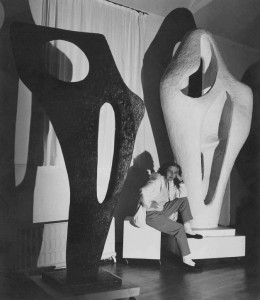

Henry Moore (1898–1986) was acclaimed as one of the leading sculptors of the twentieth century. Known for carving powerful female forms from stone, as well as abstract forms in bronze, his works still grace plazas and galleries in major cities throughout the world. But Moore was also a renowned draughtsman, producing almost 10,000 works in two dimensions – mainly drawings and prints, but also occasional illustrations and textile designs.

The artist's drawings of coalminers are currently the subject of a new book, Drawing in the Dark: Henry Moore's Coalmining Commission, published by Lund Humphries. A comprehensive exhibition of the drawings is showing at St Albans Museum + Gallery from December 16th 2022 until 16th April 2023.

The team are busy putting the finishing touches on our new exhibition, Henry Moore: Drawing the Dark. This free exhibition opens on Friday at St Albans Museum + Gallery

— St Albans Museums (@stalbansmuseums) December 13, 2022

Plan your visit now: https://t.co/PjxueM9s4d #DrawingInTheDark pic.twitter.com/V27NgDBIL5

As a War Artist, Moore made highly expressive drawings of Londoners sheltering from the Blitz in Underground stations between 1940 and 1941, which helped establish both his critical reputation and his popularity. Most depict Londoners during the blackout, sheltering from the bombing on the platforms and in the tunnels of Underground stations.

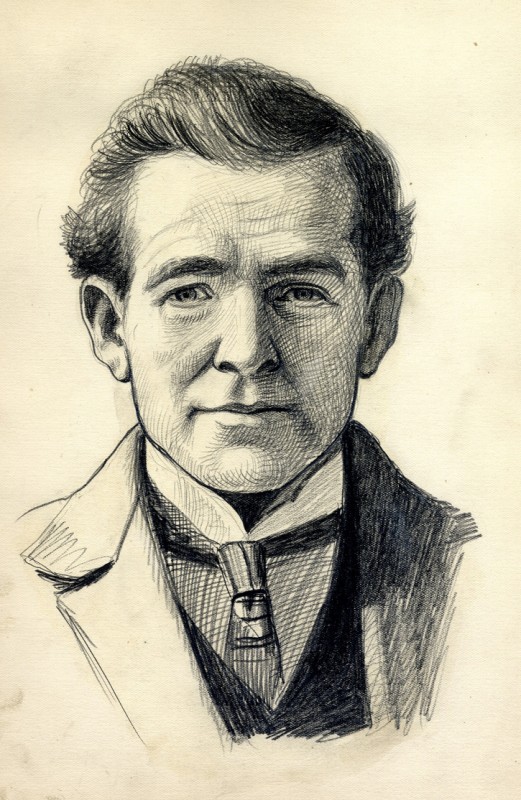

Henry Moore (1898-1986)

— Henry Moore Studios & Gardens (@henrymooresg) February 26, 2022

'Mother and Child among Underground Sleepers' 1941 pic.twitter.com/epf7ygNV2m

These drawings tell us much about the times the artist was living through, the plight of the people he portrayed, and how he viewed the human figure as sculptural form. Kenneth Clark once described them as 'among the most precious works of art of the present century'.

Moore's second project as a War Artist depicted coalminers working at Wheldale Colliery in his home town, Castleford in Yorkshire. They are less well known, but arguably more informative about his life, working processes, and deepest feelings.

Pit Boys at Pit Head

1942, pencil, wax crayon, pen & ink & wash on paper by Henry Moore (1898–1986)

These drawings appear neither to advance the modernist style of his earlier sculpture, nor to connect with his favoured themes, the reclining female form and the mother and child. This perhaps explains why they have sometimes been disregarded or viewed as a distraction for Moore. But because the project challenged the artist in new ways, and because returning to the pit where his father had worked for many years gave the subject matter such personal significance, they are deserving of closer study.

