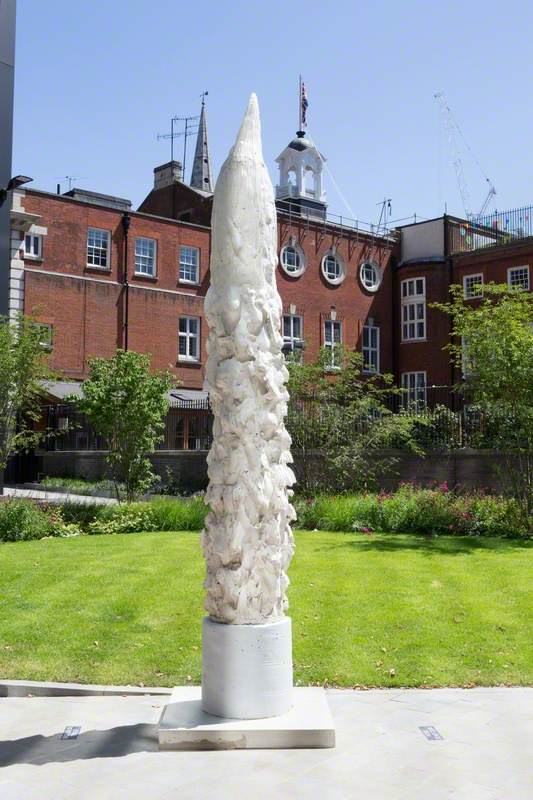

Climb, the sculpture in London's Mitre Square, looks like the traces of someone fighting for dear life. Hands clawing through clay, desperate to find something solid to hold on to. There is no body to speak of, only the leftover marks.

If classical figurative sculpture strives to be a moment caught in time, Climb is the capture of movement in the absence of the figure. Its architect and author, Juliana Cerqueira Leite (b.1981), originally from Brazil, has taken the development of sculpture, in its classical sense, to a new level by creating a work where the twisting and writhing of the body is more profound through its absence.

Climb (detail)

2012, Forton MG, steel & urethane foam by Juliana Cerqueira Leite (b.1981)

The sculpture is a white obelisk form with, what on first encounter looks like the base of a palm tree, turns out to be imprints of the sculptor's body pushing out of, and not into, the trunk-like form. It is easy to get hung up on how it was made. There are elbows, toes and pulling finger marks all up the sculpture which tapers off to a pyramid of streaks that look like someone was desperately trying to dig themselves out in reverse. There is a foreboding sense of violence, like something bad happened here.

Climb (detail)

2012, Forton MG, steel & urethane foam by Juliana Cerqueira Leite (b.1981)

And how is it done? What Leite did was a cast relief of herself digging her way through the sculpture. Let me explain in a bit more detail.

Making of 'Climb': mould sections being assembled

Sculpture Space Residency, Utica, NY, 2011

Leite built a large and tall tube out of wood and lined it with 3 tonnes of clay, her favourite material (along with plaster). She then stood it up on its end and lifted it much in the way a car mechanic lifts a car to look at its underbelly so that she could crawl in and proceeded to climb up, gripping the soft wet clay with her hands and feet as she made her way up the 3.5 metres.

Making of 'Climb': filling the mould with clay

Sculpture Space Residency, Utica, NY, 2011

She then made her way back down the sculpture and filled it with Forton MG, a material often used on exterior mouldings for its malleability and hardening qualities, before peeling away the wood exterior and clay, to reveal a relief of the removed shell.

Making of 'Climb': opening the mould

Sculpture Space Residency, Utica, NY, 2011

I am reminded of the works of Rachel Whiteread who, like Leite, casts the inverted empty space to reveal the trace left behind by an object. When Whiteread's casts, like with her Trafalgar Square Plinth project, the results are crisp and smooth with perfectly straight lines afforded by using plastics or polished concrete, Leite's sculptures are anything but. They use a similar technique but with widely differing results.

Climb (detail)

2012, Forton MG, steel & urethane foam by Juliana Cerqueira Leite (b.1981)

What Leite accomplishes with her sculptures is to permanently cast an impression of a movement. The shapes and forms that her body created in movement, something which is fleeting by nature, like a dance, is made permanent by her artistic efforts.

Climb (detail)

2012, Forton MG, steel & urethane foam by Juliana Cerqueira Leite (b.1981)

Looking up at the large white (rather phallic) form, the eye darts from one detail to the next. Finger marks digging and groping, feet pushing into the air, determined elbow imprints, all clawing upwards in an invisible struggle.

The Rape of Proserpina

1621–1622, Carrara marble sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), Galleria Borghese, Rome

Analysing her toes, I am reminded of Proserpina's toes in Bernin's sculpture of her rape. Her limbs are tense with anguish and struggle as Pluto violently abducts her to the underworld. His fingers are pressing into her thigh animating the sculpture to look like real flesh. It is as though with Climb, Leite has captured Proserpina's movements, her upwards struggle to get out of Pluto's grip and the speed of the action.

