What characterises an artist as naïve? All the best artists probably preserve something of the naïve within them; that ability to reach into their innate responses to a subject rather than skate on the surface of learned technique or received idiom. The ability to hold the freshness of the child's eye has been valued by artists at least since Paul Klee and Picasso, who liked to remark: 'It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.'

The painter Jack Jones, whose centenary is celebrated in 2022 by exhibitions in Cardiff, Swansea and Aberystwyth, was untrained as an artist and took up painting only in his 30s. He was sometimes referred to as the 'Swansea Lowry', which frustrated him as he had never heard of Lowry when he set out to paint in the early 1950s. There were similarities, which grew rather than diminished over the years, but Jones had found his own route to simple, schematic expression of what he saw. His first great inspiration had been Van Gogh.

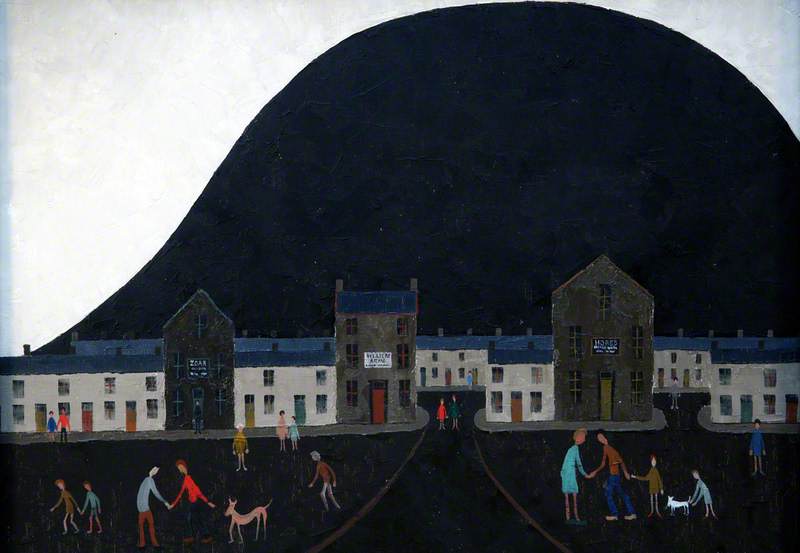

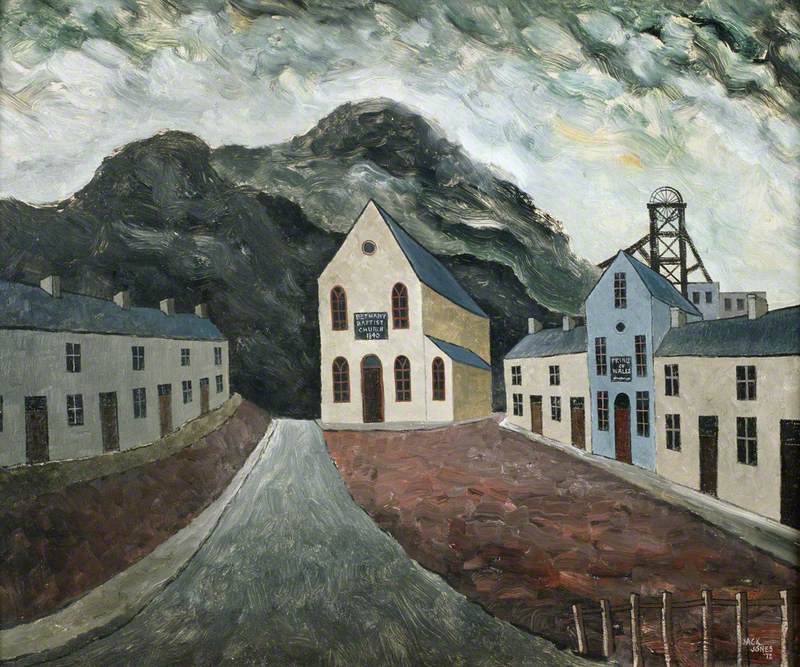

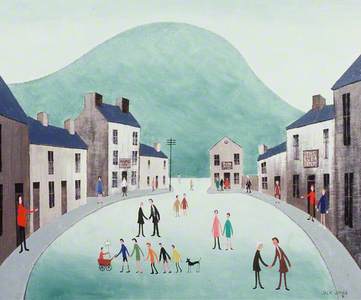

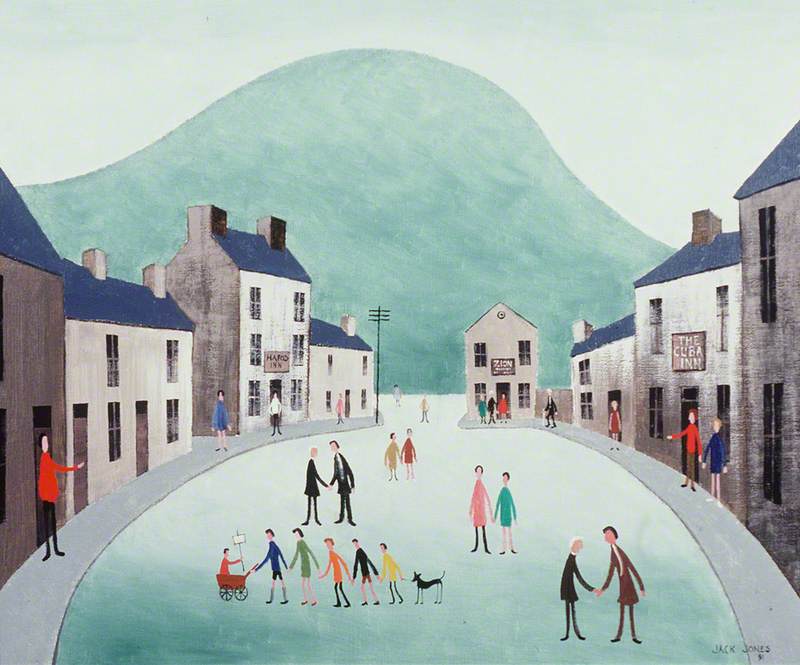

Jones became well-known for his vivid, heartfelt depictions of people and places, most famously in memory paintings of the working-class community where he grew up in pre-war Swansea. His pictures beguiled viewers with their warmth of feeling and their intensity as images, modulating warm greys and pinks with flashes of bright colour and setting them off with jet-black heaps of copper slag and moving figures. When he died in 1993, he had been a full-time painter for the last twenty years.

A vein of clear, 'child-like' painting was mined by several noted artists from the 1920s onwards, some of them genuine outsiders, like Alfred Wallis, and many faux-naïve, like Ben Nicholson, Christopher Wood and L. S. Lowry. In their industrial subject matter and style, the comparison of Jones' paintings – especially his later ones – to Lowry's was not unreasonable. Although it probably harmed him at the time, while Lowry was still perceived by many as a popular novelty, the comparison seems more flattering now that Lowry is understood to be a major artist.

