Content warning: this story contains reference to sexual assault.

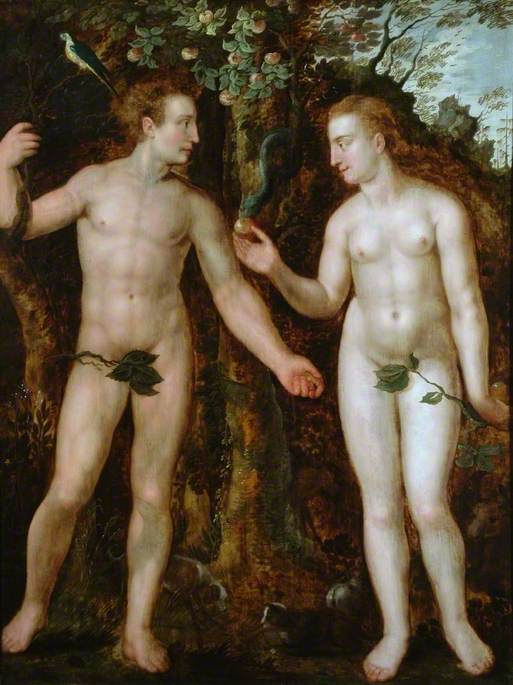

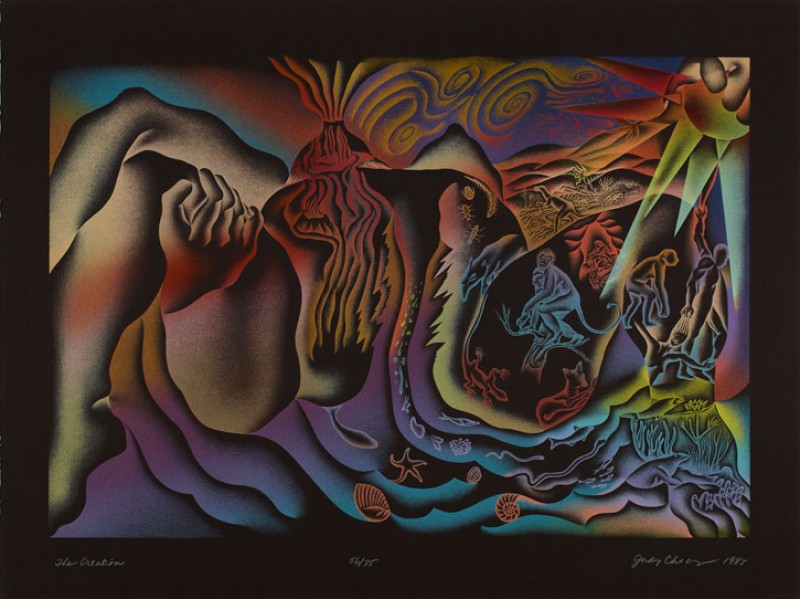

It has long been stated that, as belief systems go, the Greek myths present a pretty anthropomorphic set of characters. Rather than following the Biblical notion that 'man is made in [a] god's image' these ancient deities of the mythological world are closer to humankind: the good, the bad and the utterly atrocious.

Indeed, badly behaving gods and demi-gods were at times depicted as brave, adventurous and sometimes warm-hearted. Yet, at other times they were shown to be callous, cold, and morally corrupt, especially by modern standards. As the team captain in the ultimate posse of immortal beings, Zeus embodies Greek mythology's problematic take on love and desire – or what the Greeks might have called 'eros'.

One might argue that the legends of Greek mythology have underpinned or influenced historic attitudes towards sex, love, and relationships. By definition, eros is about passionate, physical desire, which often emerges as a theme in its myths, epics and legends.

In a report published in January 2019, Brook, the well-being charity aimed at young adults, found that 56% of university students said they'd experienced unwanted sexual behaviour but only 3% of them reported it to the authorities. Findings such as these may seem novel on the radar of the collective conscience, as it's only relatively recently that the question of unwanted sexual behaviour has been raised as a serious question. In truth, this is an issue as old as time itself.

