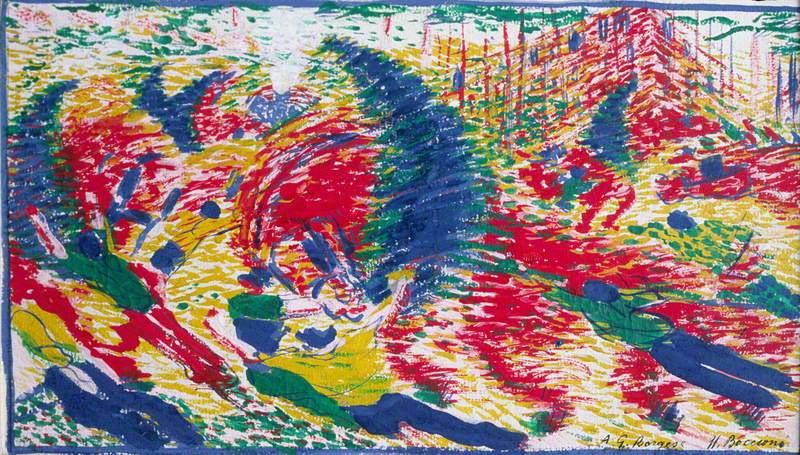

Abstract Speed - The Car has Passed (Velocità astratta - l'auto è passata) 1913

Giacomo Balla (1871–1958)

Tate

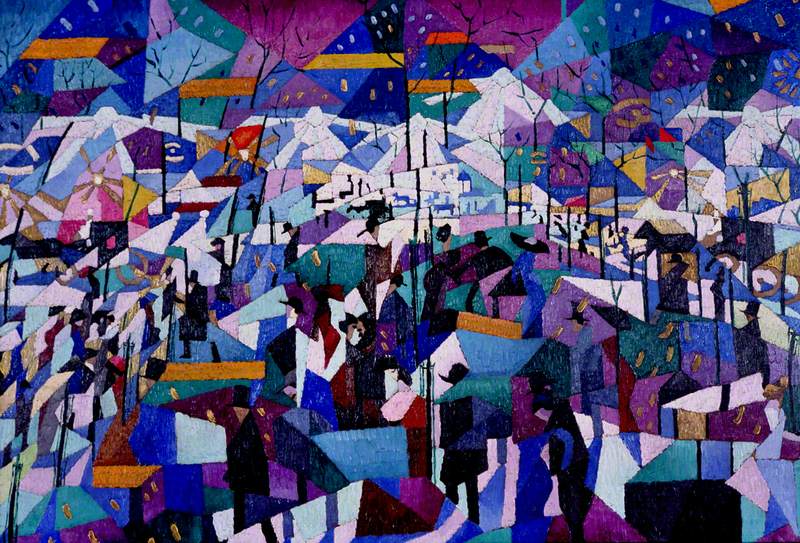

An artistic movement of the early 20th century with political implications, Futurism embraced not only the visual arts but also architecture, music, cinema, and photography. Italian in origin, it expressed the disappointment felt there in advanced artistic and political circles at the apparent lack of progress the country had made since its unification in the mid-19th century. Accordingly, stress was laid on modernity, and the virtues of technology, machinery, and speed were promoted by the Futurists, whose founder was the wealthy poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

He published the first Futurist manifesto in the French newspaper Le Figaro in 1909 and was soon joined by the painters Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini, who all publicly proclaimed their allegiance to the movement in March 1910. This was followed by a technical manifesto a month later and further publications included Boccioni's manifesto of Futurist sculpture in 1912. That year also saw the first proper exhibition of Futurist art, which was widely shown around Europe in Paris, London, Berlin, Amsterdam, Zurich, Vienna, and Budapest. The Futurist style drew on a number of sources, including Neo-Impressionism and Cubism, and favoured faceted forms and multiple viewpoints allied to a sense of movement and speed. Although the movement lingered on in Italy until the 1930s, it was already moribund there by the end of the First World War. It had considerable influence abroad, however, most notably in Russia, where a vigorous Futurist movement sprang up which numbered Larionov, Goncharova, and Malevich among its principal adherents. In Germany the Dadaists learnt from the noisy publicity techniques of the Futurists, as did the Vorticists in England, while in France both Duchamp and Delaunay were sympathetic to the Futurists' promotion of a modern spirit in art.

Text source: The Oxford Concise Dictionary of Art Terms (2nd Edition) by Michael Clarke