The Edwardian era, which came to an end as the new decade began (Edward VII died in 1910), and its immediate aftermath, was a time of violent clashes between the classes and sexes. This was a time of strikes, civil unrest and militant suffrage activism.

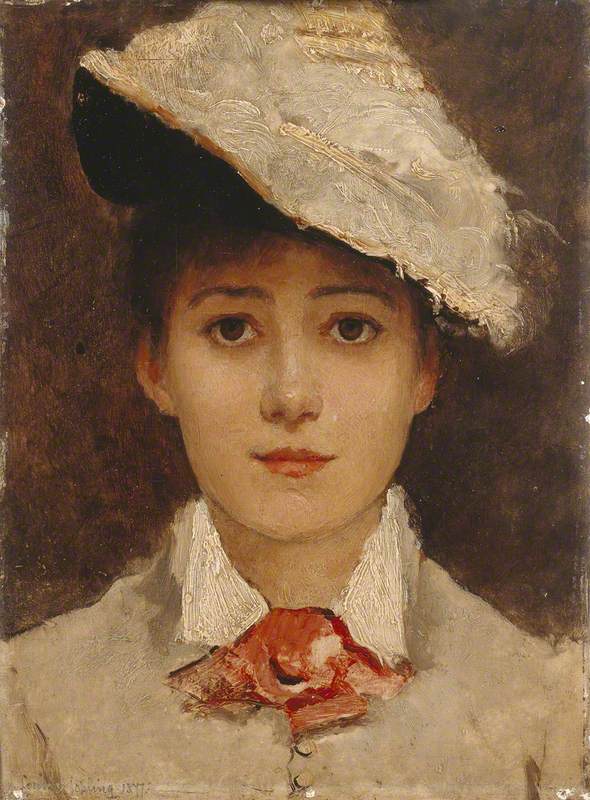

Surveillance Photograph of Militant Suffragettes

1914

Criminal Record Office (active since c.1914)

The First World War, which shattered the social and cultural landscape, was preceded by a sense of conflict between the status quo and new ways of being, understanding and representing the world played out in art, reflected by the rapid founding, and vociferous arguments between, new avant-garde movements.

A growing dissatisfaction with what some artists regarded as the 'conventional niceties' of the academic style – epitomised by the Royal Academy exhibitions with their 'safe' subject matter and polished, figurative approach – led to a proliferation of small groups before 1914. Each one proclaimed that they carried the torch for radical artistic progress, and while some women artists were members and treated as equals, they were often sidelined or excluded.

For Sylvia Gosse, the idea that her art should be influenced by the most modern work in France, uniting a more direct painterly approach with a gaze upon the truth of ordinary subjects rather than the acceptably picturesque, meant that she was aligned with the Fitzroy Street Group.

Founded in 1907, the group centred on the work of Gosse's friend and colleague Walter Sickert, alongside artists such as Spencer Gore, Walter Russell, Robert Bevan and William Rothenstein among others.

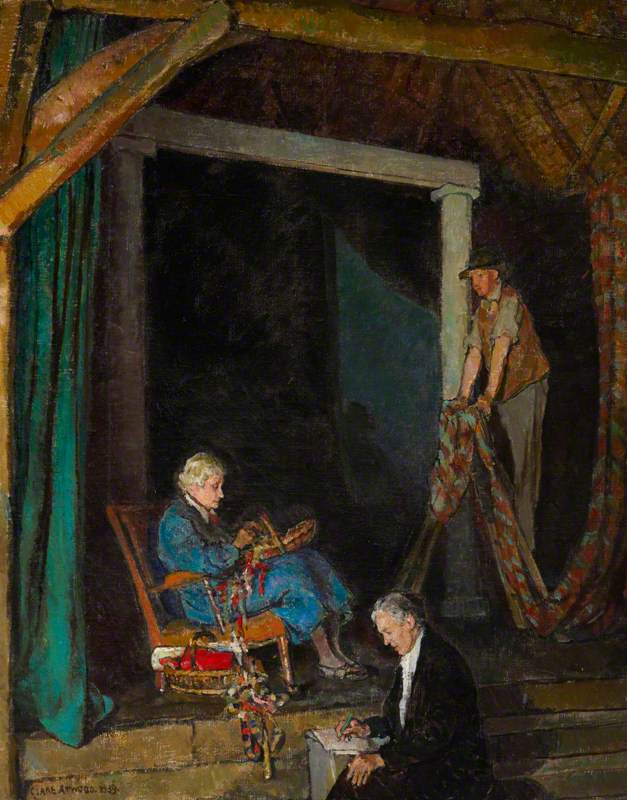

Her subjects included women at work: The Seamstress (c.1914) and The Printer (c.1915). Gosse trained at the Royal Academy before becoming co-principal of Sickert's art school at Rowlandson House, Hampstead. More about the artist's life and artistic career can be read in 'Sylvia Gosse: being modern.'