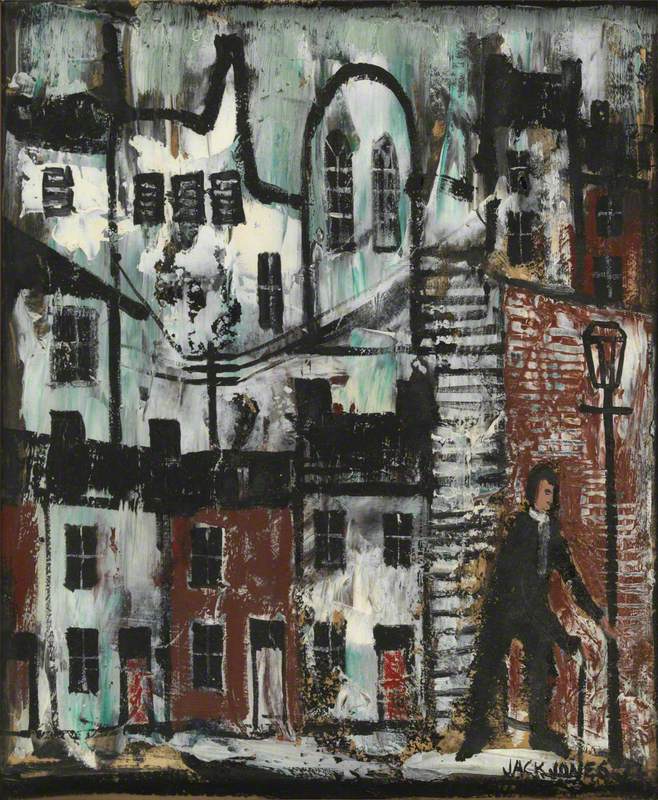

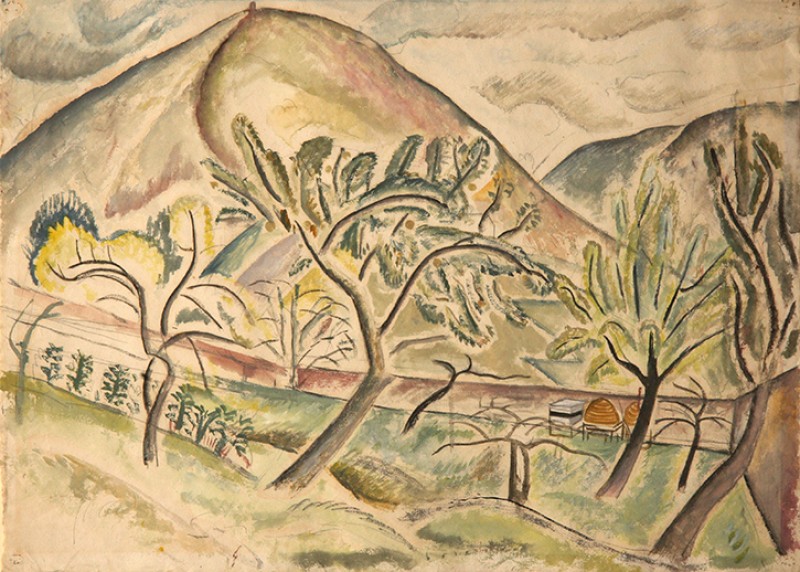

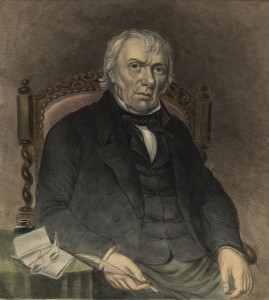

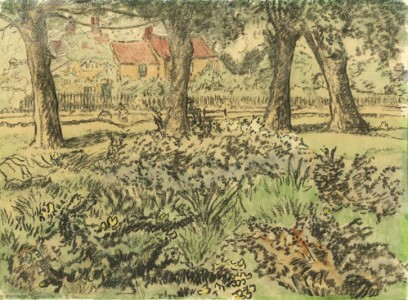

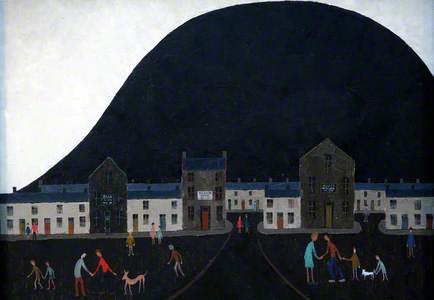

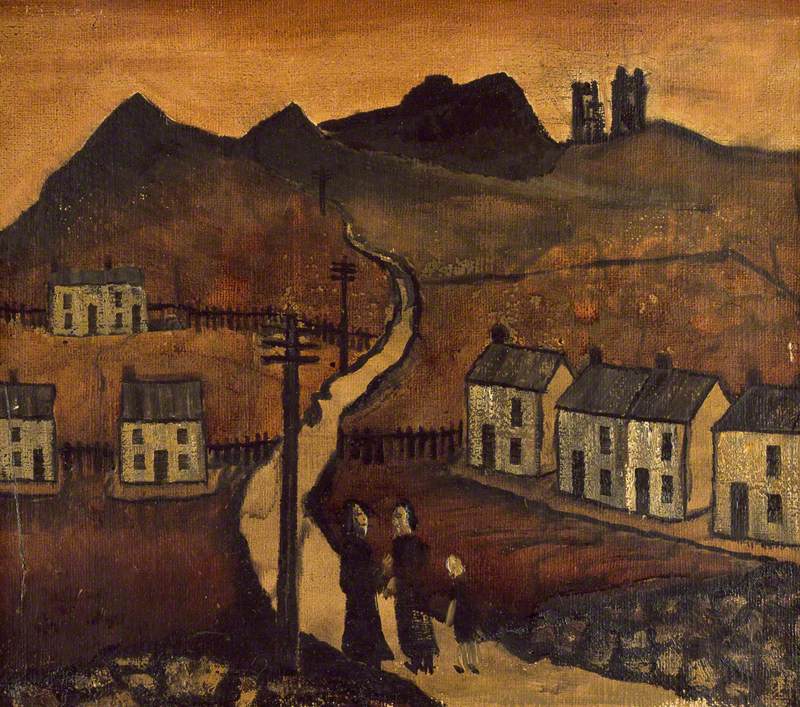

Landscape with Houses and Old Works

c.1950

Jack Jones (1922–1993)

