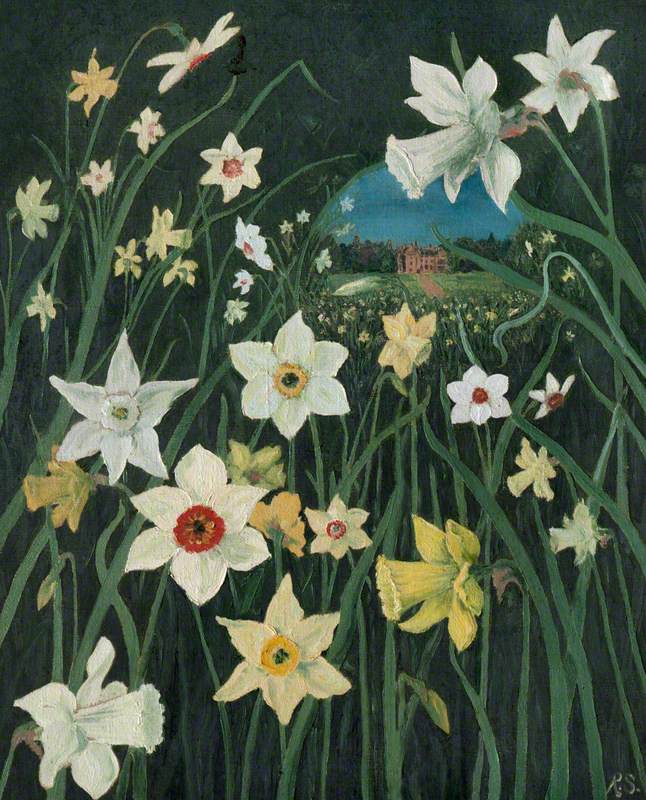

Bunches of tulips lying on a table, a bowl of delicate violets, a green glass vase bursting with colourful, loosely painted peonies. These are the subjects of just some of the paintings by local female artists in the collection at Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum and in the museum's current exhibition 'Outgrowing: Flowers and female artists, 1700 to Now' (until 24th April 2022).

The paintings are skilled works of art and reveal a great awareness of the schools of artistic thought that were popular at the turn of the twentieth century in Britain. However, beyond this, we cannot say much about the artists, as there is little biographical information.

Elizabeth Whitehead, Emily Ledbrook and Florence Engelbach are not names that are nationally recognised, although Leamington residents may recognise Whitehead's name from her blue plaque on Willes Road in the town. We know the dates they were living, that they showed their works at various local galleries and at the Royal Academy, but, like many female artists, beyond this, we have very little historical record.

When thinking about how to exhibit these works, I wanted to find a way to say more about these female artists. Without much information about their lives, I feared they might be passed over as attractive but ultimately decorative artworks.

The relationship between these women and their subject matter, and why they were drawn to paint flowers, seemed to be the perfect way to unlock some of the deeper meaning behind these works. By setting them in a narrative of 300 years of female floral art, we could explore the unique connection women artists have had with this subject as a vehicle of liberation and expression.

Flowers have often been used as a symbol of femininity, representing the characteristics that have historically been associated with the 'ideal' woman, such as naturalness, romance, and beauty. However, it was also these qualities that were used to justify the exclusion of women from professional and intellectual pursuits, including in the arts and sciences, which were considered to be beyond women's understanding and irrelevant to their domestic role.

For both scientific and artistic purposes, the study of flowers was encouraged as a harmless activity that helped women pass the time, appreciate God's creation of the natural world, and focus their supposedly innate aptitude for decoration.

During the late seventeenth century and early eighteenth centuries, a fascination for natural philosophy swept across Western Europe. Whilst many avenues of scientific enquiry were closed to women, natural philosophy was seen to be an appropriate pursuit as it encouraged womanly virtues such as sensibility, humility, and piety.

