Between 2017 and 2021 a dedicated team of Art UK staff and volunteers travelled the length and breadth of the UK to record public sculptures in our streets and parks, at the top of mountains and beside the sea. Many of these monuments have been erected to commemorate people, celebrating their achievements and remembering events which defined their lives.

Admiral Horatio Nelson (1758–1805)

1809

Richard Westmacott II (1775–1856)

What do these artworks tell us about our country's history and who we choose to commemorate?

Over 13,000 outdoor sculpture records, created by Art UK, have been analysed. We found that just over 2,600 of these public sculptures depict or commemorate named, real-life people.

These 2,600 works are not just figurative statues and busts, but include commemorative water troughs and pumps, fountains, clock towers, bandstands, tombstones and obelisks which have been erected in the memory of a named person or to celebrate their life.

What is the proportion of sculptures of men and women?

Of these 2,600 works across the UK, 77.5% are dedicated to men, 17% are dedicated to women and 5.5% are dedicated to both men and women.

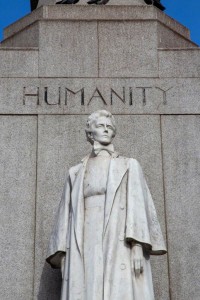

'Rise up, women' (Emmeline Pankhurst, 1858–1928)

2018

Hazel Reeves and Bronze Age Sculpture Casting Foundry

What happens if we just count figurative or pictorial sculptures, such as statues, busts and reliefs, taking out items such as clock towers, fountains and tombstones? The statistics change slightly, with the percentage of sculptures of men increasing: 88% are sculptures of men, 10% are sculptures of women and 2% are sculptures of men and women. This clearly shows that we are more likely to see depictions of men in figurative sculptural form in the UK, than of women.

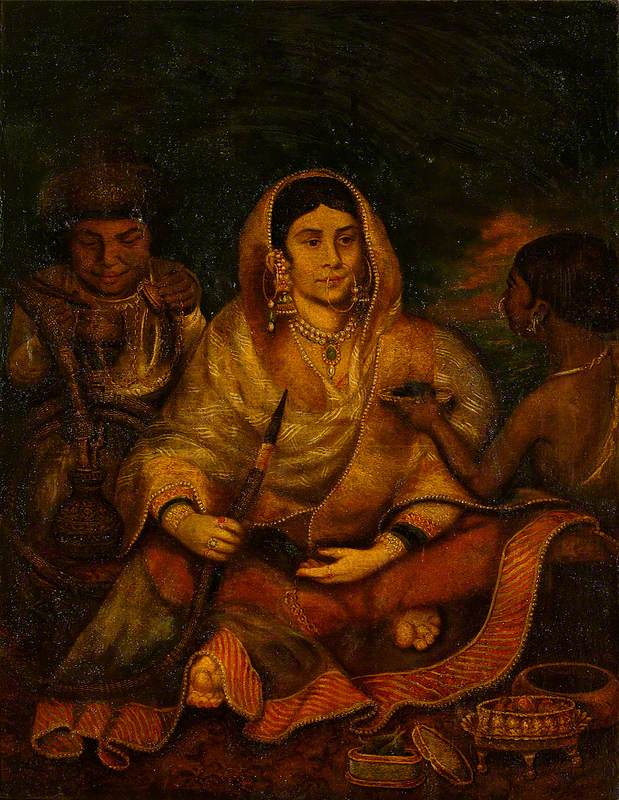

How many sculptures of named people of colour are there?

Just under 2% of the 2,600 artworks across the UK depict or commemorate people of colour.

Examples of people of colour commemorated in public sculptures and monuments include Betty Campbell (1934–2017) MBE, Wales' first black head teacher, in Cardiff...

Betty Campbell (1934–2017), MBE

2021

Eve Shepherd and Castle Fine Arts

...the poet Jackie Kay (b.1961) in Edinburgh...

...and Henrietta Lacks (1920–1951) in Bristol, a Black American woman whose cells were the first ever to survive and multiply outside the body, and whose use changed the course of modern medicine.