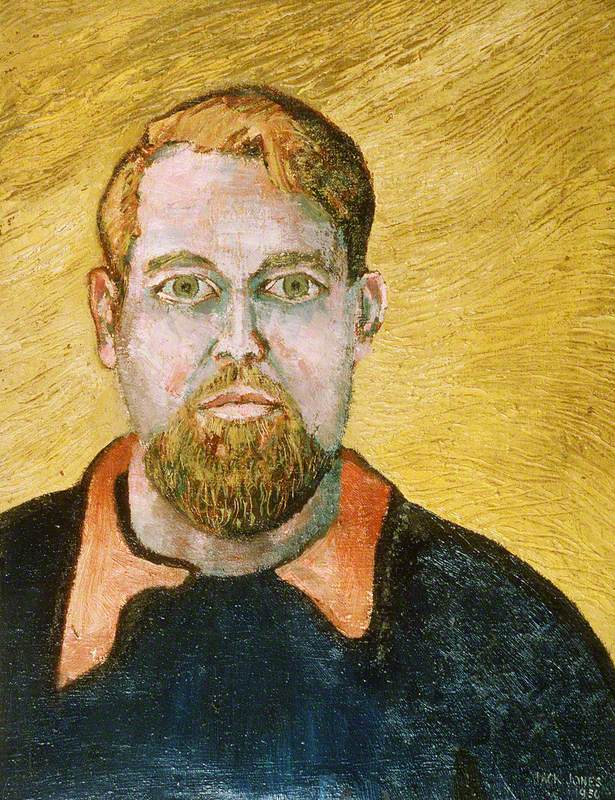

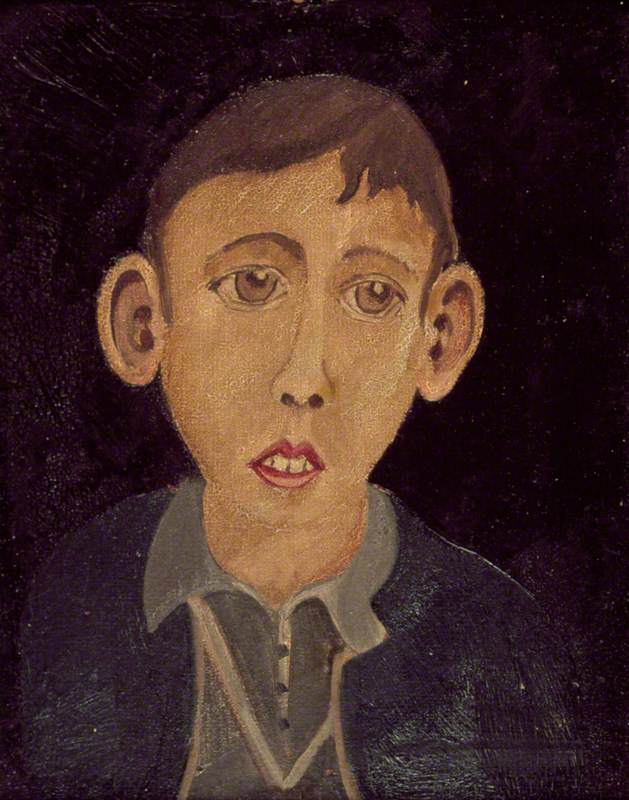

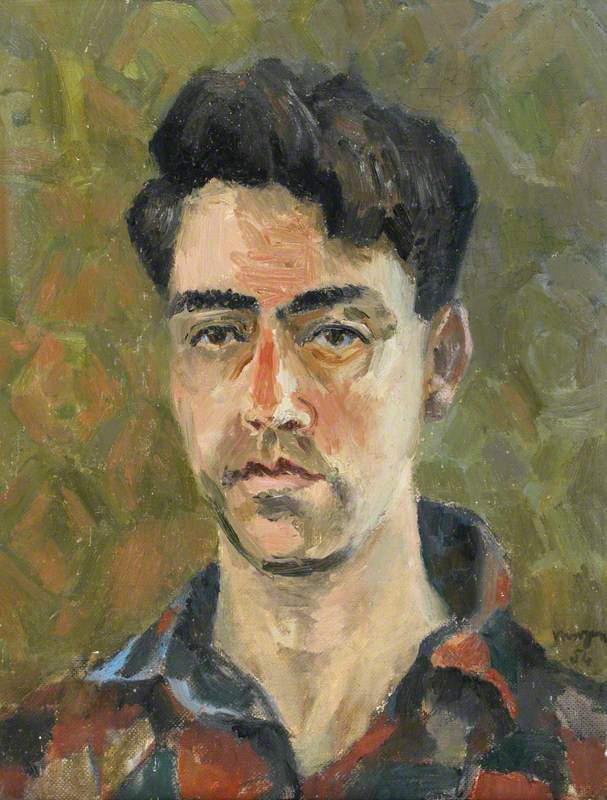

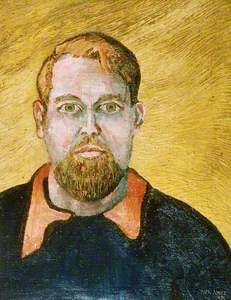

Jones' earlier paintings, like his 1950s Landscape with Houses and Old Works, which showed slag heaps and the ruin of the eighteenth-century workers' tenement known as Morris Castle, owed far more to Van Gogh or even to Morris the industrialist's descendant, Cedric Morris the painter. The same could be said of Jones' early Portrait of a Boy, which recalls Cedric Morris' use of what he called 'emotive distortion' to reveal his sitters.