A Miner at Work

1942, wax crayon, pen & ink & wash on paper & card by Henry Moore (1898–1986)

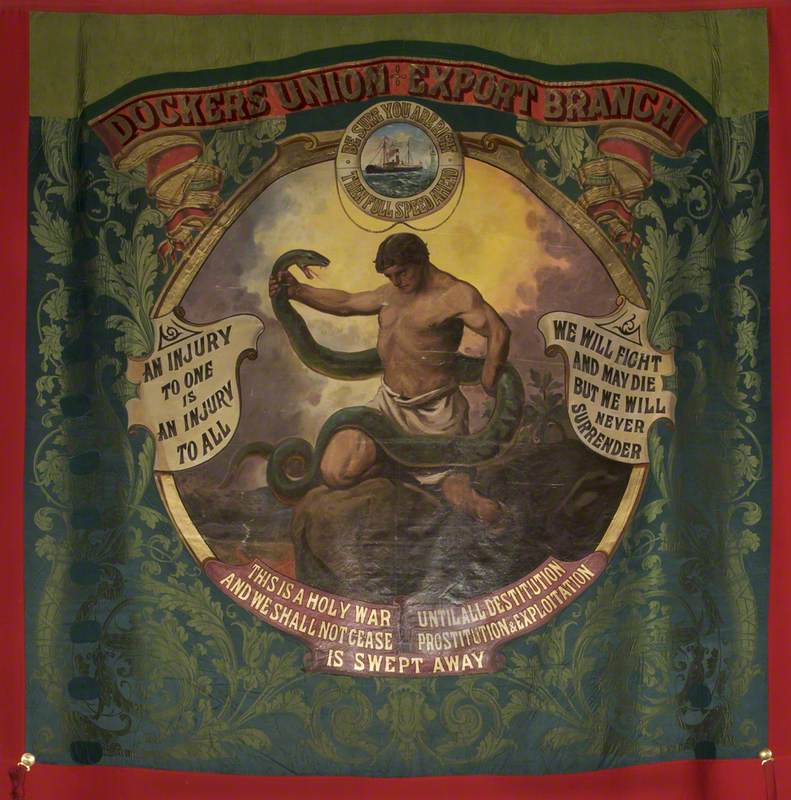

Commissions for the War Artists' Advisory Council (WAAC) were always political, since the images produced served as wartime propaganda. But Moore's drawings are also political in that they reflect a socialist outlook, depicting the tough working conditions of miners underground. George Orwell, in The Road to Wigan Pier published five years earlier, described mining in ways more expressive of the writer's politics. But both Orwell's essay and Moore's drawings are examples of social realism, harking back to nineteenth-century precedents, such as Émile Zola's novels and Gustave Courbet's paintings.

In the 1930s, over 750,000 people laboured in British coal mining. Yet in 2022, coal has almost disappeared from public view. The recent energy crisis may have raised awareness of where our power and heat come from, but the climate crisis has branded coal as the most undesirable fossil fuel. Britain's economy and people's livelihoods now rely more on the digital world of service industries than on manufacturing or mineral extraction. Forty years after so many mines closed in the 1980s, little evidence remains of Britain's collieries, besides an occasional memorial winding wheel.

Colliers Corner (Howe Bridge Pit Memorial 1879–1959)

1999

unknown artist

Ex-miners who can recall working underground are also fast diminishing in number. Moore's drawings depict an industry which existed in a very different world from contemporary Britain.

