In 1925 The Sunday Times art critic and campaigner for women's suffrage Frank Rutter proclaimed that Jessica Dismorr's (1885–1939) solo exhibition 'should be seen by all interested in the modern movement.'

Forty years later, art historian William Lipke observed that Dismorr's work 'illustrates in capsule form the stylistic development of twentieth-century British art.'

That Dismorr was so admired yet has largely disappeared from art history can be ascribed, partly, to the fact that she was a woman, and also to her suicide just before the outbreak of the Second World War. There was no opportunity or energy in September 1939 to mount a retrospective.

Apart from glimpses of Dismorr's art in Vorticist exhibitions, she has not been a presence in museum shows, and the range and radicalism of her work has been largely overlooked.

In fact, from the beginning of her career, Dismorr chose to put herself in a progressive environment. She was one of five daughters (a son died in childhood) of an Australian couple who made a fortune in business and settled in England. The Dismorr girls were allowed to study and had the money to pay for it.

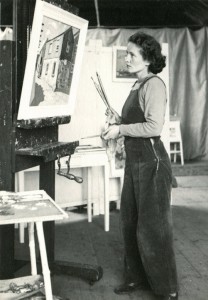

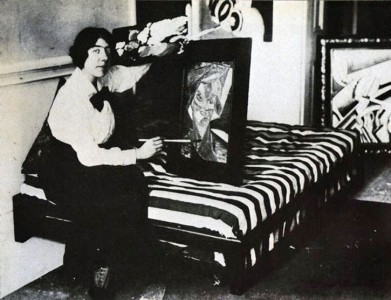

The Slade School of Fine Art, where Jessica enrolled in 1903, was at the time renowned for its teaching of drawing – and for allowing women to work from the life model like men. The sureness of construction and economy of line learnt there was to characterise Dismorr's work throughout her life.

From the Slade, Dismorr travelled to Max Bohm's art school in Étaples then to the Académie de la Palette, Paris.

