Art teachers often tell their students 'if you want to draw or paint something realistically, you have to look at it in real life'. This rule poses a problem for artists looking at wild

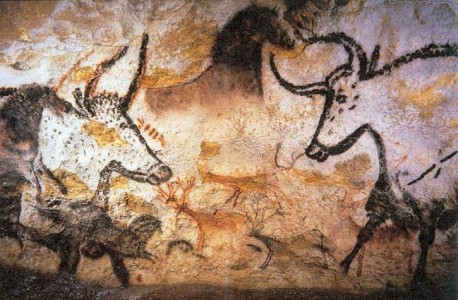

Today we have photographs and nature documentaries to help us understand animals, but before these things were readily accessible, artists had to conjure the elusive creatures from other artists' pictures, their imaginations, or from studies in person. Unfortunately for animals, during the

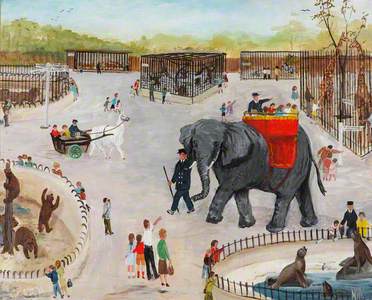

The history of zoos reflects how we look at animals: animals have been captured in enclosures and on canvas, for entertainment, education, or a little bit of both. Zoos today have the tricky task of adapting with changing cultural attitudes to animals and the environment, and advances in animal welfare. Partly tourist destination, partly Noah's Ark, understanding zoos can be difficult: we have a number of paintings on Art UK which help illustrate this complicated history.

London Zoo's variety of architectural styles

2014

Animals as captives

Early animal artists, such as Frans Snyders, used the beautiful feathers and furs of wild creatures to give texture and depth to his still lifes or hunting scenes. His paintings show a mix of dead and alive animals, mostly ones to be found (and eaten) in Europe. You can imagine the artist working in front of a table piled with pelts, dead birds and vegetables.

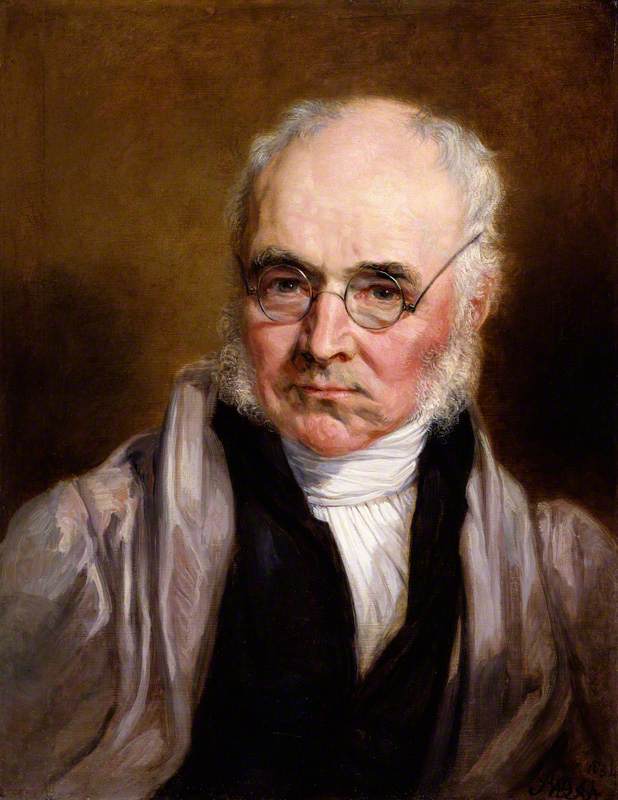

Some talented sixteenth- and seventeenth-century artists, such as Rembrandt, Durer and Rubens, included more exotic species in their paintings, like hippos and lions. Their successes were thanks to encounters with captive animals on display, earlier prints, published anatomical studies, and compositional skill (as explained in this fantastic Slate article).