At the Coal Face

1942, pencil, wax crayon, pen & ink & wash on paper by Henry Moore (1898–1986)

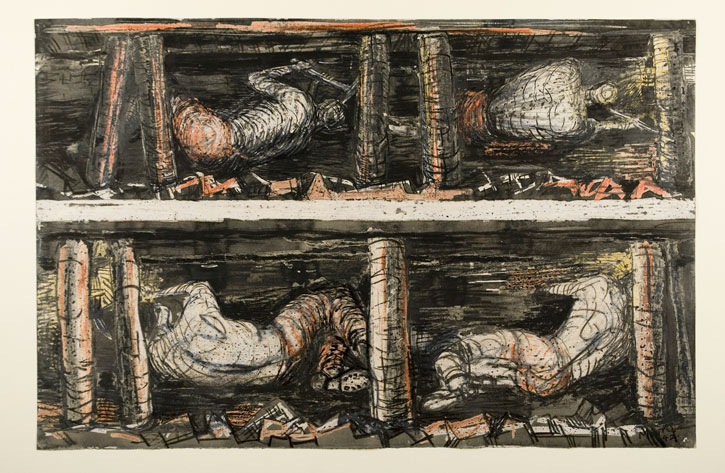

The commission challenged Moore to depict both the actual darkness of the pit, and the metaphorical darkness of these workers' lives. Compared to the passive, worn-down shelterers in London's tube stations, Moore's coalminers are dignified men, fully focused on their strenuous work.

The shelterers were temporary visitors, waiting only for the 'all-clear' before re-emerging into the light. Moore's miners were condemned to spend most of their waking hours underground, performing physically demanding work in extremes of danger, dust and darkness. There is little colour in the drawn tunnels, scarcely any expression of emotion on the workers' faces. These are stoical men, engaged in hard labour, which appears grimly inevitable and unseen.