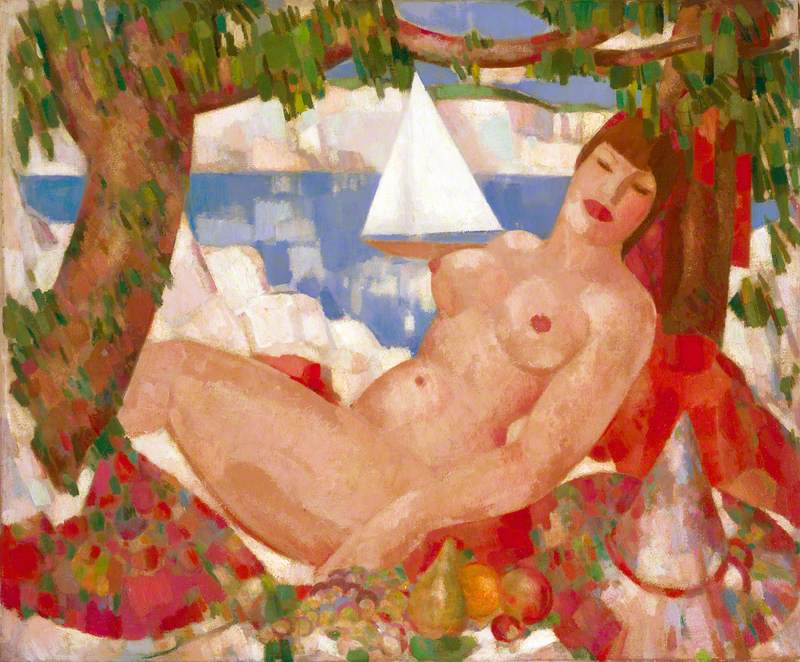

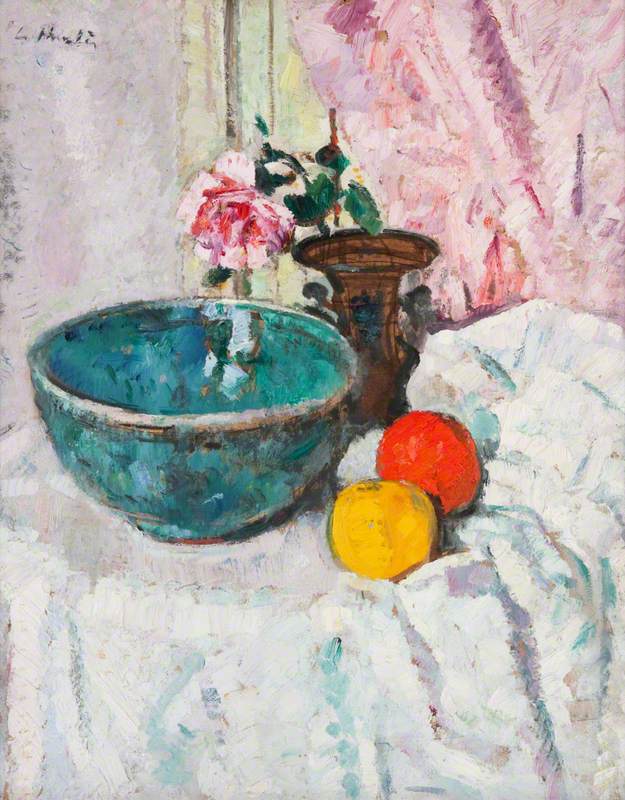

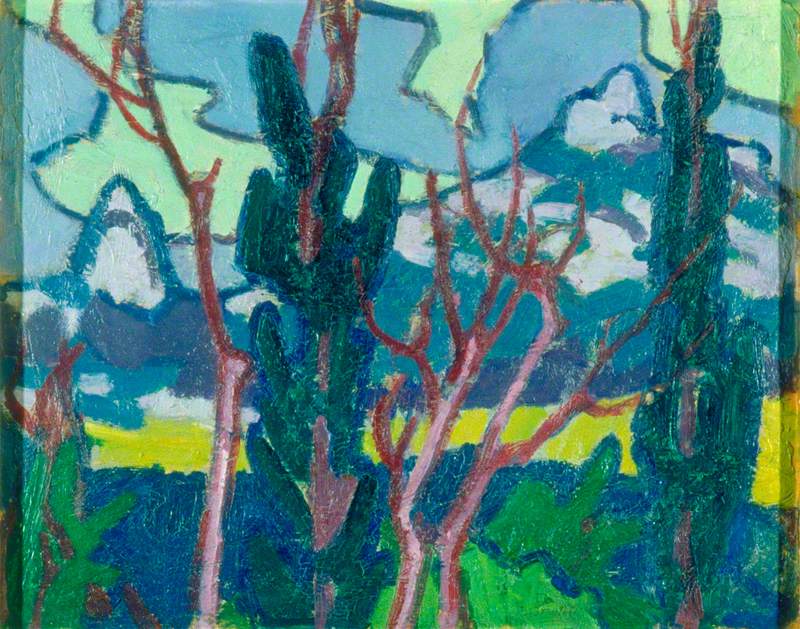

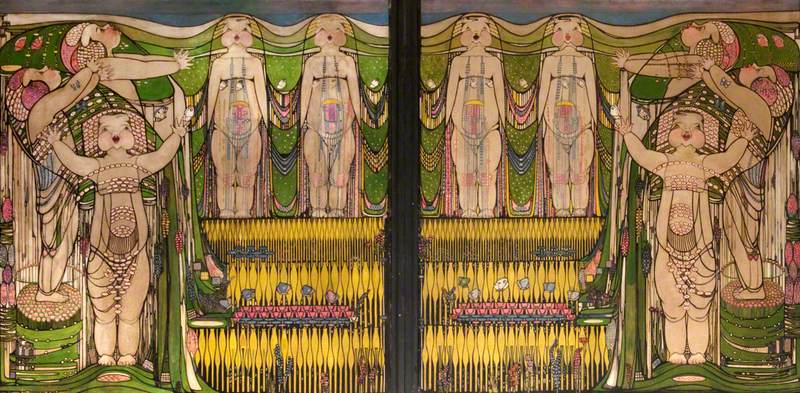

It was in Paris that the first of the movements Dismorr joined – Rhythm – was formed. Centring on the Scottish painter John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961) and his partner the American artist Anne Estelle Rice (1877–1959), the group sought to unite all the arts in a Bergsonian expression of the fundamental rhythm of existence. The critic John Middleton Murry and his lover, later wife, the writer Katherine Mansfield, edited an influential journal under the group's name.

Leafing through the pages – and the catalogue of Rhythm's only exhibition, held at the Stafford Galleries in the winter of 1912 – the presence of women members is striking. Along with Dismorr, the artists included Anne Estelle Rice, Marguerite Thomson (1887–1968) (later Zorach), Dorothy 'Georges' Banks and Ethel Wright.

What is little known is that at the Rhythm exhibition the radicalism of the Fauve experimentation in the art on the walls was allied with political radicalism, in the form of Wright's imposing portrait of Una Dugdale Duval.

Dugdale Duval, an activist for women's suffrage, caused a national scandal in 1912 when she refused to include the word 'obey' in her marriage vows to Victor Diederichs Duval, a close friend of Frank Rutter and member, with him, of the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement.

Modern art and radical politics also came together in the movement that became Dismorr's next home as an artist: Vorticism.

