One of my hobbies as a teenager was visiting the medieval churches of my native Derbyshire. This interest was caused by my father’s limitation of our excursions to within the county boundaries. We were from the small village of Temple Normanton in the north-east of the county, hence trips further south in the direction of Derby were much rarer, my father preferring to inspect such neighbouring sites as the church at Ault Hucknall, a partly Saxon building where the seventeenth-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes is buried.

However, one day we were intrepid and went 20 miles south to look at the melancholy ruin of Dale Abbey. It consists of a single vast window arch of c.1300 on the edge of a field. There were also visible foundations of the crossing tower of the Abbey church and bits of the chapter house. Close by is the little medieval church of the village of Dale, set near a low cliff.

When I came across the exquisite landscape by Joseph Wright of Derby in the Graves Gallery at Sheffield I realised immediately that it was Dale. I wrote an undergraduate letter to the then director Frank Constantine about it. The picture was of course published in Benedict Nicolson’s magisterial monograph on Wright in 1968. The artist exaggerated a little the height of the cliffs behind the site and introduced more water – today there is only a stream.

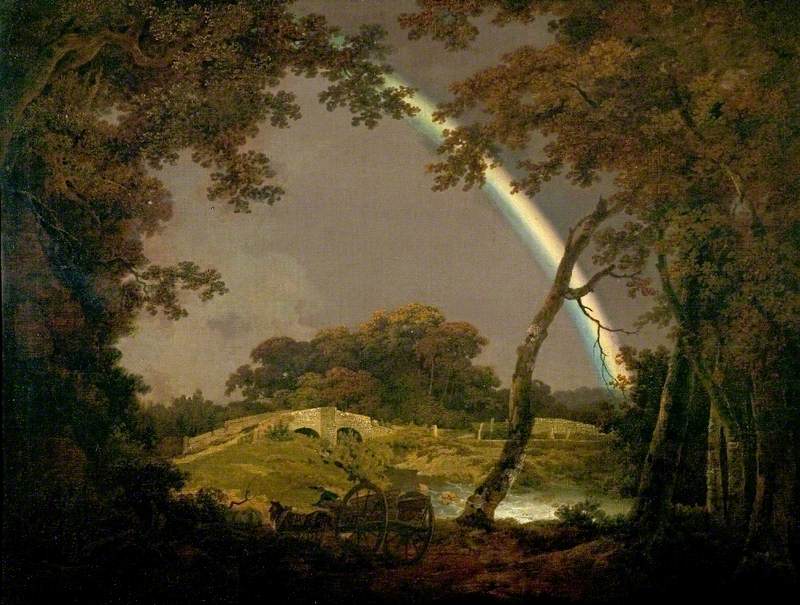

In fact Wright painted very few Derbyshire landscapes other than those of Matlock and the nearby Arkwright Mills at Cromford. But one of Wright’s best landscapes, entitled Landscape with a Rainbow, at Derby Museum and Art Gallery, was recognised as a specific site, and studied by Dr David Wakefield, a former colleague of mine from the Courtauld Institute, resident at Ogston Hall.

He realised it was a view of a little bridge destroyed by the coming of the main railway line from Derby to Chesterfield. This railway line was built under the aegis of George Stephenson who died in Chesterfield in 1848. David published his findings in the journal, Derbyshire Life and Countryside, but I don't think the information made the caption in the Public Catalogue Foundation’s Derbyshire printed volume.

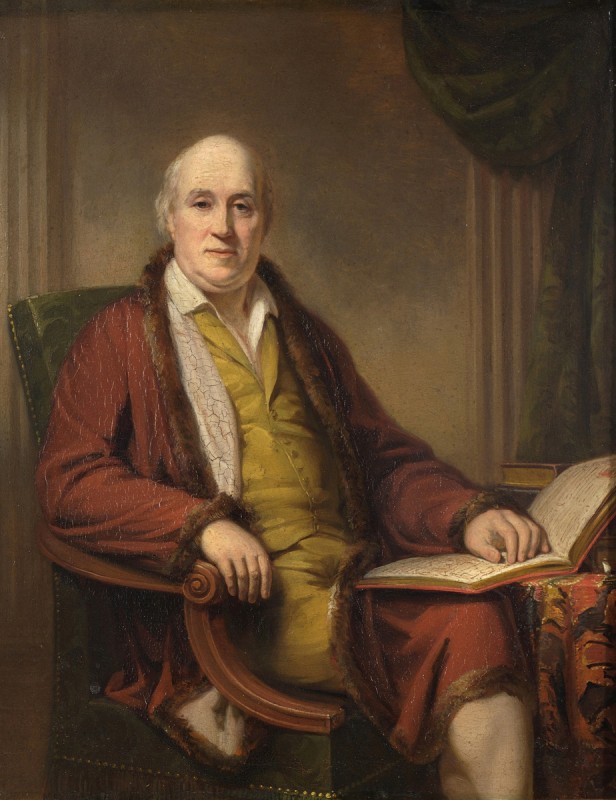

When I began to collaborate with Benedict Nicolson on Georges de La Tour, myself as compiler of the catalogue raisonné and Nicolson as the author of the text, he remarked one day (this was in 1969): ‘Oh, Christopher, if I had known you just a little earlier, you could have helped me so much with Derbyshire.’ Ben had also remarked that a stay at Hardwick Hall as the guest of Evelyn, Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, had not been a success. Perhaps he had asked her rather too many questions about local topography.

Christopher Wright, Art UK advisor, art historian, artist and author of numerous catalogues of Old Master paintings in Britain