Jack Jones was born in 1922 in Swansea's Hafod district, the set of streets packed tightly between copper works and waste tips that was his lifelong inspiration. Brought up by his grandmother, he learned only in his teens the family secret that he had been born illegitimate. His childhood straddled the Depression but he remembered his formative years warmly and wrote, 'in spite of the poverty and the ill-health there was a bubbling effervescence in the Hafod people that transformed them from victims to victors.'

Contrary to his challenging start in life and the untutored qualities that he found in his art, Jack Jones was highly educated. After war service in the RAF, he studied English and French at Bangor Normal College, the University of Paris and the University of Caen. Later, he taught English at schools in London, where he lived with his French wife Huguette and son Shôn.

Under the name Jack Raymond Jones he wrote poetry, journalistic interviews with well-known writers, a guide to education for parents, and radio scripts for BBC European services. When he started painting he had just published his biography of Van Gogh, The Man Who Loved the Sun.

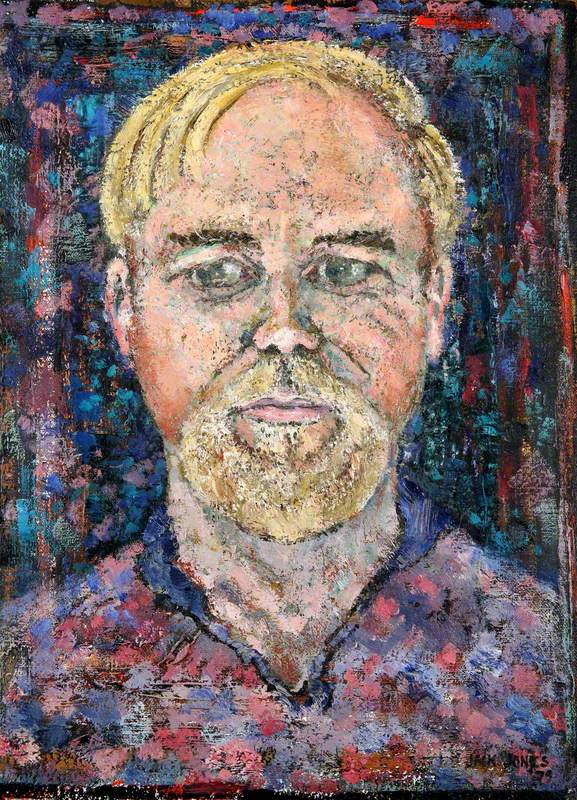

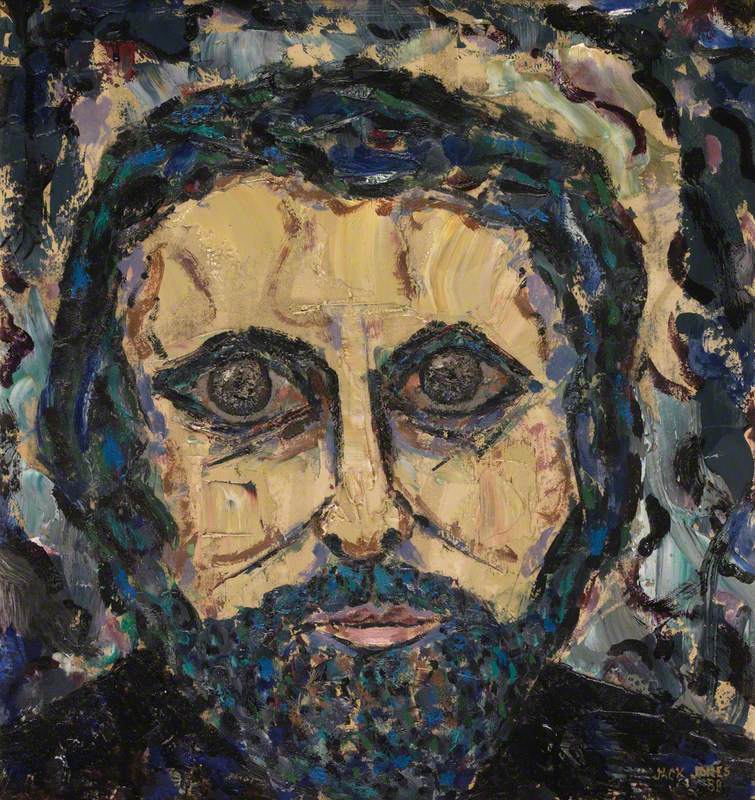

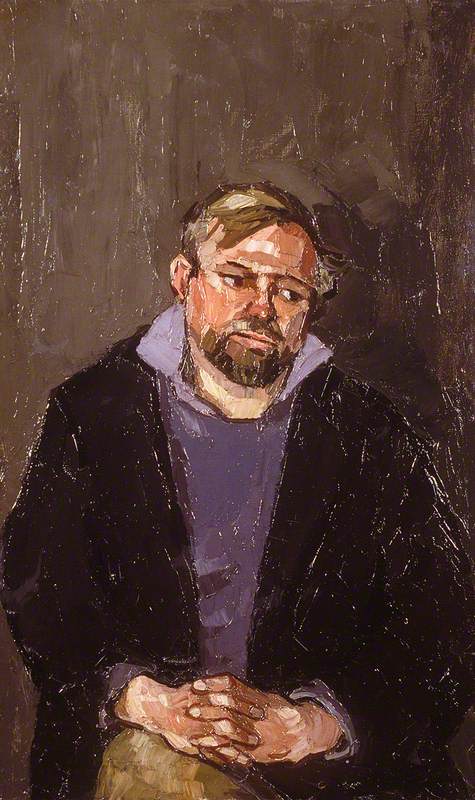

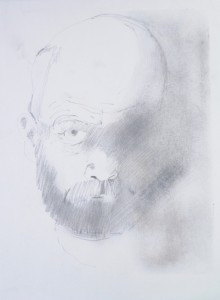

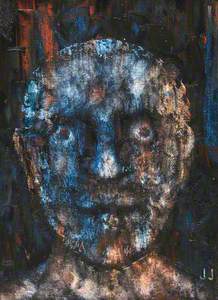

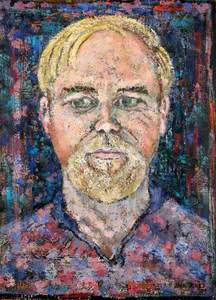

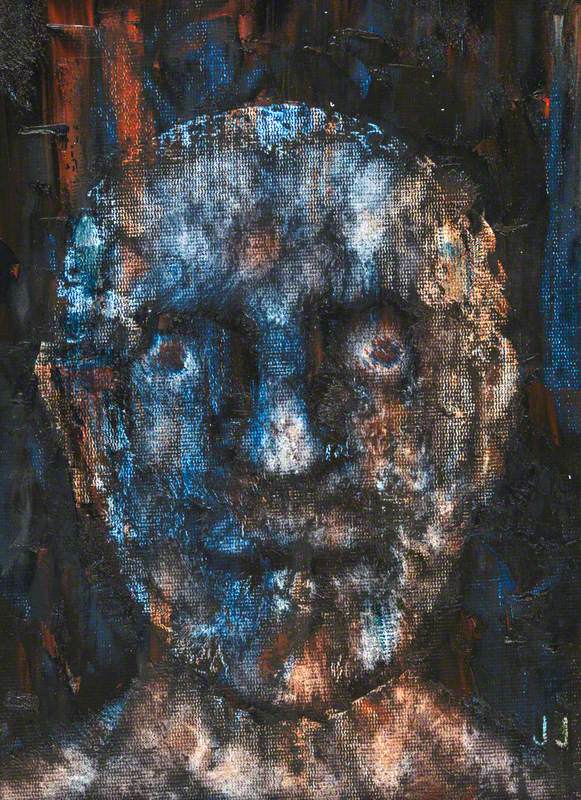

Anthony Hopkins (b.1937)

c.1980

Jack Jones (1922–1993)