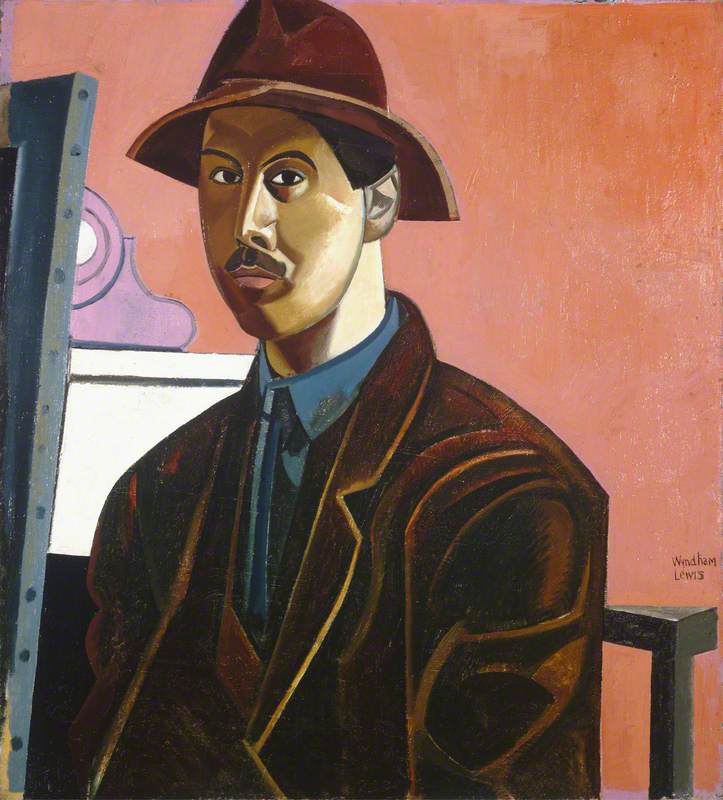

With her fellow painter and friend Helen Saunders, she signed the movement's manifesto in 1914, the only two women out of eleven members who included Wyndham Lewis, Henri Gaudier Brzeska and Ezra Pound. Dismorr's art and her writing featured in the Vorticist periodical, Blast, in whose pages the group supported the campaign for women's suffrage. Writing 'To Suffragettes' in Blast, Lewis proclaimed 'We admire your energy. You and artists are the only things... left in England with a little life in them.'

Blast notoriously published lists of those whom the Vorticists 'blasted' or 'blessed' – among the blessed was 'Mrs Duval'.

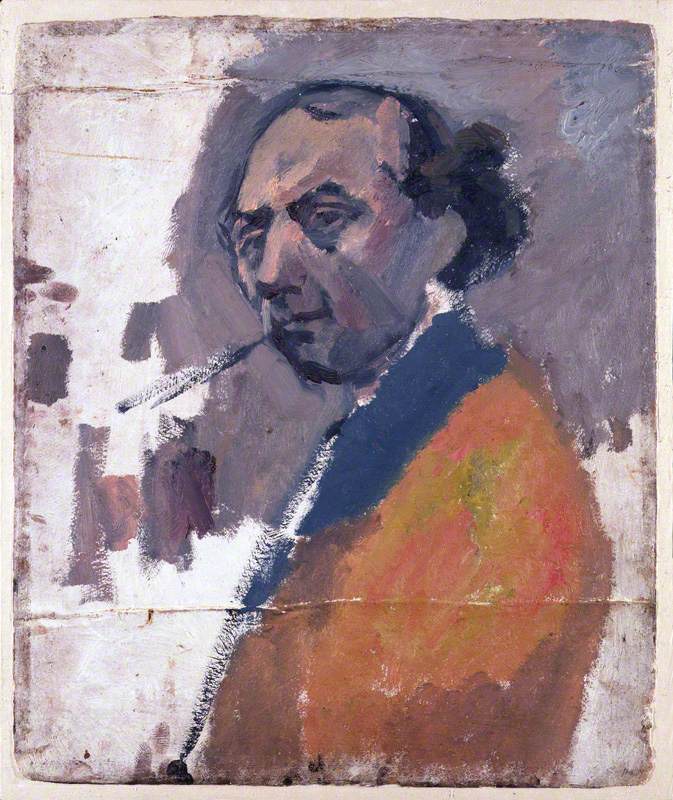

The war put an end to Vorticism, and it also stopped Dismorr from painting for a time. She worked as a nurse in France, and suffered a nervous breakdown. Recovery signalled a change in her practice.