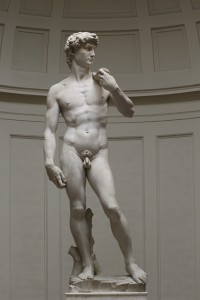

The perpetrator's backstory is not always one we could predict, nor does he have a single image. He may show up as the stereotypical lurcher of small screen horrors, or as a swaggering macho-type. Considering the latter, imagine a god (in place of a man) holding a thunderbolt as opposed to, say, a basketball.

Zeus, the king of Mount Olympus, embodies this problem perhaps more than any other mythological figure.

Winning the battle against the Titans made Zeus the king of the gods, which may to some extend explain his sense of entitlement. According to legend, there isn't a thing Zeus doesn't achieve or 'win', usually by force.

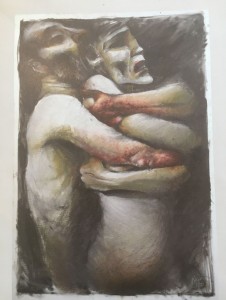

The rape of Europa

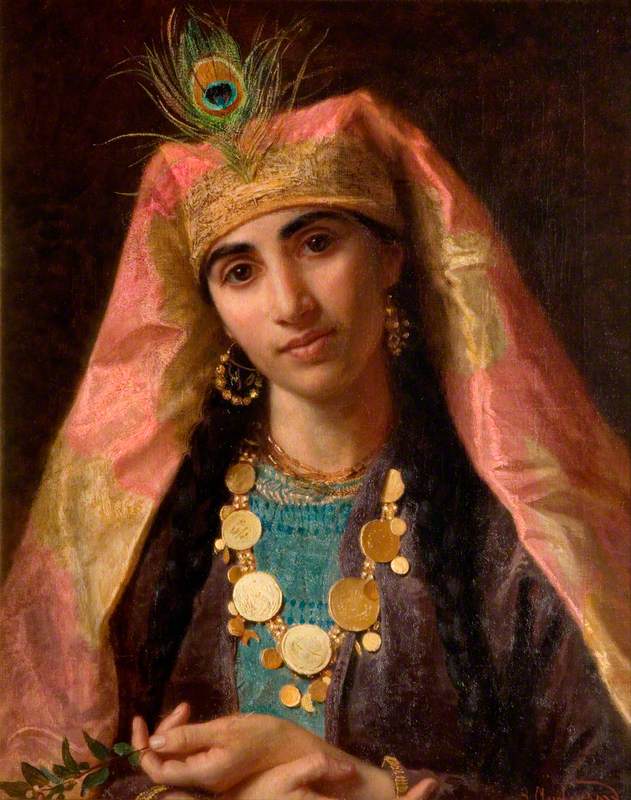

In the story of Europa, the god-king spots the girl Europa picking flowers, and decides he must have her.

