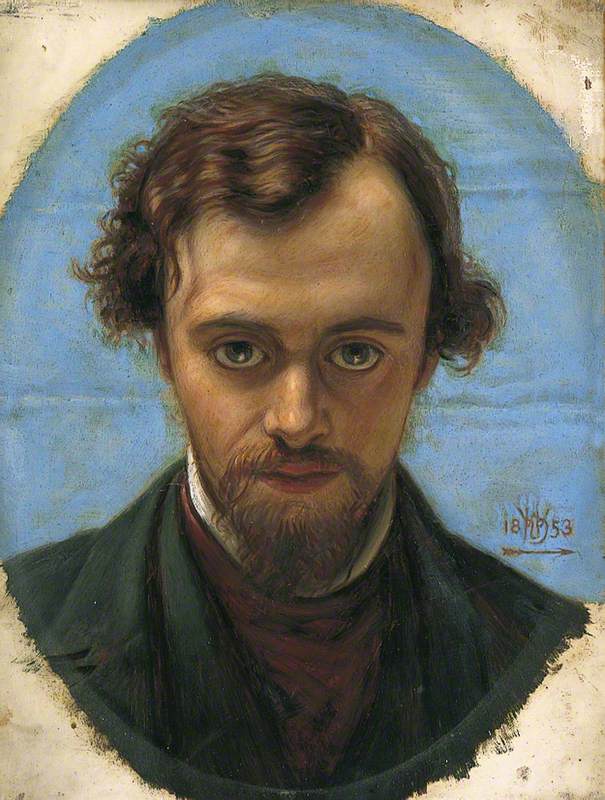

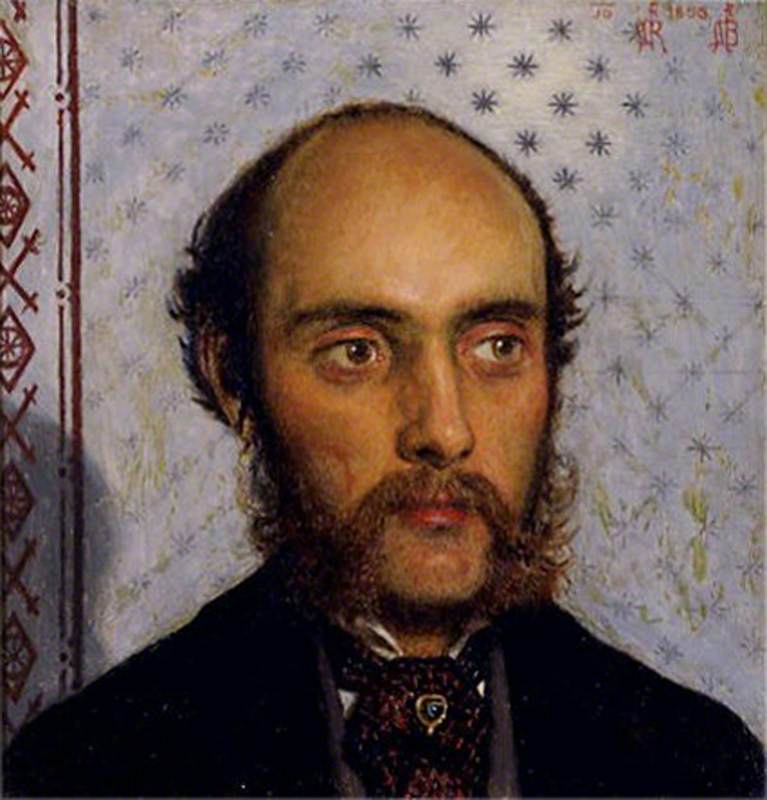

The first drawing by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893) to enter the collection at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery was his large pastel Portrait of Miss Iza Duffus Hardy, 1872.

Portrait of Miss Iza Duffus Hardy

1872, pastel & chalk on brown paper by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893)

This was donated in 1903 by the painter and art connoisseur Charles Fairfax Murray, who is thought to have purchased it in a sale of Brown's effects following the latter's death in 1893. By 1904, the Birmingham Museum had raised enough subscriptions to purchase 800 more Pre-Raphaelite drawings from Murray's fine collection.

Originally trained as a technical draughtsman, Murray became a protégé of John Ruskin and was taken up by the Pre-Raphaelites, working in the studios of Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris (of whom he made several portraits) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Murray copied Rossetti's painting of Morris's wife Jane when it came to him for repair).

