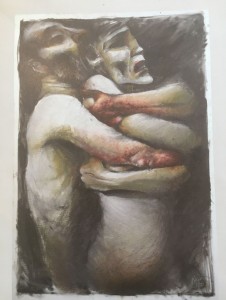

When did you last see a piece of visual art inspired by music, a poem, a play or a book? Perhaps not as often as you might expect. But literature, theatre, and music have been an endless source of material for artistic interpretation.

While some modern and contemporary artists draw upon text, folk tales, myth and music to fuel their work, paintings and sculptures inspired by other art forms reached a zenith in the nineteenth century and perhaps represent something of a lost genre – outside of illustration and fan art today.

The Guildhall Art Gallery's collection of paintings, drawings and sculpture, contains many examples of works inspired by stories, lyrics, songs and those who create them. It is from this extensive collection – over 400 years of art – that the current exhibition 'Inspired! Art inspired by literature, theatre, and music' is drawn, with additions from the City of London collections at Mansion House (Dutch and Flemish paintings of the seventeenth century), and Keats House museum. The exhibition explores the wide variety of influences and different ways artists have been inspired by other cultural forms to reveal the vital interrelation between the Arts.

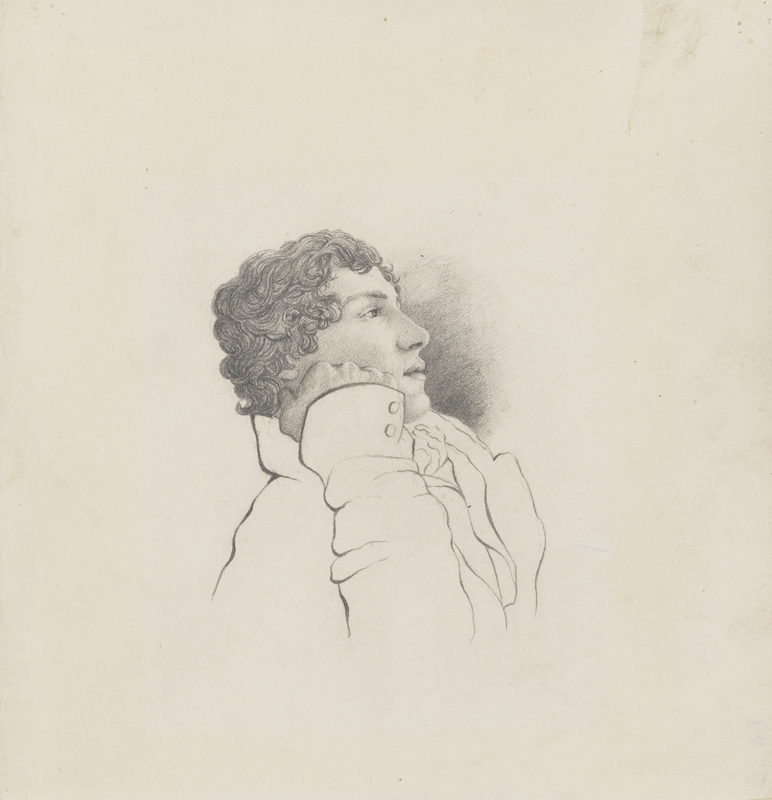