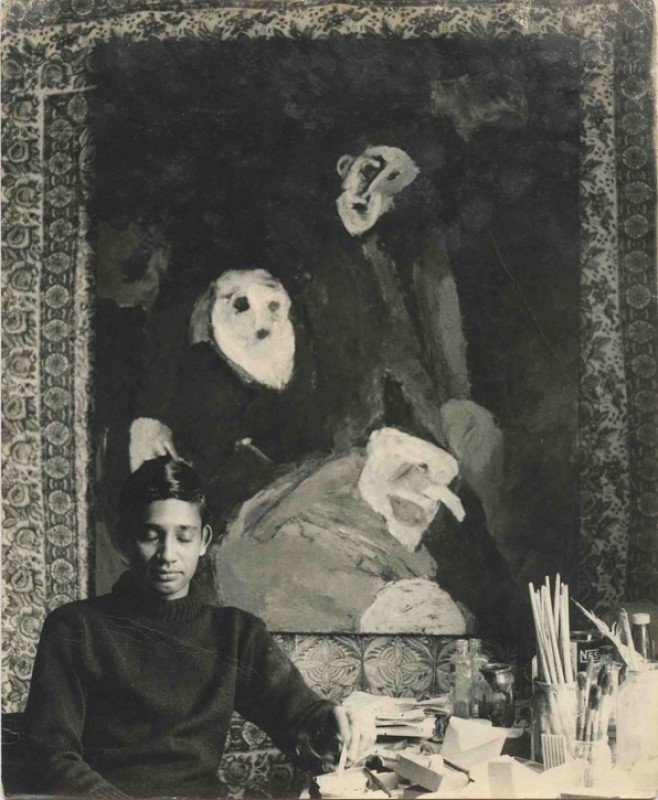

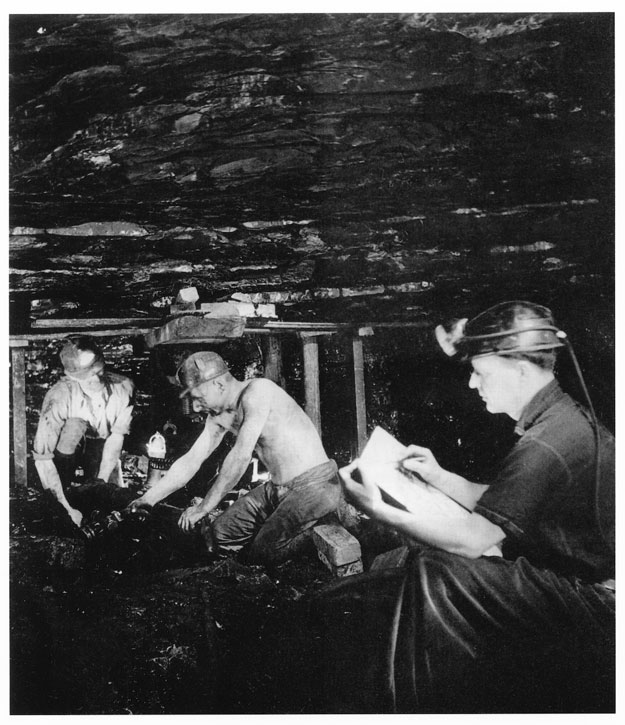

Henry Moore sketching two miners, Wheldale Colliery, Castleford

1942, photograph by R. Saidman

Moore visited Wheldale twice for the coal mining project, in December 1941 and January 1942. He later recalled finding the conditions on his first day physically challenging:

'If one were asked to describe what Hell might be like, this would do. A dense darkness you could touch, the whirring din of the coal-cutting machine, throwing into the air black dust... all this in stifling heat. I have never had a tougher day in my life of physical effort and exertion.'

As a soldier in another Hell, the trenches of the First World War, Moore had been seriously injured by gas. Underground, the sounds, the confinement and the constant threat of gas must have stirred discomforting memories as he worked.

Moore filled his Pit Notebook (Coalmining Notebook A) with over 90 sketches from observation, mainly in pencil. On one day he was accompanied in the mine by a press photographer, Reuben Saidman, whose images show Moore making several of the studies in the notebook. They were published as a photo-essay in Illustrated magazine on 23rd January 1942.

Returning to his home at Perry Green in Hertfordshire, Moore spent several months making studies in three further sketchbooks, in preparation for the finished drawings. Many are annotated with the page numbers of studies in the Pit Notebook on which they are based. These development drawings demonstrate how carefully the sculptor studied miners' working poses, developed compositions, and exploited a complex mix of drawing materials, in order to convincingly conjure 'form out of darkness'.

From them, he completed 28 finished drawings, eleven of which were bought by the WAAC and later distributed to civic galleries in major industrial cities around Britain. They show Moore's powers of observation, his understanding of the mining process, and how he used his knowledge of art history, especially Masaccio and Honoré Daumier, to convey the strength and dignity of these miners. They mostly lack personal characteristics, but instead represent universal examples of human labour.

This commission drew Moore's attention to the masculine aspects of his life – men at work, his relationship with his father, the male body as subject matter, military service, and labour politics. Moore admitted that the experience was sometimes difficult, but he also acknowledged that it had opened new creative avenues for him. Through it, Moore said, he 'discovered the male figure and the qualities of the figure in action.'

Four studies of miners at the coalface

1942, drawing by Henry Moore (1898–1986)

Although Moore's preoccupation with the female form continued, he did later explore men in action in his series of Warrior sculptures. Moore's Helmet Head sculptures from the 1950s also suggest that the idea of wearing a protective helmet, seeking out subjects by its torchlight, continued to interest him.

Thirty years after they were made, these drawings still lingered in the elderly sculptor's memory. In 1973–1974, Moore illustrated a selection of W. H. Auden's poems in a series of dark monochrome lithographs. When exhibited at the British Museum, Moore placed them alongside some of his mining drawings. These prints 'may be connected with the coalmine drawings', he explained, 'where there was the problem of getting form out of darkness – of making the light from the miners' helmet-lamps produce figures out of thick blackness – of drawing in the dark.'

Chris Owen, art historian, author of Drawing in the Dark: Henry Moore's Coalmining Commission, published by Lund Humphries

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.