Water Willow

(after Dante Gabriel Rossetti) 1893

Charles Fairfax Murray (1849–1919)

Murray became very much a part of their circle and a keen collector of their work.

Madox Brown's serious, if not brooding, portrait of Hardy gives few clues as to the life of the sitter, although it is likely that Murray knew or had met her. The Hardys were close friends with the Browns, as they were the Rossettis.

William Michael Rossetti, who was married to Brown's eldest daughter Lucy, wrote in his Reminiscenes (1906) that both Mrs Hardy and her daughter were 'warmly attached to my wife'.

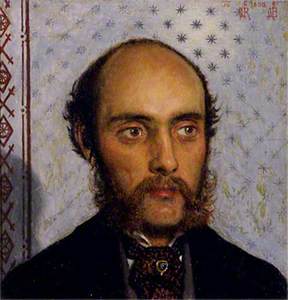

William Michael Rossetti (1829–1919), by Lamplight

1856

Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893)

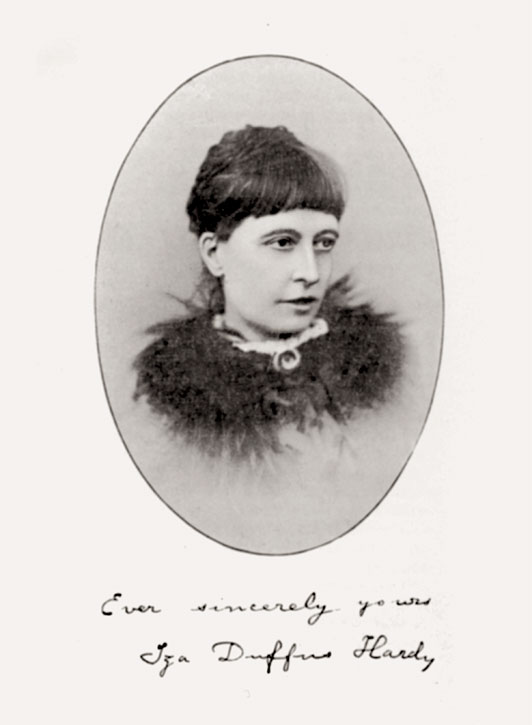

Iza Duffus Hardy, given to wearing floral silk, Liberty tea gowns, and coiling her chestnut hair in braids around her head, seems to have been an altogether livelier young woman than Brown's demure portrait might suggest.

Born in Enfield in 1850, she was the only daughter of the antiquarian Sir Thomas Duffus Hardy (1804–1878), Deputy Keeper of the Public Record Office, and his second wife, Lady Hardy. Iza was largely home-educated, concluding that she had 'learned more from my father than from all my teachers put together'.