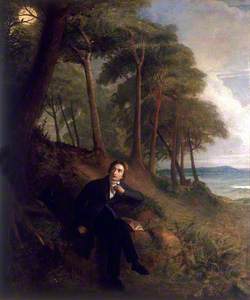

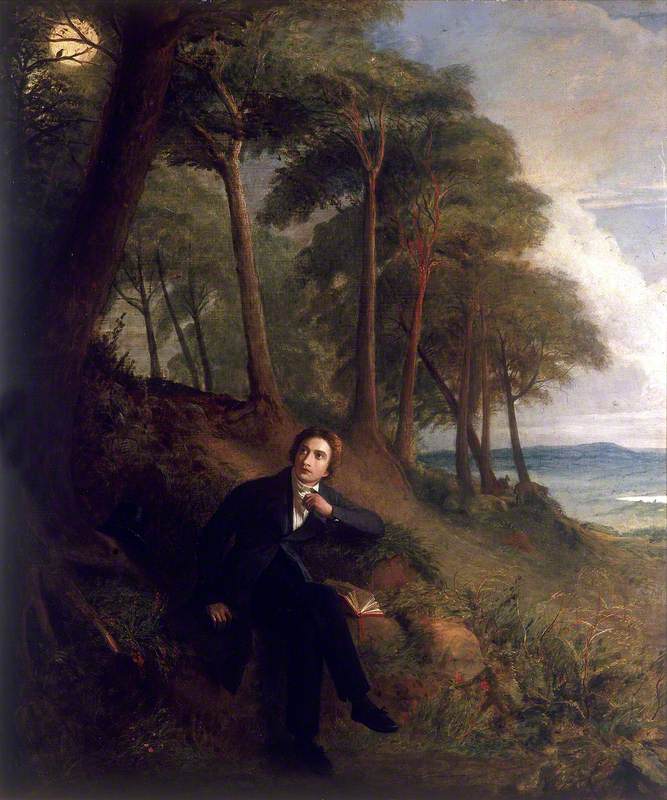

Keats Listening to a Nightingale on Hampstead Heath

1845

Joseph Severn (1793–1879)

The works here are often intertextual and inspire other interpretations themselves. Often you will see inspirations of inspirations. The curated selection pays particular attention to Victorian works, which demonstrate a substantial preoccupation with literary source materials commonly understood by an educated middle-class audience.

However, in an age of increased literacy and education, widening access to art and culture through public galleries, the proliferation of publishing and a burgeoning theatrical scene, visual art that referenced text and performance was more popular than ever before.

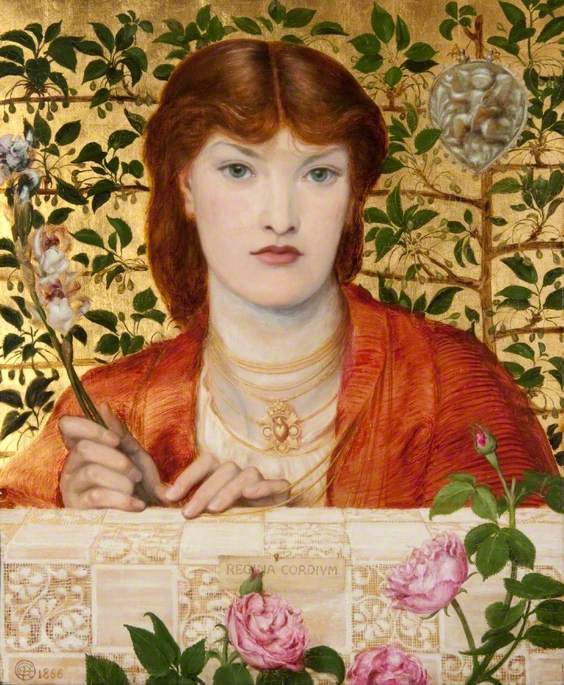

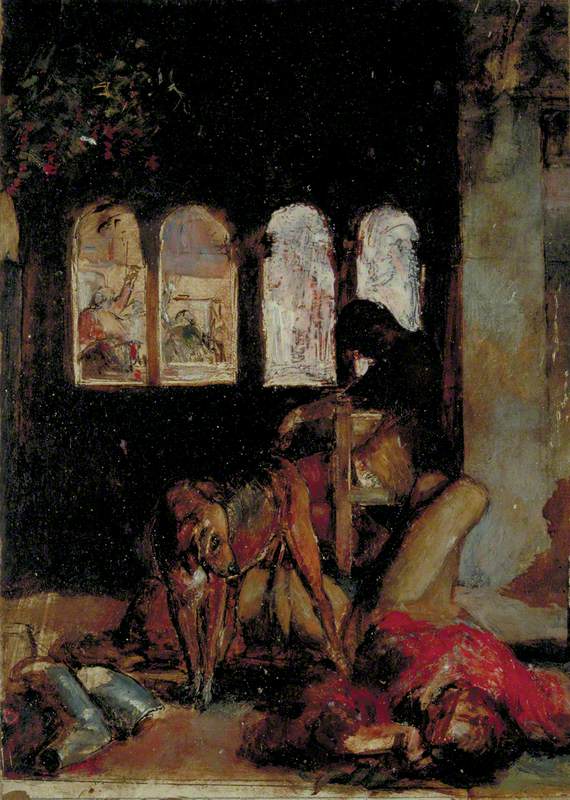

The Pre-Raphaelites were strong proponents of visualising poetry in painting, particularly in reviving the work of John Keats in the decades following his untimely death. William Holman Hunt's first academy painting (with details added by John Everett Millais), The Eve of Saint Agnes (1848), can be seen up close along with rarely seen pencil and oil sketches which reveal his process of figurative construction.

