alludes to the themes of the colonial past. But by evoking sea voyage and hopes for refuge, her work also resonates with the migrant crisis of today.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK