The cheetah that Sir George Pigot, outgoing Governor General of Madras, brought to London in 1764 and presented to George III, was the first of its species ever seen in the United Kingdom. It was also lucky to be alive. Most of Pigot’s collection of ‘wild beasts and curiosities’ had perished during the eight month sea passage from India.

Although primarily known – and celebrated – as a painter of horses, George Stubbs was an obvious choice of artist when Pigot commissioned, for £120, a portrait of his exotic gift to the King.

Only the previous year, in 1763, Stubbs had painted Queen Charlotte’s South African zebra standing forlorn in incongruous English woodland.

He would later produce an oil study of another livestock gift to Her Majesty: the nilgai, a large Indian antelope. The anatomist William Hunter commissioned that picture as a visual aid for a lecture he delivered to the Royal Society, during the course of which he remarked:

'Good pictures of animals give much clearer ideas than descriptions. Whoever looks at the picture... by Mr. Stubbs, that excellent painter of animals, can never be at a loss to know the Nilgai, whenever he may happen to meet with it.'

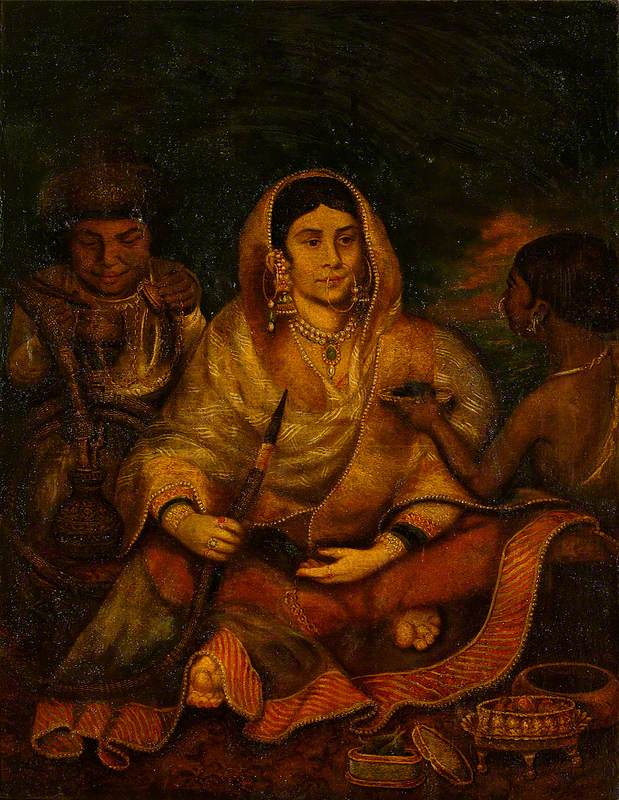

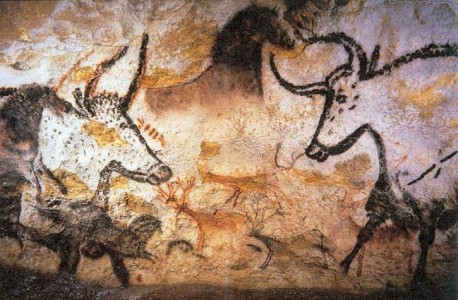

Easily tamed and trained, cheetahs had been used as hunting animals by the Mogul Emperors for hundreds of years. In the sixteenth century, Akbar the Great was said to have kept a thousand of them for that purpose, as the English landed gentry kept packs of foxhounds. When told of this royal precedent, George III’s uncle, William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland – sanguinary victor, eighteen years earlier, of the battle of Culloden and known to history as ‘Butcher Cumberland’ – was eager to put the King’s cheetah through its paces. He arranged a demonstration in Windsor Great Park on 30th June 1764.