Study for 'The Eve of Saint Agnes'

c.1847–1848

William Holman Hunt (1827–1910)

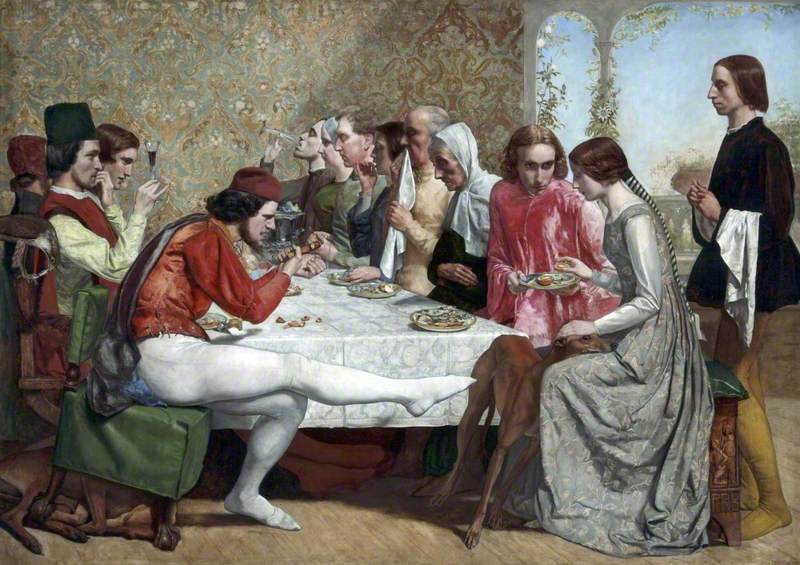

Millais' own depiction from Keats' Isabella and the Pot of Basil (first published in 1818, and itself based on a tale from Boccaccio's fourteenth-century Decameron) can be seen in watercolour form – a cabinet-sized artist's copy of the large oil held at Walker Art Gallery.

Indeed, the Pre-Raphaelites' own poetic forays go on to be sources of inspiration to later generation Pre-Raphaelites and aestheticists towards the turn of the century. John Byam Liston Shaw's intensely colourful depiction of Rossetti's Blessed Damozel comes 45 years after the poem was first published in The Germ in 1850, and contains an excerpt from the poem on the canvas to leave viewers in no doubt as to its source.

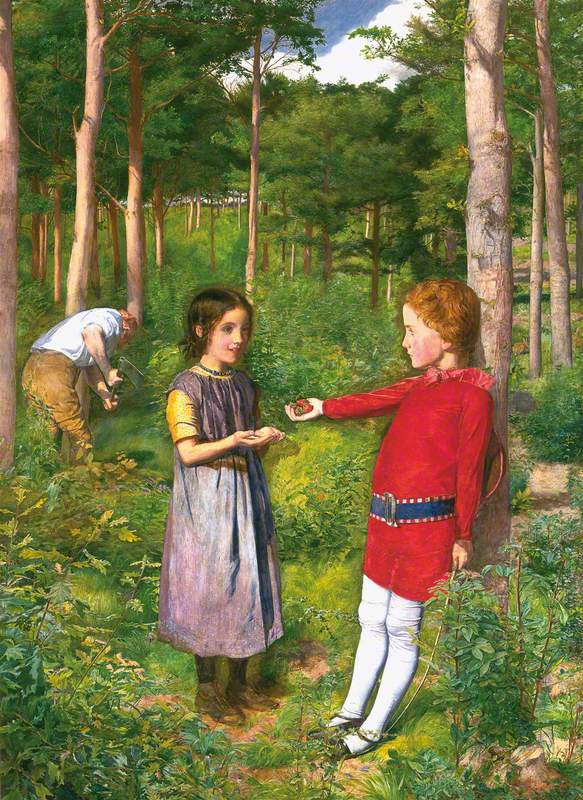

Direct referencing of text was common practice for those working in this genre – and often works of fine art follow contemporary literature very swiftly. Millais' scene from Coventry Patmore's Woodman's Daughter (poem published in 1844, painting debuted in 1851) was displayed with two stanzas of the poem. In this way, the artistic and intellectual cliques of the day sustained themselves, each feeding off the other.

