Writing about anything is one of our most powerful tools. Writing about art is even more extraordinary, as you are writing about something that is not intended to be expressed in words. When you are writing about art you may reveal as much about yourself as about the work of art, which can make it frightening, but also very exciting.

Now by writing about art and entering the Write on Art competition you can win £500, the opportunity to be widely published, and to have your writing read and commented on by a distinguished panel of judges, which this year includes Sir Simon Schama.

You are asked to write a short text, between 400 and 600 words, inspired by a work to be found on Art UK's website, which might include a bit of research, but is primarily based on your personal response.

Write on Art is a competition for school-aged students. It has been going for three years now but it could have been designed for the pandemic and lockdown.

At a time when school and education are disrupted (and it's uncertain for how long) and your UCAS form might be looking a bit sketchy, entering the competition is clearly worth some trouble even if it only goes on your CV. And you might win! People do.

Last year, one of my students at James Allen's Girls' School, where I teach art history, won first prize – Viola Turrell with a piece on Peter Doig – while two Art History Link-Up students, from the charity I run which offers free a Art History A level to state-supported students, were shortlisted.

Viola wrote about Peter Doig's Blotter, a portrait of his brother, from 1993. The Art UK website hosts more than 240,000 paintings by over 40,000 artists and is now adding sculpture, so there is a lot to choose from. I asked Viola how she chose her painting, and she replied, 'Take your time... while the endless choice may seem daunting at first, this is a great chance for you to discover new styles, artists and galleries from the comfort of your home! (And hopefully in person once lockdown measures loosen).'

What tips does Viola have on writing a prize-winning essay about art?

'Remember the judges aren't looking for you to recite facts you found from a quick Google search. Rather, it's the sense of curiosity, a touch of creativity and passion you communicate in your writing that will make you stand out. For instance, note your initial, visceral reaction – did it provoke feelings of awe, disgust, or confusion? How about after you've done some research? Do your opinions remain unchanged, or do you read the artwork a little differently? My advice would be to remain open-minded, inquisitive and honest. Enjoy it!'

A Face Covered with Spider Web*

1920–1960

Madge Gill (1882–1961)

This is clearly excellent advice, straight from the horse's mouth. Viola said how beneficial winning Write on Art has been to her in the intervening year: 'It boosted my confidence and inspired me to write more since. I genuinely have grown to enjoy and find fulfilment from recording and expressing my thoughts on artworks and exhibitions. I've tried to make the most of this by writing for the school magazine, applying for other essay competitions and starting my own blog.'

Viola now plans to become a journalist or art writer as a result of winning the prize, and hopes perhaps one day to edit an art magazine. So I asked the current Editor of Apollo magazine, Dr Thomas Marks, for his tips on writing.

We were thrilled when Dr Thomas Marks, Editor @Apollo_magazine, visited our online Art History classes early in lockdown for inspiring workshops on ‘How to Write on Art’ + to inspire students to enter @artukdotorg’s Write on Art prize. Hear @Tomwmarks here: #arthistory4everyone pic.twitter.com/7brSn4XIMG

— Art History Link-Up (@ArtHistLinkUp) June 4, 2020

One was a very good one indeed, that applies to any situation where writing is involved, whether an email, essay or scholarly article. Tom argues: 'Respect your reader. Assume they have some knowledge, but for different types or article and writing this will be different. Give the reader the information you think they might need – specialist terms that might need explaining, for example. Try to grab the reader's attention early on – you could say something surprising, or use a quotation, or ask an unfamiliar question.'

And Tom's top tip on how to write on art, in particular, may at first seem contradictory to young students with little experience of looking at and writing about art: 'Be confident – and LOOK! Have faith in your ability to look and form opinions. Start with the experience of your eyes. If you have confidence in your eyes, you're bound to find something to say about the work you are exploring.'

However I know that the biggest advantage that teenagers have in writing about art, and in entering this competition, is their age and relative lack of visual experience. I straddle the two spheres of writing about art and teaching art history, having worked as an arts journalist in the 1990s and the 2000s, when art and the art world were rapidly changing. I wrote about mainly modern and contemporary art for national newspapers. Then for the last decade, I have been a part-time art history teacher, and for the last five years I have been running the charity I founded, Art History Link-Up (AHLU). AHLU offers accredited art history courses for state-supported students based in museums and galleries and now, for obvious reasons, it also operates online.

Looking at Titian's 'Bacchus and Ariadne'

As a result of my work with AHLU, I have stood in front of some of the nation's finest works of art with students from diverse backgrounds and wide ability ranges and I have rarely heard the same comment twice. Even more strikingly, almost every time, at least one student will make a comment that illuminates an aspect which that I had never seen before, or at least not in that way.

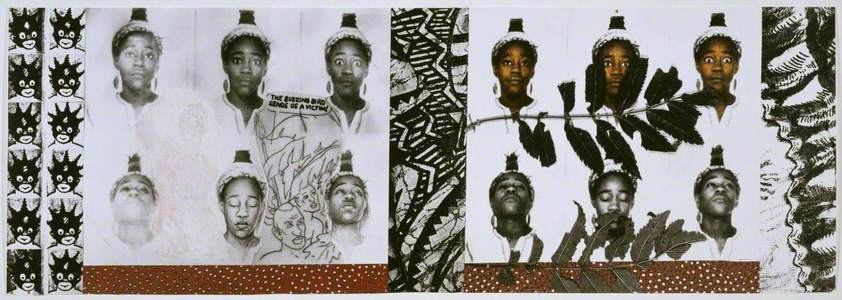

'Oh Muse be near me now and make a strange song'

2011

Zoe Murdoch (b.1976)

Teenage eyes are clear and astute, not cluttered up by received opinions and acquired 'canons of art history', fearless and original. So hone your writing-about-art skills now, in lockdown, so that when the museums and galleries open again you may be able to see things in our great communal treasures that you have never seen before.

For myself, I go back to Viola's prize-winning entry on Peter Doig and think it's significant that she ended with the word 'trance'. I think trance, flow, absorption, call it what you will, is essential for any creative exercise.

So my tip for you is that if you feel absorbed and entranced by the work of art as you are writing about it, it is likely that your reader will be too. For an instant, your reader can see the world through your eyes, which in these times may be one of the most powerful tools and skills to develop. For both writer and reader to pause from the present, and gain a sense of connection to the past and future, may be one of the greatest gifts that art, and writing about art, can offer.

Rose Aidin, Chief Executive of Art History Link-Up, a registered charity offering accredited Art History courses to state-supported students

The deadline for Write on Art 2020 is 31st July 2020