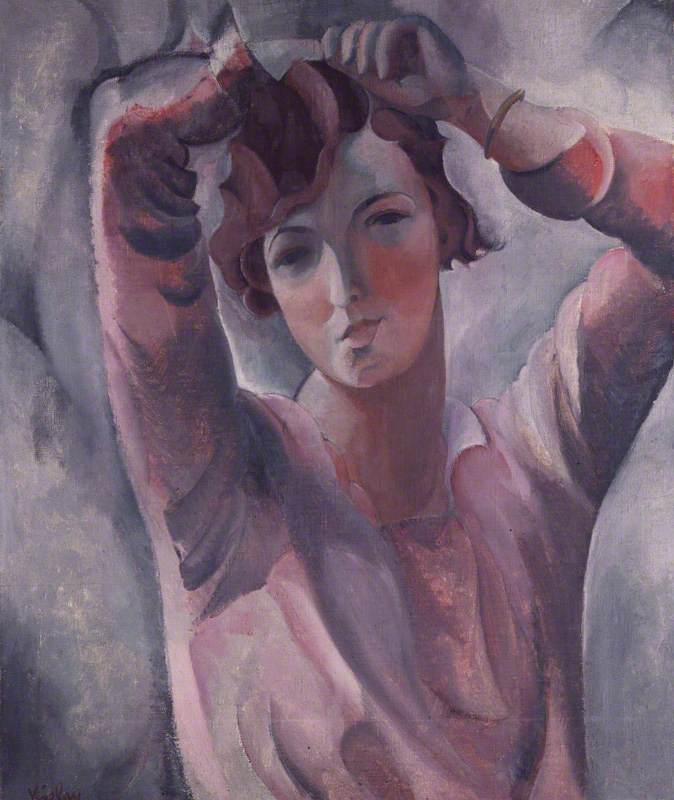

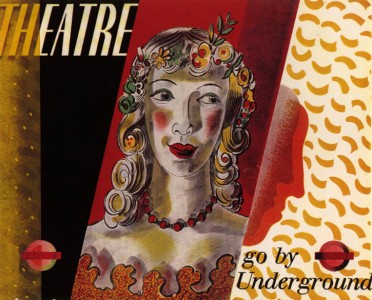

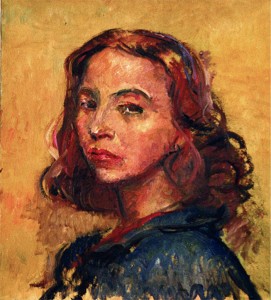

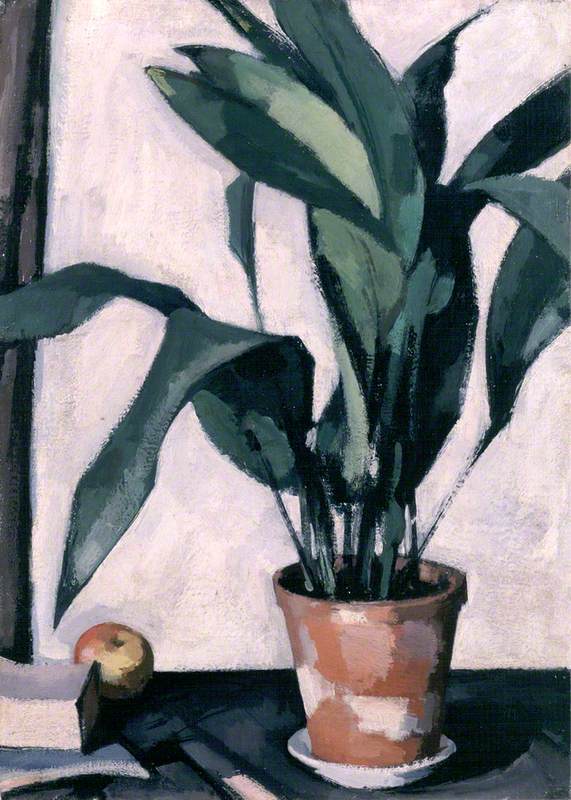

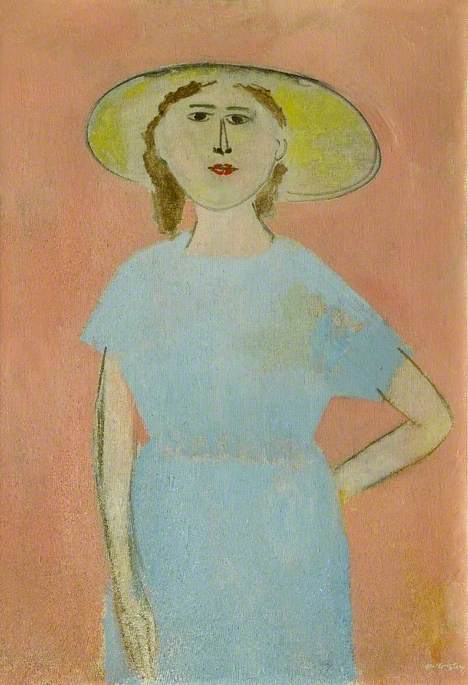

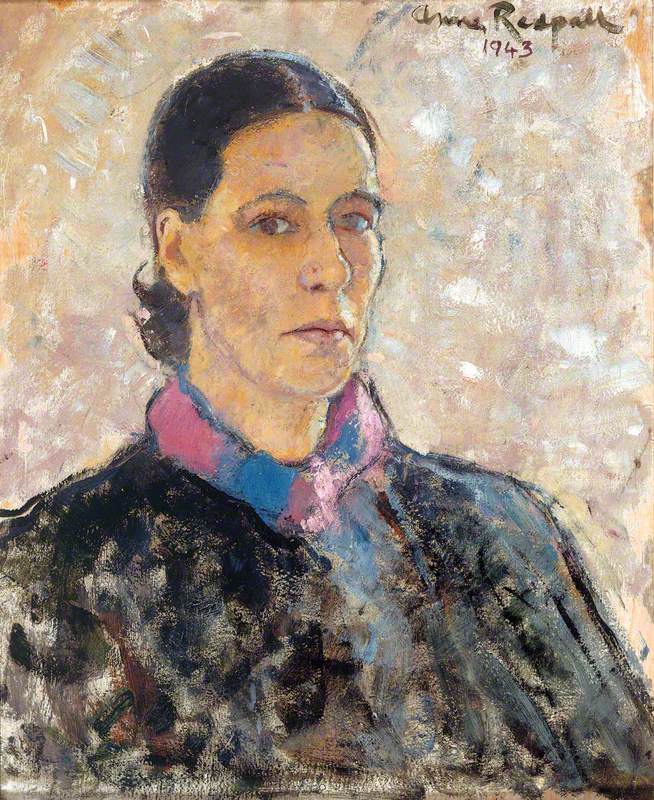

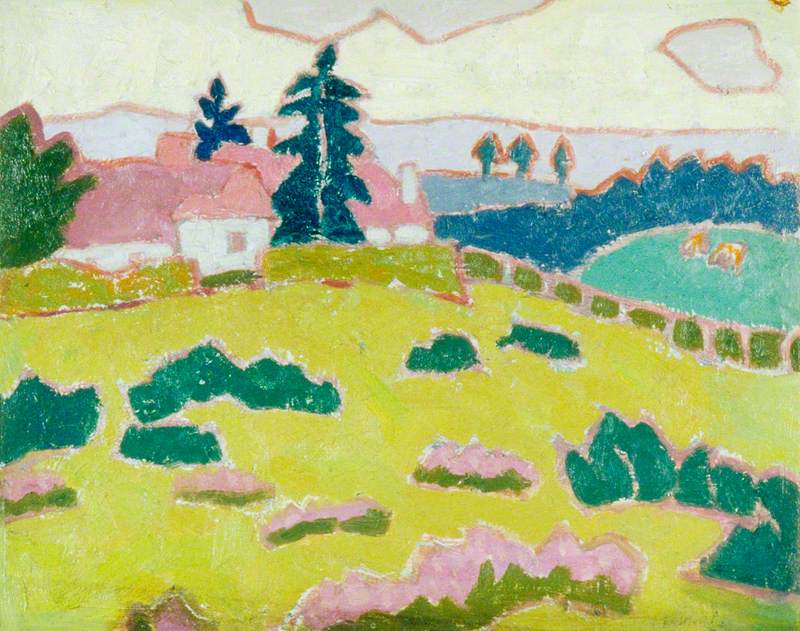

Along with other modernists, she took part in the 'rappel à l'ordre' (call to order). She had written in her poem Prelude, in 1918, 'I call the universe to order, the irregularity of phenomena is no longer supportable.' In place of fractured abstraction, Dismorr turned to portraiture and landscape. She showed at the Seven and Five Society with Winifred Nicholson and Sophie Fedorovich, and at the London Group where Paule Vézelay (1892–1984) was also exhibiting figurative work.

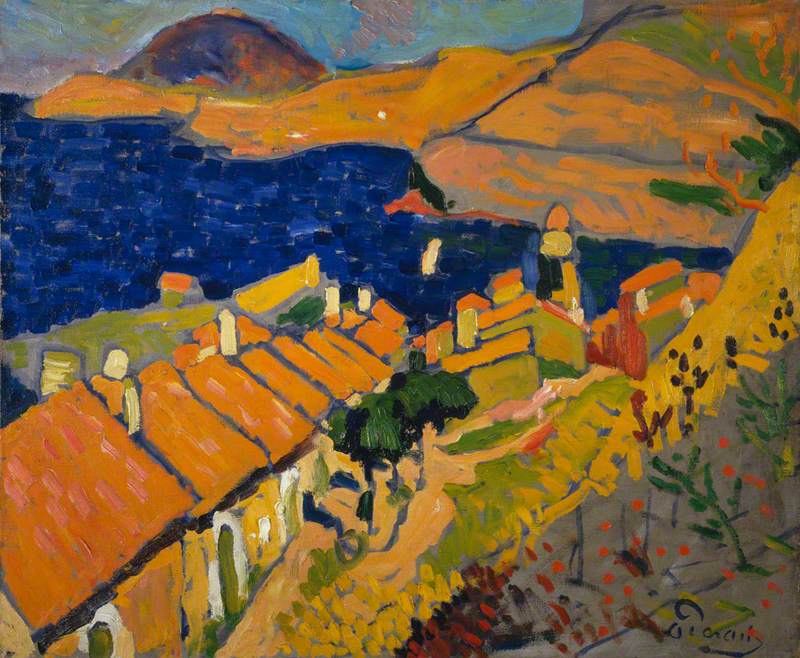

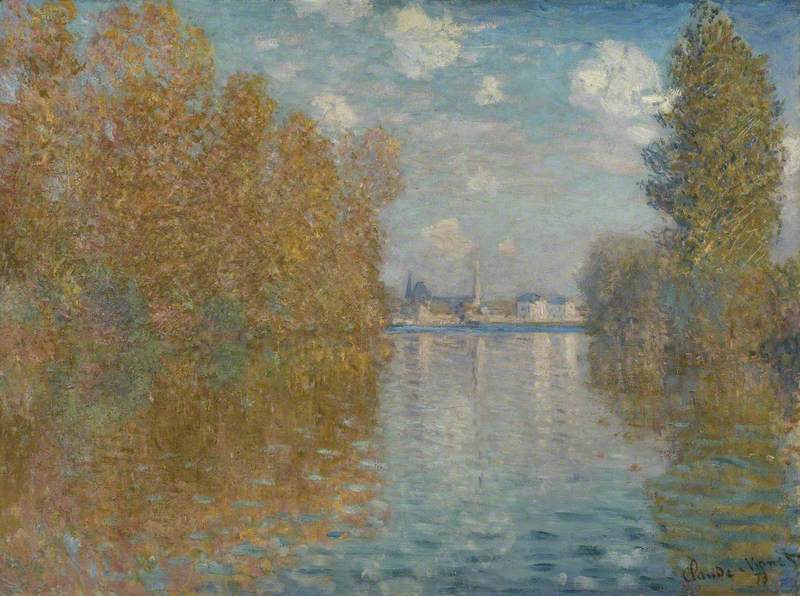

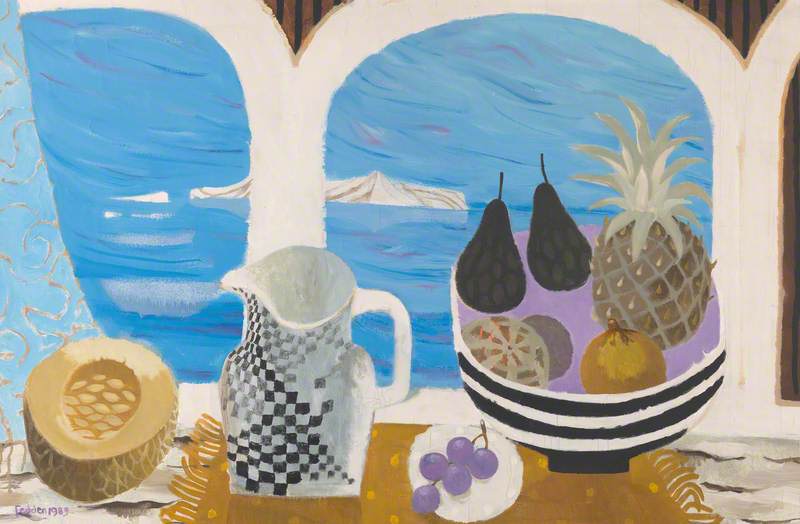

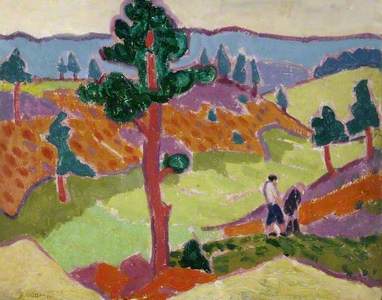

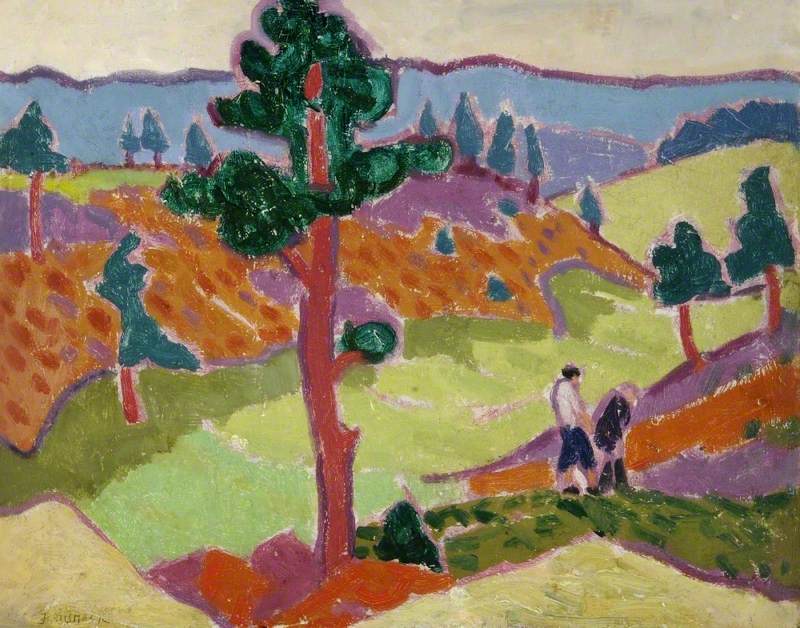

Dismorr made watercolours of female music-hall artistes, experimenting with distortions of scale, portraits of learned women friends such as the expert on ancient art, Henrietta (Yettie) Groenewegen-Frankfort, and landscapes, some of L'Estaque, a place associated with Paul Cézanne (1839–1906). It was landscapes that made up the most part of Dismorr's solo exhibition in 1925, provoking Frank Rutter's admiring review.