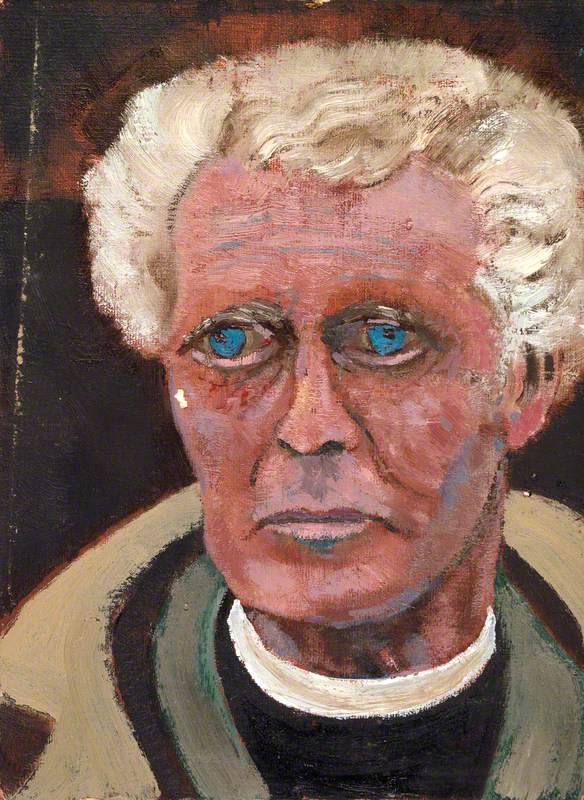

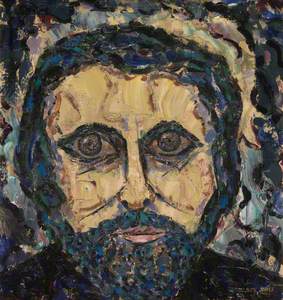

He forged many friendships through his art and journalism – among others with the actor Anthony Hopkins, the poet and filmmaker John Ormond and the artist Kyffin Williams, who recalled him as 'a jolly fellow, downing his pints at the London Welsh Rugby Club and telling wild and outrageous stories.' He was the subject of two of Kyffin's most insightful portraits, which captured his darker and more troubled nature.

I myself remember conversations with Jones when I was a teenager in Swansea in which he was passionate, argumentative, confrontational: he told me that as a resident of middle-class western Swansea, I would never understand what it was like to know the neighbours all around. It was clear that he cared greatly about art, and about art as a means to convey the truth, as he saw it, of the community that nurtured him.

Professor Tony Jones of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago said in 2000 his BBC book and television series on Welsh art, Painting the Dragon, that Jack Jones, 'boils the whole valley scene down to its essential elements.'