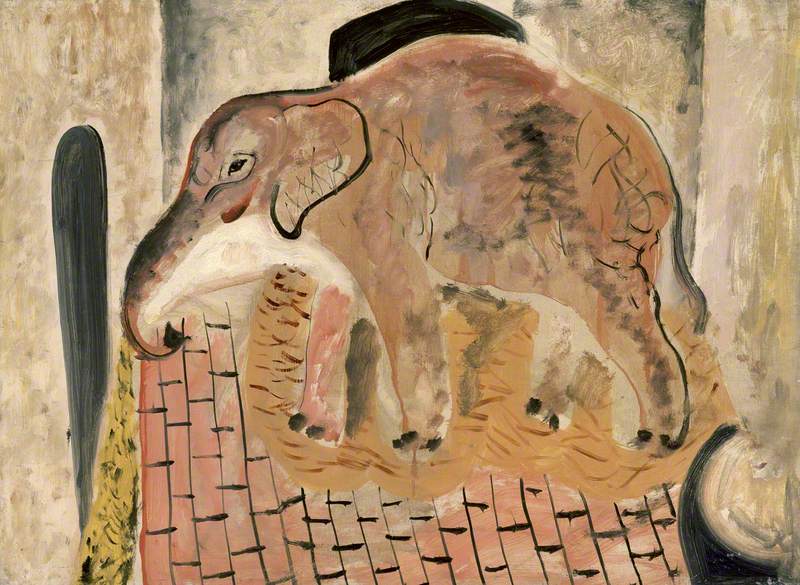

But wild animals were also drawn and painted for reasons other than to decorate stately homes; their images were captured so that people could learn about the natural world. Consider how hard it would be for a traveller from the Middle Ages to explain an elephant to people who hadn't seen one before – which may excuse the appearance of the chubby grey creature on the left in this painting.

Orpheus Charming the Animals

c.1672

Thomas Ffrancis (active 1635–1679) (attributed to)

The urge to see and know about exotic animals was gradually satisfied by pictures: anatomist Dr William Hunter commissioned works from George Stubbs because he knew the artist to be talented in anatomical study – as demonstrated by his splendid Whistlejacket (though Stubbs' depiction of an Indian 'stag' is a composite of British and Indian species (i)). The Moose was commissioned because Dr Hunter was keen to prove his theory that the moose was different to the Irish elk (ii).

Dr Hunter must have been familiar with the errors that could be introduced by artists working from poorly preserved specimens. One beloved example of this problem is the Horniman Museum's overstuffed walrus. Modern visitors may think he looks like a tusked balloon sitting on an iceberg, but if you hadn't ever seen a live walrus, how would you know the skin is supposed to have

Transporting live animals grew in popularity until the menagerie became common during the nineteenth century. Early forerunners of zoos as we know them, these motley collections of exotic animals were kept in conditions we'd see as barbaric today. Originally collected by royals and other people of influence, later menageries ran as businesses, such as that in the Exeter Exchange on London's Strand. Lord Byron documented a visit there in his diary:

'…The elephant took and gave me my money again – took off my hat – opened a door – trunked a whip – and behaved so well, that I wish he was my butler.' – Life, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron (1839)

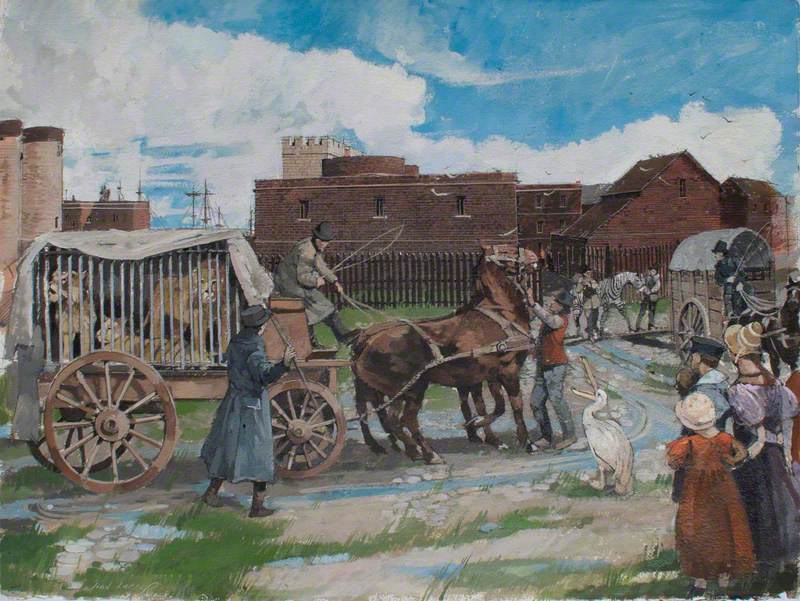

The Exeter 'Change declined in popularity after its elephant Chunee killed a keeper and was shot; the creature's agonised cries were heard across the Strand. The Exeter 'Change and the Royal Menagerie at the Tower of London were closed, and their remaining animals sent to a new site in Regent's Park, which opened in 1828 – as imagined in the below scene. The opening of London Zoo, the first of its kind, marked a new era for urban society's relationship with captive animals.