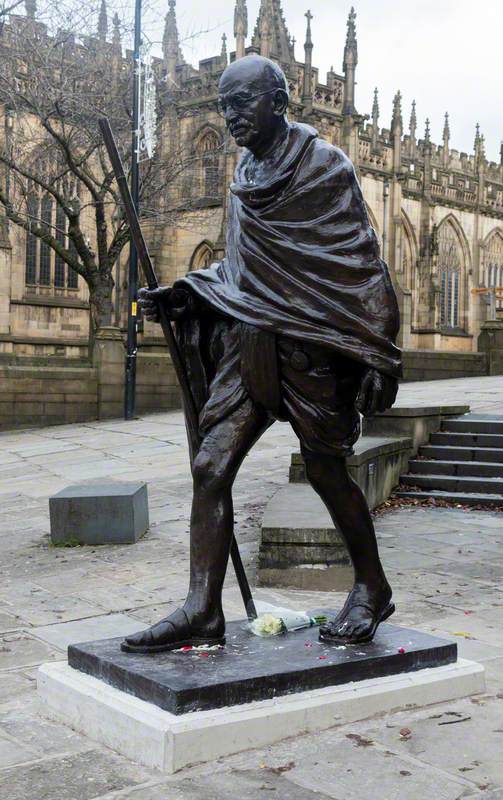

There are no less than five monuments to the architect of Indian independence Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) – in Westminster, Camden, Greater Manchester, Cardiff and Hull...

Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948)

2015

Philip Henry Christopher Jackson (b.1944) and Morris Art Bronze Foundry (founded 1921)

Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948)

2019 (?)

Ram Vanji Sutar (b.1925)

Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948)

2015

Ram Vanji Sutar (b.1925) and Anil Sutar (b.1957)

Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948)

2004

Jaiprakash Shirgaonkar (b.c.1952)

...and two sculptures of anti-apartheid campaigner Oliver Tambo (1917–1993), both in the London Borough of Haringey.

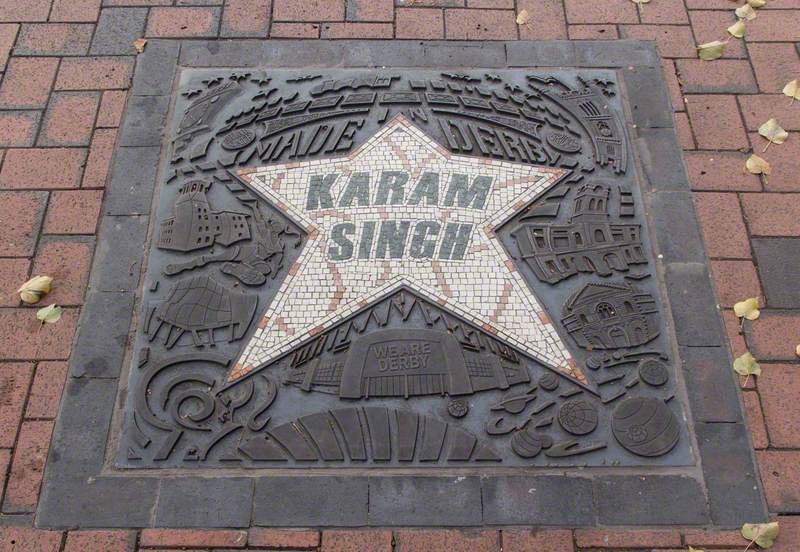

Visitors to Derby can see a star on the Made in Derby Walk of Fame 2 for champion breakdancer Karam Singh (b.1998).

A poignant sculpture in Hull, called True Love, honours two Inuit people, Memiadluk and Uckaluk, who arrived in Hull in 1847 aboard the local whaling ship Truelove.

The following year the married couple set sail for their home in Cumberland Sound, Baffin Island. During this journey, Uckaluk died following an outbreak of measles on board the ship.

A statue of the Native American woman Pocahontas can be found in Gravesend, Kent (where she died in 1617)...

... and also commemorated in the town is Squadron Leader Mahinder Singh Pujji, one of the first Sikh pilots to volunteer during the Second World War – he became a distinguished Royal Air Force fighter pilot.

Squadron Leader Mahinder Singh Pujji (1918–2010)

2014

Douglas Jennings (b.1966)

In Southwark, Mahomet Weyonomon (1700–1736), a Mohegan Sachem (chief), is remembered in a stone brought from Mohegan lands and carved by sculptor Peter Randall-Page.

