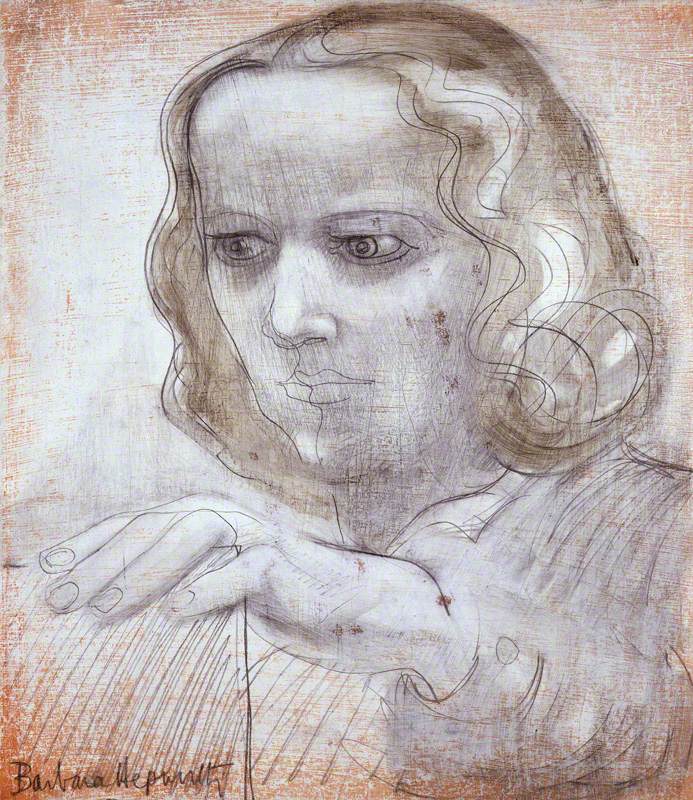

At her death in 1975, Barbara Hepworth was described as 'probably the most significant woman artist in the history of art to this day.' Forty years later, Hepworth was the subject of a major exhibition at the Tate Britain, the first large scale retrospective of the artist's work in London for 50 years.

Hepworth's work has previously been displayed in dedicated venues, such as The Hepworth Wakefield, and her old studio in St Ives, which is managed by the Tate. Inspired by Tate Britain's exhibition, I went out to find the public sculptures in London that constitute part of the legacy of Britain's best-loved, internationally acclaimed, modernist sculptor.

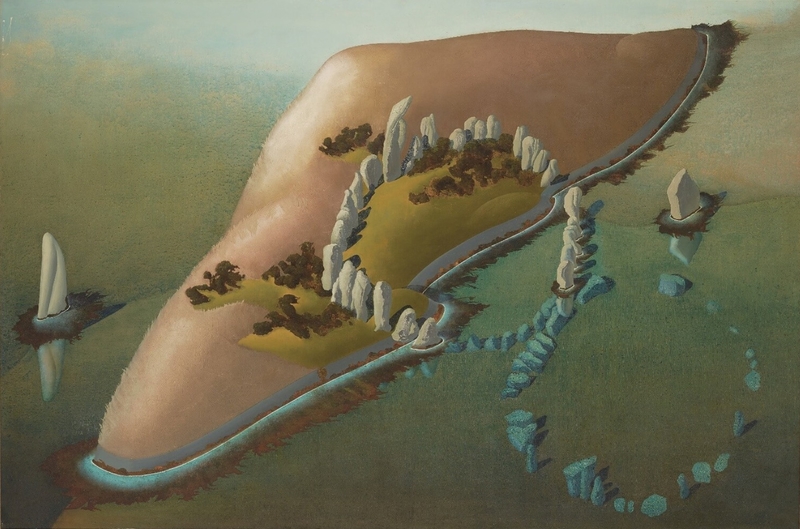

Barbara Hepworth moved to St Ives in 1939 in order to escape a panicked London shortly before the start of the Second World War. Although her arrival was not auspicious, Hepworth admired the 'barbaric and magical countryside' of Cornwall, studded with ancient standing stones and hemmed by dramatic coastal landscapes. Thirty years later, and towards the end of her life, Hepworth declared the area her 'spiritual home'.