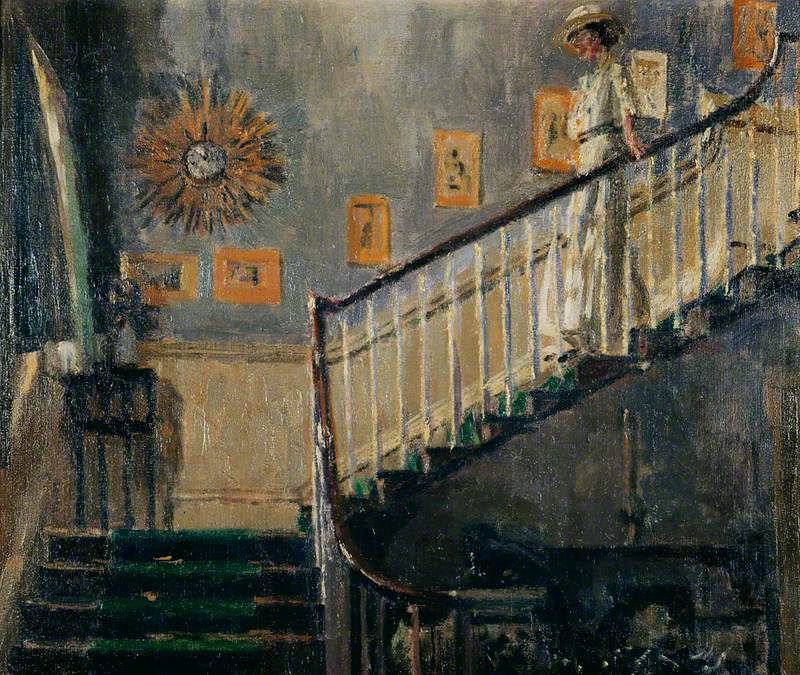

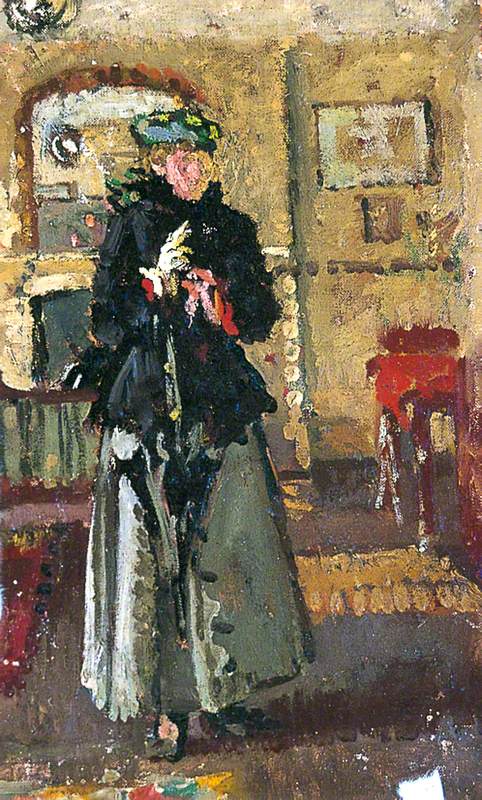

Also part of the Fitzroy Street Group were the American artists Anna Hope 'Nan' Hudson and Ethel Sands, who began their lifelong partnership while training in Paris, both studying under the painter Eugène Carrière. The two women were largely known for their paintings of interiors and quiet domesticity.

Ethel Sands Descending the Staircase at Newington

c.1920

Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942)

Reflecting their friendship with Walter Sickert, Sands had captured Tea with Sickert sometime between 1911 and 1912.

When the Fitzroy Street Group members reconfigured as the Camden Town Group in 1911, they decided to be men-only. Radical experimentation did not necessarily mean radically new gender relations, and for some avant-garde artists, women artists were associated with the tame tastefulness that they were trying to destroy.