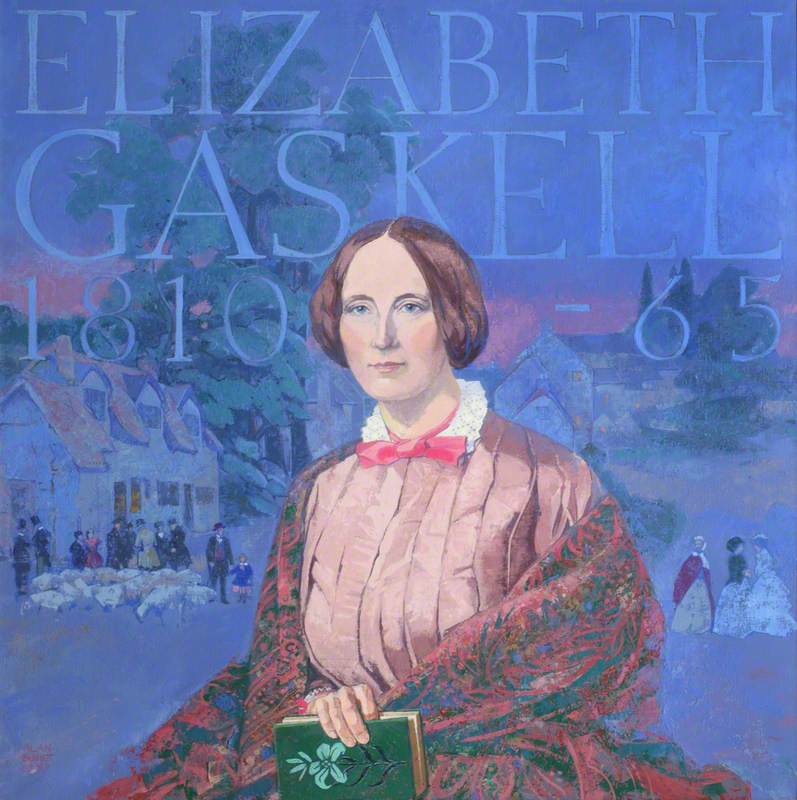

Lady Hardy (née Mary Anne MacDowell, 1824–1891) was a popular writer of romances and travel books who published sometimes under the name of 'Addlestone Hill'.

Like her mother, Iza became a prolific and popular novelist and – equally – one now largely forgotten. But they still found time to enjoy a busy social life, moving in exalted circles between Belgravia and Bohemia, with whom their Saturday evening 'At Homes' were always popular. Such entertaining was no doubt fostered by Sir Thomas who maintained that 'the busiest people have ever the most leisure', spending much time himself in the company of friends.

Though Iza expressed an early interest in becoming a sculptor, by the time she was 15 she had begun writing her first novel, Not Easily Jealous, which was published in 1872, the same year as Brown's portrait. Between then and 1910, she would publish more than 30 books, and many more short stories in the illustrated monthlies like The Strand Magazine, London Society and Belgravia.

She generally worked from 10am till 1pm every day, in what she called her 'cabin' – a small room at the back of the house she shared with her mother in Portsdown Road, Maida Vale. Iza's method was to have her stories fully planned out before she began writing, she said, adding:

'I often alter details as I go on, but never depart from the main lines. My usual way of making a plot is to build up on and around the principal situation... Having got the characters formed, and the foundation of the story laid, I build up the superstructure just as an artist would first get in the outline of his central group in the foreground, and then sketch out the background and the details.'

Interior, Woman Reading to an Old Man

1889

Frank Stanley Ogilvie (1858–1937) (after)

Iza Hardy's well-crafted but dense and highly charged melodramas, with titles like A Broken Faith, A Woman's Loyalty and The Girl he did not Marry, were liberally sprinkled with epigraphs by her friends, Rossetti, Browning, Morris and Swinburne. They were exactly of the sort serialised in the journals that George Orwell described in Coming Up For Air:

'Mother was a slow reader and believed in getting her threepennyworth out of Hilda's Home Companion. Sitting in the old yellow armchair beside the hearth, with her feet on the iron fender and the little pot of strong tea stewing on the hob, she'd work her way steadily from cover to cover...'

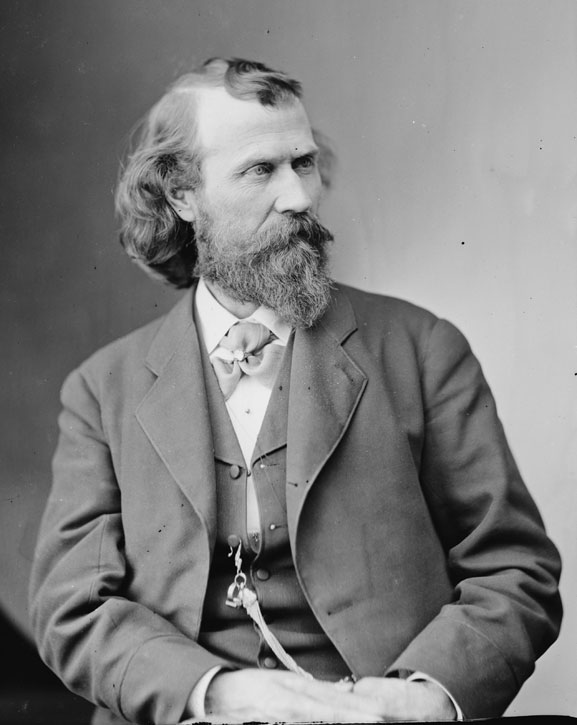

In May 1873, the year after Brown painted his portrait, Iza, then aged 23, became engaged to the American poet Joaquin Miller (1837–1913).

Joaquin Miller (Cincinnatus Hiner Miller)

c.1875, albumen silver print by unknown artist, from the Brady-Handy photograph collection

Miller, arriving in London in 1870 was a Whitmanesque 'frontiersman' of the type beloved in the London salons. Trollope hosted a dinner in his name and Miller attended the Hardys' 'Saturday Evenings' in St John's Wood in the company of Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), who was in London on a lecture tour.