Memorial to Mahomet Weyonomon (1700–1736)

2006

Peter Randall-Page (b.1954)

The majority of these sculptures and monuments dedicated to people of colour are sited in England, with fewer in other parts of the UK. That imbalance is being addressed, however, with several artworks having been commissioned and installed in recent years, with plans in place to commemorate more people of colour across the UK.

How many of our public sculptures commemorate royalty?

The largest group of named real people commemorated are royalty, with over 460 public sculptures (15.5% of the total sculptures of named people). These range from early kings and queens, such as King Alfred the Great (of Wessex) and Robert the Bruce (King of Scots), to our present monarch.

Alfred the Great (849 AD–899 AD)

1901

Hamo Thornycroft (1850–1925)

Robert the Bruce (1274–1329)

1877

George Cruikshank (active 1877) and Andrew Currie (1812–1891)

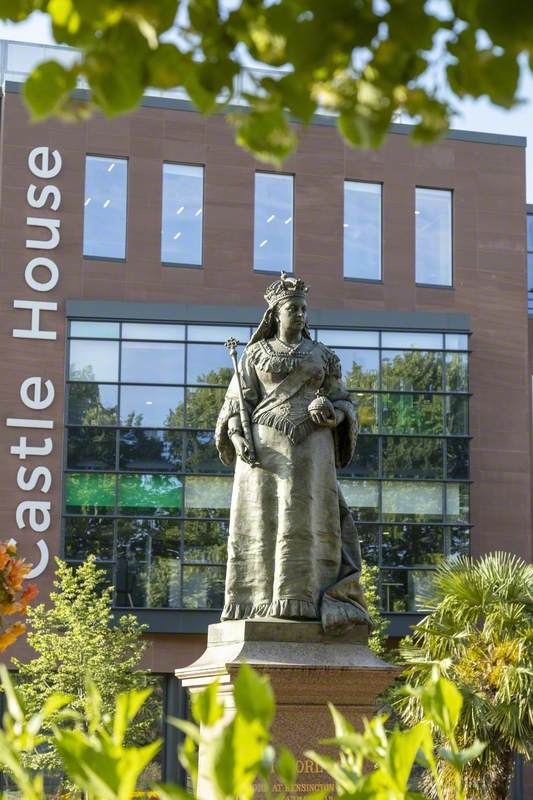

Queen Victoria is the monarch with most public monuments and sculptures dedicated to her, with over 175 statues, fountains, bandstands, clock towers and other artworks erected in her name.

That's 38% of the monuments to royalty across the UK. Most of the monuments to Queen Victoria are in England, but they can also be found in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Channel Islands.

What other roles and professions are depicted in public sculpture?

After royalty, other roles and professions depicted and commemorated in large numbers are military figures (7% of the total sculptures of named people), politicians (6.5%), writers and poets (6.5%), religious figures (5%) and aristocracy (2.5%). The percentage for aristocracy may look low, but many members of the aristocracy are counted in the politicians and military figures percentages listed above, as they frequently held multiple positions in public life.