The Rape of Proserpina (detail)

1621–1622, Carrara marble sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), Galleria Borghese, Rome

Leite is not being as literal as to tell a specific tale but seems to be hinting at something more universal. She is expressing the emotions surrounding the story, feelings of terror, flight, jerky spasms of movement. To the point that the artist is content for it to be seen as a performance piece. Leite likens her sculptures to a sediment of memory, where the sculpture is a witness to her actions, forever present.

Unlike so many of her contemporaries, Leite still makes sculpture. She doesn't assemble them or get technicians to build it for her; one can really see how she has physically carved and moulded the work. Her body sets the size and limitations of the piece which is more abstract than figurative.

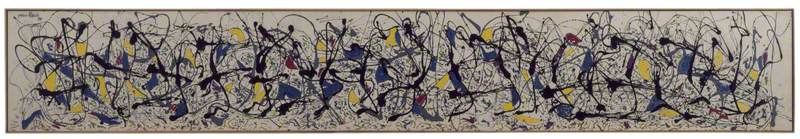

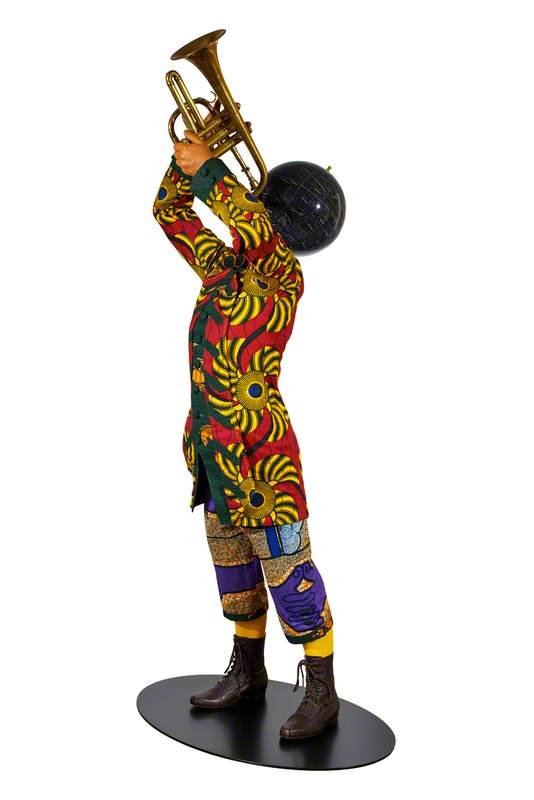

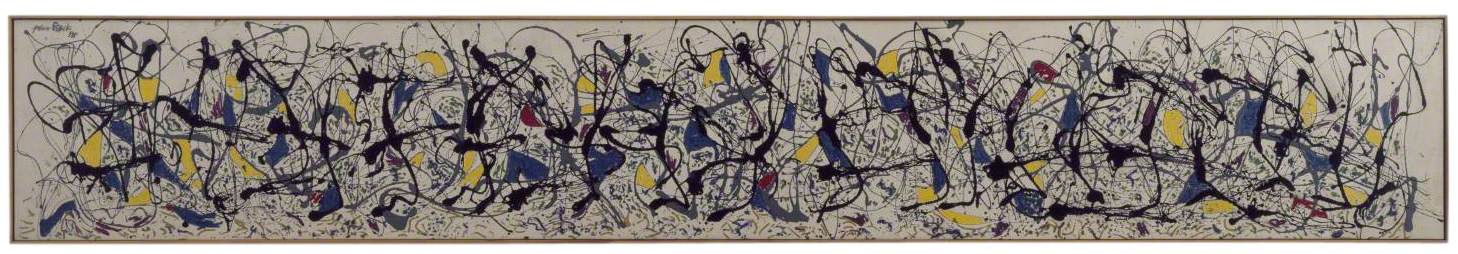

She has been compared to Eva Hesse or Lynda Benglis for her use of industrial materials, but, to my mind, her work puts into three dimensions that physical movement which Jackson Pollock achieved in his drip paintings.

You can see the work for yourself in Mitre Square as part of the Sculpture in the City initiative. The pallid white form is quite striking in this domestic, quaint patch surrounded by the mighty jungle of the City.

I have shied away from writing that this is a symbol of female struggle in very male surroundings, but it is hard to avoid, especially when reading up on the history of the square. The square became infamous as the site of the murder of Catherine Eddowes by Jack the Ripper in September 1888. This, of course, has nothing to do with the sculpture, but it does colour the way it is seen.

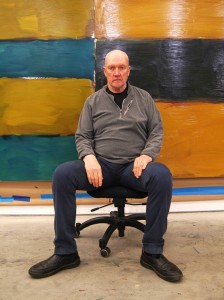

Maya Binkin, founder of The Art Pilgrim