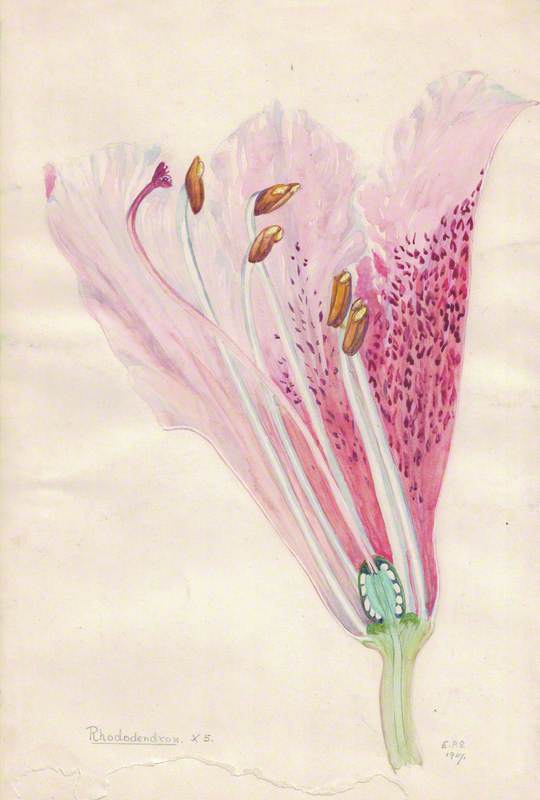

Botany, in particular, was taken up by women of leisure who could grow, study, and depict plants from the comfort of their homes. Botany continued to be a popular pursuit in the Victorian period and the printing of accessible botanical books allowed the study of plants to spread among upper and middle-class women.

Despite society's expectations, many women made significant contributions to the fields of art and botany, gaining public recognition and professional success. Many women used their skill in this field to gain recognition as botanical illustrators in scientific circles, particularly from institutions such as the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew.

Botanical study played an important part in the work of many professional female artists, like Mary Moser (1744–1819) and Margaret Meen (1751–1834). Meen worked as a drawing instructor to the daughters of George III and Queen Charlotte as well as publishing Exotic plants from the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew in 1790.

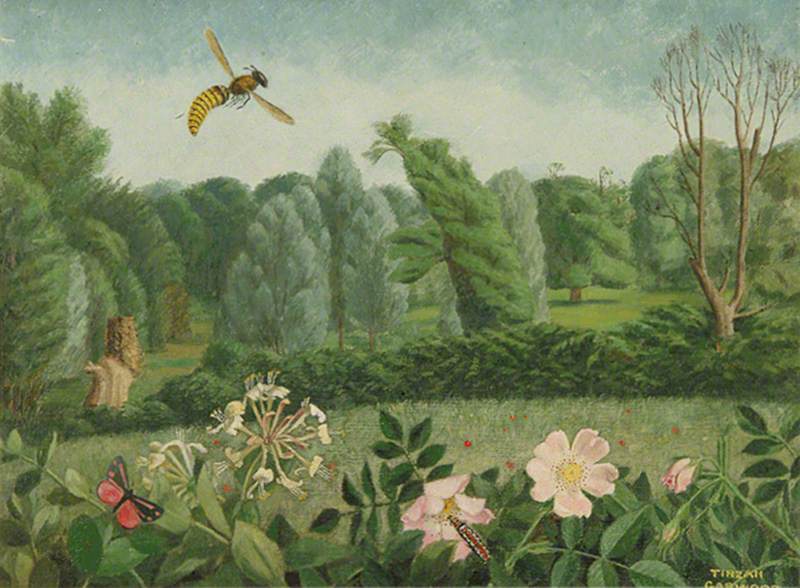

Whilst supposedly a safe subject that could be pursued at home, some women used their botanical studies to break the societal limitations placed on them and travel abroad. Artists such as Maria Sybilla Merian (1647–1717), Marianne North (1830–1890) and Margaret Mee (1909–1988) travelled across the globe to capture and record flora and fauna as far afield as South America, Indonesia and Africa.

A Brazilian Climbing Shrub and Humming Birds

c.1873

Marianne North (1830–1890)

Merian's achievements both as an artist but also as a seventeenth-century woman were remarkable. Having divorced her husband, she travelled alone with her daughter to the then Dutch colony of Suriname in 1699 to study and record the insects of that region and the plants they lived on.

Following in Merian's steps less than 200 years later, Marianne North travelled across the world almost always on her own, between 1871 and 1885. Both artists broke boundaries in scientific illustration. Rather than painting a sample against a plain background, Merian depicted the habitat in which insects lived. Similarly, North captured the wider environment of the plants she illustrated. North's works in particular were ground-breaking as she used oil paint rather than watercolour to give a sense of atmosphere and place to her botanical illustrations.

Water-Lily and Surrounding Vegetation in Van Staaden's Kloof

c.1882

Marianne North (1830–1890)

As botanical science became increasingly professionalised in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many amateur women began to be excluded from its study. However, artists like Matilda Smith (1854–1926) and Lillian Snelling (1879–1972) were able for the first time to pursue their work professionally and continue to contribute to the field.

After working as a botanical artist at @thebotanics, Lilian Snelling was employed by the RHS to illustrate over 700 plants for Curtis’s Botanical Magazine. She was awarded a Victoria Medal of Honour in 1955 & some of her paintings are in the @RHSLibraries art collection. #IWD2019 pic.twitter.com/s6vE2xfKne

— The RHS (@The_RHS) March 8, 2019

Beyond the world of botany, female artists were still closely bound to the subject of flowers. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the male art establishment did not consider the majority of women to have the capacity for producing high art, the pinnacle of which was history painting. They did, however, consider women to have the capacity for good taste and thus actively encouraged them to work on decorative subject matter.