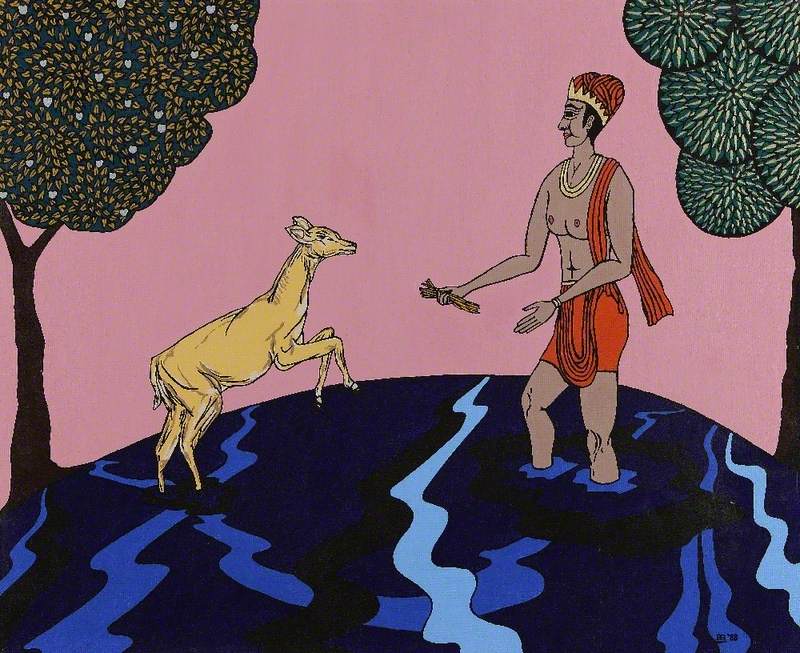

Zeus turns himself into a docile white bull, and when the girl climbs upon his back, he swims away to Crete. It is on the island that Europa is 'seduced' (raped) by the god, and bears his children.

Leda and the swan

In the tale of Leda and the swan, Zeus's pursuit of the Queen of Sparta leads the cunning Leda to metamorphosise several times in order to escape his chase. In one version of the story, Zeus matches Leda's shape-shifting abilities by morphing into animals that surpass her versions in strength: a swan to her goose, for example.

In another, Zeus lowers Leda's guard by pretending he is being chased by an eagle and then attacks.

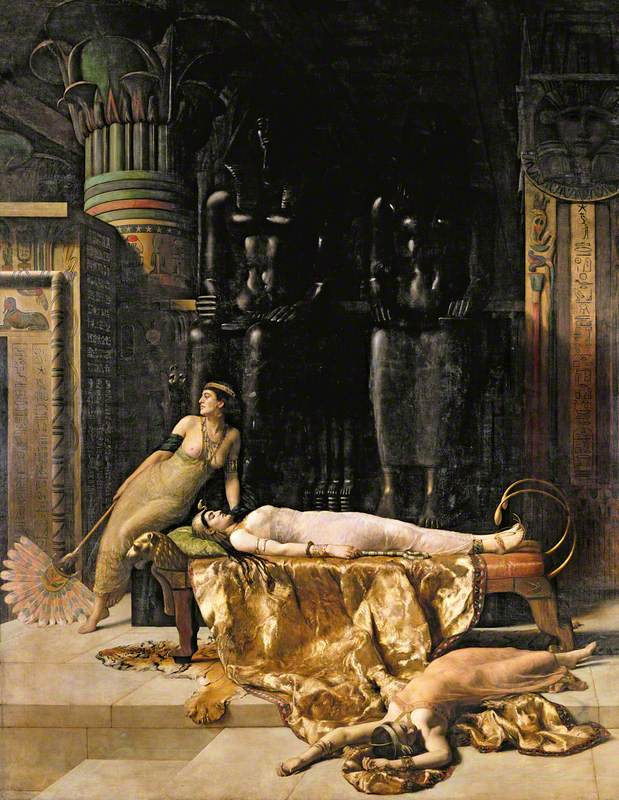

Danaë and the golden shower

In another case, that of Danaë and the golden shower, a woman is caught between two male figures who take charge of her future well-being, against her will.

Her father, King Acrisius, locks her in a chamber after learning of a prophesy foretelling his murder at the hand of Danaë's future son. Zeus takes advantage of her predicament by infiltrating her prison and impregnating her in the guise of a golden shower.

Disturbingly, artists have typically depicted the moment as zen-like, consensual, even.

But did Zeus offer to break Danaë out of jail, either way? Er, no, he did not. Legend has it that she had to continue to protect herself from predatory men, only aided by her hero-son.

King Acrisius cast Danaë and her son into the sea in a wooden chest. Surviving that, King Polydectes then only agreed not to forcibly marry Danaë if Perseus brought him the head of the Gorgon Medusa.