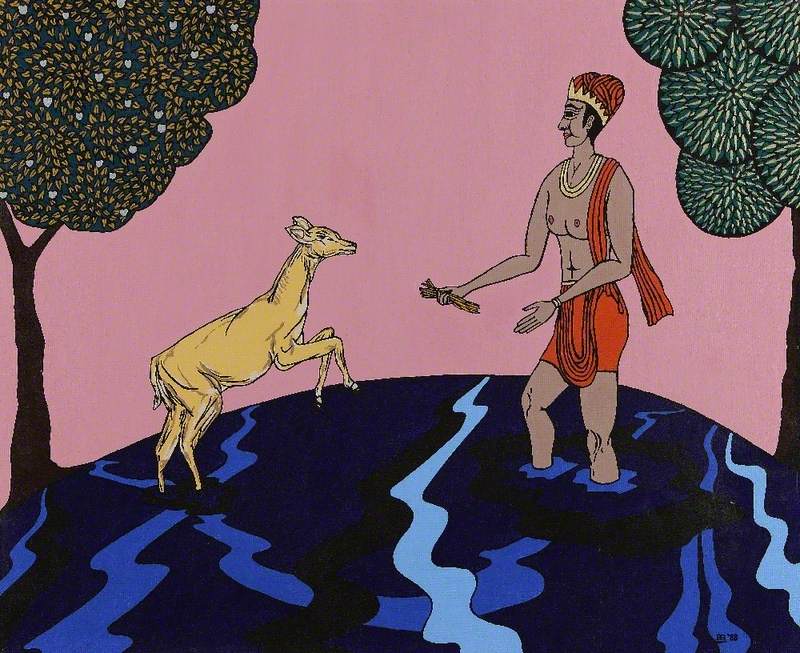

A stag was placed in an enclosure of the royal paddock while the cheetah was prepared for its trial by Pigot’s Indian servants. First the animal was ‘hoodwinked’ by a scarlet blindfold placed over eyes and face and tied under the throat. One of the servants knelt, holding it by a restraining sash around the hindquarters. He then pulled back the hood leaving it, bonnet-like, on the top of the head and allowing the cheetah a first sight of its quarry. The other servant gestured towards the stag and the predator was unleashed.

The St James’s Chronicle reported what happened next, referring to the animal by the name of the only Indian big cat known to eighteenth-century England:

'The Tiger attempted to seize the Stag by the Haunch, but was beat off by his Horns; a second Time he offered at his Throat, and the Stag tossed him off again; a third Time the Tiger offered to seize him, but the Stag threw him a considerable distance, and then followed him, on which the Tiger turned Tail.'

The Duke of Cumberland and his guests were not entirely disappointed of their sport by the cheetah’s ignominious performance. Chased out of the enclosure by the stag, it ran off and found a herd of more cooperative deer, one of which it seized by the throat and killed. By the time the Indian servants caught up with the animal they found it placidly lapping at the blood of its victim. They hoodwinked the animal again then ‘put a Collar round his Neck, with Chains, and, after feeding him with Part of the Deer, led him away.’

The cheetah’s adversary was also rewarded. Lloyd’s Evening Post reported that Cumberland gave instructions ‘for particular care to be taken of the stag that so bravely defended himself against the tiger... and likewise ordered a large silver collar to be put around his neck for distinction and greater safety.’ He would henceforth lead a protected existence harrassed by neither man nor beast.

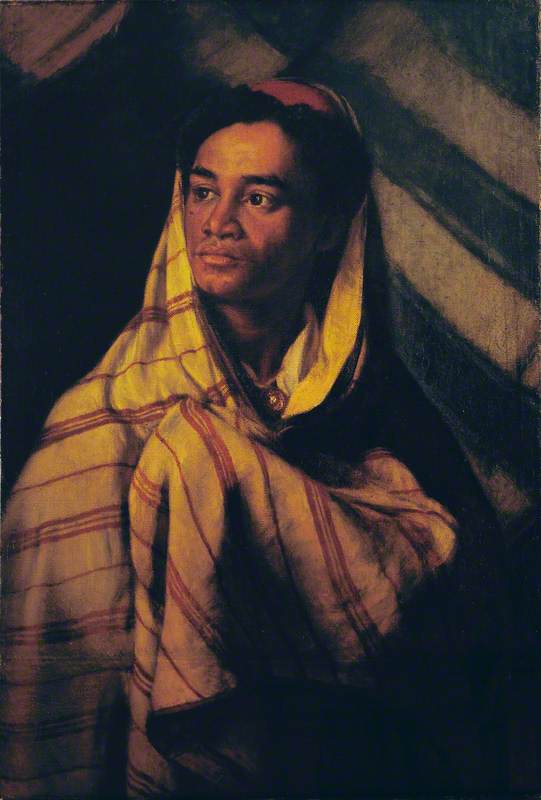

In an age when foreign visitors were pictured at best as colourful exotics, at worst as sinister or ridiculous caricatures, Stubbs endowed the servants with a grace, nobility and authenticity equal to the magnificent creature they care for.