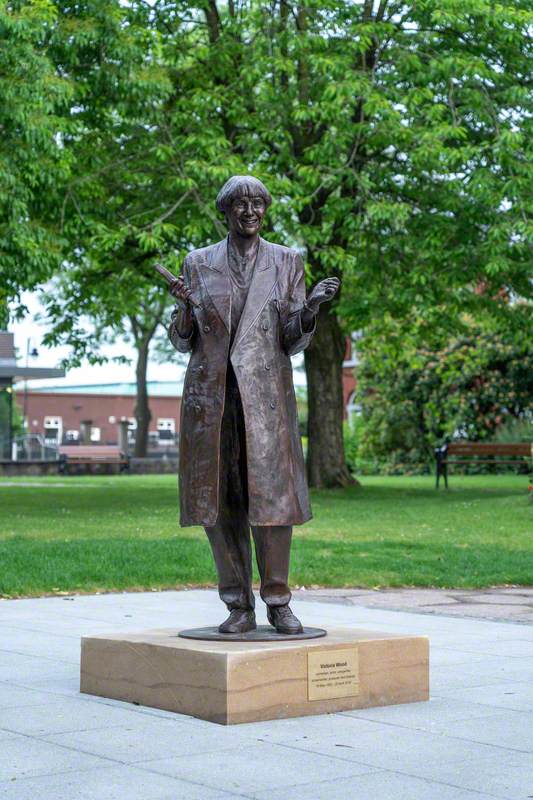

Also well represented is medicine, with statues of doctors and nurses, for example, and people who developed new medical technology, musicians and singers, engineers, artists, explorers, mayors, inventors, actors and comedians. For sporting stars, football comes out on top with the most sculptures and monuments, with footballers and club managers representing 2% of the total sculptures of named people.

More unusual roles and people are commemorated in sculpture across the UK. Examples include smuggler and fishwife Dolly Peel (1782–1857), in Tyne and Wear...

...circus acrobats The Great Blondinis, in Swindon...

...draughts champion Robert Stewart (1873–1941), in Kelty, Fife...

...Cushy Glen, the Highwayman, in Limavady, County Londonderry...

Cushy Glen, the Highwayman

2012

Maurice Harron (b.1946)

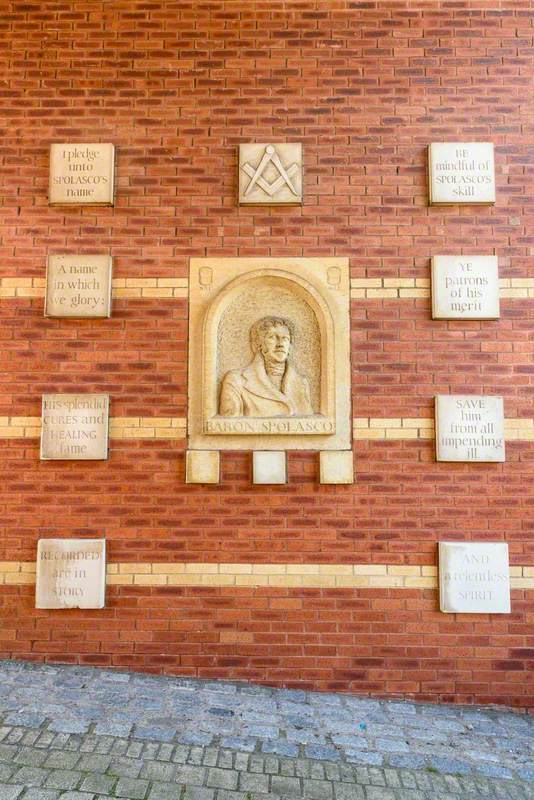

...and Baron Spolasco, a fraudulent doctor, in Swansea.

An abstract sculpture in Tyne and Wear remembers a local miser and kleptomaniac, Lady Peat...

Lady Peat Sculpture

2009 or before

Pupils of Herrington Primary School

...and at Pendle Hill, Lancashire, Alice Nutter (d.1612), a woman accused of witchcraft, is memorialised.