These pieces are aimed at an audience with a shared understanding of cultural references, some of which endured, and some which did not. Don Quixote is a favourite topic, and the ubiquity of Shakespeare endures. But which of us now understands references to the eighteenth-century French picaresque novel Gil Blas; or the opera Mignon and the Goethe story it is based on?

The Banquet Scene in Shakespeare's 'Macbeth'

1840

Daniel Maclise (1806–1870)

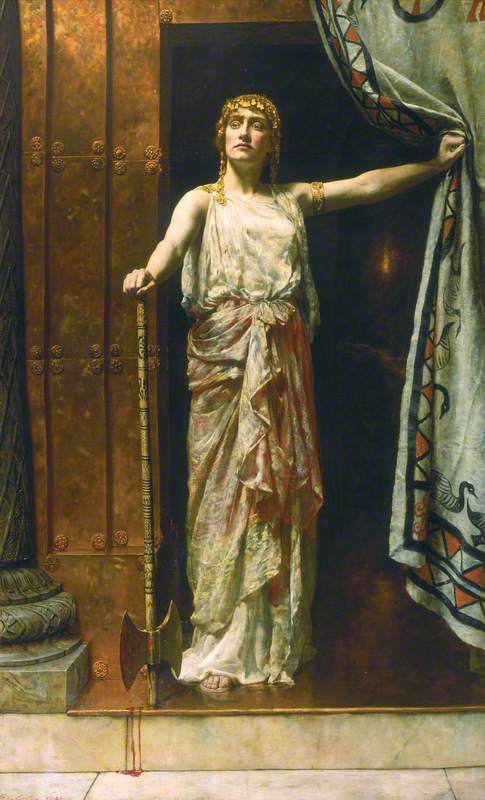

Frequently what endures is a sense of drama and love of narrative – perhaps best seen in Daniel Maclise's Banquet Scene in Macbeth (1840), and John Collier's Clytemnestra (1882). The theatrical paintings here engage with plays as live experiences not merely words on a page. Although often displayed with relevant passages of text, the primary function of paintings based on plays relates to the function of theatre itself – to be seen, not read.

One artist in particular, John Gilbert (1817–1897), was prolific in producing multiple images from literature and performance, in large academy paintings through to the popular press (Illustrated London News, The Graphic). Though frequently overlooked now, Gilbert was one of the foremost proponents of visualising text, and was multi-skilled across the disciplines of watercolour, oil painting, sketching and woodcut engraving.

First Adventure of Gil Blas

1892, watercolour by John Gilbert (1817–1897)

His inspirations range from Miguel de Cervantes to Walter Scott, but he returned repeatedly to the Shakespearean subjects so beloved by Victorian audiences.

Gilbert's reluctance to move with the times and adopt modern techniques (particularly in the choice of paint and colour) and subject matter, however, rendered his work antiquated. There was little space in the late nineteenth-century British art world for a self-confessed Old Master.