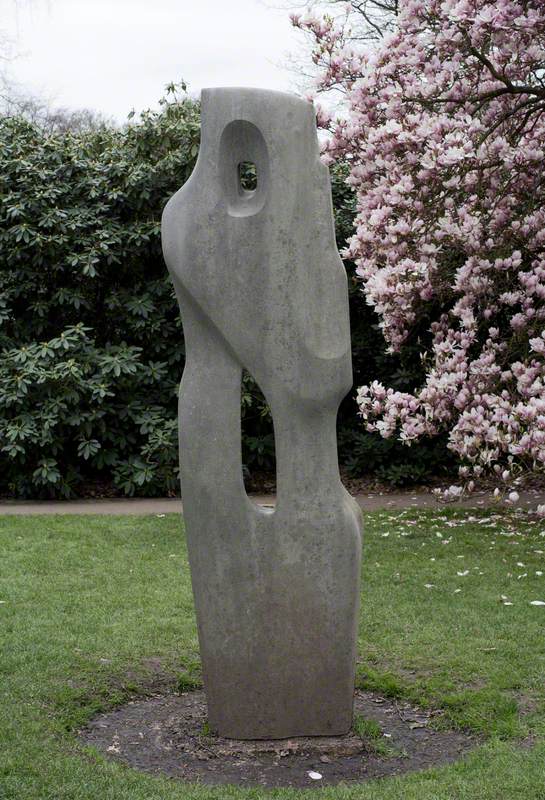

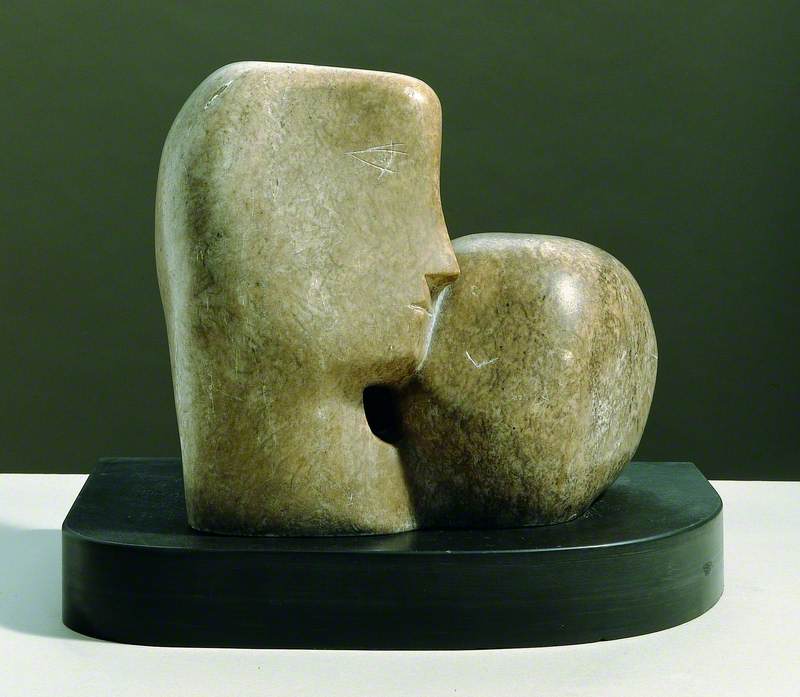

On Hampstead Heath, something of the totemic phenomena of the Cornish landscape has been enshrined among the rhododendron bushes beside Kenwood House. Hepworth's Monolith-Empyrean (meaning 'heavenly stone') is carved from a limestone block rich with fossils.

The sculpture's outline is humanoid, but the viewer is invited to look through and beyond the sculpture by cavities that pierce right through the block, framing shifting perspectives of the gardens. The sculpture used to stand on London's Southbank, but it has occupied its place on Hampstead Heath since it was purchased by the London County Council in 1959.