The ability to paint and draw flowers was seen to be a positive accomplishment for upper- and middle-class women and an appropriate way for them to pass their leisure hours. Such views were often shared by women themselves, who viewed their work as a pastime not to be publicly exhibited or sold.

Many female artists also turned to the subject of flowers because entrance into art schools was not generally possible for women until the mid-nineteenth century and they were prohibited from learning life drawing. Flowers could be easily observed and depicted at home without the need for specialist training, unlike figure drawing.

Despite these limitations, many women achieved professional and commercial success as flower artists during this period. Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750) is perhaps one of the most famous flower painters of the seventeenth-century Netherlands. Such was her success in this field that she became the first female member of the artist's society, Confrerie Pictura and from 1708 to 1716 she served as the court painter to Johann Wilhelm, the Elector Palatine of Bavaria.

In eighteenth-century Britain, Mary Moser became one of only two female founders of the Royal Academy in 1768 and earned the patronage of George III and Queen Charlotte, creating a vast decorative scheme for Frogmore House in Windsor. Moser's portrait by George Romney shows Moser claiming her space amongst her male contemporaries, painting in the medium of oils, rather than watercolour, the traditional choice for female botanical artists.

Throughout the nineteenth century, female painters and watercolourists displayed their works at public exhibitions, including the Royal Academy, capturing the Victorian taste for the natural world. However, the pressures of domestic duties, lack of dedicated workspaces or resources and the association of the 'decorative' which lingered over their work has meant that their careers were not always straightforward. Many of their stories have been lost to history.