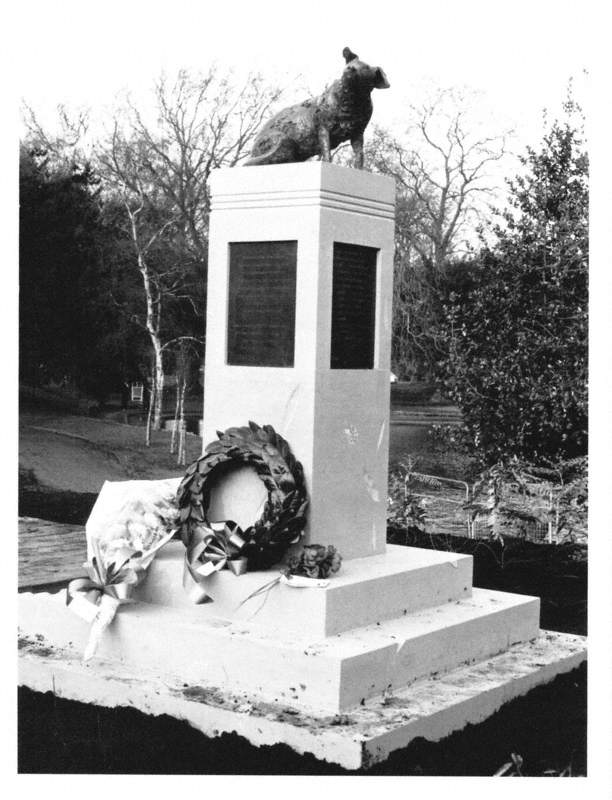

Sadly, many monuments have been erected to commemorate people who have died in tragic circumstances, reminding us that public sculptures can often be a way for people to express their grief and remember a loved one who is no longer with them. Some sculptures honour people who died during a heroic act, such as trying to save others from drowning or a fire.

Heart-breaking public sculptures include the memorial bench dedicated to two Manchester Arena bombing victims in Tyne and Wear, and the Alice Maud Denman and Peter Regelous Memorial Drinking Fountain in Tower Hamlets, which commemorates the people who were killed in a fire at 423 Hackney Road on the night of 19th/20th April 1902 trying to save the lives of the occupants.

Alice Maud Denman and Peter Regelous Memorial Drinking Fountain

1902–1903

J. Whitehead & Sons Ltd (active 1880–1985)

One more unusual monument, in Northumberland, was built as a memorial to what could have been a fatal accident. Miss Baker-Cresswell was driving a pony and trap up to a level crossing when a steam train, which should have slowed down because of the dip in the railway line at Chathill, frightened the horse and she was thrown from the trap. She escaped serious injury and being of a religious disposition she put this down to divine intervention. She commissioned a stone drinking fountain to commemorate the incident.

What do public sculptures tell us about our national identities?

The statues and monuments erected across the UK can tell us a lot about the local area, with each part of the UK reflecting its own identity, industries and local heroes.

England

There are significantly more public sculptures and monuments in England than in other parts of the UK. Of the 13,600+ recorded by Art UK, over 78% are in England. This is unsurprising, with England having a higher population density and more towns and villages than other parts of the UK.

There is also a slightly higher percentage of monuments dedicated to women in England. Of the 10,300 sculptures dedicated to people in England, 75% are dedicated to men, 18.5% are dedicated to women and 6.5% are dedicated to men and women.

The percentage of monuments dedicated to people of colour is slightly higher in England too, at 2.3% of the overall number of named people. The percentage for the UK as a whole is under 2%.

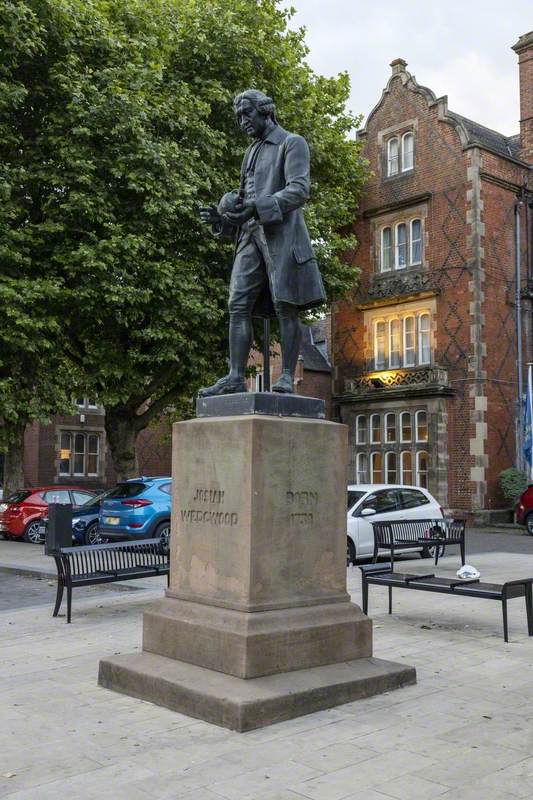

Local industries are represented in sculptures, such as pottery manufacture in Stoke-on-Trent, with statues of Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795), Colin Minton Campbell (1827–1885) and Sir Henry Doulton (1820–1897)...

Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795)

1862

Edward Davis (1813–1878)

Colin Minton Campbell (1827–1885)

1887

Thomas Brock (1847–1922)

Sir Henry Doulton (1820–1897)

1986

Colin Melbourne (1928–2009)

...textile manufacturers in Greater Manchester, with monuments to John Kay (1704–c.1779), Sir Benjamin Dobson (1847–1898) and Robert Owen (1771–1858)...

Sir Benjamin Dobson (1847–1898)

1900

John Cassidy (1860–1939)

...and urban planners of Hertforshire towns Welwyn Garden City and Letchworth, with Sir Ebenezer Howard (1850–1928) and Sir Theodore Chambers (1871–1957) commemorated.

Ebenezer Howard (1850–1928), OBE

2015

Peter Colvin

Scotland

Many public sculptures in Scotland are dedicated to people who embody Scottish identity, such as poet Robert Burns (1759–1796), military leader William Wallace (1270–1305) and King of Scots Robert the Bruce (1274–1329), all of whom have multiple monuments to them.

William Wallace (1270–1305)

1888

William Grant Stevenson (1849–1919)

Robert the Bruce (1274–1329)

1879

John Hutchison (c.1832–1910)

Jacobite supporter Flora Macdonald (1722–1790) is commemorated in two monuments.

Flora Macdonald (1722–1790)

1897

Andrew Davidson (1841–1925)

There are more monuments to poets in Scotland than in other parts of the UK, with over 40 in Scotland, compared to just over 30 in England. Inventors, golfers and geologists are also more popular subjects for monuments in Scotland.

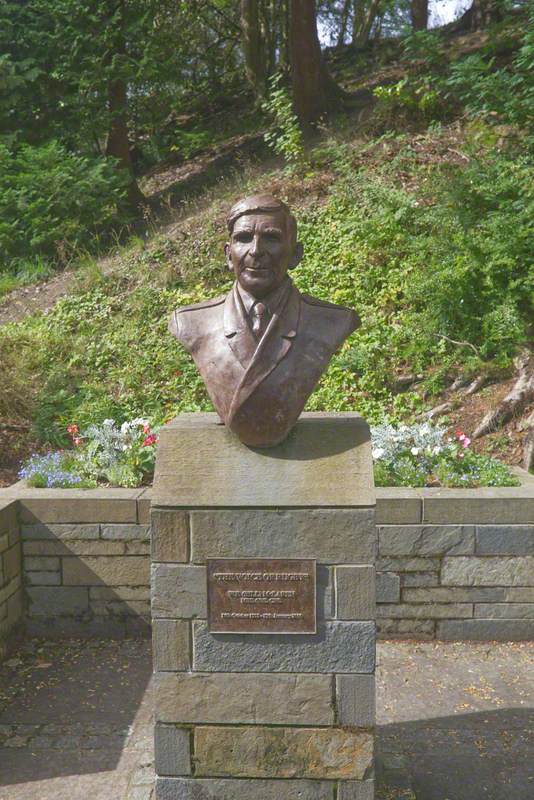

Other notable named people celebrated in public sculptures include rugby commentator Bill McLaren (1923–2010)...

...politician Mary Barbour (1875–1958)...

...photographer Linda McCartney (1941–1998)...

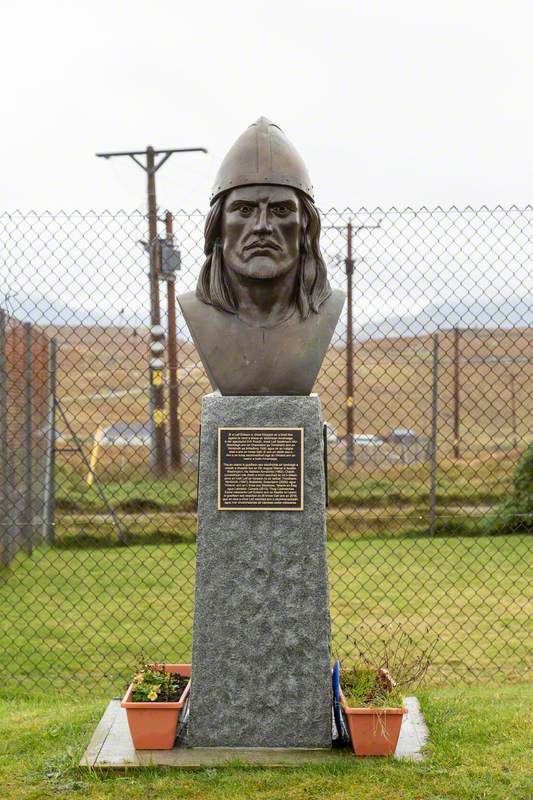

...explorer Leif Eriksson (c.970–c.1020)...