Last Days of the Royal Menagerie and Moat, c.1841

2002–2003

Ivan Lapper (b.1939)

Animals on display

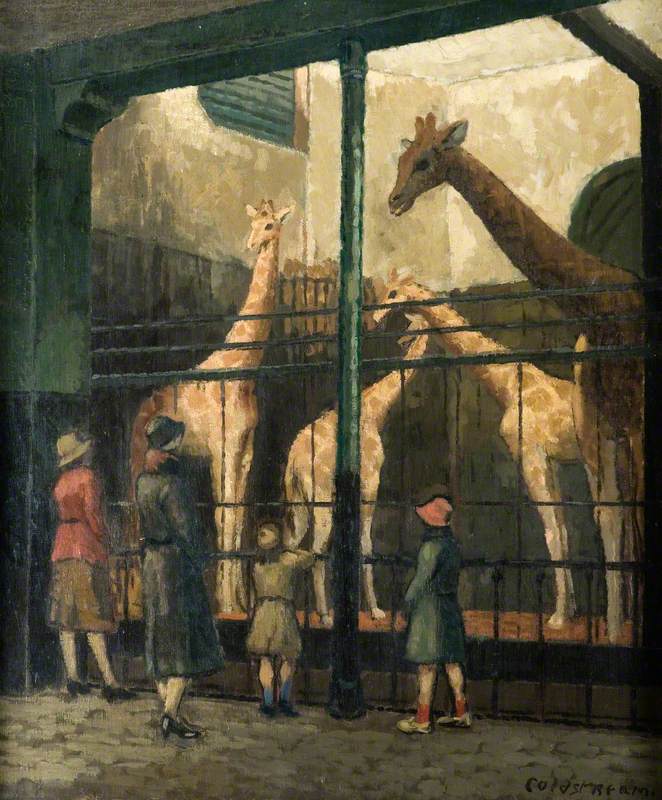

Within a decade of The National Gallery opening in Trafalgar Square, London Zoo opened to the public in 1847, having previously allowed access mainly to Zoological Society Fellows. This was the era of scientific discovery and moral instruction: Dr Hilda Kean explains that galleries and zoos at that time were 'places where you go along and look at things… a way of being educated and improving yourself… becoming civilised by looking.'

Scarborough, Interior of the Aquarium

19th C

British (English) School

It is difficult to imagine how transformative these new experiences were: in 1853 London Zoo opened the first public aquarium, allowing the public to see live fish swimming, from a side-angle, for the first time (the first recorded photograph of a living fish was taken in 1854 (iii)). Comparing paintings from before and after the nineteenth century, you can see a change from flat studies of dead catch, to fish swimming underwater.

The reimagining of animals within nature was popularised by the zoo enclosure designs of Carl Hagenbeck, a wealthy merchant who traded in animals (and sometimes humans). His zoos used an architectural feature similar to a 'ha-ha' in landscape design: replacing a visible barrier with a hidden trench means the gaze of a viewer is not interrupted – a zoo visitor can

Yet, like in art, development in enclosure styles was not a straightforward path, but various approaches were influenced by other cultural ideas. Berthold Lubetkin and the Tecton group created several modernist enclosures for Dudley and London Zoos, now listed structures. The interior of the Tecton

Tropical Bird House at Dudley Zoo

2014

Lubetkin took the approach that design could emphasise characteristics of animals, for example, highlight the stripes of a zebra or showcase a penguin's waddle. Yet almost all Lubetkin's 'Tectons' are no longer used, or are housing different (often much smaller) animals than those they were intended for. The winding slopes of Lubetkin's Penguin Pool now encircle a fountain rather than the beloved birds, as the hard concrete, shallow water and echoing walls weren't suitable for their feet, swimming or calling behaviour. But the high regard for modernist art means the pool will remain in London as a grade-listed building – despite the urban zoo being limited in space.