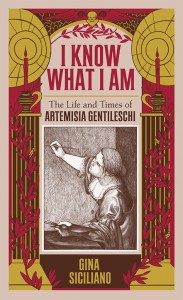

Yet, where rape culture is clearly a shocking concept to wrap one's head around, it's the subversion of long-held beliefs about romance (or what the Greeks called 'eros' – sexual love) that can alter our understanding of the world around us. Art history tells us we should go back to the legends of ancient Greece, in which rape and predatory sexual behaviour are commonplace, and therefore, normalised.

Such violent acts and intentions aren't always carried out by a single perpetrator; sometimes there are encouragers – today we would call them 'enablers'. A study published in 2014 in the journal Violence and Gender reported that 32% of American college-aged men admitted they would rape if they could get away with it.

Persephone and Hades

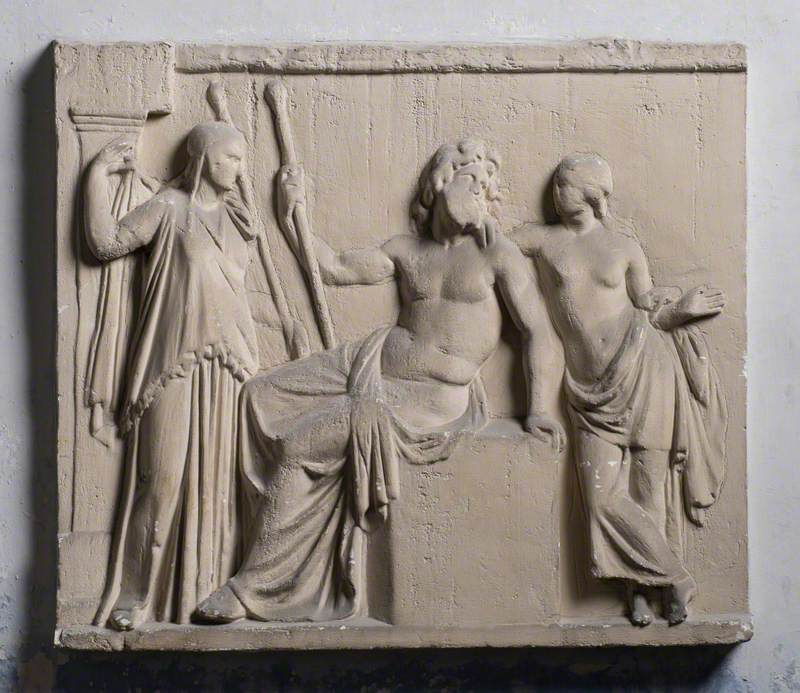

Case in point, Zeus helped his brother, Hades, abduct Persephone (the Roman Proserpina) to the underworld, and the road home remained complex for the young goddess of spring.

The Rape of Proserpine

(copy after Peter Paul Rubens) mid-17th C

Willem van Herp I (c.1614–1677)

Demeter's joy at her daughter's return is plainly seen in Leighton's piece.

Although Zeus hadn't done the deed, he'd given his blessing without so much as an alert to mother or daughter of his plan – clearly, that would be too much.

Paris and the golden apple

Another account is that of Troy, where war erupted because two opposing monarchs were fighting over the love – or, rather, possession – of a beautiful woman.

But it began with three competitive goddesses, Hera, Athena and Aphrodite, who each promised the Trojan prince Paris a reward for naming one of them the most beautiful. Each of these goddesses had been affected by Zeus's antics, one way or another, and one might imagine him finding the entire debacle amusing.

Through tales of Zeus, we've seen how questionable mythological tales of romance can be.

Be that is it may, why should they matter to us now? These legends set a powerful precedent, one which enables and perpetuates harmful behaviour towards women. Of course, in such cases, there are countless other factors to consider, but when violent acts are celebrated in storytelling, it makes it harder to fight them in real life.

This is especially true if these actions stem from people who are supposed to be our leaders, such as gods, heroes and others in positions of power...

Patricia Yaker Ekall, journalist