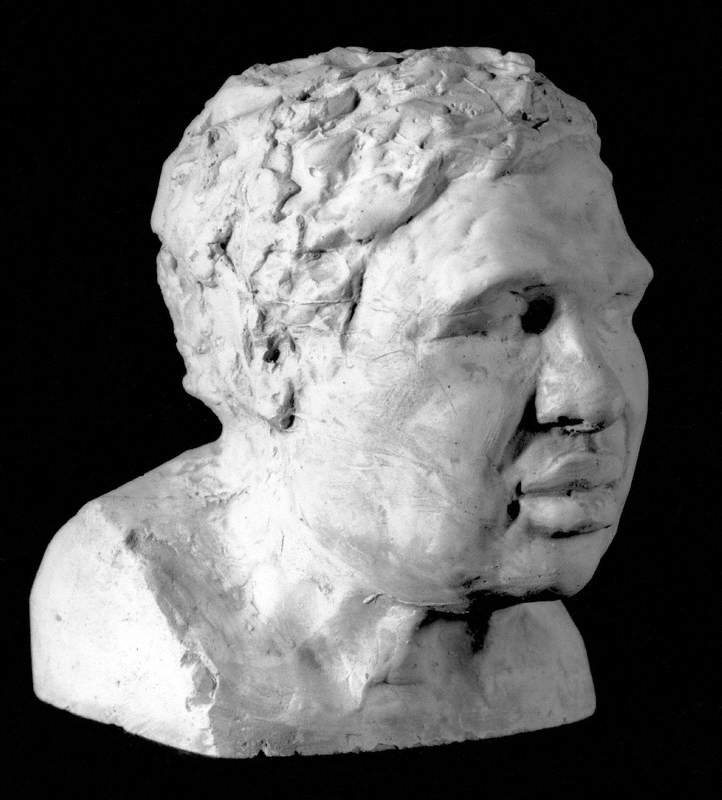

By the early 1960s, Hepworth had established her predominance over the British sculpture scene and her predilection for the monumental was exerting a hypnotic influence on aspiring sculptors. Around this time, my grandmother began studying at art college and on her first day her tutor asked her to choose between painting or sculpture. Without hesitation, my grandmother chose painting. Her reasoning was that, as abstraction and monumentalism were dominating sculptural creation, she did not want to work in a medium that would require her to depend on male students to carry up gigantic, heavy blocks of stone for her from the Central Saint Martins basement!

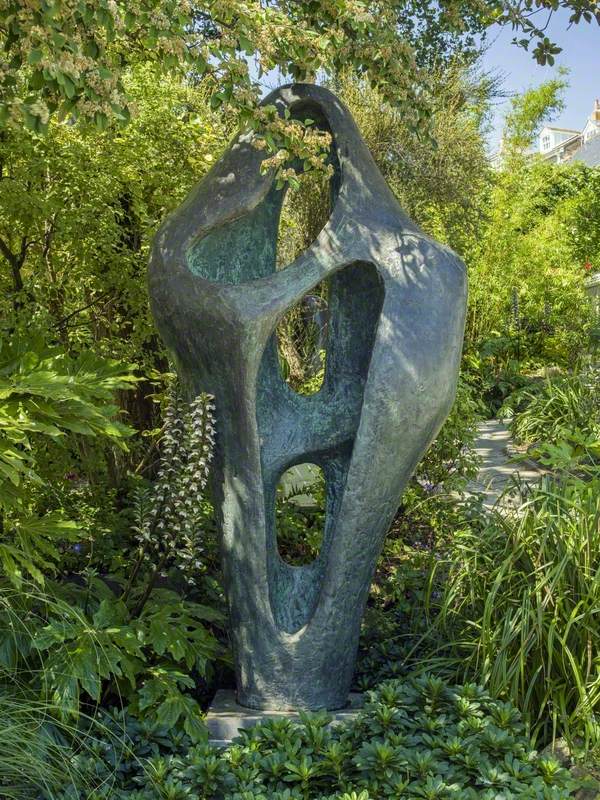

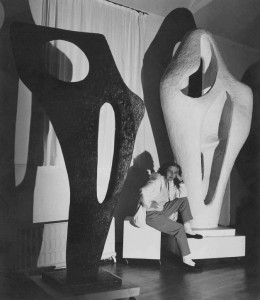

Hepworth's massive Single Form, in Battersea Park, made me think of my grandmother. At over 10 feet tall, the work occupies the outer limits of what can be accomplished in a single bronze casting.