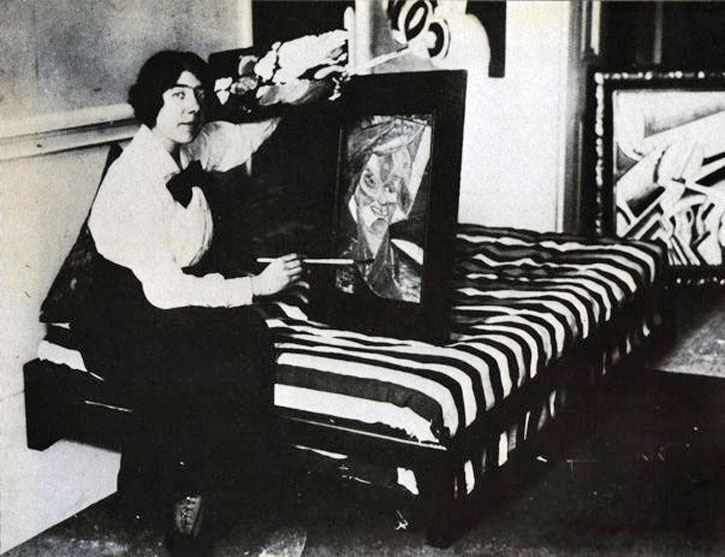

However, the group that formed around Wyndham Lewis in 1913, the Vorticists, saw things differently. The artist Kate Lechmere had instigated and bankrolled the Rebel Arts Centre in London where the idea of Vorticism first emerged. Sadly her work has long since disappeared, and the only surviving record of her painting that remains is in one photograph of her at her easel.

Kate Lechmere posing with her painting Buntem Vogel at the Rebel Art Centre

March, 1914, by unknown photographer published in the Evening Standard

When Vorticism emerged, announcing itself with a manifesto and its own magazine, Blast, two women were founder members: Helen Saunders and Jessica Dismorr. The two women, depicted standing slightly apart from the group in the open doorway, were featured in William Roberts' recreation of the group in The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel: Spring, 1915.

The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel: Spring, 1915

1961–2

William Patrick Roberts (1895–1980)

Vorticism, with great panache, humour and violent language, sought to destroy the status quo in art and society, allying a fractured, hard-edged experimental style that embraced abstraction with incendiary writing. In Blast, they published a list of those they wanted 'blasted' (including all those connected with the Royal Academy) and those they 'blessed', including the suffragettes, whose violent tactics they approved of.

Very few of Dismorr's Vorticist works have survived, but they include the astonishing floating forms of Abstract Composition (c.1915), a dreamscape of vast unmoored man-made constructions, and her prose poems describing her exploring city spaces alone. More about Dismorr can be read in 'Jessica Dismorr: the radical pioneer of Vorticism.'

Her close friend Saunders, meanwhile, also wrote poetry, and painted watercolour and ink compositions, uniting razor-sharp line with an often dazzling sense of colour. It is worth remembering, however, that for women artists being politically radical did not mean that your art was necessarily avant-garde.

The suffrage campaigner Lily Delissa Joseph painted what may seem technically and compositionally academic paintings (she was known to be an admirer of Rembrandt). Her 1906 Self Portrait with Candles in the Ben Uri Collection reflected her artistic emphasis on her Jewishness, though it was her active involvement with the Women's Suffrage Movement that ultimately prevented her from attending her own private view at the Baillie Gallery, London in 1912, when she was briefly imprisoned in Holloway Prison for her activism.

At the outbreak of the First World War, fewer artistic opportunities for artists meant that women artists often abandoned their own work, or put down their paintbrushes completely. Helen Saunders spent most of the ensuing five years working in the Censor's office, while Jessica Dismorr worked as a nurse in France and thereafter suffered a nervous breakdown. Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson went to Dieppe to set up a hospital for wounded soldiers.

The conflict altered the art world irrevocably, and there were few opportunities for exhibiting, or for selling work. Among those fortunate enough to earn a government commission to paint wartime subjects, there were very few women artists. The few women artists who were commissioned by the government were not given salaried roles as official war artists, but rather paid for individual works. Two of the women who won commissions were Flora Lion and Anna Airy. Lion made two paintings both dated to 1918, including the Women's Canteen at Phoenix Works, Bradford and Building Flying Boats. Her paintings were magnificent, yet there was a mysterious demurral over payment, and in the end, both works were donated to the museum rather than purchased.