...and Winifred J. Drinkwater (1913–1996), the first woman in the world to hold a commercial pilot's licence.

Wales

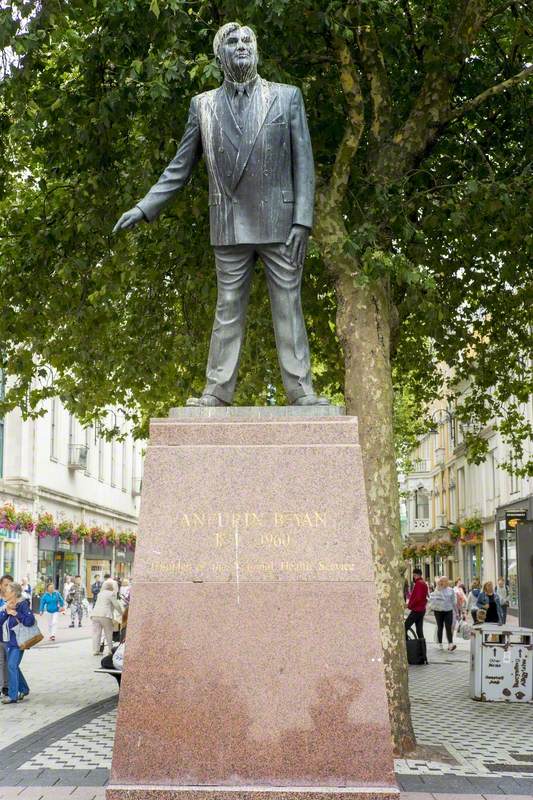

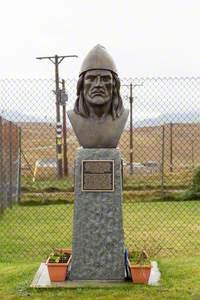

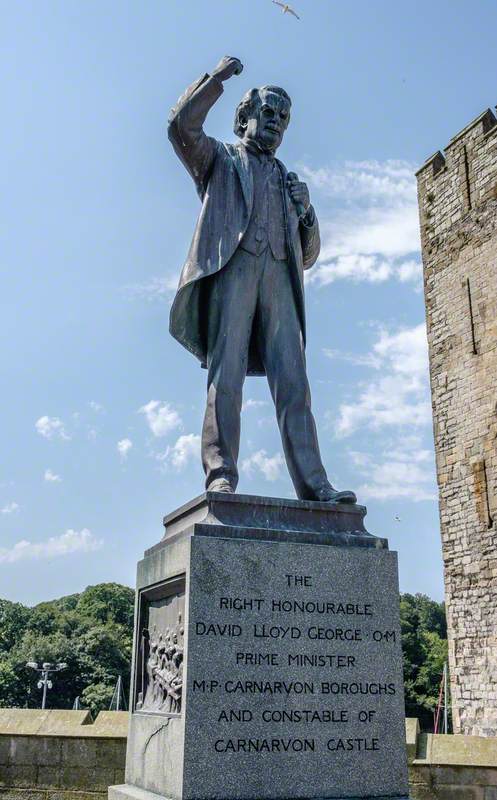

Public monuments in Wales include works dedicated to people who have had an impact on the history of Wales and Great Britain, such as Owain Glyndwr (c.1349–c.1416), Aneurin Bevan (1897–1960) and David Lloyd George (1863–1945).

Owain Glyndwr (c.1349–c.1416)

2007

Colin Spofforth (b.1963)

David Lloyd George (1863–1945)

1921

William Goscombe John (1860–1952) and Thames Ditton Foundry (active 1874–1920)

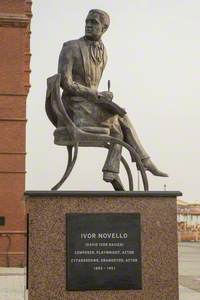

Also commemorated are Welsh writers, poets and actors including Dylan Thomas (1914–1953) (who has several), Ivor Novello (1893–1951) and Elaine Morgan (1920–2013).