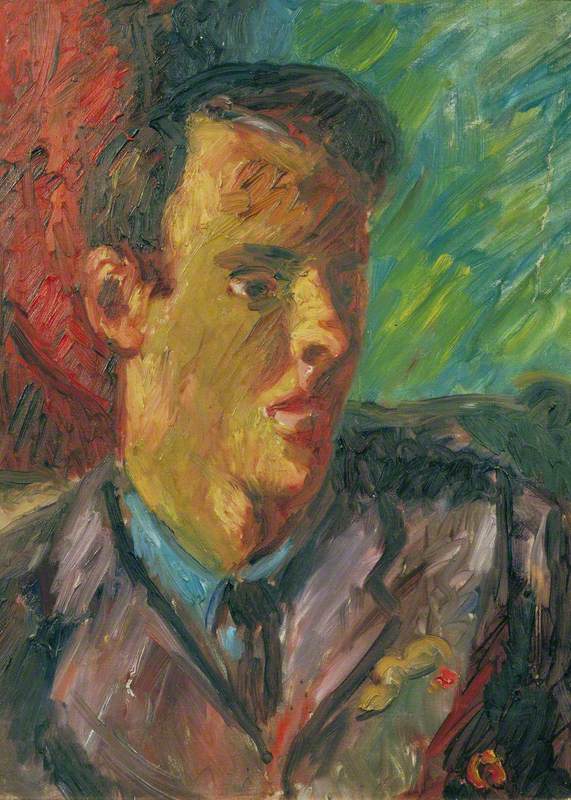

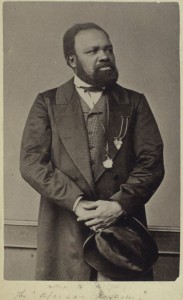

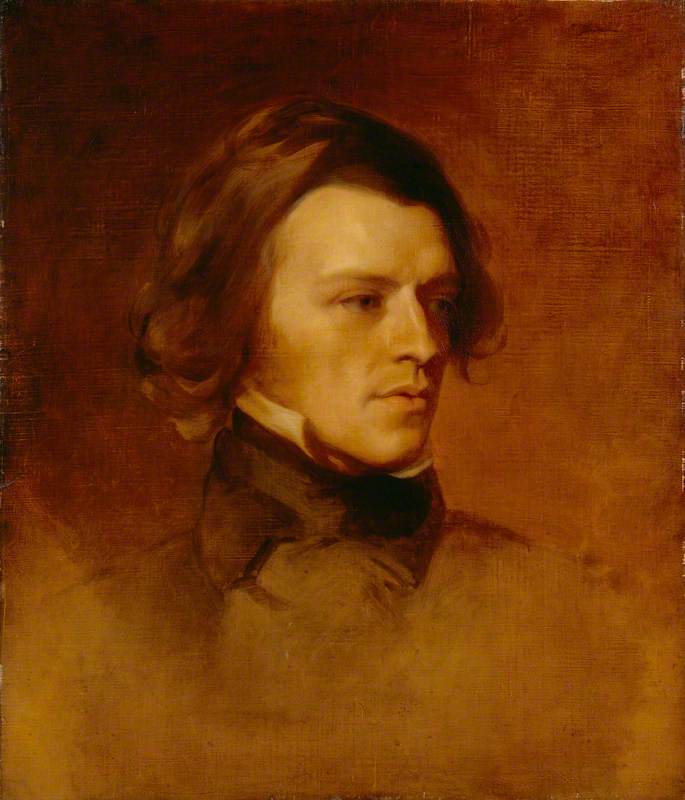

The exhibition also includes portraits (in paint, marble, and bronze) of an eclectic mix of cultural celebrities of their day – actor-managers John Philip Kemble and Henry Irving, opera singer Giulia Grisi, authors Roald Dahl and Henry Yorke, poets Keats, Tennyson, Chaucer and Milton, and musicians and composers Joseph Joachim, Frédéric Chopin and Béla Bartók. The range reveals those with lasting impact, as well as lesser-known figures who were once 'somebody' but have been forgotten (often, it must be said, women, such as Mary Ann Paton and Eliza Chester).

Sir Henry Irving (1838–1905) as Hamlet

c.1885

Edward Onslow Ford (1852–1901)

In examining these types of work, we are invited to ask what the inspirations from our own age to future artists will be. Which poems, books, plays, songs (and indeed, which cultural figures) will still be famous, or even comprehensible to audiences in centuries to come, and which references we collectively understand today will be lost to time?

John Philip Kemble (1757–1823), as Coriolanus

1798

Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

As with all culture, the influences and inspirations we take for granted in the present may become obsolete unless future artists see fit to revive them. Or unless they endure through consistent replication and inheritance, solid in reputation, and – if such a thing is possible – carried forward by their own inherent quality and relevance.

Katty Pearce, Curator at Guildhall Art Gallery

'Inspired! Art inspired by literature, theatre, and music' is at London's Guildhall Art Gallery until 11th September 2022