Charles Warren Stoddard, then briefly working for Clemens as his secretary, complained of having to play up to the Wild West stereotype with their endless 'bear stories':

'We chat as well as an American is expected to do under the circumstance; we talk dirk and gulch and wild wide West, because this is the sort of thing we are bullied into by bevies of London maids who have never heard anything better of California.'

Miller, however, clearly relished the role. In fact, shortly before leaving America he had adopted the forename 'Joaquin' (after Joaquin Murrieta, a Mexican bandit of the Californian Gold Rush) as more fitting for a former horse-dealer from the outbacks of Liberty, Indiana, than his own, which was Cincinnatus.

Iza Duffus Hardy

1893, photograph by Russell and Sons, from Helen C. Black's 'Women Authors of the Day, Glasgow', David Brice and Son, 1893

If Joaquin Miller was a buckskin-wearing poet on the make, and an unabashed poseur, he was also a notorious womaniser.

Once married to Sutatot Shasta, a Mcleod Indian woman (with whom he fathered a child), he was only recently divorced from the poet Minnie Myrtle (with whom he'd fathered three more).

No doubt Iza Hardy had a lucky escape: by November 1873 their engagement was broken off. Miller headed off to Rome to find solace, temporarily, in the company of an Italian countess, before embarking on an affair with newly married New York society hostess Mrs Frank Leslie, who was still honeymooning with her new husband, the well-known illustrator and publisher of many journals.

William Michael Rossetti recorded in his diary of 18th May 1878, following an evening at Lady Hardy's, that she had praised Miller for his 'noble spirit in releasing Miss Hardy from any sort of engagement to him arising out of past love-passages'.

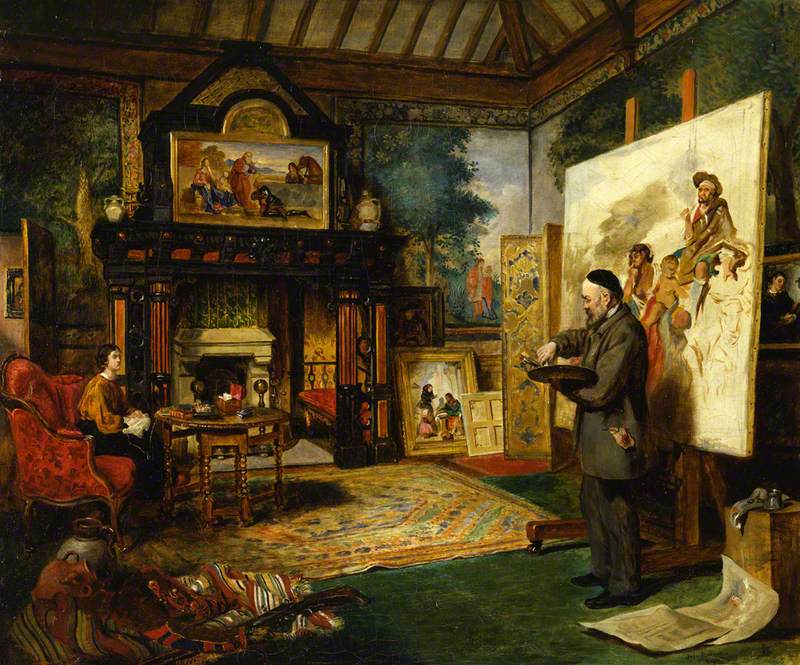

If the romance sounds like meat for one of Miss Hardy's melodramas, indeed it was. Miller was closely modelled as the inspiration for the reckless Republican Julius Lusada in Iza's 1877 novel Only a Love-Story, and a quote from his Songs of the Sierras (1871) opens one chapter of the book. It includes a Bohemian masquerade ball, and a portrait-sitting for an academic painter whose bustling studio is equipped with derelict lay-figures, skulls, props and leopard skins on the polished wood floors.

A bevy of friends and admirers, no doubt inconducive to work, come and go freely, offering criticism and entertainments, in the manner portrayed by Charles Martin Hardie and Carl Friedrich Heinrich Werner. Such scenes were drawn from Iza's familiarity with artistic and literary circles, and her own recent experiences in sitting for Ford Madox Brown.