Single Form was constructed as a memorial to Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1952 up until his death in 1961. Hammarskjöld, a good friend of the sculptor, had been speaking to Hepworth about a commission for the UN site just before his tragic death in an airplane crash. Single Form was first exhibited in Battersea Park in 1963. Over the next year, Hepworth recast the sculpture in three parts for the UN building in New York City, scaling the sculpture up from 10 feet to a gigantic 21 feet high.

When interviewed in 1972, in the last few years of her career, Hepworth stated that she thought 'every sculpture must be touched. It is part of the way you make it and it's our first sensibility: the sense of feeling; the first one we have when we are born.'

By contrast, the 2015 exhibition of Hepworth's work at Tate Britain suffered from having Hepworth's sculptures locked away in irritatingly reflective glass cases, and for having instructed its stewards to keep an eagle eye on fingers twitching to caress Hepworth's tactile bronzes. Fortunately, on the front lawns of Tate Britain for the duration of the show stood Figure for Landscape, which was happily exposed for the general public to peer at, prod and stroke it to their heart's content.

This is the second time that Figure for Landscape welcomed visitors into the Tate. In 1968, during the previous large-scale retrospective of Hepworth's work, it was positioned on the front steps of the gallery. Perhaps Penelope Curtis, the lead curator of the 2015 Hepworth exhibition, was giving the nod to the work of her predecessors.

In 1961 John Lewis opened its flagship store on Oxford Street. To celebrate the occasion, and to project a marketable image of urbanity, John Lewis commissioned a sculpture to adorn the plain facade that faces onto Holles Street. Several sculptors entered the competition, including Barbara Hepworth. All of them were rejected. On her second attempt, Hepworth's sculpture Winged Figure was accepted. In 1963, the sculpture was fixed in place.

We’re staying close to home for #WorldArtDay and sharing works from our collection.

— The Hepworth Wakefield (@HepworthGallery) April 15, 2021

The centrepiece of The Hepworth Family Gift is Barbara Hepworth’s prototype for Winged Figure, a commission from John Lewis for their flagship store on Oxford Street in London. pic.twitter.com/KRkRNJUXOh

Barbara Hepworth declared that she thought 'one of our universal dreams is to move in air and water without the resistance of our human legs. If the Winged Figure in Oxford Street gives people a sense of being airborne in rain and sunlight and nightlight I will be very happy.'

The current gleam of the aluminium and stainless steel sculpture is due to a recent restoration.

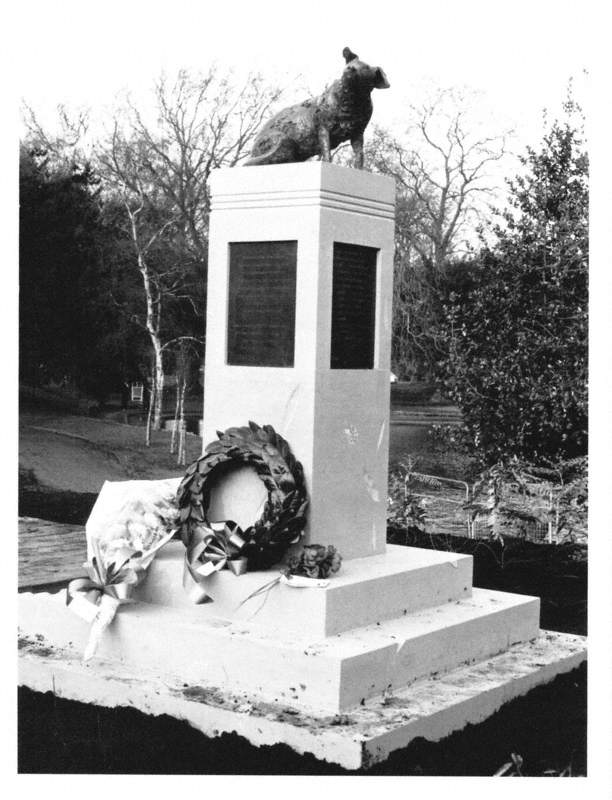

There used to be a fifth Barbara Hepworth sculpture in London. Two Forms (Divided Circle) used to stand in Dulwich Park, but it was stolen by suspected metal thieves in 2011.

Fortunately there are other versions of it across the country, including this one at Tate St Ives.

Victoria Ibbett, writer