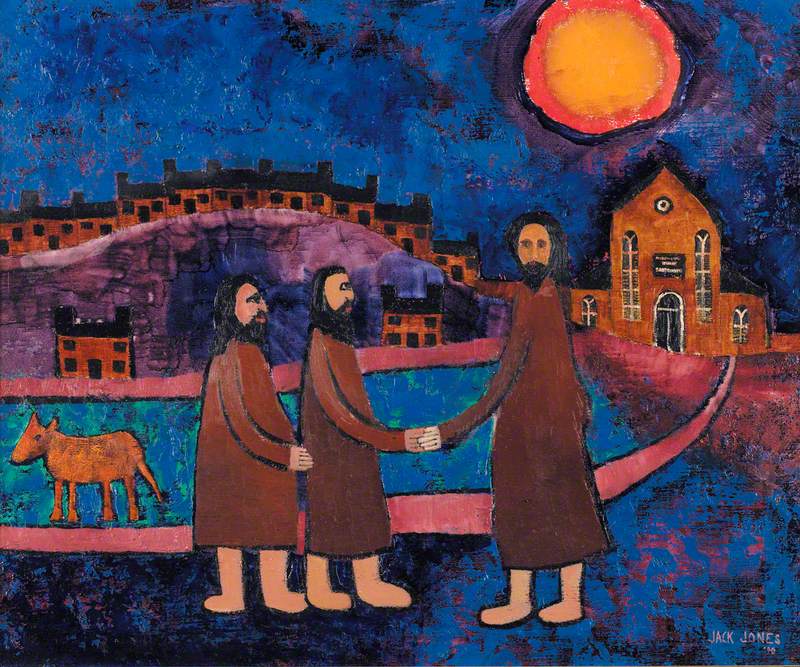

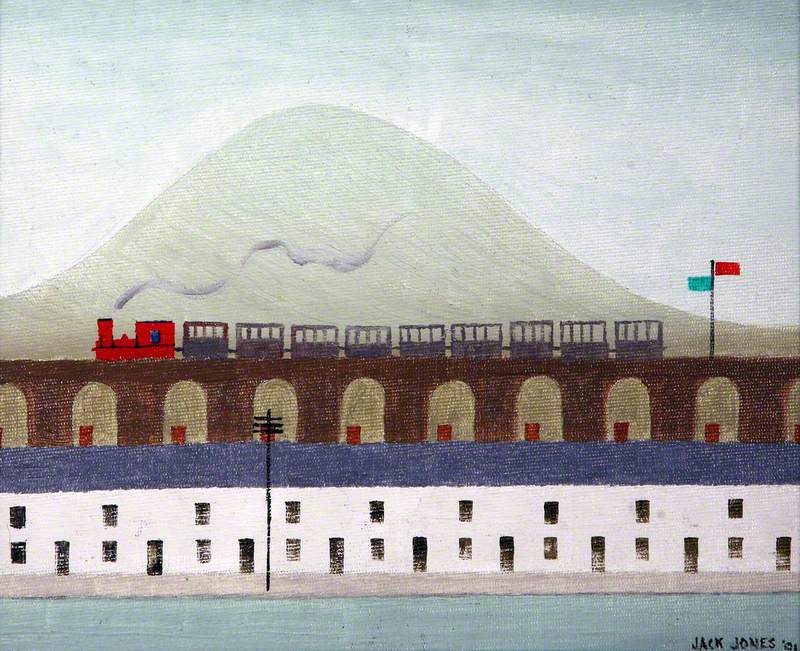

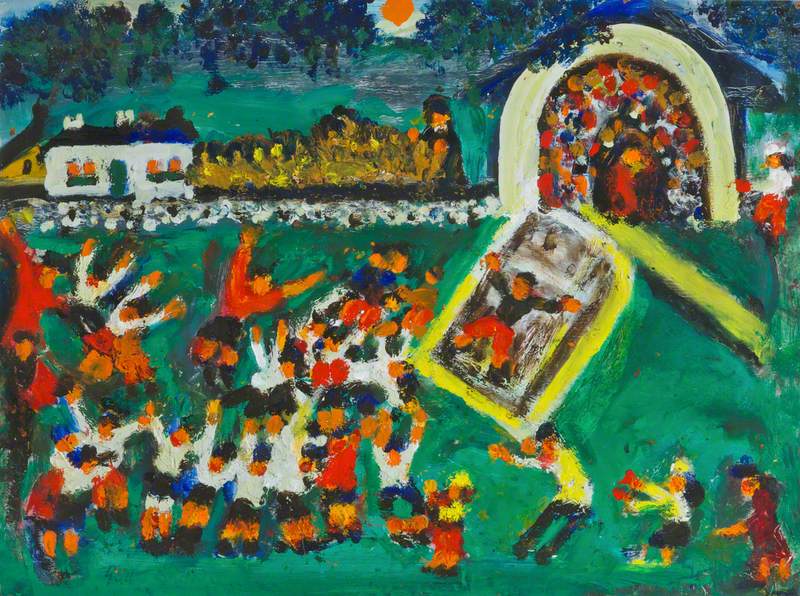

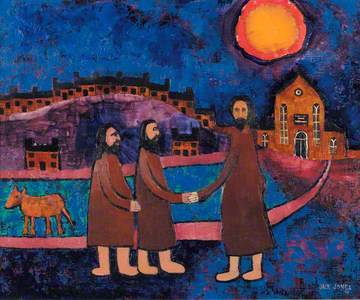

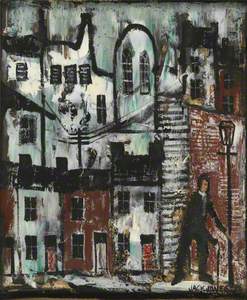

He simplified the people and the buildings: the clustered chapels (Zion, Ebenezer, Zoar, Horeb, Bethany), the Villiers pub, the rows of houses, are all shorn of detail to their essentials. The heap of copper slag from the Hafod works really did curve like a black whale over the workers' houses, but sometimes he would add a storey to a pub to show its status, enhance the railway viaduct with rounded arches instead of flat beams or move buildings where he wanted them.

He wandered from the streets of Hafod sometimes to paint new subjects – into neighbouring streets, down to the great town chapels, or occasionally even further, to the mills of Yorkshire or the streets of Paris. After a heart attack, he left teaching and returned to live in Swansea, where he gave all his time to painting.

Hafod Inn, Cuba Inn and Zion

1991

Jack Jones (1922–1993)

Finally, he moved back to London, dying just as a major exhibition of his work was opening at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in Swansea.

Many qualities of the inter-war community he pictured have changed beyond recognition in the century since he was born: some of the terraces have been cleared for urban renewal or road widening; pubs and chapels have closed; cars fill the streets where children played; the reclaimed tip is now a school. But Jack Jones' paintings survive to speak for what they were and state in images the proverb, 'It takes a village to raise a child'.

Peter Wakelin, writer and curator

Jack Jones' papers and many paintings are held in the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth, a selection of which are showing there throughout spring 2022. Another small display is at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in Swansea from 8th April to 11th September 2022. The Jack Jones centenary exhibition is at the Martin Tinney Gallery in Cardiff from 11th May to 1st June 2022.