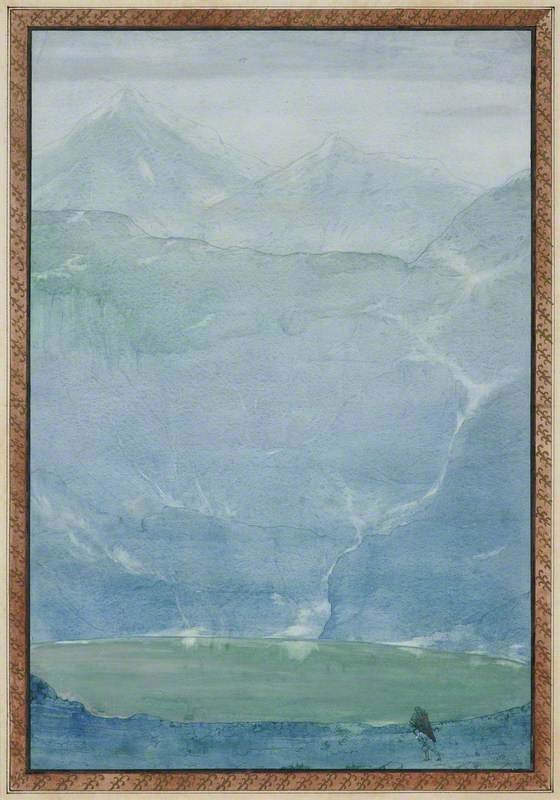

Stubbs’ painting was not intended as a literal record of the demonstration in Windsor Great Park. The landscape in which he placed cheetah and attendants is an artificial composite far removed from their native hunting ground. A vista of the Cheshire Plain – Beeston Castle in the distance – appears below the standing servant’s outstretched arm. This was the view from Eaton Hall, family seat of the artist’s patron, Sir Richard Grosvenor, ancestor of the present 7th Duke of Westminster.

In the top left corner of the canvas, a resident of Derbyshire would recognise Creswell Crags, and anyone else remotely familiar with Stubbs’ paintings might identify a particular limestone formation he used repeatedly whenever savage sublimity of background was to be indicated. Over on the right, the stag is as artificial an adjunct to the foreground group as the amalgamated landscape background. In 1882 one of Pigot’s descendants had the second animal painted out of the picture because he thought it unconvincing and detrimental to the composition. The overpainting was only removed in 1960.

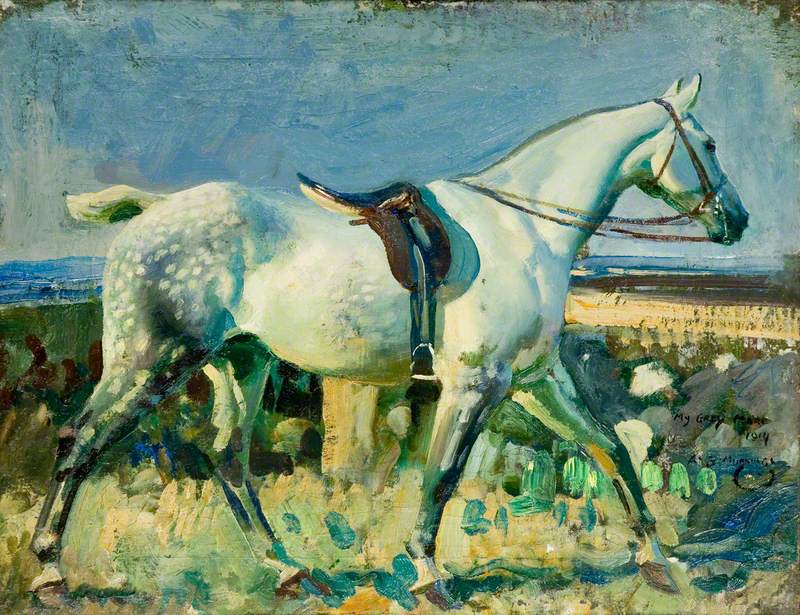

A Grey Hunter with a Groom and a Greyhound at Creswell Crags

c.1762–4

George Stubbs (1724–1806)

But there is nothing either artificial or contrived about the cheetah and its keepers. In an age when foreign visitors were pictured at best as colourful exotics, at worst as sinister or ridiculous caricatures, Stubbs endowed the servants with a grace, nobility and authenticity equal to the magnificent creature they care for. Basil Taylor has described them as two of the artist’s finest portraits, ‘rendered without a trace of superstition or European condescension.’ Mildred Archer went further:

'They are perhaps the finest rendering of Indians in British painting and reflect the deep sincerity of Stubbs’ own nature free from all preconceived... notions of the Indian character.'

Cheetahs are no longer to be found wild in the Indian sub-continent. The last three individuals were reportedly shot in 1947 by the Maharajah of Surguja, a man who enjoyed a hunting career in which he was credited with killing a record number of 1,360 tigers. His tally of cheetahs – apart from the last three that fell to his fire – is not known.

Dr Paul O'Keeffe, author and lecturer