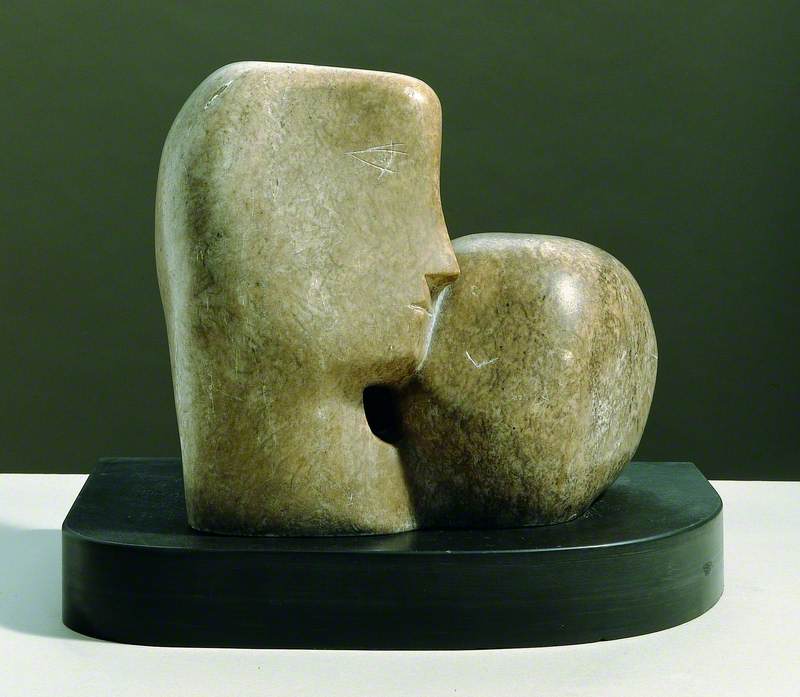

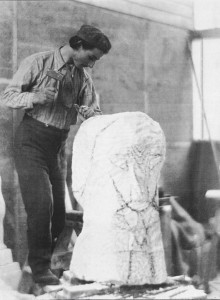

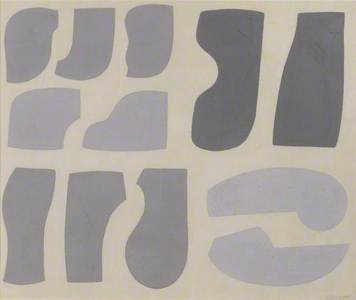

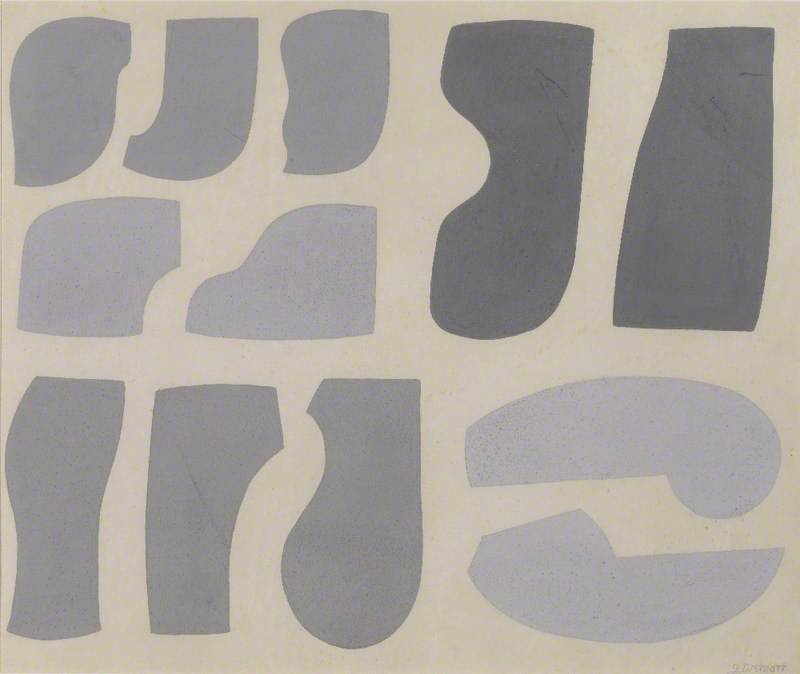

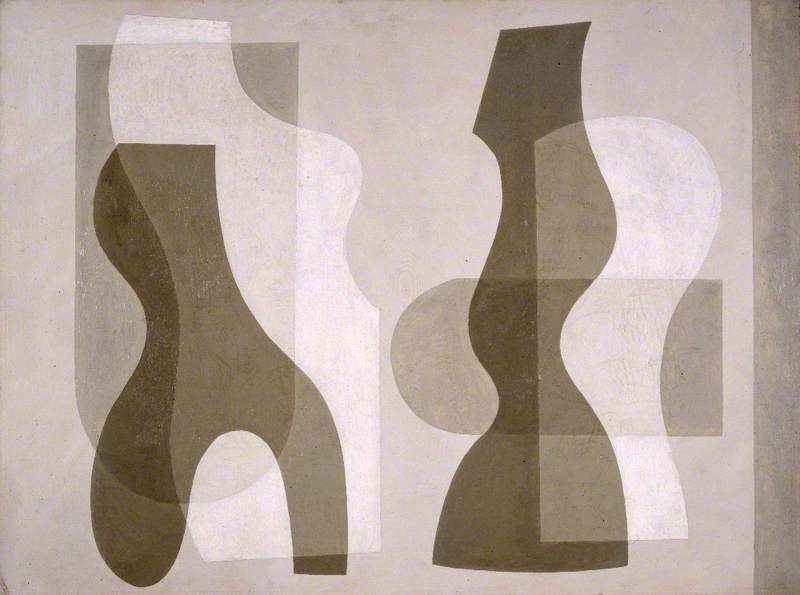

By the early 1930s, Dismorr was living in London in Putney and later, Hampstead, where the community of artists grew with the influx of refugees from Nazi Europe. Her awareness of the rising threat of fascism and alliance with those opposing it is evident in her choice of friends and exhibiting venues, her library (a list of its contents survives) and her decision to move into abstraction once more. Among her circle was the communist and surrealist poet Roger Roughton, and she showed with the anti-fascist Artists International Association alongside Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975).

Dismorr owned a book of essays by AIA members, 5 on Revolutionary Art, with a foreword by artist and AIA campaigner Betty Rea (1904–1965) and she showed, with