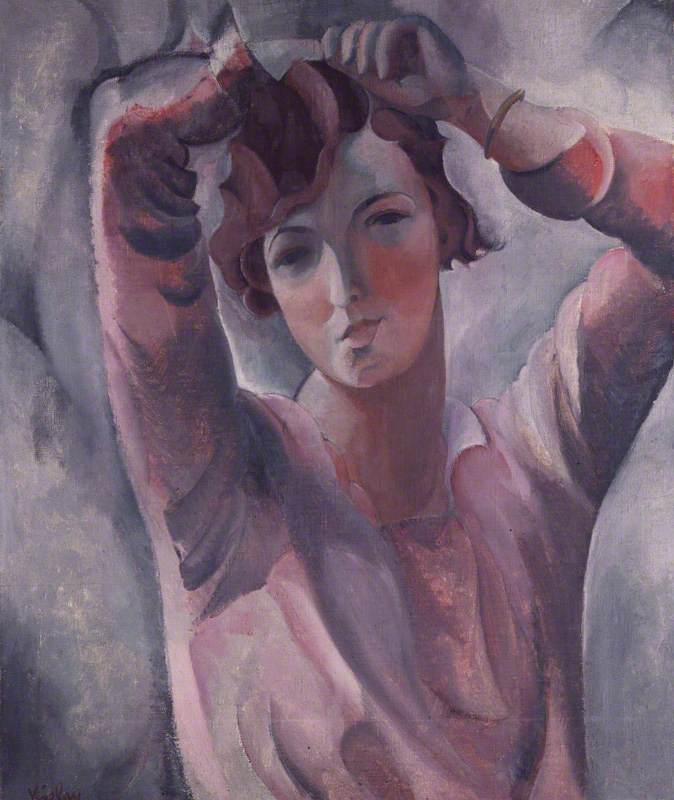

Shop for Machining 15-Inch Shells: Singer Manufacturing Company, Clydebank, Glasgow

1918

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

Airy also suffered from a difference in treatment, most likely due to her gender. For painting four 'typical scenes' in munitions factories, including this view of shells being made at the Singer factory in Glasgow, her contract was unusually stringent and punitive. While both Lion and Airy's paintings may well have been perceived by their avant-garde contemporaries as dully conventional, they can also be perceived as ground-breaking in their subject matter.

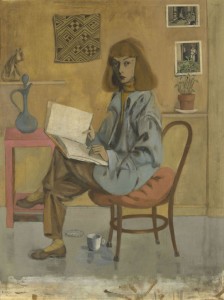

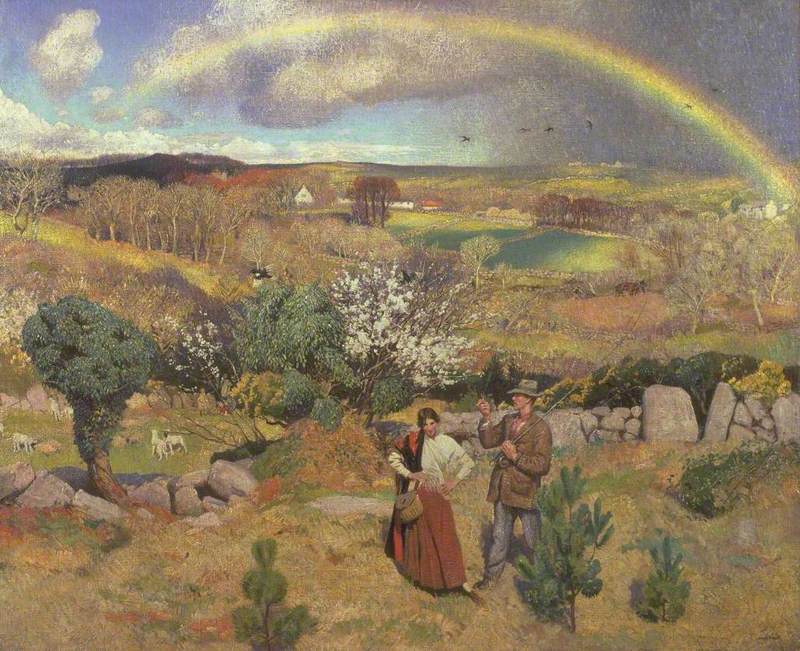

In Laura Knight's painting Spring, a beautiful young woman stands with a man in a landscape illuminated by brilliant sunlight.

Painted during a time of violence and devastation, Knight's Spring may well have offered a vision of solace and hope – a view of a paradise that had survived and could be regained in the fields of England. Knight's work also reflects a shift in appetite; as the war continued, the aggressive iconoclasm of pre-war avant-garde styles was no longer as favourable.

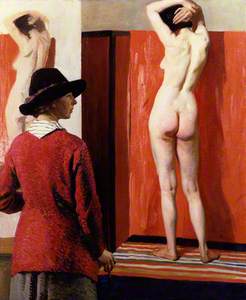

The female model in Spring is Ella Naper, who also posed for one of Knight's best works, Self Portrait, The Model, a painting expressed in Knight's virtuosic academic style.

It was no coincidence that the end of the war coincided with the partial granting of the right to vote for women in Britain, with the passing of the 'Representation of the People Act' on 6th February 1918.

It would have been difficult to deny the contribution women made during the conflict: as factory workers, farm labourers, nurses and ambulance drivers at the front dealing directly with the horrific consequences of war. No longer could the government use the excuse that women were too fragile to engage fully with the world of work, nor that they should be barred or 'protected' from the rough and tumble of politics. The proviso was that in order to vote a woman would have to be over 30 and a householder to be emancipated, which meant that one-third of women remained excluded and equality not quite achieved.

Nevertheless, the vote was a sign of progress, one which would also improve the lives of women artists. Amid the atmosphere of loss in 1918 – and the mammoth effort to rebuild and repair – there was for some women a sense of new unprecedented freedom in the still-young century.

Alicia Foster, curator

.jpg)