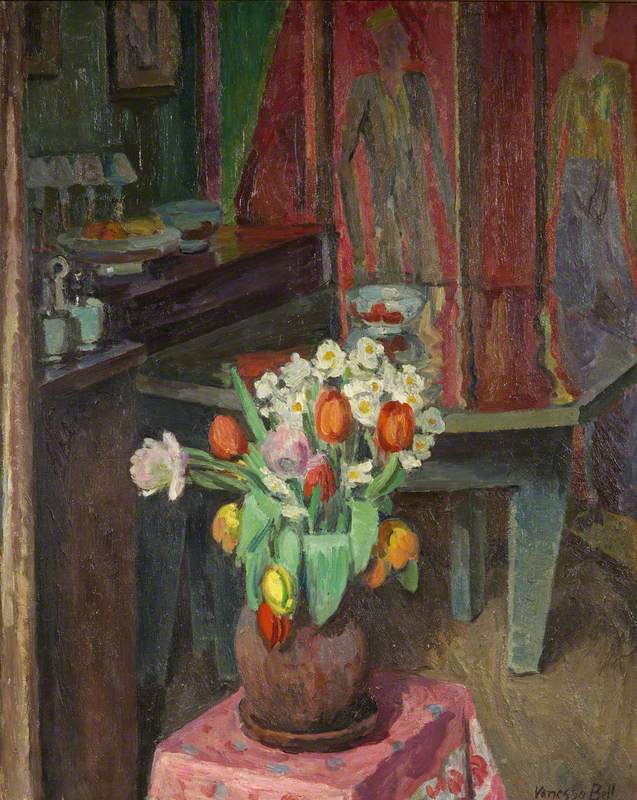

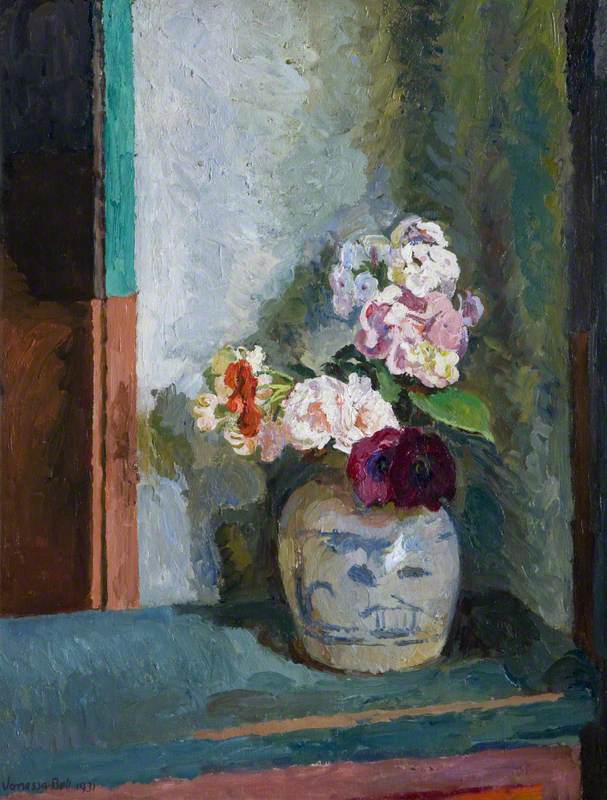

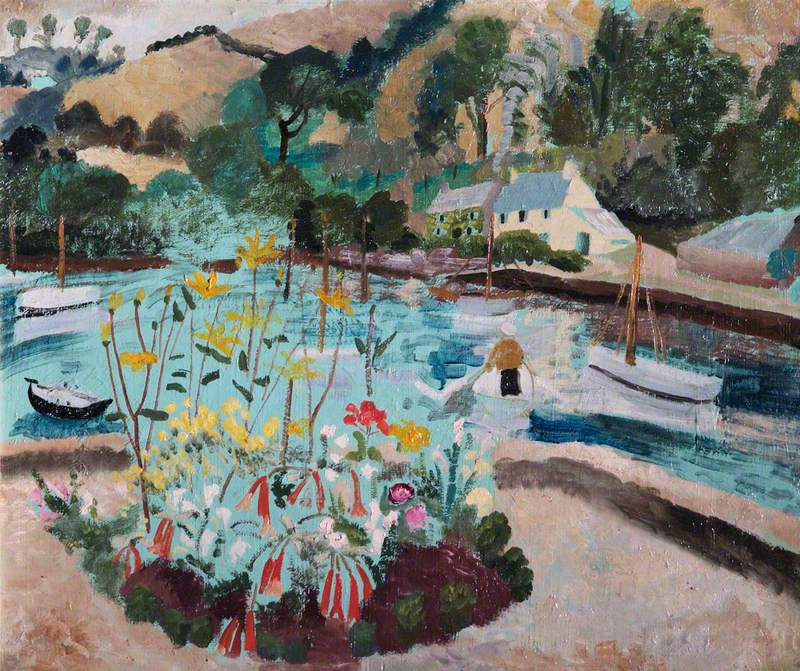

In the twentieth century, the opportunities available to female artists increased dramatically. They were no longer limited to the subject of flowers in their artwork and could freely explore other genres. Despite this freedom, flowers still held a fascination for many modern artists. Artists like Dod Procter and Vanessa Bell saw flowers as encapsulating the colours, forms, patterns, and shapes that were central to modern art.

Winifred Nicholson, in particular, considered flowers to be the perfect subject to encapsulate modern ideas about painting with their unruly bursts of colour and naturally abstract, uncontrollable geometry. Nicolson often depicted bunches of flowers in the foreground of her work, placing them on windowsills and tables, and using their colour to activate their surroundings, making the image sing. Nicholson once stated that 'I like painting flowers – I have tried to paint many things in many different ways, but my paintbrush always gives a tremor of pleasure when I let it paint a flower…'

Vanessa Bell painted a wide variety of subjects throughout her career, but it was through her flower painting that she made her public name and her income. Her works delight in everyday objects and interiors. Like Nicholson, Bell uses the flowers as a focal point through which to explore the boundary between the inside and outside world.

For some, however, flowers continued to be associated with the ideas of traditional femininity rooted in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and were not seen as a sufficiently modern subject. It is for this reason, some critics have argued, that the work of pioneering artists like Nicholson has only recently begun to be recognised as significant.

It is interesting to consider whether this thinking applies to works by Elizabeth Whitehead at Leamington. Her work Peonies was made in 1928 and its loose brushwork reflects her training at the Académie Julian at the turn of the century. However, perhaps the subject and composition were too traditional for it to gain greater recognition.

Flowers continue to inspire many contemporary female artists, through their dynamic colours and forms but also scientifically. Botanical illustration thrives in the modern day and interestingly is still a predominantly female field. Whilst the relationship between female artists and flowers has undoubtedly shifted over time, the long association between femininity and flowers continues.

Whilst many men have painted flowers throughout history, it has not been bound up with their gender. Floral art provides an excellent prism for understanding the experience of female artists over time, showing how women have cultivated their own opportunities, growing, and often outgrowing the limitations placed on them.

Jane Simpkiss, Fine Art Curator at Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum and co-curator of the exhibition

'Outgrowing: Flowers and female artists, 1700 to Now' is currently on at Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum until the 24th April 2022

!['Phoebe Boswell: A Tree Says [In These Boughs The World Rustles]' at Orleans House Gallery](https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/w800h800/artuk_stories/boswell753x1000-edited-thumb-1.jpg)