Rea, in 'Die Olympiade onder Dictatuur', an exhibition mounted in Amsterdam in 1936 to counter Nazi cultural repression. While Dismorr's decision to no longer paint figuratively was partly motivated by formal concerns, it should also be understood in the light of her political sympathies during a period labelled by W. H. Auden the 'low dishonest decade' – a time when modernist abstraction, international and universal in ethos, was reviled by Hitler's nationalist regime.

During the last summer of peace, Dismorr's mental health collapsed once more and she killed herself aged 54. Among her papers is an untitled late fragment:

'In the embraces

Of foolish impassioned moods

I still pursue

(Their arms about my neck)

The dark, the beautiful, the austere

Moment that refuses me.'

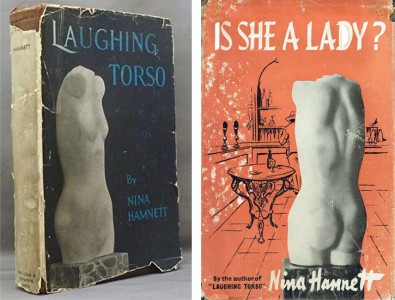

Alicia Foster, Curator of 'Radical Women: Jessica Dismorr and her contemporaries' at Pallant House Gallery from 2nd November 2019 to 23rd February 2020

.jpg)