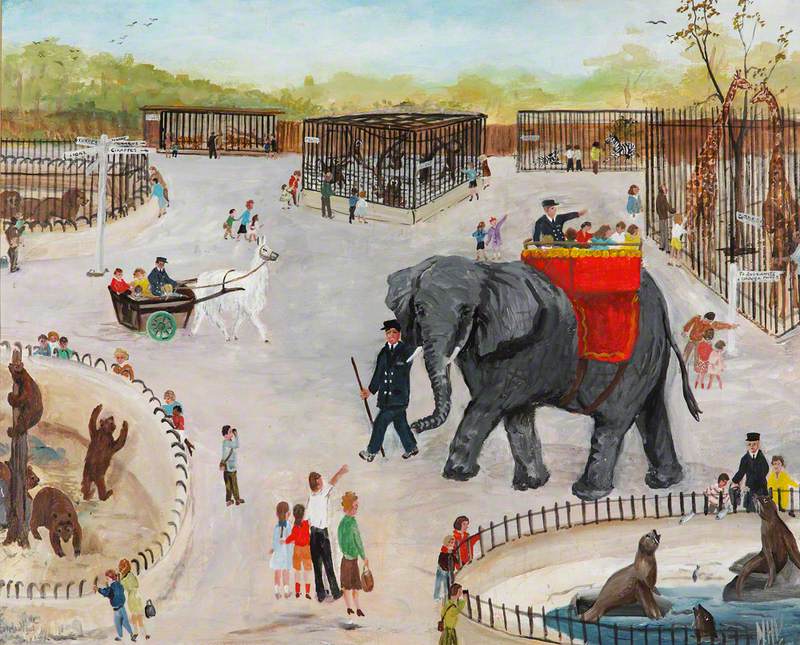

Zoos in the twentieth-century became multi-faceted: they exploit Romantic ideals through landscape design, present nature's characteristics within rational order through modernism, and also entertain. Zoos are embedded in the public consciousness as a grand day out for all the family, often painted by artists as a fixture of daily life within the topography of the city.