Elaine Morgan (1920–2013)

2022

Emma Rodgers (b.1974) and Castle Fine Arts

Northern Ireland

Several political figures are commemorated in Northern Ireland, including Big Jim Larkin (1874–1947), Patrick Rankin (1889–1964) and Sir Robert James McMordie (1849–1914).

Sir Robert James McMordie (1849–1914)

1917–1919

Frederick William Pomeroy (1856–1924)

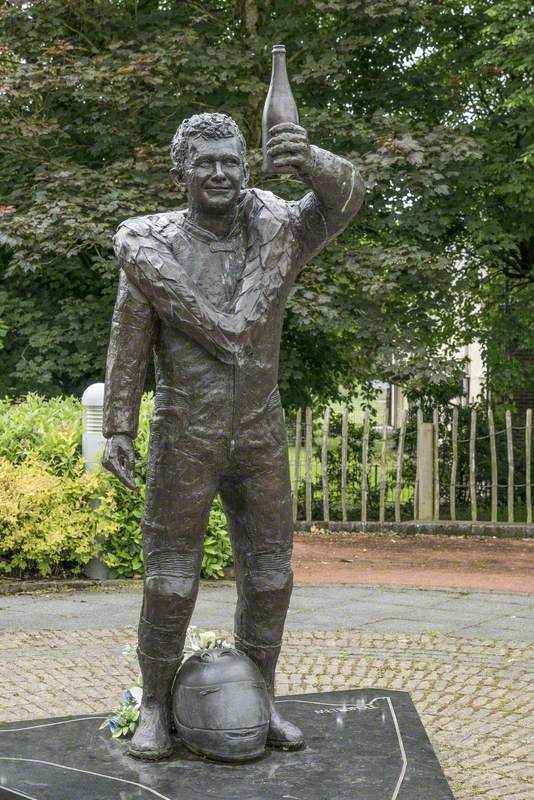

Other people who were born or worked in Northern Ireland and who are celebrated in public sculpture include motorcycle racing brothers Robert Dunlop (1960–2008) and Joey Dunlop (1952–2000)...

...boxer John 'Rinty' Monaghan (1918–1984)...

John 'Rinty' Monaghan (1918–1984), Boxer

Alan Beattie Herriot (b.1952)

...shipbuilder Sir Edward Harland (1831–1895)...

Sir Edward Harland (1831–1895)

1903

Thomas Brock (1847–1922)

...and Ella Pirrie (1857–1929), the first head nurse in the Belfast Union Workhouse Infirmary (now the Belfast City Hospital).

Channel Islands

Public sculpture on the islands includes several monuments to writer Victor Hugo (1805–1885) who lived on Guernsey, and golfer Harry Vardon (1870–1937) who was born on Jersey.

Also represented are monuments to naval crew who lost their lives in the sea near the islands.

Isle of Man

Statues of people associated with the island can be found here, such as The Bee Gees, who were born on the Isle of Man, and George Formby (1904–1961).

Formby's statue depicts him as his character 'George Shuttleworth', a chimney sweep who enters the Isle of Man TT races in George's 1935 film No Limits, which was made on location in the Isle of Man.

Public sculptures of motorcycle racers Steve Hislop (1962–2003) and Joey Dunlop (1952–2000) (which is a second casting of the work in Northern Ireland) also emphasise the importance of motorcycling on the Isle of Man.

Do you have a favourite statue in your local area? Let us know on social media (@artukdotorg) and join our celebration now that we've added over 13,000 outdoor sculptures to Art UK. We'll keep adding more as they are unveiled. The UK's public art changes all the time, and we hope new additions to our streets and squares will continue to reflect the country's diversity and ingenuity.

A huge thank you to the hundreds of volunteers who have made the public sculpture recording such a success, and to Anthony McIntosh and Tracy Jenkins, who managed the whole process for Art UK.

Katey Goodwin, Art UK Deputy Director