After Sir Thomas's death, in the early 1880s, Iza and her mother made two trips to America and Canada. Iza produced two accounts of her travels: Between Two Oceans: or, sketches of American Travel (1884) and Oranges and Alligators: sketches of South Florida life (1886). In the first, Iza vividly described their departure:

'Our big ship stretched ins lazy length sleepily across the sluggish, dark waters of the Mersey... Half an hour of hubbub, seeking State-Rooms, settling baggage, shouting for stewards, saying last words...A few minutes more and the Babel of farewells and au revoirs, the kissings, and huggings, and shaking of hands, are all over; the tender is swaying away from the crowded bulwarks, white handkerchiefs are waved, and hands are kissed... Now practical spirits go down to their cabins...; sentimental ones linger on deck to watch 'the last of England'...'

No doubt Iza had in mind Brown's famous painting of 1855, which used his own wife Emma as the model (and whose face Brown's later portrait of Iza brings to mind).

In America, they became acquainted with, among others, the poets Oliver Wendell Holmes and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Miller presented himself early on in the first trip, but William Rossetti noted that Miller was warned he might enjoy 'only the usual friendliness'; in fact, Mrs Hardy had taken pains to ascertain that Miller had recently remarried, as he had, to his hard-done-by third wife, Abigail Leland, in 1879.

In America, the Hardys moved in the highest society, rubbing shoulders at 'musicales' with Oscar Wilde, then also touring America, and hosting parties with the newly widowed Mrs Frank Leslie, who had legally taken over her husband's name and his businesses.

Miriam Florence Folline Leslie

1893, photograph by unknown artist. From Frances E. Willard and Mary A. R. Livermore's 'A Woman of the Century', 1893

She would incorporate many aspects of these travels into her novels: The Love that He Passed By (1884) recreates the Californian valleys. and Love in Idleness: the story of a winter in Florida (1887) is set among its orange groves.

The inspiration for Iza's novels was also drawn from newspapers, or from the accounts of fellow travellers, or like A New Othello, a combination of both.

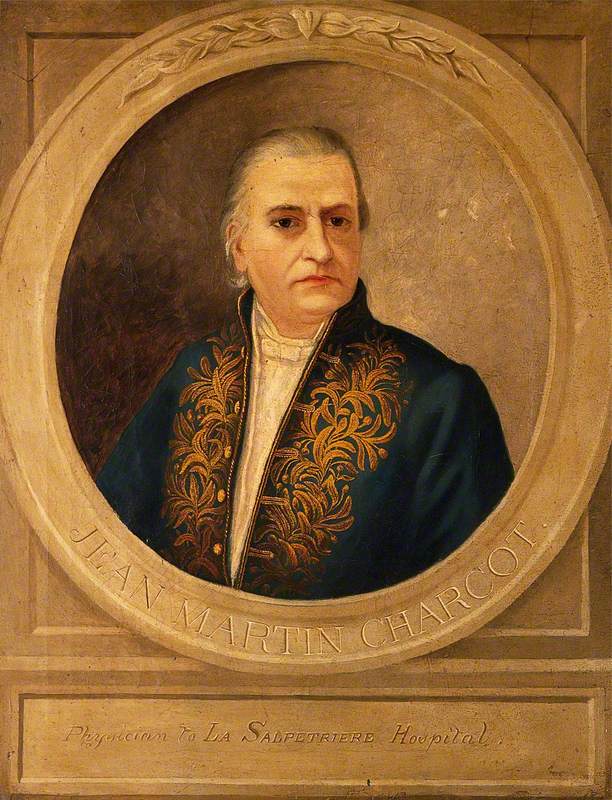

This latter book, published in 1890, was based on her research into the hypnotic experiments of the renowned Dr Charcot, whose demonstrations at Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris had such a profound impact on the young Sigmund Freud; as well as the first-hand experience of a Dr Morton (possibly Dr Morton Prince?) whom Iza had met on their travels.

Iza at her writing desk

illustration by an unknown artist, from 'The Strand Magazine', no. 29, May 1893

After the death of her mother, Iza Hardy made several further trips to the United States, in 1896 and again in the 1900s. She continued to enjoy the friendships of many fellow authors and artists – including Joaquin Miller, with whom she remained on friendly terms throughout her life. But her personal life remained always rather private, and she never married, dying in a nursing home in 1922.

Sara Ayad, independent art researcher