Zoo animals as nature's advocates

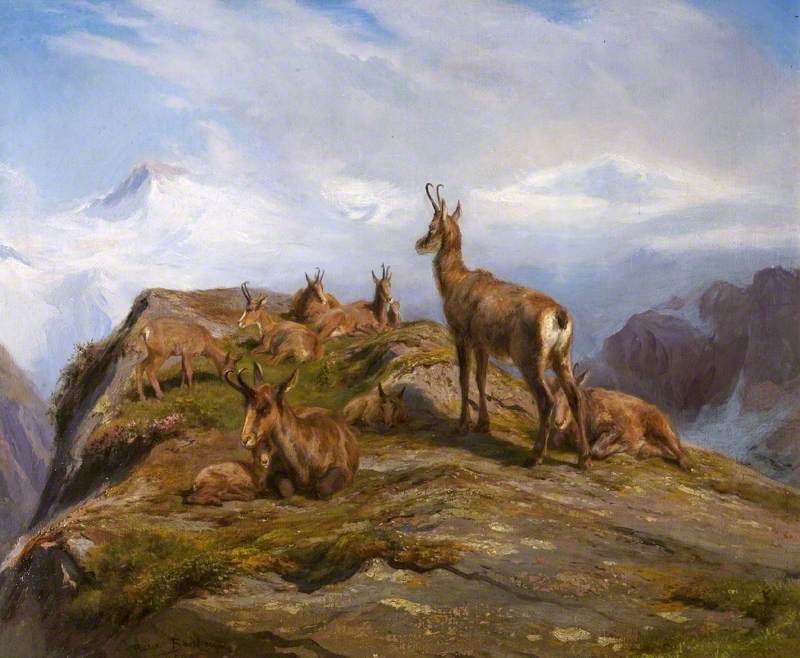

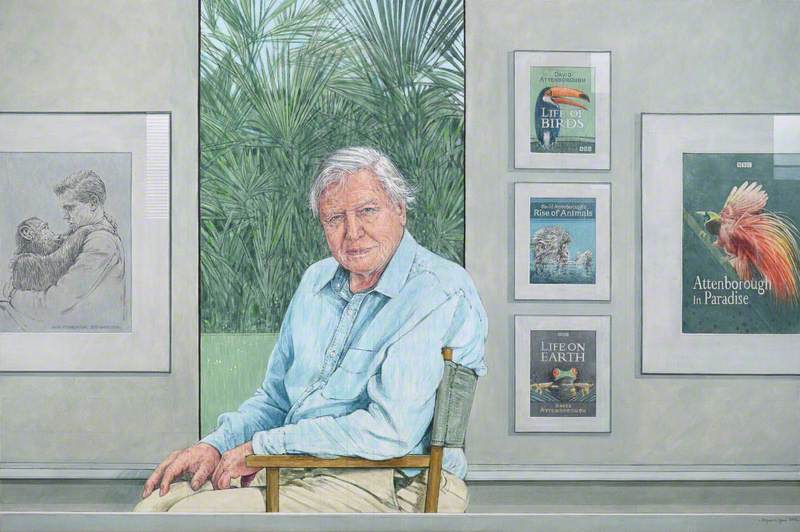

Painters such as Thorburn, Bonheur and Tunnicliffe were early forerunners of animal artists who actually 'got out there' to paint animals in the wild. Now animal painters have more freedom than ever to go outside, ironically despite declining wildlife populations. Hagenbeck's approach of alluding to nature through design continues to be a popular way to build

It's hard not to acknowledge that today's multi-purpose urban zoos can feel awkward, despite their environmental efforts. If zoos design their enclosures to be more 'natural', do they run the risk of 'losing critical consciousness' (iv)? If zoo enclosures are the result of designers and architects, claiming to be natural could be a dangerous and short-sighted approach.

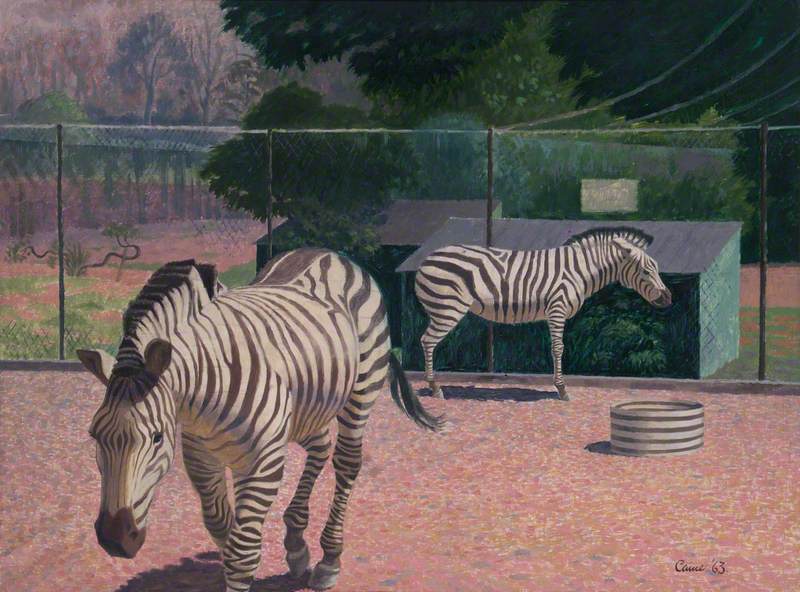

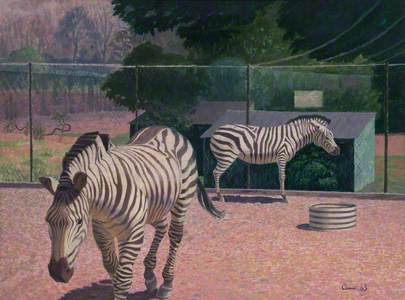

It feels important that our relationship with animals continues to be thought about critically, and artists are well-placed to explore these themes. Artists may use with colour and composition to imply a sense of melancholy, or disjointedness: wild creatures often don't appear to fit in

Jade King, Art UK Head of Editorial

(i) Tate, 'Stubbs: A Celebration: Room 2'

(ii)

(iii) J. Barrington-Johnson, The Zoo: The Story of London Zoo, Robert Hale, 2005, p.37

(iv) Jeffrey Hyson, 'Jungles of Eden: The Design of American Zoos' in Michel Conan, Environmentalism in Landscape Architecture, Doakes, 2002, p.25